Warship Wednesday, Aug. 16, 2023: Copenhagen’s Finest

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Aug. 16, 2023: Copenhagen’s Finest

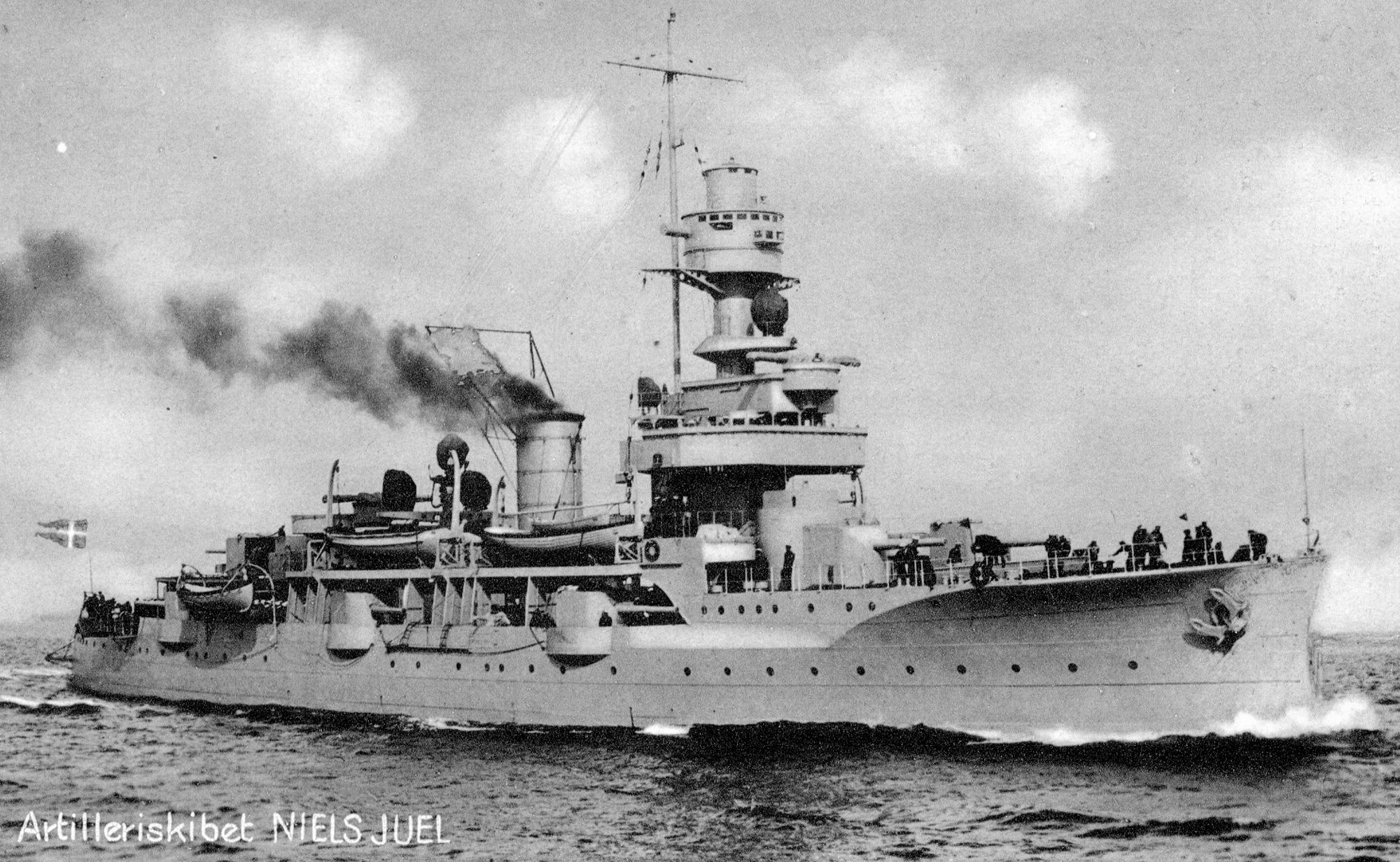

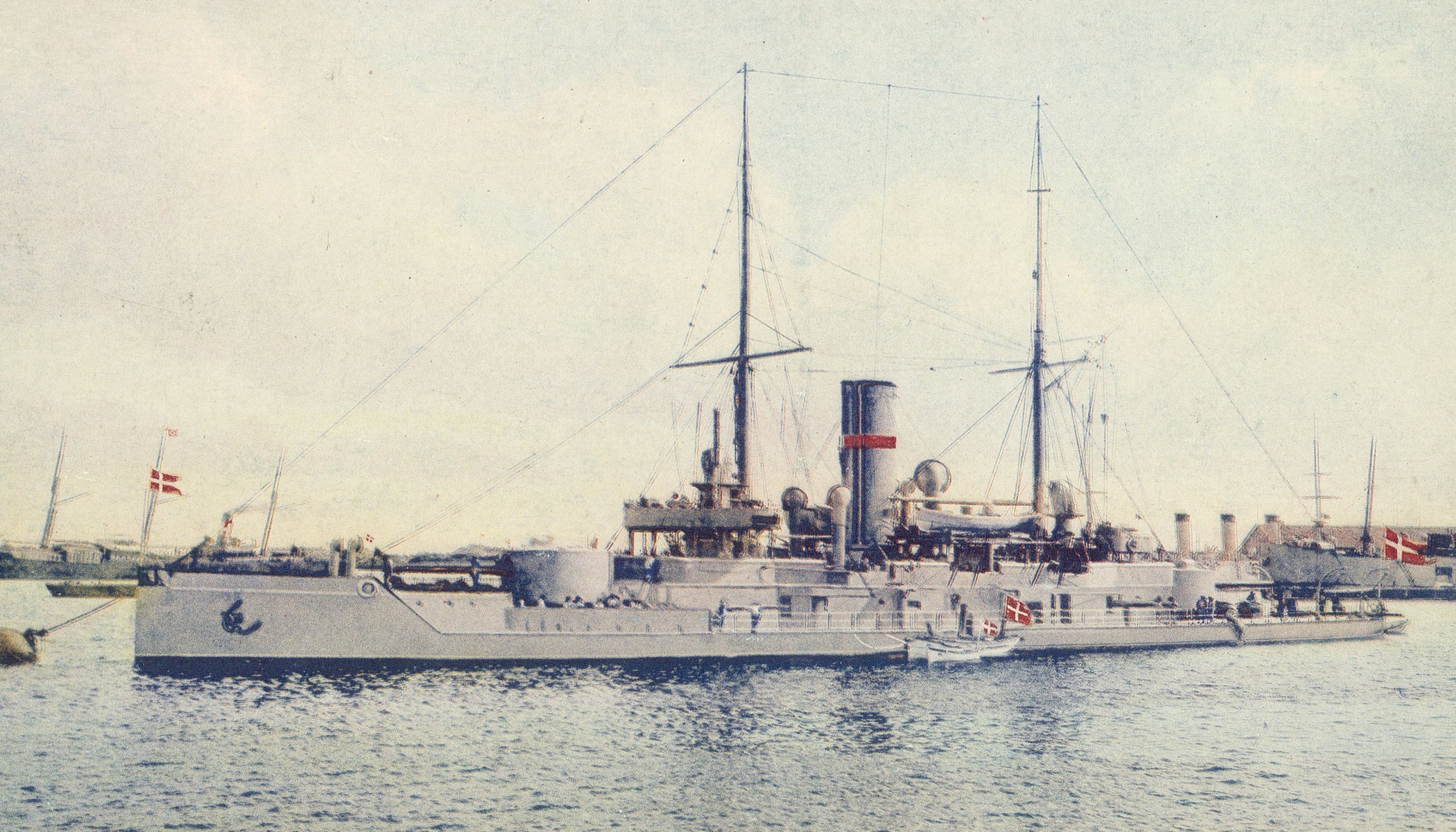

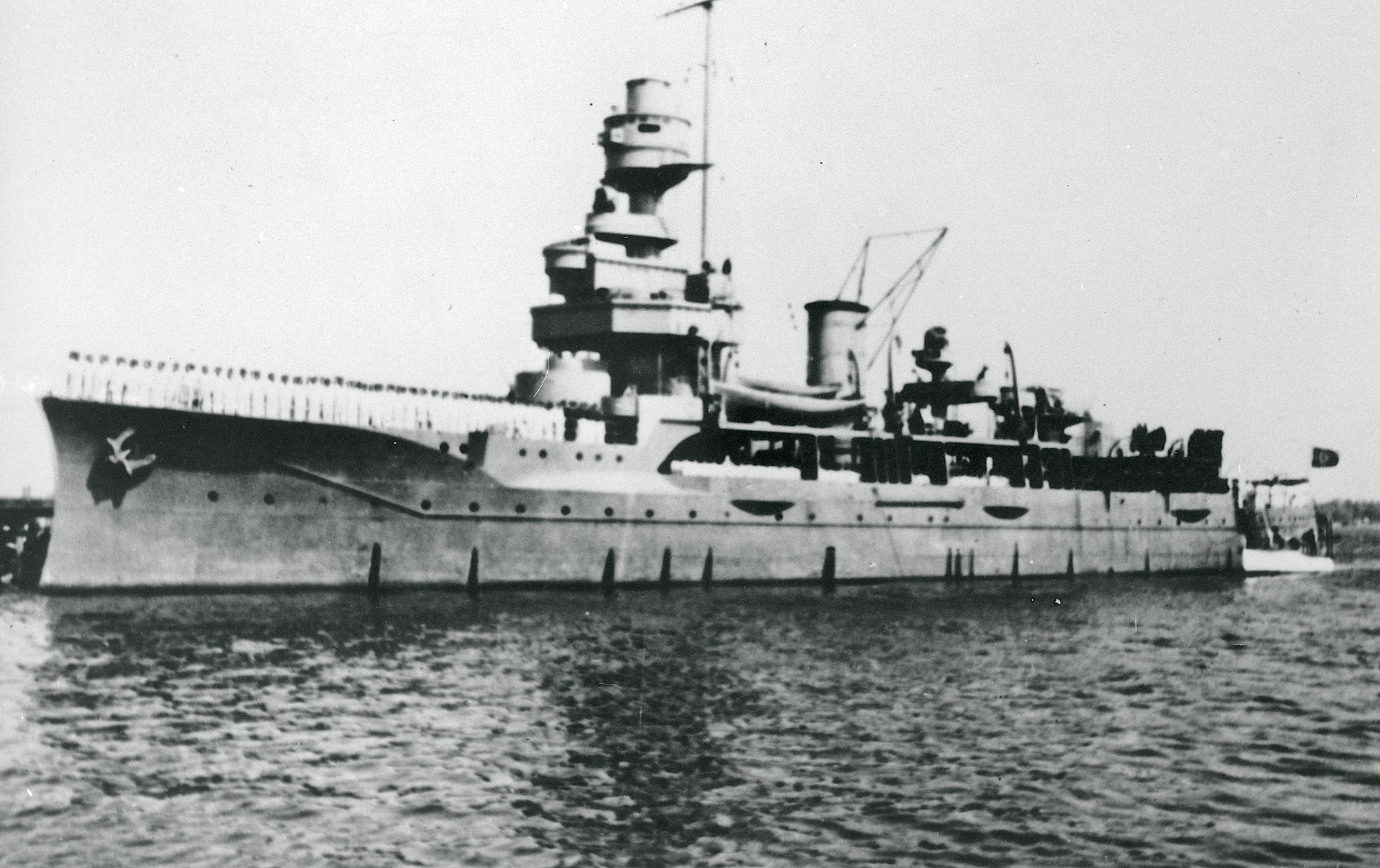

Above we see the Royal Danish Navy artilleriskib Niels Juel (also seen as Niels Iuel) in Aarhus harbor. In the background at the quay is the 1,300-ton cargo steamer Slesvig (Schleswig), belonging to the Danish-Fransk shipping company. Note the Danish flag recognition flashes on the warship’s forward turrets. She would give her last full measure for her country some 80 years ago this month.

The Danish Navy

While Denmark had a fairly decent series of light cruisers such as the Valkyrien and a couple of “bathtub battleships” or kystforsvarsskib— Iver Hvitfeldt (3,446 tons, 2 x 10″ guns, 8-inches armor) and Skjold (2,195 tons, 1 x 9.4″, 10 inches armor)– at the turn of the century, as a likely battleground for a tense naval build up between Imperial Germany and Great Britain, the country thought it would be a good idea in the early 1900s to whistle up some more modern warships.

This was exemplified by a trio of Herluf Trolle-class (~3,500 tons, 2 x 9.4″, 4 x 6″, 7 inches armor) coastal battleships completed by 1908.

Then came plans for a larger, more prestigious vessel that would carry 12-inch guns.

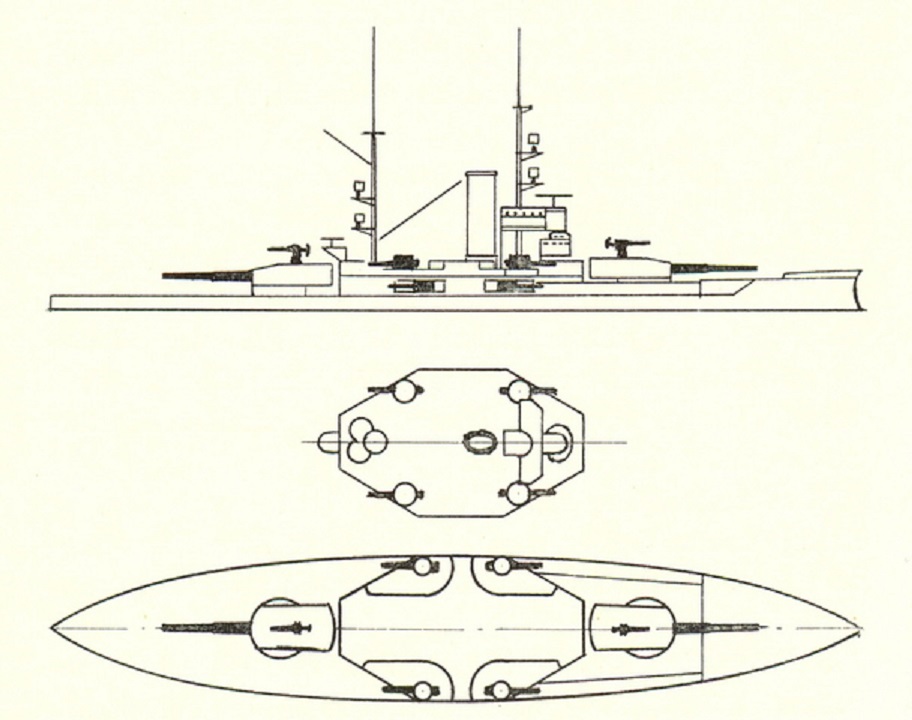

