Warship Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2022: Long Lance in the Night

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Feb. 16, 2022: Long Lance in the Night

Here we see Hr.Ms. Java was under attack by Japanese Nakajima B5N “Kate” high altitude bombers from the light carrier Ryujo in the Gaspar Straits of what is today Indonesia, some 80 years ago this week, 15 February 1942. Remarkably, the Dutch light cruiser would come through this hail without a scratch, however, her days were numbered, and she would be on the bottom of the Pacific within a fortnight of the above image.

Designed by Germaniawerft in Kiel on the cusp of the Great War, the three planned Java class cruisers were to meet the threat posed by the new Chikuma-class protected cruisers (5,000-tons, 440 ft oal, 8x 6″/45, 26 knots) of the Japanese Navy.

The response, originally an update of the German Navy’s Karlsruhe class, was a 6,670-ton (full load) 509.5-foot cruiser that could make 30+ knots on a trio of Krupp-Germania steam turbines fed by eight oil-fired Schulz-Thornycroft boilers (keep in mind one of the largest oil fields in the world was in the Dutch East Indies). Using 18 watertight bulkheads, they were fairly well protected for a circa 1913 cruiser design carrying a 3-inch belt, 4-inches on the gun shields, and 5-inches of Krupp armor on the conning tower.

Jane’s 1931 entry on the class, noting that “The German design of these ships is evident in their appearance.”

Their main battery consisted of ten Mark 6 5.9-inch/50 cal guns made by Bofors in Sweden, mounted in ten single mounts, two forward, two aft, and three along each center beam, giving the cruisers a seven-gun broadside.

Unless noted, all images are from the Dutch Fotoafdrukken Koninklijke Marine collection via the NIMH, which has a ton of photos digitized.

The 5.9/50 Bofors mounts had a decent 29-degree elevation for their period, used electric hoists, and a well-trained crew could fire five 101-pound shells per minute per mount, giving the Java class a theoretical rate of fire of 50 5.9-inch shells every 60 seconds. Holland would go on to use the same guns on the Flores and Johan Maurits van Nassau-class gunboats.

The 5.9/50s used an advanced fire control system with three large 4m rangefinders that made them exactly accurate in bombarding shore targets.

Night firing on Java. These ships carried six 47-inch searchlights and the Dutch trained extensively in fighting at night.

The cruisers’ secondary armament consisted of four 13-pounder 3″/55 Bofors/Wilton-Fijenoord Mark 4 AAA guns, one on either side of each mast, directed by a dedicated 2m AA rangefinder. While– unusually for a cruiser type in the first half of the 20th century– they did not carry torpedo tubes, the Java-class vessels did have weight and space available for 48 sea mines (12 in a belowdecks hold, 36 on deck tracks), defensive weapons that the Dutch were very fond of.

Designed to carry and support two floatplanes, the class originally used British Fairey IIIFs then switched to Fokker C. VIIWs and Fokker C. XIWs by 1939.

While the Dutch planned three of these cruisers– named after three Dutch East Indies islands (Java, Sumatra, and Celebes) — the Great War intervened and construction slowed, with the first two laid down in 1916 and Celebes in 1917, they languished and were redesigned with the knowledge gleaned from WWI naval lessons. Celebes would be canceled and only the first two vessels would see completion.

