What they carried: Bay of Pigs Editon

Today is the 60th anniversary of the final counter-attack by Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces near Playa Girón, 19 April 1961– in which over 25,000 Cuban regulars backed up by at least twice as much armed militia and under definitive air cover– rolled up the remaining 1,300~ men of Brigada Asalto 2506, the Cuban exile unit armed and equipped by the U.S. government.

Speaking of which, the National Archives has a ton of interesting Bay of Pigs documents digitized online.

Rather than a low-key infiltration of small teams to set the countryside against Havanna, which may have succeeded, the CIA went all-in on an overly ambitious plan to seize and hold territory in an effort to give the anti-Castro movement a tangible slice of “Free Cuba.”

The documents include a list of small arms and munitions for the brigade detail a shopping list of WWII surplus gear: 485 M1 Garands (although some were seen with Johnson M1941 rifles), 150 M1 Carbines, 470 SMGs (mostly M3 Grease Guns although some Reisings were used as well), 465 pistols, 108 M1918 BAR light machine guns, 30 M1919 Browning .30 cal GPMGs, 44 .50 cal heavy machine guns, 75 M20 Super Bazookas (with 2,400 rockets), 18 57mm recoilless rifles, 3 75mm recoilless rifles, 36 60mm light mortars, 18 81mm mortars, 6 4.2-inch mortars (the brigade’s largest weapons), 5 76mm M5 anti-tank guns, as well as demo kits and lots of hand grenades (22,000). To feed this collection, just over 1 million cartridges were to be provided.

“Three members of Brigade 2506’s honor guard stand with their new unit flag while training at Trax Base before the Bay of Pigs invasion.” Note the WWII-era duck hunter camo and M1 Garands. Via a 2012 San Antionio Times article.

To provide support moving off the beach, five M41 Walker Bulldog light (23-ton) tanks were taken from U.S. Army stocks and provided to the brigadistas to form an armored platoon. Mounting 76mm guns, the M41s went on to go head-to-head with large numbers of Cuban T-34/85s and acquitted themselves fairly well despite the Soviet-made tanks’ heavier armor and larger gun.

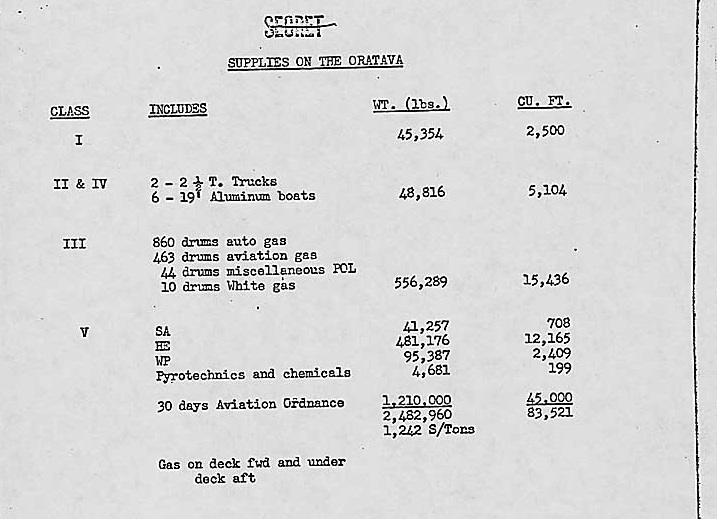

It was a pretty significant amount of gear, loaded on a “ghost fleet” of old LCIs and LCUs (some crewed by American MSTS mariners) as well as leased Garcia-line N-3 type liberty ships with the intention of landing the first 15 days worth of supplies with the initial wave, then returning with the second 15 days worth ASAP.

The initial load included 18,000 C-rations and 22 tons of bulk rations (rice, beans, dried meat et. al) as well as 54 19-foot aluminum skiffs with outboard motors and a range of LCVPs to be used as ship-to-shore connectors.

As Castro’s forces were able to retain air superiority via a handful of T-33 Shooting Stars, B-26 Invaders, and Hawker Sea Furies, the most crucial phase of the landings– keeping the men on the beach supplied and able to move inland– never had a chance.

SS Houston, an N-3 type cargo ship, was one of two sunk during the landing. She carried 183 tons of Brigade 2506’s equipment including its 50-bed field hospital.

Between April 17th and 20th, 10 Cuban pilots fly a total of just 70 missions for Castro’s forces, bringing down nine B-26 planes, and sinking two 5,000 ton freighters, one communication boat, three landing craft for transporting equipment, and five for troops. (“Playa Girón Primer Tomo, 114-115)

Some 25 miles over the horizon in International Waters, a U.S. Navy task force including the carriers Boxer and Essex, was ready to provide cover for the Cuban exiles but was ordered to stand down at the last minute. Their air wings could have made quick work of Castro’s air force, and hammered the lines around the beachhead with everything from 500-pound bombs to napalm, but it could have triggered a much larger conflict, possibly including Soviet intervention in Europe.

“For maritime historians, the Bay of Pigs invasion has become known as the world’s most disastrous amphibious operation,” notes Capt. James McNamara in Freightwaves.

Such an outcome was theorized in advance by an Air Force advisor, Lt. Col. B.W. Tarwater, who had given the idea of an amphibious assault against Cuban aviation assets as pretty low, urging that it should have been an airlift with adequate air support.

Trained for over 13 weeks by American advisors in Nicaragua and elsewhere, the top-level plan had been for Brigade 2506 to “go guerilla” if they received pushback from conventional forces that they could not defeat or found themselves cut off from the beaches. However, on the ground level, this was more wishful thinking than anything and such discussions had not filtered down to the rank-and-file.

“It was mutually agreed that these contingency plans would be discussed only down to the level of battalion commanders prior to landing to avoid defeatist talk and apprehension concerning the success of the operation,” reads a report from the time.

Locked into the beachhead with dwindling supplies under constant air and artillery attack, the brigadistas were wrapped up and nearly 1,200 were captured by the end of D+3.

Most were later repatriated to the U.S. after nearly two years in Cuban prisons, exchanged for millions in American aid.

As a good bookend to the event, Raul Castro recently confirmed he is stepping down as Cuba’s Communist party boss, ending the six-decade Castro-era in the country.

The Brigade 2506 Museum, maintained by the Bay of Pigs Veterans Association, has much more information for those who are curious.