Warship Wednesday, Aug. 24, 2022: Last Dance of the Prancing Dragon

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Aug. 24, 2022: Last Dance of the Prancing Dragon

Colorized photo by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

Above we see the Japanese light carrier Ryujo (also sometimes seen in the West incorrectly as Ryukyu) on sea trials at Satamisaki-oki, 6 September 1934 after her reconstruction, note her open bow and tall flight deck, showing off her bridge under the lip of the flattop. Built to a problematic design, she had lots of teething problems and, while she breathed fire in the Empire’s dramatic expansion after Pearl Harbor, the sea closed over her some 80 years ago today and extinguished her flames.

If you compare the development of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s aircraft carrier program in the 1920s and 30s to that of the U.S. Navy, there is a clear parallel. Each fleet had an initial, awkward, flattop commissioned in 1922 that proved to be a “schoolship” design to cradle a budding naval aviation program (Japan’s circa 1922 10,000-ton Hosho vs the 14,000-ton USS Langley). This was followed by a pair of much larger carriers that were built on the hulls of battlewagons whose construction had been canceled due to the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty but still carried large enough 7.9-inch/8-inch gun batteries to rate them as heavy cruisers in armament if not in armor (the 38,000/40,000-ton Kaga and Akagi vs. the 36,000-ton USS Lexington and USS Saratoga) that would pioneer the art of using such vessels via war gaming exercises. Then came smallish (to make the most of treaty limits), specially-designed, one-off carriers that were built after several years of experience with the type– the “under 10,000-ton” Ryujo vs the 15,000-ton USS Ranger (CV-4), which would be test beds for the bigger and better designs that each country would turn to for heavy lifting in 1942 (32,000-ton Shokaku class vs the 25,000-ton Yorktown class).

Laid down on 26 November 1929 at Mitsubishi in Yokoyama, Ryujo, whose name translates into something akin to “prancing dragon” or “dragon phoenix,” was slipped in by the Japanese as a nominal 8,000-ton aviation ship before the 1930 London Naval Treaty came in and limited even these small carriers as well as placed an armament cap of 6-inch guns on flattops.

Ryujo under construction Drydock No. 5, Yokosuka, Japan, 20 Oct 1931. Note how small she appears in the battleship-sized dock

Built on a slim 590-foot cruiser-style hull that, with a dozen boilers and a pair of steam turbines could make 29 knots, the Japanese elected for an extremely top-heavy build above the waterline placing her double-deck hangars and stubby 513-foot long flight deck towering some 50-feet into above the 01 deck to what proved to be an unsteady metacentric height (GM). Like Langley and Hosho, she was a true flattop, lacking a topside island, which would have made the whole thing even more unstable, instead opting to have a broad “greenhouse” bridge on the forward lip of the flight deck.

A period postcard of the Japanese aircraft carriers Ryūjō (top) and the legacy Hōshō. Note the height difference

Close-up view of the stern of carrier Ryujo, Yokosuka, Japan, 19 June 1933. Note how high her flight deck is from the main deck.

Ryujo Photograph taken in 1933, when the ship was first completed. The original print was provided by Dr. Oscar Parkes, Editor, Jane’s Fighting Ships. It was filed on 27 October 1933. NH 42271

She spent 1933 and 1935 in a series of rebuilds that moved to address her stability issues– which she suffered in a typhoon that left her hangar flooded. These changes included torpedo bulges and active stabilizers on her hull, more ballast, and, by a third rebuild completed in 1940, carried a redesigned bow form with re-ducted funnels.

Close-up of Japanese carrier Ryujo’s side mounted exhaust funnels and 12.7cm anti-aircraft guns, Yokosuka, 20 March 1933

This pushed her to over 12,700 tons in displacement and change her profile.

Aircraft carrier Ryujo undergoing full-scale trials after restoration performance improvement work (September 6, 1934, between the pillars at Satamisaki). Colorized photo by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

She saw her inaugural taste of combat in the war with China in the last quarter of 1937, operating a mix of a dozen Navy Type 95 Carrier Fighter and Type 94/96 Carrier Bombers (Susies), both highly maneuverable biplanes. Her Type 95s met Chinese KMT-flown Curtiss F11C Goshawks in aerial combat with the Japanese claiming six kills.