The initial design of this Danish “Orlogskibet” called for an enlarged Herluf Trolle with the 9.4-inch guns swapped out for a pair of Krupp-made 30.5 cm/50 (12″) SK L/50 guns— the same type used on the German Helgoland, Kaiser, König, and Derfflinger battleships and battlecruiser classes– ordered in July 1914 with magazines for some 80 shells for each mount. This armament would be augmented by a secondary battery of eight 10.5 cm/40 (4.1″) SK L/40 guns, the typical armament of many German light cruisers. A true “Balic battleship” akin to what was seen in use by Sweden and Norway at the time.

The thing is, these guns were soon embargoed as the Great War began and Germany was no longer interested in exporting any war material, even to a close neighbor whose neutral window to the west was cherished for numerous reasons.

This left the new vessel, which was laid down in September 1914 at Orlogsverftet, Copenhagen, to be launched in July 1918 just to clear the builder’s ways, to languish without guns that would never be delivered.

This left the Danes to come up with another idea.

Meet Niels Juel

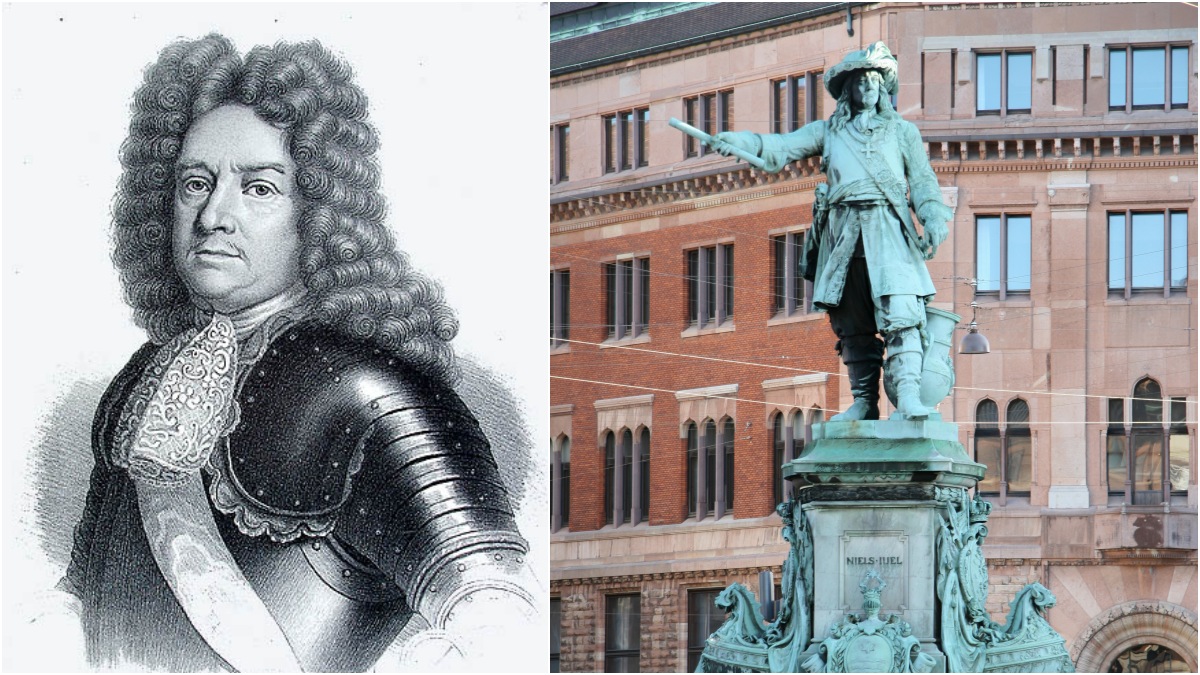

The name “Niels Juel” is in honor of the 17th Century Danish admiral and naval hero who, after learning his trade in Dutch service alongside Tromp and De Ruyter, would return home and raise Danish sea power to the point that it was one of the strongest fleets in Europe at the time– and beat the pesky Swedes to boot.

Niels Juel is well remembered in Denmark, and is one of the country’s biggest naval heroes, with a statue at Holmen Canal in Copenhagen.