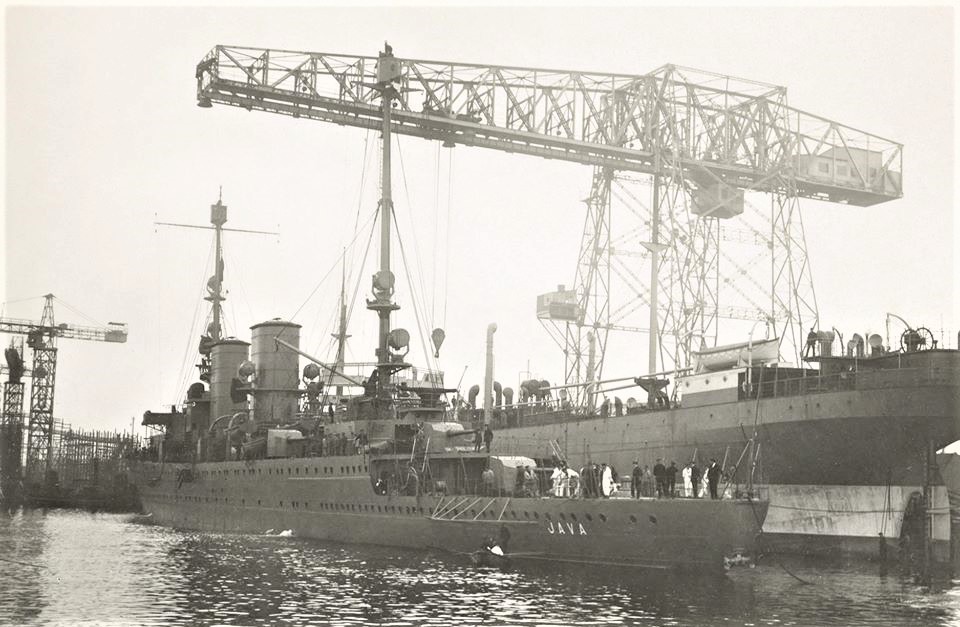

Java— ironically laid down at Koninklijke Maatschappij de Schelde (today Damen) in Flushing on 31 May 1916, the first day of the Battle of Jutland– would not be launched until 1921 and would spend the next four years fitting out.

The crew of Java in Amsterdam, 1925, complete with European wool uniforms. Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana of the royal family visit the ship. Sitting from left to right are: Commander M.J. Verloop (aide-de-camp of Queen Wilhelmina?), Captain L.J. Quant (commanding officer of Java), Queen Wilhelmina, Princess Juliana, Vice-Admiral C. Fock (Commanding Officer of Den Helder naval base), and Acting Vice-Admiral F. Bauduin (retired, aide-de-camp “in special service” of Queen Wilhelmina). Standing behind Captain Quant and Queen Wilhelmina is (then) Lieutenant-Commander J.Th. Furstner, executive officer and/or gunnery officer. (Collection Robert de Rooij)

A happy peace

Making 31.5-knots on her trials, Java commissioned 1 May 1925 and sailed for Asia by the end of the year. Her sistership Sumatra, built at NSM in Amsterdam, would join her in 1926.

The two sisters would spend the next decade cruising around the Pacific, calling at Japan and Australia, Hawaii, and China, showing the Dutch flag from San Francisco to Saigon to Singapore. Interestingly, she took place in the International Fleet Review at Yokohama to celebrate the coronation of Japan’s Showa emperor, Hirohito, in 1928.

In a practice shared by the Royal Navy and U.S. fleet in the same waters, the crew of the Dutch cruisers over these years took on a very local flavor, with many lower rates being filled by recruits drawn heavily from the islands’ Christian Manadonese and Ambonese minorities.

The Bataviasche Yacht Club in Tandjong Priok, Batavia. Fishing prahu under sail in the harbor of Tandjong Priok. In the background the cruiser Hr.Ms. Java. Remembrance book of the Bataviasche Yacht Club, Tandjong Priok, presented to its patron, VADM A.F. Gooszen, October 19, 1927.

S1c (Matroos 1e Klasse) J.G. Rozendal and friends of cruiser Hr.Ms. Java during an amphibious landing (Amfibische operaties) exercises with the ship’s landing division (landingsdivisie) at Madoera, 1927. Note the anchor on their cartridge belts, infantry uniforms with puttees and naval straw caps, and 6.5x53mm Geweer M. 95 Dutch Mannlichers. A really great study.