Ryujo at sea 1936. Colorized photo by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

It should be observed that the two 670-foot submarine tenders, Zuiho and Shoho, that were converted to light carriers in 1940-41, as well as the tender Taigei (converted and renamed Ryuho) and the three Nitta Maru-class cargo liners converted to Taiyō-class escort carriers in 1942-43, greatly favored our Ryujo in profile and they were surely constructed with the lessons gleaned from what had gone wrong with that latter carrier in the previous decade. Notably, while still having a flush deck design without an island, these six conversions only had a single hangar deck instead of Ryujo’s double hangar deck, giving them a smaller maximum air wing (25-30 aircraft vs 40-50) but a shorter height and thus better seakeeping ability.

Running Amok for five months

Ryujo would be left behind when Yamamoto sent Nagumo’s Kido Butai eight-carrier strike force (Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, Shokaku, Soryu, and Zuikaku on the attack itself, screened from a distance by Hosho and Zuiho) to hit Pearl Harbor, instead tasking the wallowing light carrier with being the sole flattop supporting Takahashi’s Third Fleet’s invasion of the Philippines.

With the Japanese keeping their battleships in a fighting reserve in the Home Islands for the anticipated Tsushima-style fleet action, and every other carrier either in the yard or on the Pearl Harbor operation, Ryujo was the Third Fleet’s only capital ship, a key asset operating amid a force of cruisers, seaplane tenders, and destroyers– appreciated at last!

Ryujo was still 100 percent more carrier than RADM Thomas Hart’s Asiatic Fleet had in their order of battle, and the dragon was very active in the PI with her airwing of Nakajima B5N “Kate” torpedo bombers and Mitsubishi A5M “Claude” fighters. It was her planes that delivered the first strikes of the Japanese invasion on 8 December when they hit U.S. Navy assets in Davao Bay in Northern Luzon then spent the rest of the month covering the landings there.

A Japanese Nakajima B5N1 Type 97 from the aircraft carrier Ryujo flies over the U.S. Navy seaplane tender USS William B. Preston (AVD-7) in Malalag Bay, Mindanao, Philippines, during the early morning of 8 December 1941. Two Consolidated PBY-4 Catalinas (101-P-4 and 101-P-7) from Patrol Squadron 01 (VP-101), Patrol Wing 10, are burning offshore. Via Maru magazine No. 461, December 1984 via j-aircraft.org

In January 1942, she was shifted south to support the Malaysia invasion from Japanese-occupied Camranh Bay in French Indochina, with her Claudes thought to have shot down at least two RAF Lockheed Hudsons off Redang Island while her Kates are credited with anti-shipping strikes off Singapore on 13-17 February that sent the Dutch tankers Merula (8,226 tons) and Manvantara (8,237 tons) along with the British steamer Subadar (5,424 tons), to the bottom. Fending off counterattacks, her Claudes shot down two RAF Bristol Blenheim from 84 Squadron and a Dornier Do 24 flying boat of the Dutch Navy.

Here we see Hr.Ms. Java was under attack by Japanese Nakajima B5N “Kate” high-altitude bombers from the light carrier Ryujo in the Gaspar Straits of what is today Indonesia, 15 February 1942. Remarkably, the Dutch light cruiser would come through this hail without a scratch, however, her days were numbered, and she would be on the bottom of the Pacific within a fortnight of the above image. Australian War Memorial photo 305183

While her Kates twice attacked Hr.Ms. Java and HMS Exeter (68) of Graf Spee fame on 15 February without causing either cruiser much damage, Ryujo’s air group found more success in attacking the Dutch destroyer Hr.Ms. Van Nes two days later. A strike of 10 B5N1s chased the Admiralen-class greyhound down in the Java Sea and landed two hits, sending her to the bottom with 68 of her crewmen.

Two Japanese Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers (B5N2 in the foreground and B5N1 in the background) over the Java Sea on 17 February 1942. The smoke in the background is coming from the Dutch destroyer Hr.Ms. Van Nes. She was sunk by Japanese aircraft from the aircraft carrier Ryujo circa 30 km from Toboali, Bangka Island while escorting the troop transport Sloet van Beele.

On the morning of 1 March in the immediate aftermath of the overnight Battle of the Java Sea, her Kates all but disabled the old Clemson-class four-piper USS Pope (DD-225) off Bawean Island, leaving her to be finished off by Japanese cruisers.