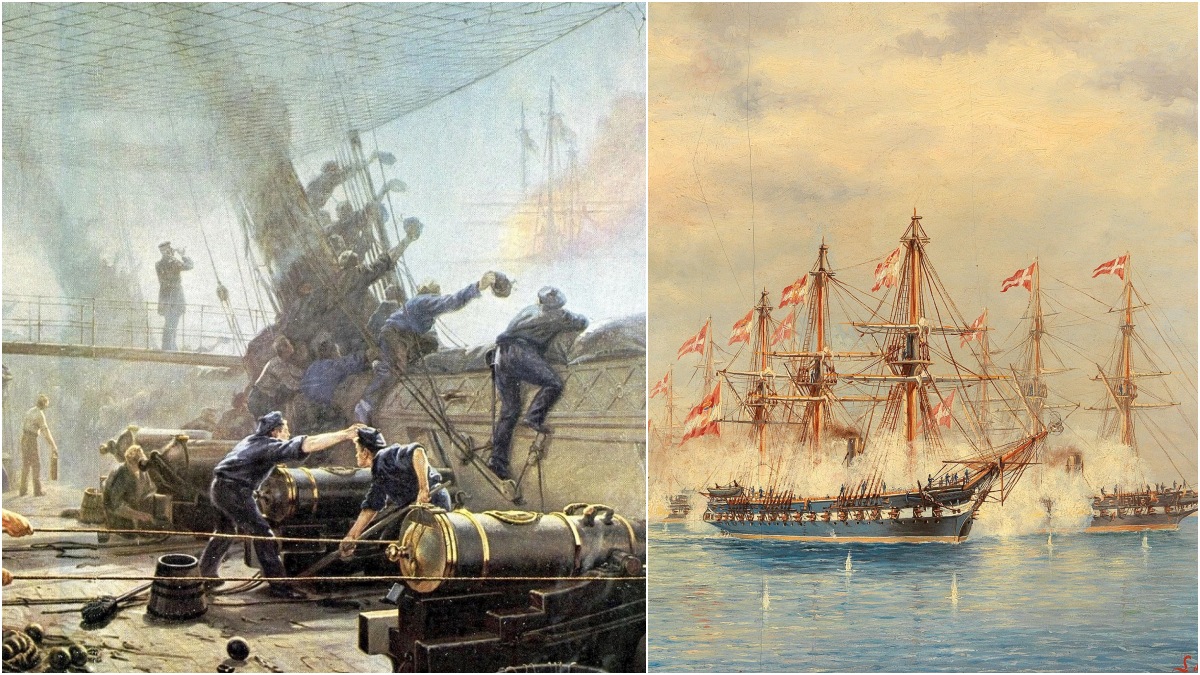

The first ship named in his honor, the 190-foot 42-gun screw frigate Niels Juel, built in 1856, would be one of three Danish warships under Commodore Edouard Suenson to fight the curious and brutal 13-hour long Battle of Helgoland— the last naval battle fought by squadrons of wooden ships in Europe– against Austrian Commodore Wilhelm von Tegetthoff’s stronger force in 1864 during the Second Schleswig War. She would survive the fight and be disarmed in 1888, kept as a barracks and training hulk into 1910.

Onboard the frigate Niels Juel during the Battle of Heligoland, May 9th, 1864, by Christian Mølsted ca. 1897-98 (left) and Battle of Helgoland by Ludwig Rubelli von Sturmfest, right, showing the Danish battle fleet in action against the Austrians.

This set up our new would-be-battleship for a great name to inherit.

With her original set of German guns never arriving, the Danes hit on an idea to convert the unfinished battleship to a gunnery training ship used for seagoing training of midshipmen, displacing some 4,350 tons, and running 295 feet oal.

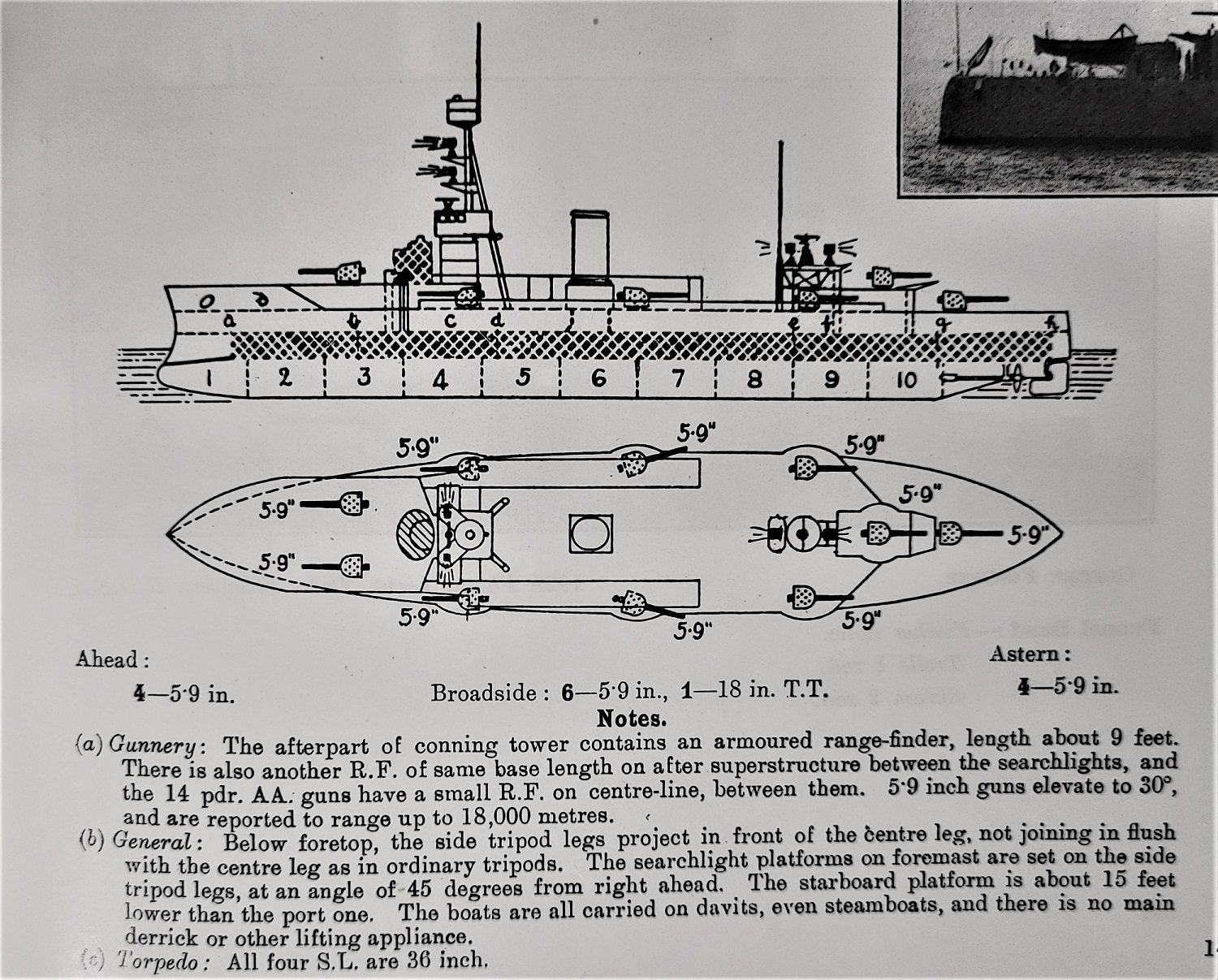

Her armament would be an all-up battery of 10 Krupp 15 cm SK L/45 guns— which were still available postwar– directed by two Zeiss rangefinders, augmented by four of 57mm (14 pounders) A.B.K. L/30 AAA guns, and a pair of submerged port and starboard 17.7-inch torpedo tubes with room for four heater style fish. The machinery would be a quartet of British-supplied Yarrow boilers (two coal, two oil-fired) powering triple expansion engines for a total of 5,500 hp on two screws– good for 16 knots. Armor was Krupp-style cemented plate made by Bethlehem in the U.S. and include a 7.75-inch amidships belt, 6 inches on the bulkheads and CT, and 2 inches on the gun shields and deck.

She was not completed to this modified plan until 23 May 1923, her construction spanning almost a decade. Still the largest ship in the Danish fleet, she was the local equivalent of the HMS Hood as far as Copenhagen was concerned although the three smaller Herluf Trolle-class vessels carried larger (9.4 inch) guns.