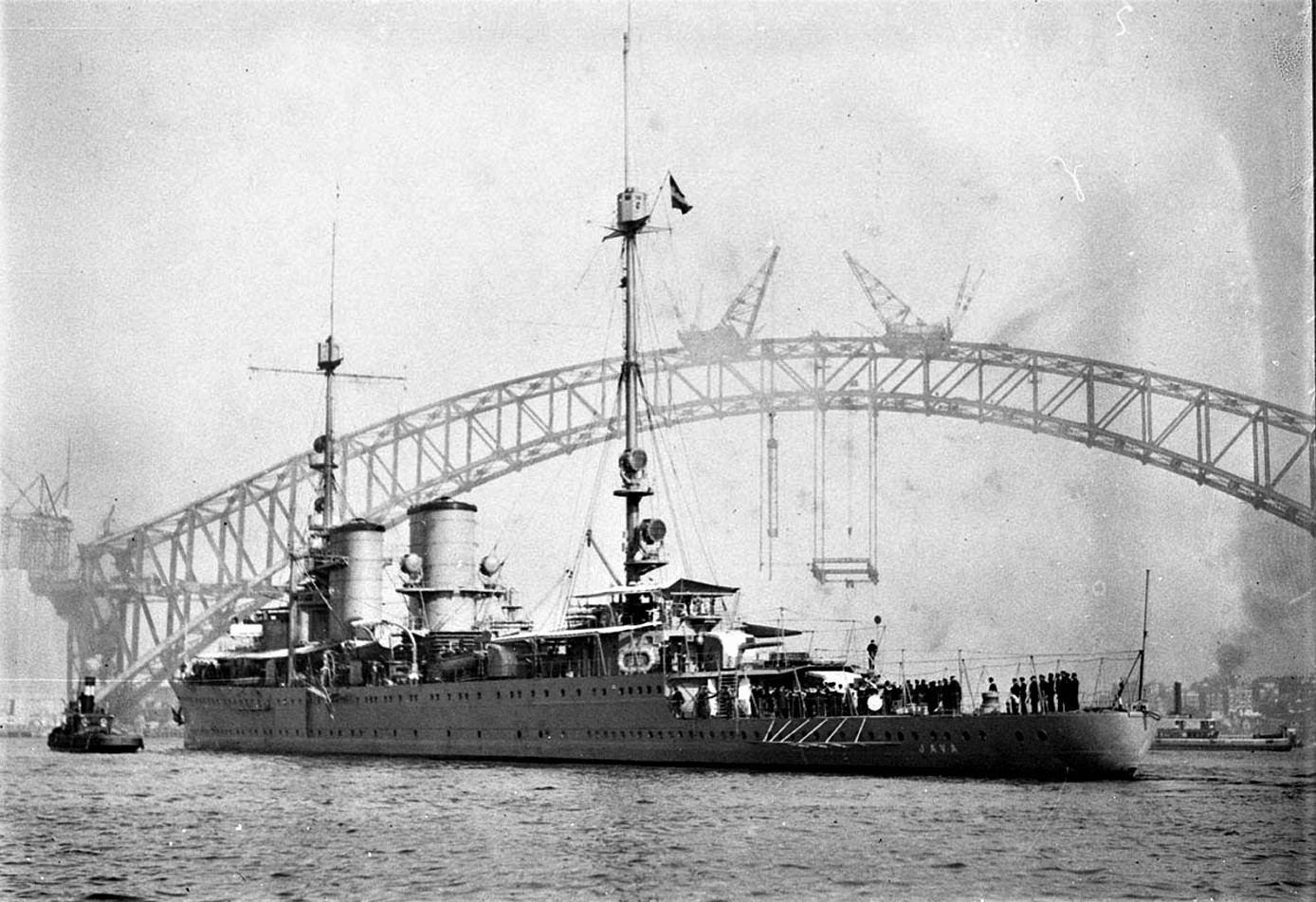

The Koninklijke Marine East Indies Squadron including Java and the destroyers De Ruyter and Eversten arrived in Sydney on 3 October 1930 and remained there for a week. The ships berthed at the Oceanic Steamship Company wharf and Burns Philp & Company Wharf in West Circular Quay. The Sydney Morning Herald reported on the “unfamiliar spectacle” of the Dutch squadron’s arrival.

Night scene with HNLMS Java berthed at West Circular Quay wharf, October 1930. Eversten is tied up next to her. Samuel J. Hood Studio Collection. Australian National Maritime Museum Object no. 00034761.

Dutch light cruiser Hr.Ms Java, Sydney, Octo 1930. Note the 5.9-inch gun with the sub-caliber spotting gun on the barrel. The individuals are the Dutch Consul and his wife along with RADM CC Kayser. Australian National Maritime Museum.

Dutch cruiser HNLMS Java, berthing with the unfinished Sydney Harbour Bridge as a background, circa 1930

Java Tandjong Priok, Batavia, Java, Nederlands-Indië 8.31.32. Note she is still in her original scheme with tall masts and more rounded funnel caps.