April saw Ryujo join Ozawa’s mobile force for the epic “Operation C” raids into the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal, where she split her time sending out Kates on search-shipping strikes (sinking the 5,082-ton British steamer Harpasa on 5 April) and raids on the Indian ports of Vizagapatam and Cocanada, accounting for eight assorted Allied ships on 6 April in conjunction with the guns of Ozawa’s cruisers. It is even reported by Combined Fleet that Ryujo was able to use her own 5-inch guns against surface targets as well, an almost unheard of level of sea control.

Arriving back home in Kure in May after five solid months of running amok, Ryujo would land her obsolete Claude fighters in favor of shiny new Mitsubishi Type 0 A6M2 “Zekes” of the latest design– some of which just left the factory– as the Admiralty aimed to send her into an operation where she may expect interference from American F4F Wildcats and P-39 Aircobra/P-40 Warhawks: Operation AL, the diversionary seizure of Attu and Kiska in the Aleutians during the Battle of Midway.

Dutch Harbor & Koga’s Zero

Sent to attack Alaska as part of VADM Hosogaya Boshiro’s Aleutian invasion force in company with the new 27,500-ton carrier Junyo, Ryujo would be active in a series of three air raids on Dutch Harbor and Unalaska on 3-4 June which didn’t cause much damage on either side, then covered the bloodless landings at Attu and Kiska on the 7th.

Dutch Harbor, Unalaska Island, Alaska, 3 June 1942: A Navy machine gun crew watches intently as Japanese aircraft depart the scene after the attack. Smoke in the background is from the steamer SS Northwestern, set ablaze by a dive bomber (80-G-11749).

However, one of the aircraft that failed to return to Ryujo was one of those beautiful new Zekes, SN 4593/Tail DI-108, flown by 19-year-old Flight Petty Officer Tadayoshi Koga. His oil line hit by a “magic BB” from small arms fire over Dutch Harbor, Koga tried to land his smoking fighter on remote green Akutan Island, some 25 miles from nowhere, where it could possibly be recovered and flown back home or destroyed in place if needed. However, it turned out that the flat field Koga aimed for on Akutan was a bog and his aircraft flipped, killing him, on contact.

Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero-sen 10 July 1942, on Akutan Island, in the Aleutians aircraft had been flown by petty officer Tadayoshi Koga, IJN, from the carrier RYUJO. Aircraft damaged on 4 June 1942; the pilot was killed when the plane flipped over on its back. This “Zero” was the first captured intact for flight tests. NH 82481

U.S. Navy personnel inspect Koga’s Zero. The petty officer’s body was recovered still inside the cockpit, relatively preserved by the icy bog despite being there for over a month. Regretfully, a number of images of his cadaver are digitized and in wide circulation. Museum of the Aleutians Collections. MOTA 2018.16.10

Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero-Sen on the docks at Dutch Harbor, Alaska, 17 July 1942. This plane, from carrier RYUJO, had crash landed after the Dutch Harbor Raid on 4 June 1942. It was salvaged by VP-41 and was the first “Zero” captured intact for flight tests. NH 91339

More on Koga’s plane later.

The Dragon’s final dance

Having returned to Kure in July after the disaster that befell the Japanese carrier force in a single day at Midway (“scratch four flattops”), Ryujo was now suddenly more important than she had ever been before.

By early August, she was attached to Nagumo’s Main Unit Mobile Force– who the Japanese somehow still trusted– alongside the large fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku of the First Carrier Division which had survived Midway by not being at Midway. Coupled with the battleships Hiei and Kirishima (which would never come back home), the force was dispatched towards Truk to challenge the growing American presence on Guadalcanal. With Shokaku and Zuikaku large enough to tote both strike and fighter packages, the smaller Ryujo, paired with the old battleship Mutsu in a diversionary force away from the two bigger carriers, would instead have a fighter-heavy air wing of 9 Kates and 24 Zekes as American flattops were known to be lurking in the area.

On 24 August, Nagumo’s carriers were close enough to attack Henderson Field on Guadalcanal but in turn fell under the crosshairs of the numerical inferior Task Force 61, commanded by VADM Frank J. Fletcher (who had spanked Nagumo 11 weeks earlier at Midway), in what went down in the history books as Battle of Eastern Solomons. While Ryujo’s strike would hit the U.S. positions on Lunga Point– in a raid observed by Fletcher’s radar-equipped force– SBDs from Bombing Three and TBFs from Torpedo Eight off USS Saratoga (CV 3) would find the relatively undefended Ryujo and leave her dead in the water where land-based B-17s would find her in two follow-on raids.