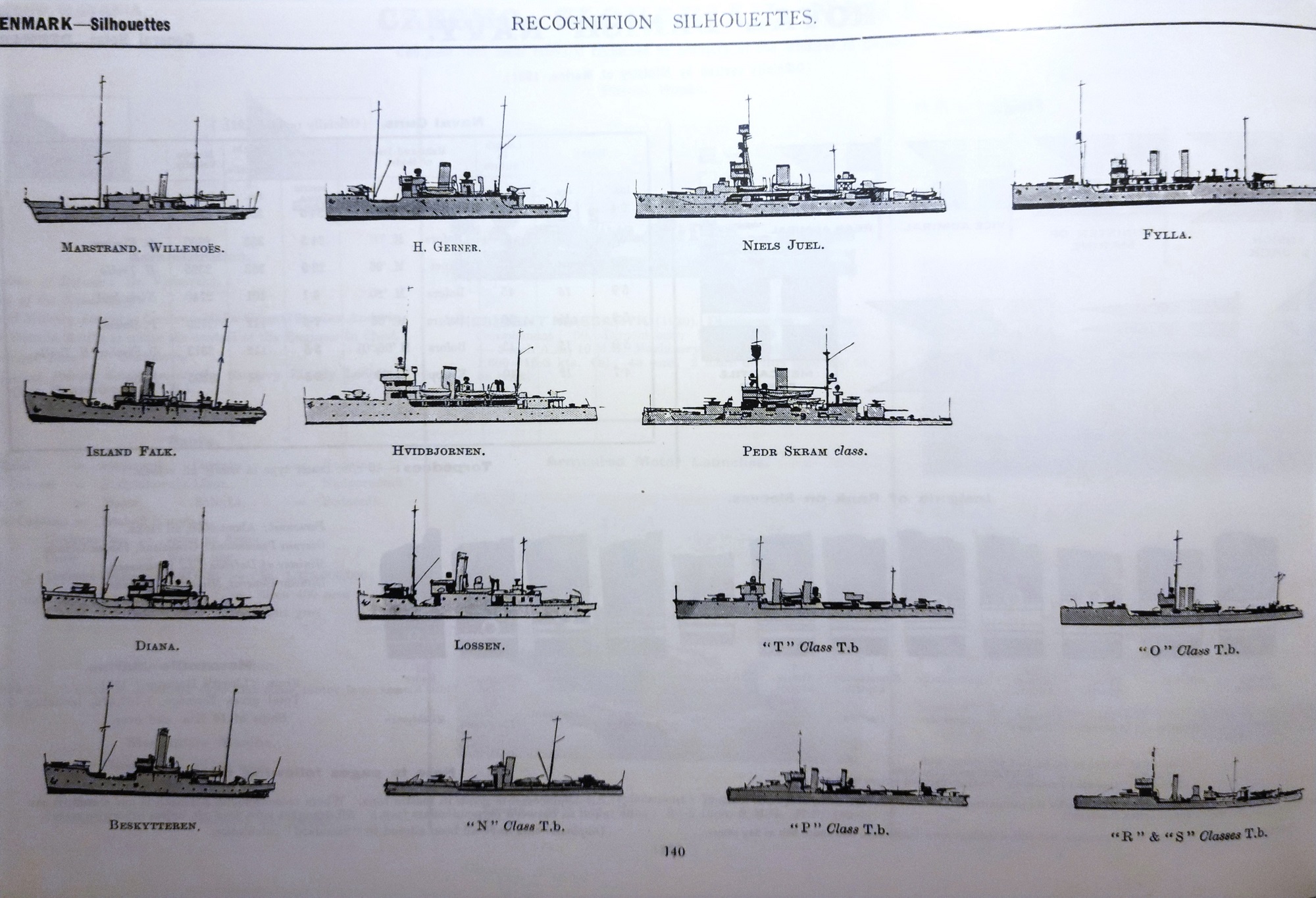

The 1930s fleet was rounded out by some 20-30 assorted torpedo boats, a dozen small submarines, and a host of sloops (including the old HMS Asphodel sold to Denmark in 1920 and renamed Fylla), mine warfare vessels, and fisheries patrol boats.

Happy service

Soon after she entered service, Niels Juel became the command ship for the Artillery School and for the Training Squadron. She immediately embarked on a series of visits to Danish colonies in the Faroe Islands and Iceland, as well as port calls in neighboring friendly ports such as Bergen, Leith, and Gothenburg.

October 1923 saw her complete a six-month cruise to South America.

The battleship Niels Juel with Christmas greetings from Rio de Janeiro, 1923. Note her early tripod mast. THM-16006

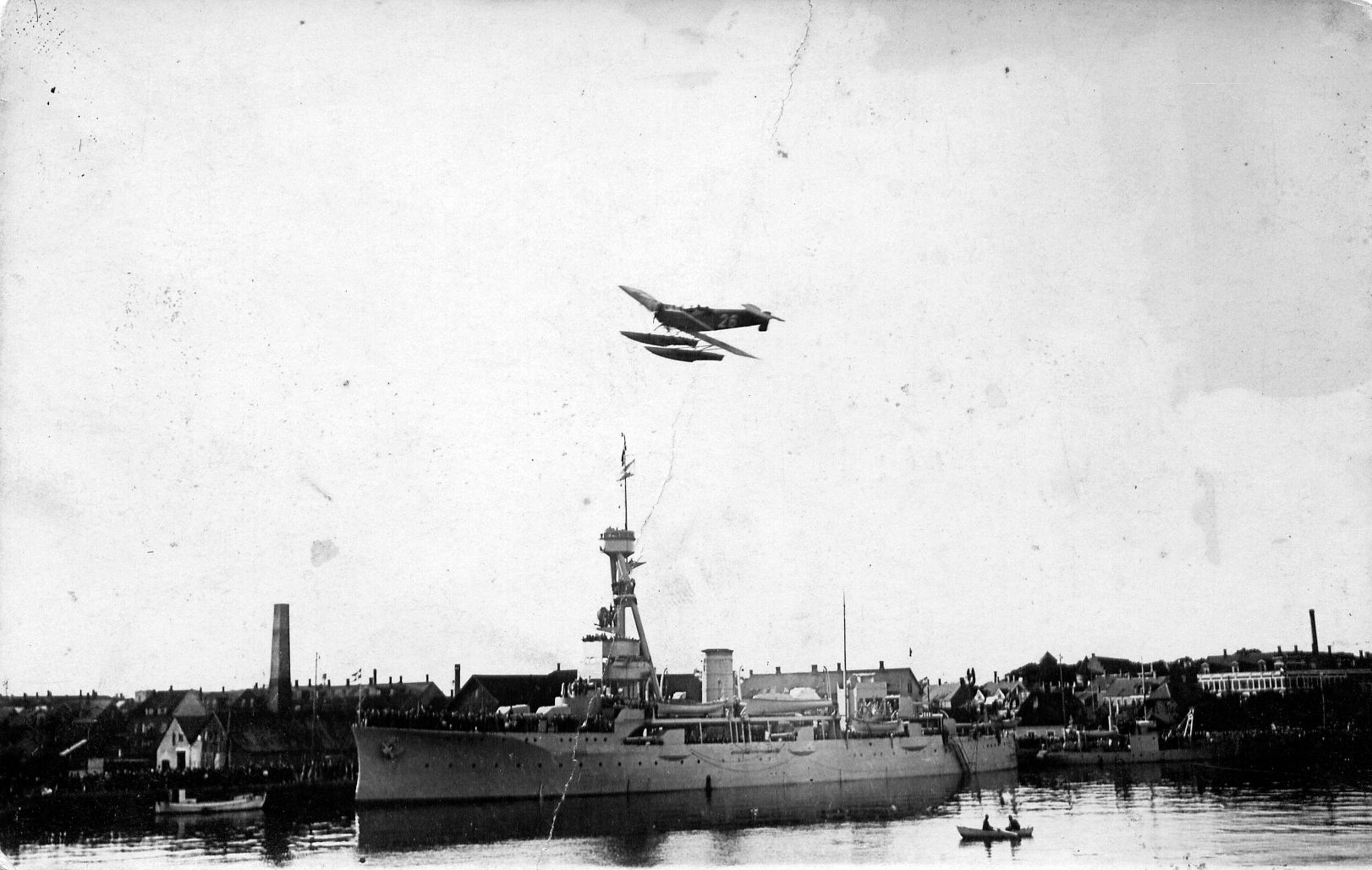

Niels Juel (built 1918) at the quay in Køge Havn, seen to port. A Hansa-Brandenburg W. 29 (HM1) reconnaissance aircraft with the number 26 is seen in the air. Taken in the 1920s. THM-26156

She carried Danish King Christian X to the Faeroe Islands and Iceland in June 1926, then again in 1930, as well as a royal trip to Finland in 1928 and a Mediterranean trip in 1929 which included bringing a Danish delegation to the Barcelona Universal Exposition. These trips were commemorated by Danish maritime artist Benjamin Olsen and are in the archives of the Forsvarsgalleriet.

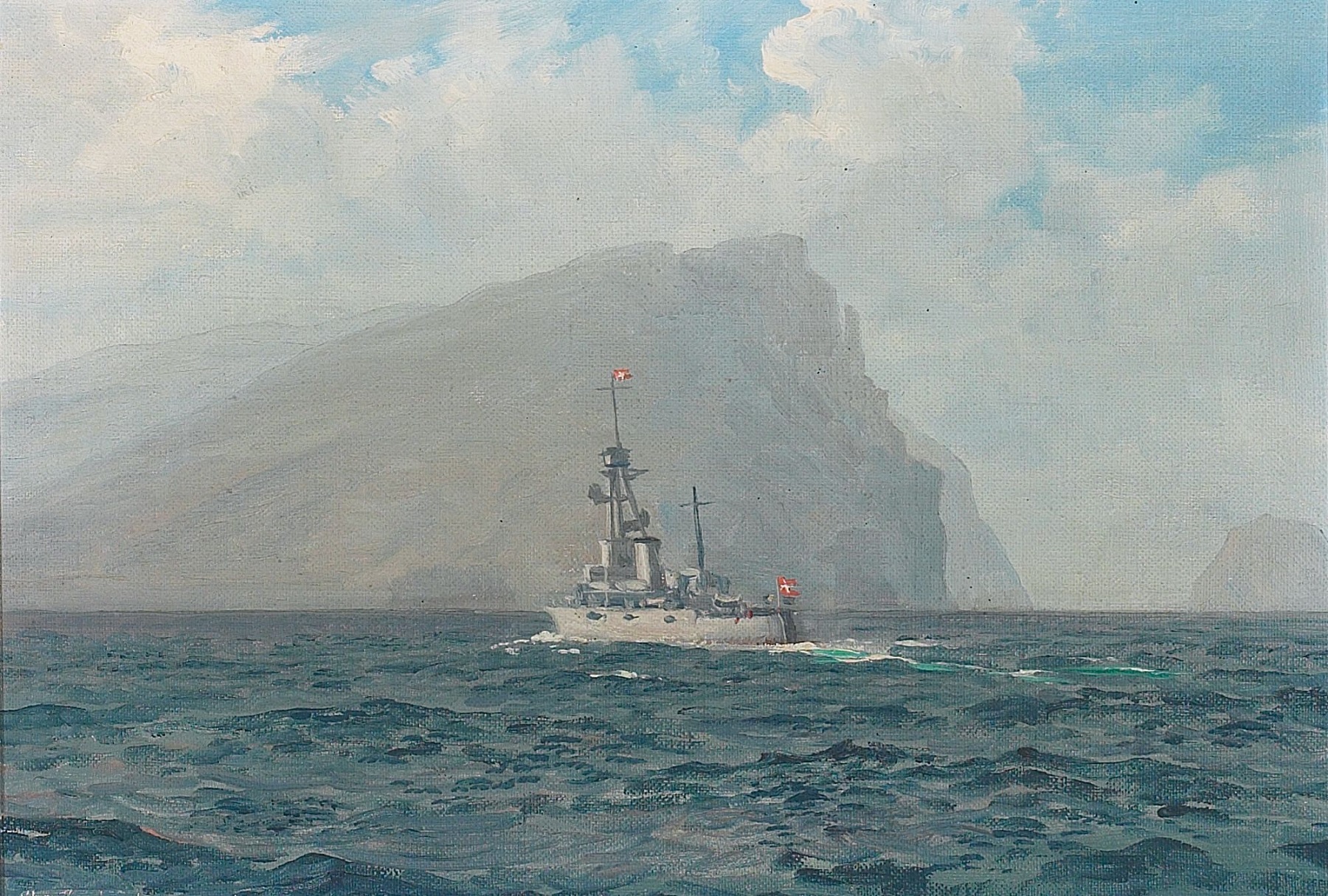

Niels Juel at the Trøllkonufingur in the Faroe Islands on June 6, 1926. The Niels Juel carried the Danish King Christian X to the Faeroe Islands and Iceland in June 1926, accompanied by two other Danish naval vessels. Benjamin Olsen seems to have been part of the entourage. By Benjamin Olsen 1926 via the Forsvarsgalleriet.