Hr.Ms. Java Dutch cruiser before reconstruction. Colorized photo by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

During the early 1930s, both Java and Sumatra were slowly refitted in Surabaya, a move that upgraded the engineering suite, deleted the deck mine racks and saw the old manually-loaded 3″/55 Bofors quartet landed, the latter replaced by a half-dozen automatic 40mm Vickers Maxim QF 2-pounders on pedestal mounts in a Luchtdoelbatterij.

Water-cooled and fed via 25-round cloth belts, the guns had been designed in 1915 as balloon-busters and could fire 50-75 rounds per minute.

With problems in Europe and the Dutch home fleet being cruiser poor– only able to count on the new 7,700-ton HNLMS De Ruyter still essentially on shakedown while a pair of Tromp-class “flotilla leaders” were still under construction– Java and Sumatra were recalled home to flex the country’s muscles in the waters off Spain during the early and most hectic days of the Spanish Civil War, clocking in there for much of 1936-37.

They also took a sideshow to Spithead for the fleet review there.

By 1938, Java was modernized at the Naval Dockyard in Den Helder. This dropped her Vickers balloon guns for four twin 40/56 Bofors No.3 guns, soon to be famous in U.S. Navy service, as well as six .50 cal water-cooled Browning model machine guns. Also added was a Hazemeyer (Thales) fire control set of the type later adopted by the USN, coupled with stabilized mounts for the Bofors, a deadly combination.

Talk about an epic photo, check out these Bofors 40mm gunners aboard Java, circa 1938. Note the shades.

With Franco in solid control of Spain and tensions with the Japanese heating up, our two Dutch cruisers returned to Indonesian waters, with the new De Ruyter accompanying them, while the Admiralty ordered two immense 12,000-ton De Zeven Provinciën-class cruisers laid down (that would not be completed until 1953.)

Kruiser Hr.Ms. Java manning rails coming into Soerabaja, returning from her two-year trip back to Holland

War!

De kruiser Hr.Ms. Java in Nederlands-Indië. at anchor after her major reconstruction. Note she has shorter masts and additional AAA batteries, among some of the most modern in the world at the time.

Of note, U-Boat.net has a great detailed account of Java’s war service.

When Hiter marched into Poland in September 1939, most of Europe broke out in war, but Holland, who had remained a staunch neutral during that conflict and still hosted deposed Kaiser Wilhelm in quiet exile, reaffirmed its neutrality in the new clash as well. However, that was not to be in the cards and, once the Germans marched into the Netherlands on 10 May 1940– the same day they crossed into Luxembourg and Belgium in a sweep through the Low Countries and into Northern France, the Dutch were in a major European war for the first time since Napolean was sent to St. Helena, whether they wanted it or not.

At that, Java dispatched boarding parties to capture the German Hapag-freighters Bitterfeld (7659 gt), Wuppertal (6737 gt), and Rhineland (6622 gt), which had been hiding from French and British warships in neutral Dutch East Indies waters at Padang.

Post-modernized Kruiser Hr.Ms. Java with Fokkers overhead. The Dutch Navy had 23 Fokker CXIV-W floatplanes in the Pacific in 1941

Cooperating with the British and Australians, Java was engaged in a series of convoys between the Dutch islands, Fiji, Singapore, and Brisbane, briefly mobilizing to keep an eye peeled in the summer of 1941 for the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer, which was incorrectly thought to be in the Indian Ocean headed for the Pacific.

One interesting interaction Java had in this period was to escort the Dutch transport ship Jagersfontein to Burma, which was carrying members of the American Volunteer Group, Claire Chennault’s soon-to-be-famous Flying Tigers.

While working with the Allies, a U.S. Navy spotter plane captured some of the best, last, images of the Dutch man-o-war.

Java (Dutch Light Cruiser, 1921) Aerial view from astern of the starboard side, August 1941. NH 80906

Once the Japanese started to push into the Dutch colony, simultaneously with the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and the Philippines, Java found herself in a whole new shooting war.

Escorting troopship Convoy BM 12 from Bombay to Singapore from 23 January to 4 February 1942, Java then joined an Allied task force under the command of Dutch RADM Karl W.F.M. Doorman consisting of the cruiser De Ruyter (Doorman’s flagship), the new destroyer leader Tromp, the British heavy cruiser HMS Exeter, the Australian light cruiser HMAS Hobart, and ten American and Dutch destroyers. The mission, from 14 February: a hit and run raid to the north of the Gaspar Straits to attack a reported Japanese convoy.