A U.S. Navy Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless flies over the aircraft carriers USS Enterprise (CV-6), foreground, and USS Saratoga (CV-3) near Guadalcanal. The aircraft is likely on anti-submarine patrol. Saratoga is trailed by her plane guard destroyer. Another flight of three aircraft is visible near Saratoga. The radar array on the Enterprise has been obscured by a wartime censor. U.S. Navy National Naval Aviation Museum photo NNAM.1996.253.671

Battle of the Eastern Solomons, 24 August 1942: The damaged and immobile Japanese aircraft carrier Ryujo was photographed from a USAAF B-17 bomber, during a high-level bombing attack on 24 August 1942. The destroyers Amatsukaze and Tokitsukaze had been removing her crew and are now underway, one from a bow-to-bow position and the other from alongside. Two “sticks” of bombs are bursting on the water, more than a ship length beyond the carrier. The bow of the cruiser Tone is visible at the extreme right. 80-G-88021

As detailed by Combined Fleet:

- 1357 RYUJO is attacked by enemy aircraft (30 SBD and 8 TBF launched at 1315 from USS SARATOGA, (CV-3). The CAP manages to shoot down one TBF, but the carrier receives four bomb hits, many near-misses, and one torpedo hit aft of amidships. The torpedo floods the starboard engine room, and the ship begins to list and lose speed. A second torpedo hit, or large bomb appears to have damaged the port bow.

- 1408, RYUJO turned north and attempted to retire as ordered by Admiral Yamamoto. But though the fire is extinguished, the list increased to 21 degrees, and flooding disabled the boilers and machinery.

- 1420 RYUJO stops. At 1515 ‘Abandon Ship’ is ordered. AMATSUKAZE draws close along the low starboard side to attempt to transfer the crew bodily to her by planks linking the ships.

- 1610-1625 During abandonment, the carrier and screen are bombed by B-17s that are engaged by her fighters, and she receives no further damage.

- 1730 B-17s bomb again but again no additional damage. AMATSUKAZE completes rescue, and shortly after, about:

- 1755 RYUJO capsized to starboard and after floating long enough to reveal holes in her bottom, sinks stern first at 06-10S, 160-50E, bearing 10 degrees 106 miles from Tulagi.

- Four aircraft go down with the ship. Seven officers – including XO Cdr (Captain posthumously) Kishi and Maintenance Officer LtCdr (Eng.) (Cdr (Eng.) posthumously) Nakagawa – and 113 petty officers and men are lost; Captain Kato and the survivors are rescued by destroyers AMATSUKAZE and TOKITSUKAZE and heavy cruiser TONE. The destroyers soon transfer these survivors to the TOEI MARU and TOHO MARU.

Epilogue

While Ryujo has been at the bottom of the Southern Pacific for 80 years now, her legacy should not be forgotten. When it comes to Koga’s advanced model Zero, left behind in Alaska in what was described as “98 percent condition,” the aircraft was so key to Allied intelligence efforts that it has been described as “The Fighter That Changed World War II.”

The folks over at Grumman were able to get their test pilots and engineers in it, then use lessons drawn from it to tweak the F6F Hellcat and later, the F7F and F8F.

As noted by Wings of the Rising Sun excerpts at The Aviation Geek Club:

Once the fighter had been sent to NAS Anacostia in late 1942, a series of test flights were performed by the Naval Air Station’s Flight Test Director, Cdr Frederick M. Trapnell. He flew identical flight profiles in both the Zero and U.S. fighters to compare their performance, executing similar aerial maneuvers in mock dogfights. U.S. Navy test pilot LT Melvin C. “Boogey” Hoffman was also checked out in the A6M2, after which he helped train Naval Aviators flying new F6F Hellcats, F4U Corsairs, and FM Wildcats by dogfighting with them in the Zero.

In 1943 the aircraft was evaluated in NACA’s LMAL in Hampton, Virginia, where the facility’s Full-Scale Wind Tunnel was used to evaluate the Zero’s aerodynamic qualities. It was also shown off to the public at Washington National Airport that same year during a war booty exhibition. By September 1944, the well-used A6M2 was stationed at NAS North Island once again, where it served as a training aid for “green” Naval Aviators preparing for duty in the Pacific.