The Niels Juel saluting the Finnish State vessel Eläköön. The experts at Bruun Rasmussen assumed that the occasion was the visit of the Danish King Christian X to Finland in May 1928. The Eläköön was built in 1886 while Finland was still a part of the Russian Empire. It served as a pilot ship, and after 1918 it was retained in Finland as a state ship, serving also as a presidential yacht when needed. By Benjamin Olsen 1928 via the Forsvarsgalleriet.

The Niels Juel saluting Spanish dignitaries in the Harbor of Barcelona during the 1929 Barcelona Universal Exposition. The Niels Juel visited Barcelona as part of a Mediterranean training cruise for aspiring officers. To the left are seen two Italian Turbine class destroyers, the Euro (ER) and the Nembo (NB). By Benjamin Olsen 1929 via the Forsvarsgalleriet

Niels Juel and Fylla in Oslo, Norway July 7, 1930. The paintings show the Danish coastal defense ship Niels Juel (left) and the gunboat Fylla saluting the Norwegian King in Olso. The two vessels carried the Danish king Christian X to the Faeroe Islands and Iceland from June 1930, so this visit must have been on their way home to Copenhagen. Benjamin Olsen seems to have been part of the entourage. By Benjamin Olsen 1930 via the Forsvarsgalleriet.

The coastal defense ship Niel Juel gun-saluting at Iceland. Between 1923 and 1939. By Benjamin Olsen. Auctioned at Sotheby’s, London on November 30, 2005. Lot W05705/215.

Other trips around the Med in the winter months and the Baltic in the summer were common throughout the 1930s.

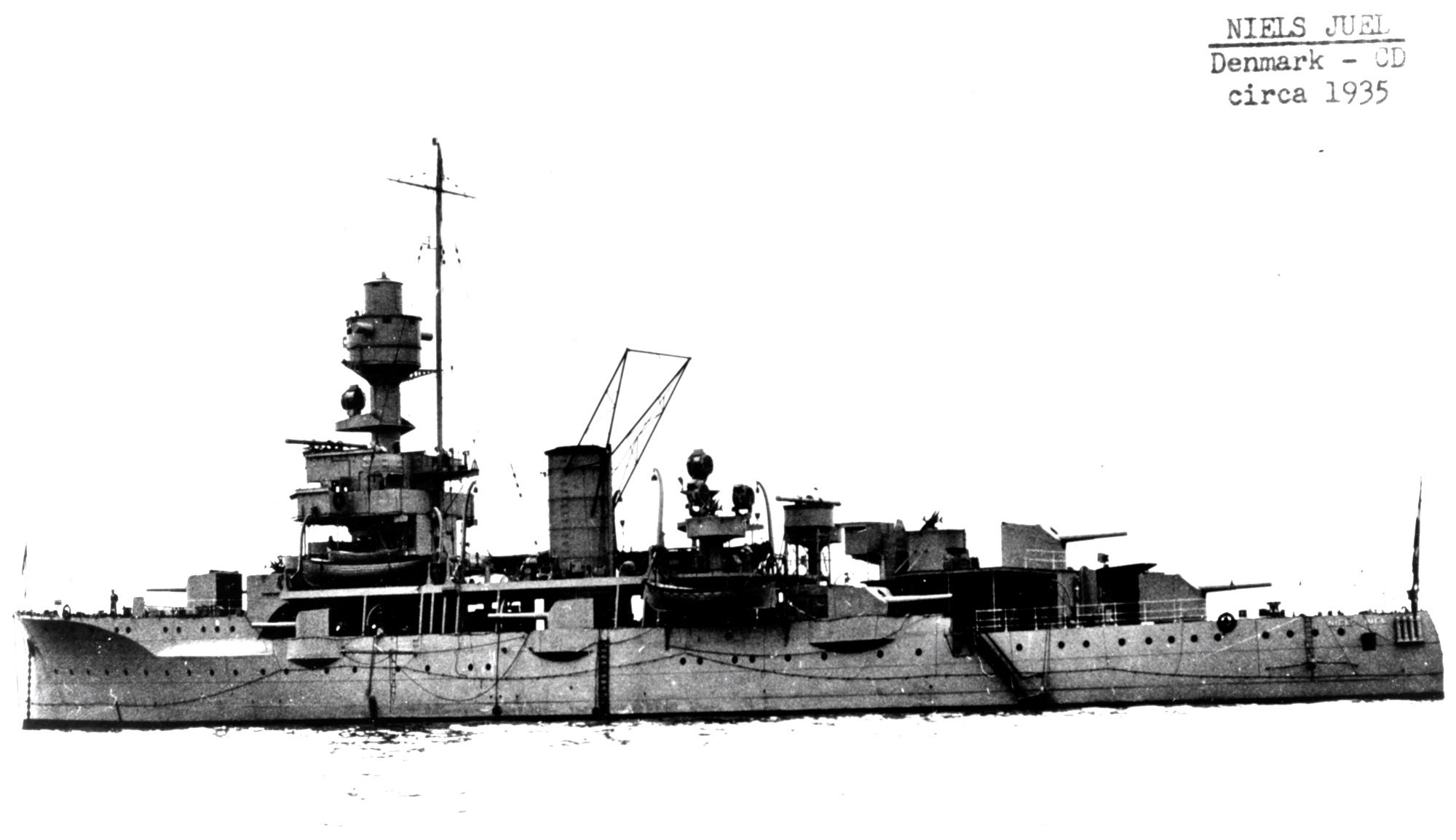

A series of incremental upgrades and modernizations between 1929 and 1936 saw a new mainmast fitted, her old 3-meter Zeiss rangefinders replaced by much more effective 6-meter models and her four 57mm AAA guns swapped out in favor of 10 more modern Madsen/DISA 20mm cannons, the latter one of the better AAA guns of the 1930s.

HDMS Niels Juel pictured on sea trials at Copenhagen post her major refit on July 10th, 1936 courtesy of Mr. Brian James

Niels Juel (Danish Coast Defense Ship, 1918-1952) Photographed after July 1, 1936, following a refit to receive a new mainmast. NH 88491 & THM-22287

War!

Denmark tried to be as neutral in WWII as it had been in 1914-1918 but Germany wasn’t having it and blitzkrieged the country in a lopsided invasion (Operation Weserübung – Süd) on 9 April 1940. The interwar Danish government, which had been controlled by socialists in the 1920s and 30s, had gutted the military and, while the rest of Europe was girding for the next war, the Danes were laying off career officers, disbanding regiments and basically burning the bridge before they even crossed it.

Five Danish soldiers with a 37mm anti-tank gun outside Hertug Hansgades Hospital in Haderslev on the morning of 9 April 1940 Denmark. They were ordered to lay down their arms before noon.

This made the German invasion, launched at 0400 that morning, a walkover of sorts, and by 0800 the word had come down from Copenhagen to the units in the field to stand down and just let it happen. That doesn’t mean isolated Danish units didn’t bloody the Germans up a bit. In fact, they inflicted some 200 casualties on the invaders while suffering relatively few (36) of their own. (More on that in detail here)

The peace agreement reached with Berlin allowed the country to still be sort of independent, although extensively garrisoned by the Germans, while the Danish military would still be allowed to exist, just deprived of fuel, and largely kept under lock and key by their new friends.

Of course, that didn’t stop extensive Free Danish forces to be formed overseas, most of the Danish merchant marine to sail for the Allies– over 5,000 Danish merchant sailors manned over 800,000 tons of shipping for the Allies, many never to be seen again– and the training ship Danmark, in the U.S. in 1940, to train over 5,000 Americans for while operating for the USCG. Two small Danish Navy fisheries patrol boats, Maagen and Ternen, were in Greenland and would serve the Allies.

God Save the King, God Save Denmark, Destroy the Ship!

Then came August 1943, with Danish workers on strike in Odense and Esbjergwhen and a growing homegrown resistance movement, the Germans decided that, with the invasion of Sicily and the perceived increased threat to an Allied invasion in Northwest Europe, they enacted Unternehmen Safari (Operation Safari), a “state of emergency” and on 29 August 1943 the Danish government and military had its mandate canceled.

There was resistance, with the Danish military suffering about 100 casualties and inflicting about 70 on the Germans. Many armories had a chance to spike their weapons and remove the bolts from their rifles before the Germans swarmed in.