As shown in the first image of this post, the little surface action group was subjected to repeated Japanese air attacks in five waves, and in the predawn hours of 15 February, the Dutch destroyer HrMs Van Ghent ripped her hull out on a reef, dooming the vessel. Cutting their losses, Doorman split up his group, sending half to Batavia and half to Ratai Bay to refuel.

Four days later, essentially the same force, augmented by a flotilla of Dutch motor torpedo boats and two submarines, were thrown by Doorman into the mouth of the Japanese invasion fleet on the night of 19/20 February 1942 in the Badoeng Strait on the south-east coast of Bali. The outnumbered Japanese force, however, excelled in night combat tactics and were armed with the Long Lance torpedo, a fact that left Doorman’s fleet down another destroyer (HrMs Piet Hein) and the Tromp badly mauled and sent to Sydney for emergency repairs.

Then, on 27 February, Doorman’s Allied ABDACOM force, reinforced with the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth and the heavy cruiser USS Houston, sailed from Surabaya to challenge the Japanese invasion fleet in the Java Sea.

While that immense nightmare is beyond the scope of this piece, Java and De Ruyter‘s portion of it, as related in the 1943 U.S. Navy Combat Narrative of the Java Sea Campaign, is below:

Immediately after the loss of the (destroyer) Jupiter our striking force turned north. At 2217 it again passed the spot where the Kortenaer had gone down that afternoon, and survivors of the Dutch destroyer saw our cruisers foam past at high speed. Encounter was ordered to stop and picked up 113 men of the Kortenaer’s crew of 153. It was at first intended to take them to Batavia, but upon learning of a strong Japanese force to the west the captain returned to Surabaya.

The cruisers of our striking force were now left without any destroyer protection whatever. This dangerous situation was aggravated by the fact that enemy planes continued to light their course with flares. But Admiral Doorman’s orders were, “You must continue attacks until the enemy is destroyed,” and he pressed on north with a grim determination to reach the enemy convoy.

It is doubtful if he ever knew how close he did come to reaching it in this last magnificent attempt. The convoy had in fact remained in the area west or southwest of Bawean. At 1850 a PBY from Patrol Wing TEN had taken off to shadow it in the bright moonlight. At 1955 this plane saw star shells above 3 cruisers and 8 destroyers on a northerly course about 30 miles southwest of Bawean. As these appeared to be our own striking force no contact report was made.69 At 2235 our PBY found the convoy southwest of Bawean. Twenty-eight ships were counted in two groups, escorted by a cruiser and a destroyer. At this moment Admiral Doorman was headed toward this very spot, but it is doubtful if he ever received our plane’s report. It reached the Commander of the Naval Forces at Soerabaja at 2352, after which it was sent on to the commander of our striking force; but by that time both the De Ruyter and Java were already beneath the waters of the Java Sea. At 2315 the De Ruyter signaled, “Target at port four points.” In that direction were seen two cruisers which opened fire from a distance of about 9,000 yards. Perth replied with two or three salvos which landed on one of the enemy cruisers for several hits. The Japanese thereupon fired star shells which exploded between their ships and ours so that we could no longer see them.

Shortly afterward the De Ruyter received a hit aft and turned to starboard away from the enemy, followed by our other cruisers. As the Java, which had not been under enemy fire, turned to follow there was a tremendous explosion aft, evidently caused by a torpedo coming from port. Within a few seconds the whole after part of the ship was enveloped in flames.

The De Ruyter had continued her turn onto a southeasterly course when, very closely after the Java, she too was caught by a torpedo. United States Signalman Sholar, who was on board and was subsequently rescued, reported having seen a torpedo track on relative bearing 135°. There was an extraordinarily heavy explosion followed by fire. Perth, behind the flagship, swung sharply to the left to avoid a collision, while the Houston turned out of column to starboard. The crew of the De Ruyter assembled forward, as the after part of the ship up to the catapult was in flames. In a moment, the 40-mm. ammunition began to explode, causing many casualties, and the ship had to be abandoned. She sank within a few minutes. For some time, her foremast structure remained above the water, until a heavy explosion took the ship completely out of sight.70

The torpedoes which sank the two Dutch cruisers apparently came from the direction of the enemy cruisers and were probably fired by them. Both Sendai and Nati class cruisers are equipped with eight torpedo tubes.