RADM William N. Leonard said of Koga’s plane, “The captured Zero was a treasure. To my knowledge, no other captured machine has ever unlocked so many secrets at a time when the need was so great.” On the other side of the pond, Japanese Lt-Gen. Masatake Okumiya said the plane’s loss “was no less serious” than the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Midway, and “did much to hasten Japan’s final defeat.”

PO Koga, the teenage son of a carpenter, was at first buried in the hummocks some 100 yards from his crash site after he was extracted from the Zero. Exhumed in 1947, his remains were interred in the cemetery on Adak, in grave 1082 marked as “Japanese Flyer Killed in Action.” He was exhumed a final time in 1953 for repatriation along with 253 others from the Aleutians, and since then has been in the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Japan. The location of his lonely crash on Atukan, half a mile inland from Broad Bight, is occasionally visited by groups from Japan.

While Koga’s Zero was mauled in a mishap on the ground in February 1945 and then later scrapped, instruments from it are on display at the Museum of the U.S. Navy and two of its manufacturer’s plates are in the Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum in Anchorage, some of the only relics of Ryujo left.

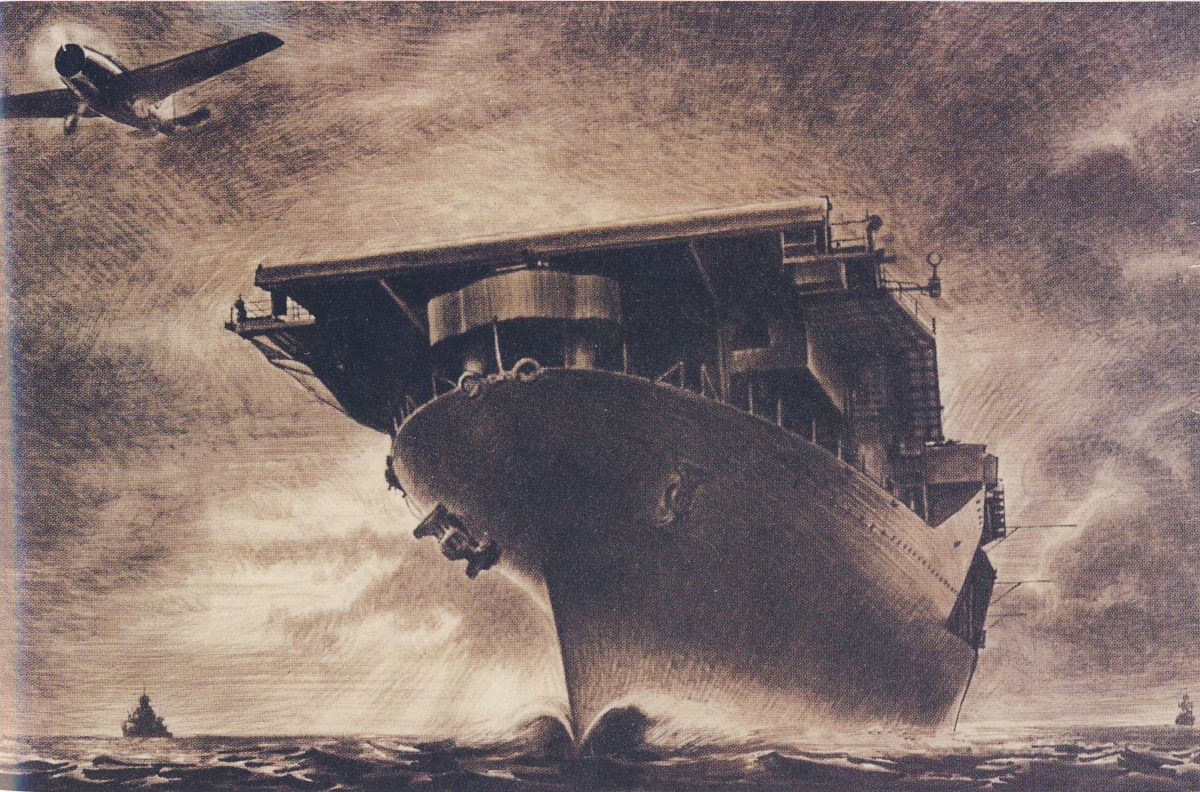