Danish weapons after the disarmament of the Danish soldiers on 29 August 1943 at Næstved Barracks in connection with the state of emergency. The weapons were destroyed before being seized. FHM-170310

As for the Navy, in a pre-arranged signal and in an ode to the epic scuttlings of the Dutch fleet at Java and the Vichy French fleet at Toulon the previous March and November, respectively, Danish RADM Aage Helgesen Vedel flashed a prearranged signal– K N U — instructing all his crews to attempt to sail for neutral Sweden or scuttle their ships.

Across Denmark, the Danes gave their own fleet the hard goodbye and fought off the arriving Germans in the process, with at least nine Danish sailors killed and around a dozen seriously wounded in the process.

Some 32 Danish ships– two-thirds of the fleet– were wrecked within hours. An impressive feat considering most were in and around Copenhagen and the fast-moving German troops were literally pulling up at the docks while the scuttlings were underway. The Germans kicked off Safari at 0400, Vedel flashed his order at 0408, the first scuttling charge was blown at 0413, and the last one went off at 0435.

Following the operation, the senior-most German Kriegsmarine officer in Denmark, VADM Hans-Heinrich Wurmbach, told Vedel, “We have both done our duty.”

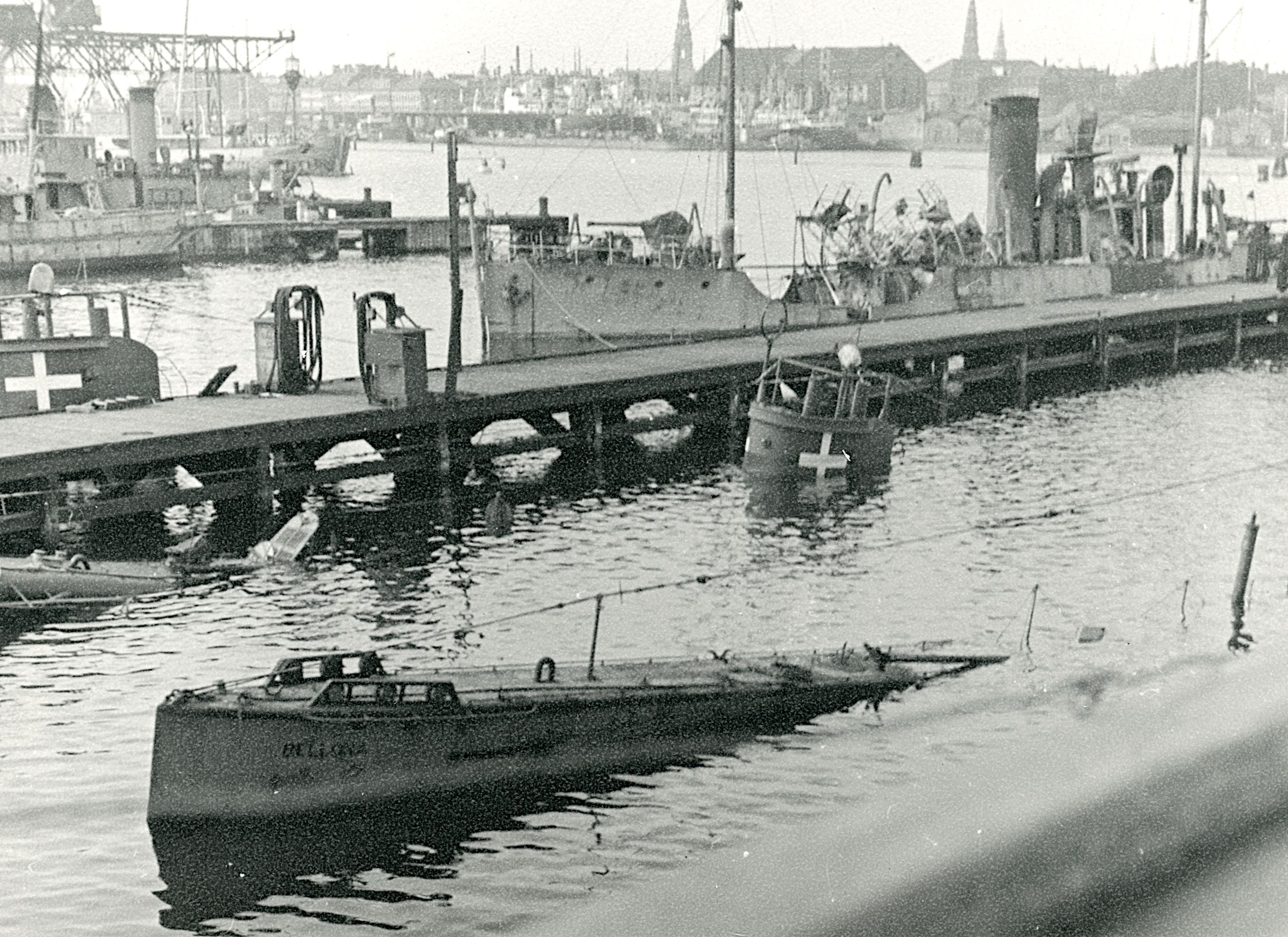

Danish warships after the fleet’s sinking at Holmen in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August 1943. From the right is seen the artillery ship Peder Skram, torpedo boat Vb. 2, and the motor torpedo boat Hvalrossen (only the masts are visible). In the background is the frigate Fyn. FHM-166686

Danish warships at Holmen after the sinking of the fleet in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August 1943. Here the minesweepers Laaland (right) and Lougen (left) are seen sunk in the Søminegraven. FHM-166766

Danish warships at Holmen after the sinking of the fleet in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August 1943. In the foreground are the submarines Bellona and Havmanden. Behind these workshop ship, Henrik Gerner. FHM-166843

Sailors with life belts on board the inspection ship Hvidbjørnen before the ship was sunk in Storebælt off Korsør on 29 August 1943. The sinking took place in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August. FHM-167263

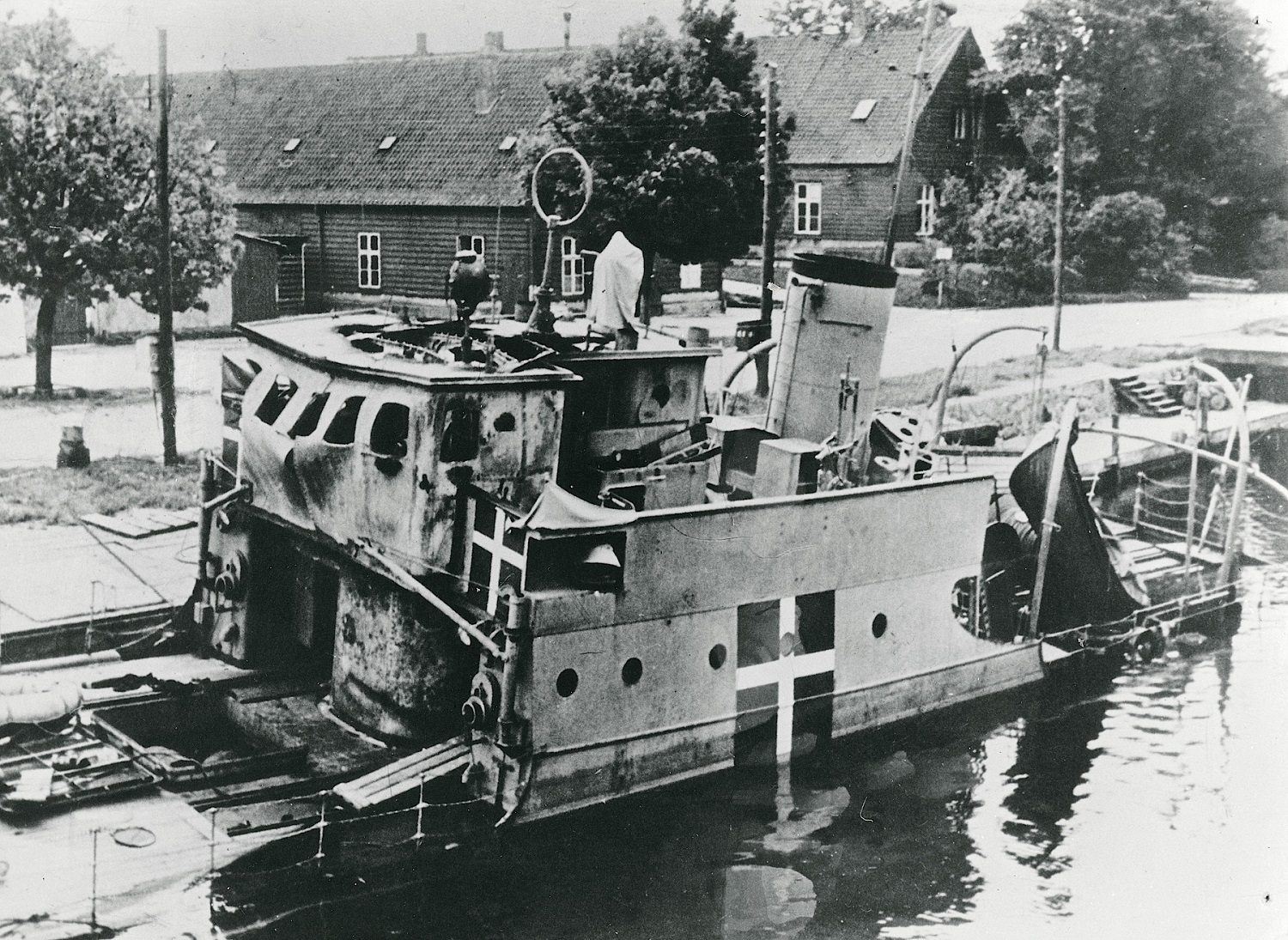

The minesweeper Søbjørnen on Holmen after the sinking of the fleet in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August 1943. FHM-166994

The minesweeper Lougen on Holmen after the sinking in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August 1943. FHM-166807

Only 14 Danish ships were taken intact by the Germans, but they were generally of low value (survey ships, minesweepers, inspection boats, barracks ships, etc.), were decommissioned, or were still under construction and uncrewed.