Of our entire striking force, only the Houston and Perth now remained. They had expended most of their ammunition and were still followed by enemy aircraft. There seemed no possibility of reaching the enemy convoy, and about 0100 (February 28th) the two cruisers set course for Tandjong Priok in accordance with the original plan for retirement after the battle. On the way Perth informed Admiral Koenraad at Soerabaja of their destination and reported that the De Ruyter and Java had been disabled by heavy explosions at latitude 06°00′ S., longitude 112°00′ E.71 The hospital ship Op ten Noort was immediately dispatched toward the scene of their loss, but it is doubtful if she ever reached it. Sometime later Admiral Helfrich lost radio contact with the ship, and a plane reported seeing her in the custody of two Japanese destroyers.

Epilogue

The post-war analysis is certain that Java was struck by a Long Lance torpedo fired from the Japanese cruiser Nachi. The torpedo detonated an aft magazine and blew the stern off the ship, sending her to the bottom in 15 minutes with 512 of her crew. The Japanese captured 16 survivors.

Nachi would be destroyed by U.S. Navy carrier aircraft in the Philippines in 1944, avenging Java’s loss.

Japanese cruiser Nachi dead in the water after air attacks in Manila Bay, 5 November 1944. Taken by a USS Lexington plane. National Archives photograph, 80-G-288866. Note, Nachi also took part in the Battle of the Java Sea and played a major role in sinking the Dutch light cruiser Java.

Sistership Sumatra, who had escaped Java Sea as she was under refit in Ceylon, was later sent to the ETO and, in poor shape, was sunk as a blockship off Normandy in June 1944, her guns recycled to other Dutch ships.

In December 2002, a group from the MV Empress, searching for the wreck of HMS Exeter, found that of Java and De Ruyter, with the former at a depth of 69 meters on her starboard side. Shortly afterward, the looted ship’s bell surfaced for sale in Indonesia. It was later obtained by the Dutch government and is now on display in the National Military Museum in Soesterberg.

The names of the 915 Dutch sailors and marines killed at the Battle of the Java Sea at installed at the Kembang Kuning, the Dutch Memorial Cemetery in Surabaya, Indonesia, while in Holland the Dutch Naval Museum has a similar memorial that includes the recovered bell from De Ruyter and other artifacts.

In 2016, the Dutch government reported that the hulks of both Java and De Ruyter had been illegally salvaged to the point that the war graves had virtually ceased to exist.

Now more than ever, the expression “On a sailor’s grave, there are no roses blooming (Auf einem Seemannsgrab, da blühen keine Rosen)” remains valid.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!

Fascinating stuff. I’m very glad I found your site. Thanks, Christopher.

It would seem the Dutch fellow who captioned the photograph “Kruiser Hr.Ms. Java met een Dornier Do-24K maritieme patrouillevliegboot op de voorgrond” wasn’t wearing his glasses when he did so. The flying boat in the foreground is not a Dornier Do-24, but rather a Dornier Do-J Wal, Do-24s “grandfather”, so to speak, and predecessor in the Netherlands Naval Aviation Service (Marineluchtvaartdienst-MLD). Judging by the presence of the 75 mm/55 cal. Bofors/Wilton-Fijenoord Mark 4 AA guns and the awnings, the photograph must have been taken in the Dutch East Indies at some point between 1926, when the Do-J was introduced in MLD service, and the refit in the early 1930s that saw the removal of said AA guns, a few years before the first flight of the prototype of Do-24 (which, it must be pointed out, was developed to meet a requirement by the MLD).

Pingback: The German Flying Boats Busting Japanese Tin Cans | laststandonzombieisland

Pingback: Warship Wednesday, March 2, 2022: Burnt Java | laststandonzombieisland

Pingback: 95 Years Ago: Jan Hollander on the Szechnen Road | laststandonzombieisland

Pingback: Warship Wednesday, Aug. 24, 2022: Last Dance of the Prancing Dragon | laststandonzombieisland

Pingback: Warship Wednesday, Aug. 31, 2022: The Well-Traveled Admiral | laststandonzombieisland