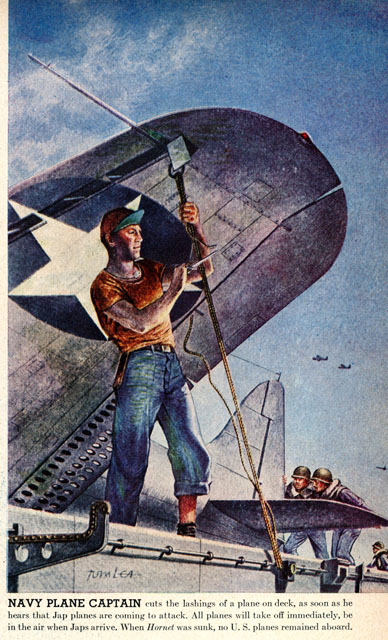

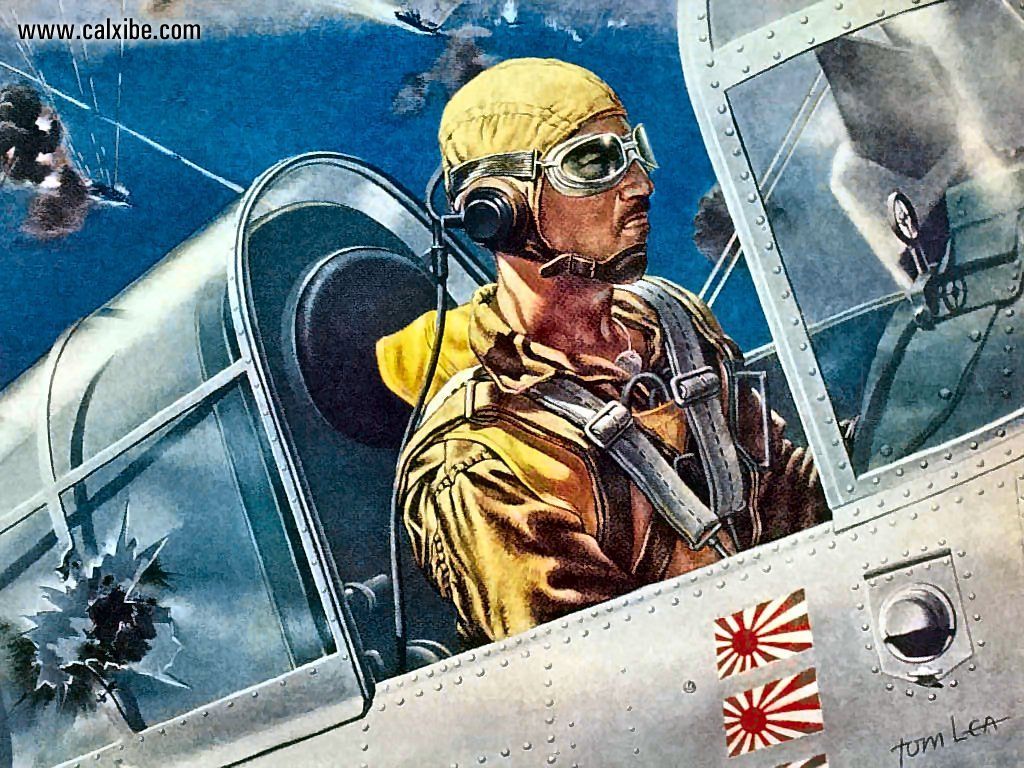

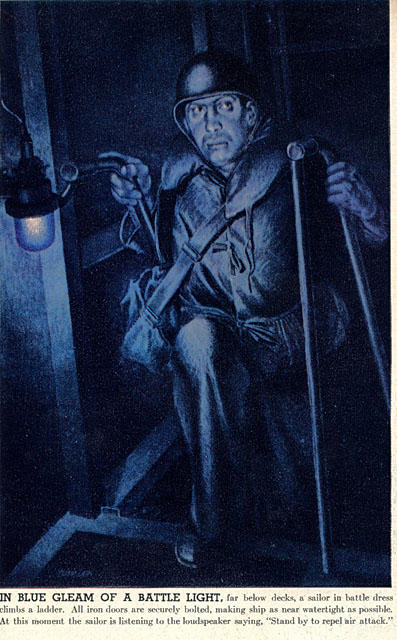

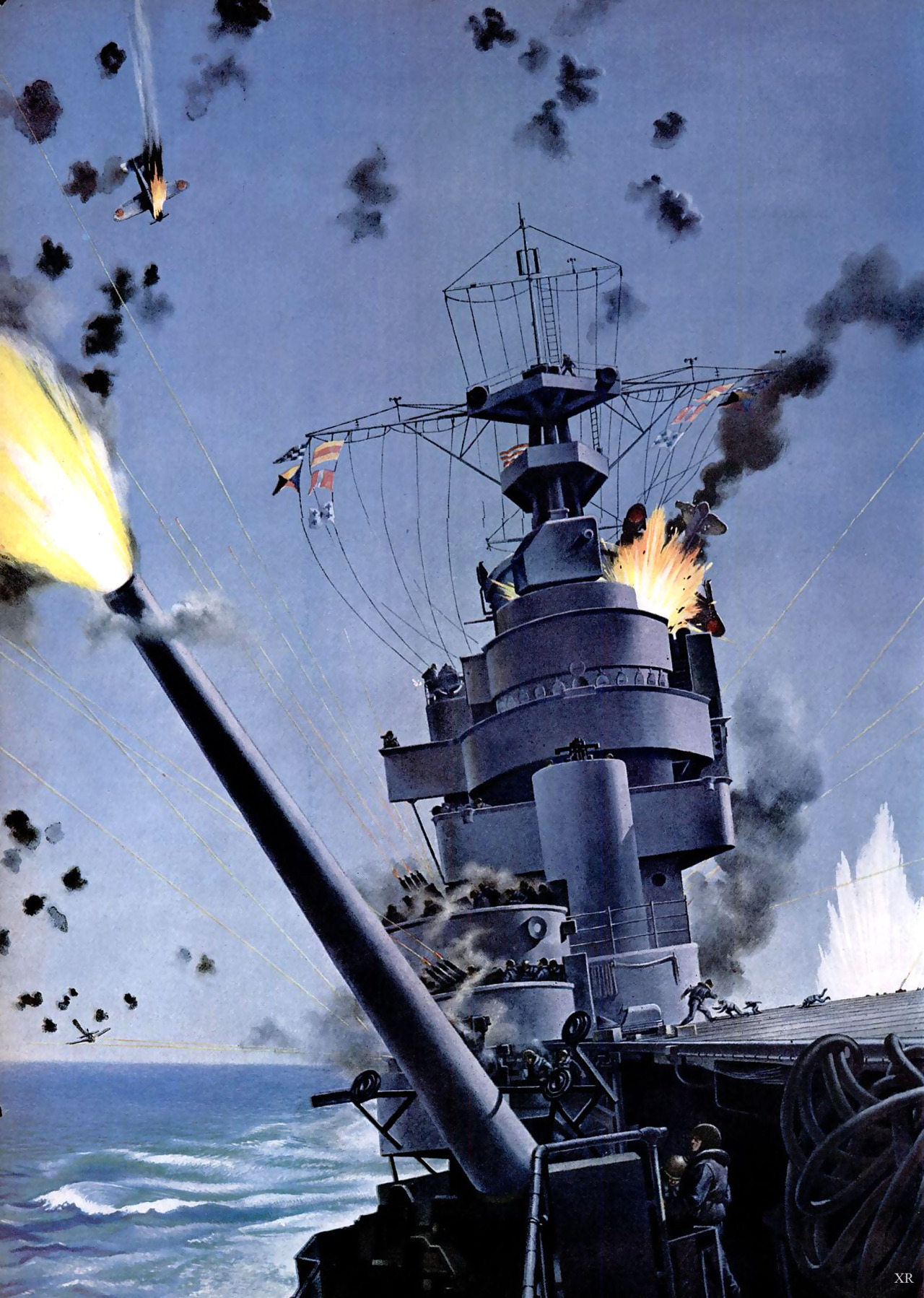

Ryujo is remembered in a variety of maritime art, most of which is used for scale model box art.

Specs:

(1941)

Displacement: 12,732 tons

Length: 590’7″

Beam: 68’2″

Draft: 23’3″

Machinery: 12 x Kampon water-tube boilers, 2 geared steam turbines, 2 shafts, 65,000 shp

Speed: 29 knots

Crew: 924

Airwing: up to 48 single-engine aircraft

Armament:

8 x 5″/40 Type 89 naval gun

4 x 25mm/60 Hotchkiss-licensed Type 96 light AA guns

24 x 13mm/76 AAAs

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.