Four small fast movers– the torpedo boat Havkatten, and minesweepers MS 1, MS 7, and MS 9, reached the safety of Sweden– where they formed a Danish naval flotilla in exile that would sail back with their flags flying proudly in May 1945.

But what about our Niels Juel?

The pride of the Danish fleet was the largest warship flying the Dannebrog to attempt to displace to Sweden. Unfortunately, with a speed of just 14 knots and harried by German Heinkels and Stukas, she couldn’t clear the water from Holbaek to Malmo.

Niels Juel leaves Copenhagen, on 26 August 43, on her last trip. Note the Danish recognition flash added after 1940. FHM-165422

The running battle saw the Danish ship, under skipper CDR Carl Westermann, exchange hot fire with German bombers, then, once the outcome was clear, strike her flag and leave her on the bottom, suffering five casualties. It is known today in Denmark as the Battle of the Isefjord.

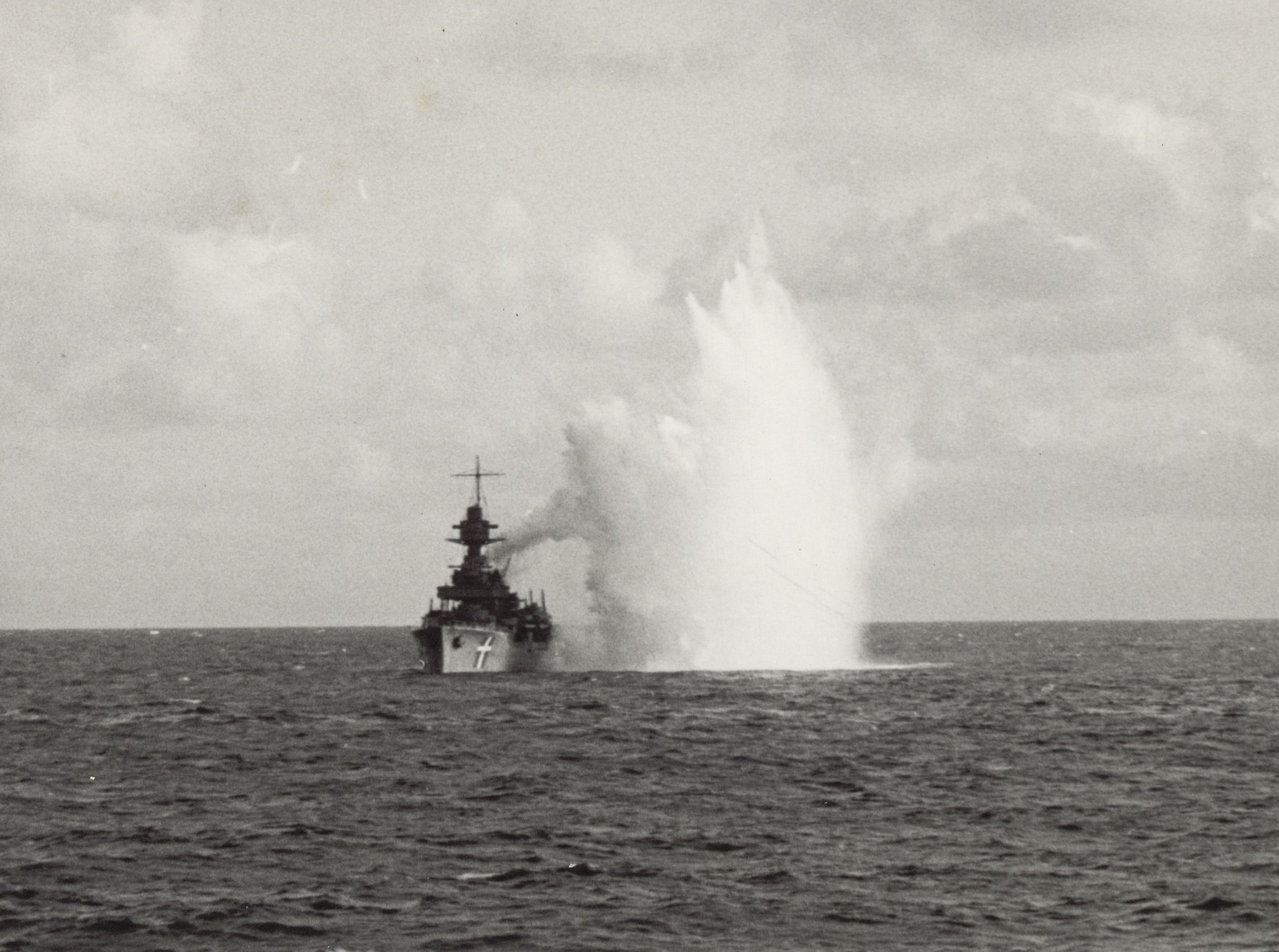

The artillery ship Niels Juel is bombarded by German planes north of Hundested, when the ship, according to orders, searched for a Swedish port on 29 August 1943. FHM-167241

As told by one of her officers, in a 1945 issue of Proceedings:

August 27th, we had called at Holbaek and were supposed to stay over Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I had leave from Sunday, 9:00 P.M. and intended to take a trip home. We understood that something was wrong because nobody got liberty Friday night, and I figured I had to give up the idea of going home. Friday night at 11:00 P.M. orders were given to fire up under all boilers and to prepare to leave port any minute- Rumors went wild all over the ship and Saturday afternoon two of our men went up to the commander, Captain Westermann, and requested an explanation. We were told that we were supposed to defend ourselves with all means if necessary. So, we knew that this was it. We reinforced all watches, and when I had to go on watch at 4:00 A.M. nobody doubted any longer that something would happen. I served as messenger for the Captain and I had just brought him a message when he came out to the commander of the watch and gave the order “Clear ship for action.” Within a moment all guns were manned.

It was pitch dark, but it did not last long until all was in readiness and with the first sign of dawn breaking, we left the pier. I had managed to get a letter on shore which I had written the evening before. In it I had given an account of the situation. Little did I expect to see any of you again. It seemed to me that there was only one way out. To try to escape to Sweden or fight until the ship sank.

It was a gray morning with low-hanging clouds. We were looking out sharply for enemy planes. The tug which had towed us lowered the flag and everybody aboard took off their hats as we passed by.

We sighted a German plane at the horizon but it disappeared soon. We hoisted ammunition up to the big guns on our way out. While sailing through the Isefjord, coffee was brought up to us. Nothing was rationed any longer and we distributed all our cigarettes among the gun crews. Morale was high and everybody was in good spirits in spite of the seriousness of the situation.

After having traveled for half an hour, orders were given for action stations. The enemy had been sighted off Hundested, one heavy cruiser and two destroyers. We were out of range, as yet, but everything was being prepared. Their superiority was definite but we had to engage them and we wanted to.

We were right off the pier of Hundested when one of our mine-sweepers signaled that the enemy had mined the entrance of the firth all night long. From the bridge we were told that we would try to force the barrage some 400 meters from land and hold our course. Only a moment later, we saw bombers circling around us at proper distances but we could not see how many there were as they kept flying in and out of the clouds. Suddenly a Heinkels dived on us, strafing our deck with cannon fire. A few were wounded. The plane disappeared in a jiffy, but by now we were all set. The next one got a hot welcome and was shot down. The next again dropped two heavy bombs which narrowly missed our quarter-deck, while a couple of others strafed our deck with cannon. It was almost unbearable. Shell fragments and projectiles kept on whizzing around us. It was hardly believable that so few of us were killed or wounded. One howled terribly, another was taken down to the sickbay on a stretcher unconscious. A mate came running along and told me that warrant officer Andreasen was killed. He was gun captain of an anti-aircraft gun. The gun had been hit and the crew had taken cover. I ran up there right away and found him lying on the platform. I thought him dead but suddenly he moved and groaned. At that moment, two planes dived and opened fire. That was the only time I got the chills. There was no cover so I flung myself down and grasped Andreasen’s hand. The poor soul yelled when they started shooting. He had been hit in the belly and was scared. A big iron splinter struck off the platform. The whole deck was desolate, only the gun captains had taken cover behind the rail after sending their crews down. Only the anti-aircraft guns remained manned but, of course, they were the only ones which had something to harvest.

When the planes had gone, another warrant officer came and got Andreasen down. In the meantime, however, the captain had received orders to go back: the enemy ships had been reinforced.

Then came the Stukas.

They came howling and screaming from ’way up high and let go their bombs. The detonation seemed to be right under us and we jumped up into the air. All lights in the whole ship went out, and we discovered a leak in the port coal bunkers. The bunker door in the deck was flung up, and people on land told us later that the only thing visible of the whole ship was the stem. It was probably two 250-kilo bombs. Now we set the course toward land for full speed and prepared to abandon ship. The Diesel engines were smashed and we had to pack the most necessary things in complete darkness. When we took the ground, foot valves were removed and thrown overboard and all suction valves were opened. The ship went down and sank deeply into the bottom.

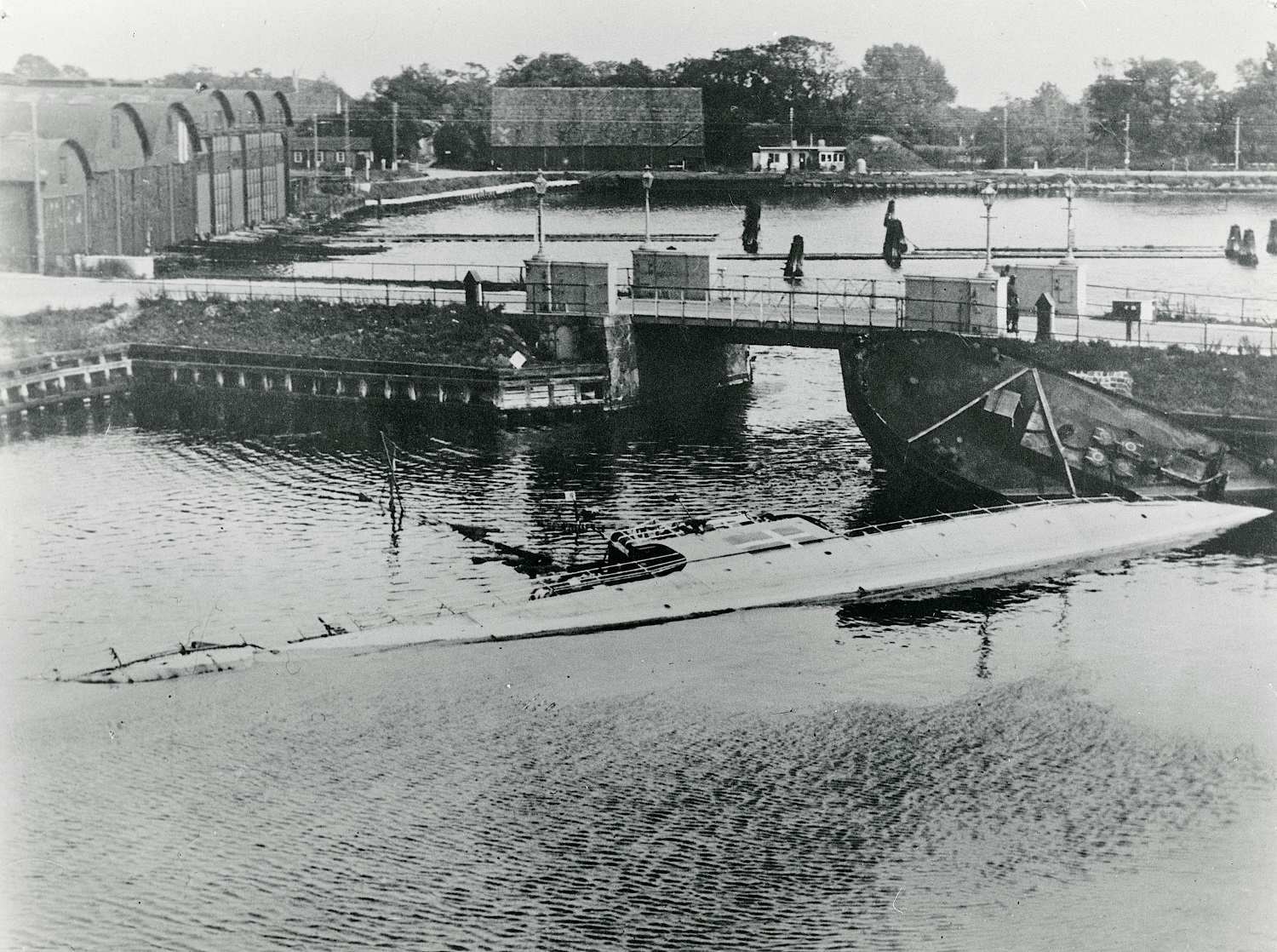

“The artillery ship Niels Juel ran aground in Nykøbing Bay after an unsuccessful attempt to sail to Sweden on 29 August 1943. The escape attempt took place in connection with the state of emergency on 29 August. The ship is salvaged by a salvage vessel from Svitzer.” FHM-167255

Sadly, the Germans were able to raise the damaged Dane in October, and, landing her guns for use in coastal fortifications, tow her to Kiel for repairs. They ultimately put her back into service as the training ship Nordland in September 1944, operating in Polish waters.

Ex-Niels Juel/Nordland withdrew to Kiel to escape the oncoming Soviets and, at the end of the line, was scuttled in May 1945 in the Eckernførde inlet in 92 feet of water.

Epilogue

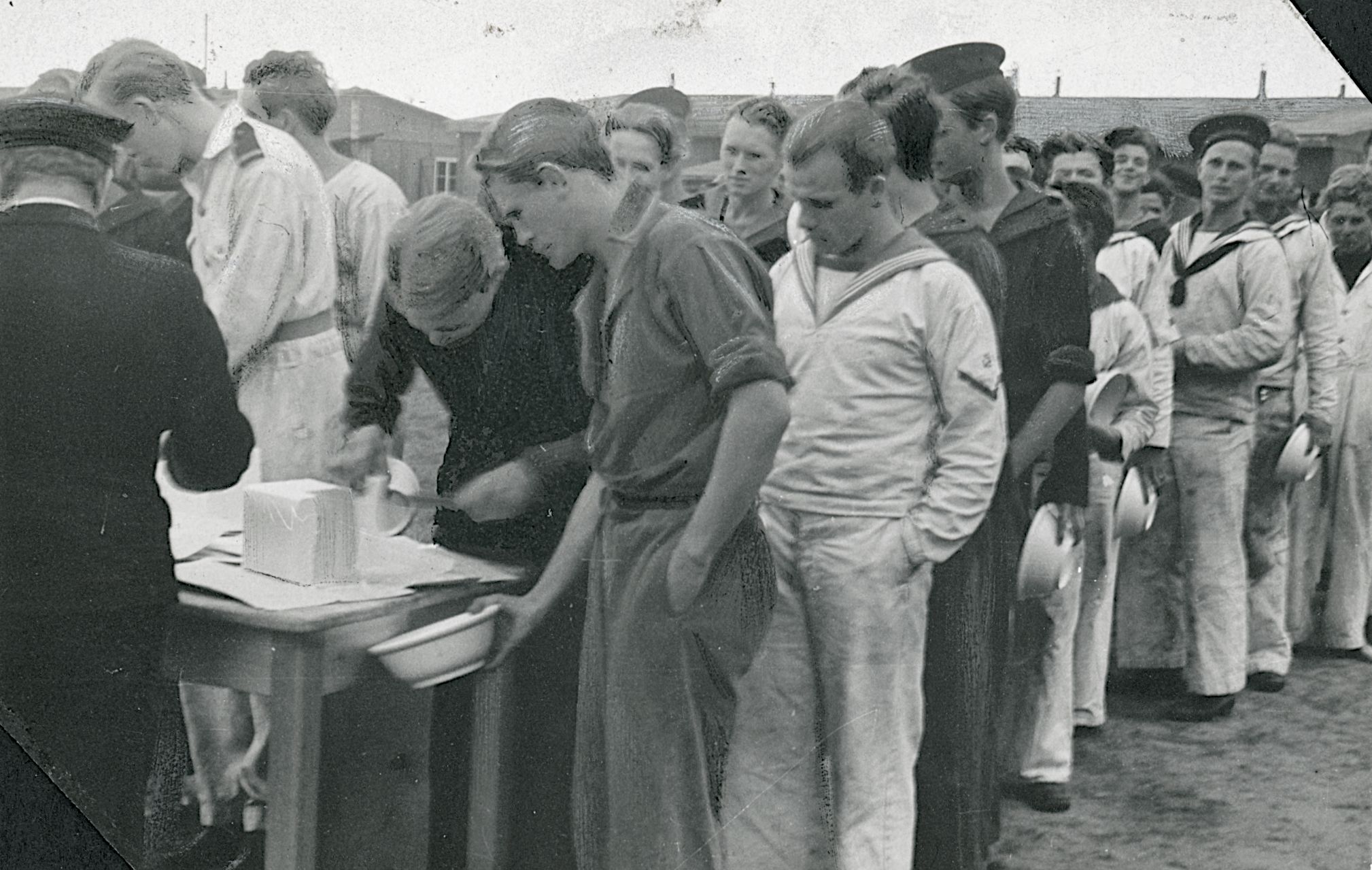

The Germans interned most of the captured Danish sailors and officers such as at the Tårnborglejeren arena and at the KB-Hallen arena in Frederiksberg to include Westermann and Vedel.

Ice distribution in Tårnborglejeren near Korsør, where the crews from the inspection ships Hvidbjørnen and Ingolf were interned after the Germans declared a state of emergency on 29 August 1943. FHM-174949

The sites were, however, closed in October 1943 and the men were paroled. Most subsequently took to a range of resistance activities. Vedel began interfacing with the British and, in May 1945 when the Allies came to liberate Denmark, immediately began working with Royal Navy VADM Reginald Vesey Holt to supervise German disarmament and minesweeping work. He later served as the Danish Flag Officer to NATO, retired from the Navy in 1958, and passed in 1981.

The usable 5.9-inch guns from Niels Juel, which were landed in Denmark before the hulk was towed to Kiel, were installed by the Germans in a new coastal defense fort near Frederiksberg to defend the Jutland peninsula. Surrendered to the Danes in 1945, they remained in service until 1962 and Bangsbo Fort is today a museum.

The wreck of the old Niels Juel was sold by the Danish government to the salvage firm of Em. Z. Svitzer in 1952, and most of the superstructure was raised to be scrapped. Her hull, however, is still in the Eckernførde.

The Danes reused her name, with the third Niels Juel being the lead ship (F 354) of a class of handy corvettes that remained in service from 1980 to 2009.

Starboard-bow view of the Danish Navy Frigate HMDS Niels Juel (F 354) underway in the Baltic Sea on the coast of Ventspil, Latvia, while participating in BALTOPS 2005. 330-CFD-DN-SD-07-00068

The fourth Niels Juel (F 363) is an Iver Huitfeldt class frigate that was laid down in 2006 and commissioned in 2011. Her motto is Nec Temere, Nec Timide (Neither reckless nor timid).

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO, has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!

Pingback: Last stand of the Danish Army | laststandonzombieisland