Warship Wednesday, Oct. 13, 2021: Tokyo Express

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Oct. 13, 2021: Tokyo Express

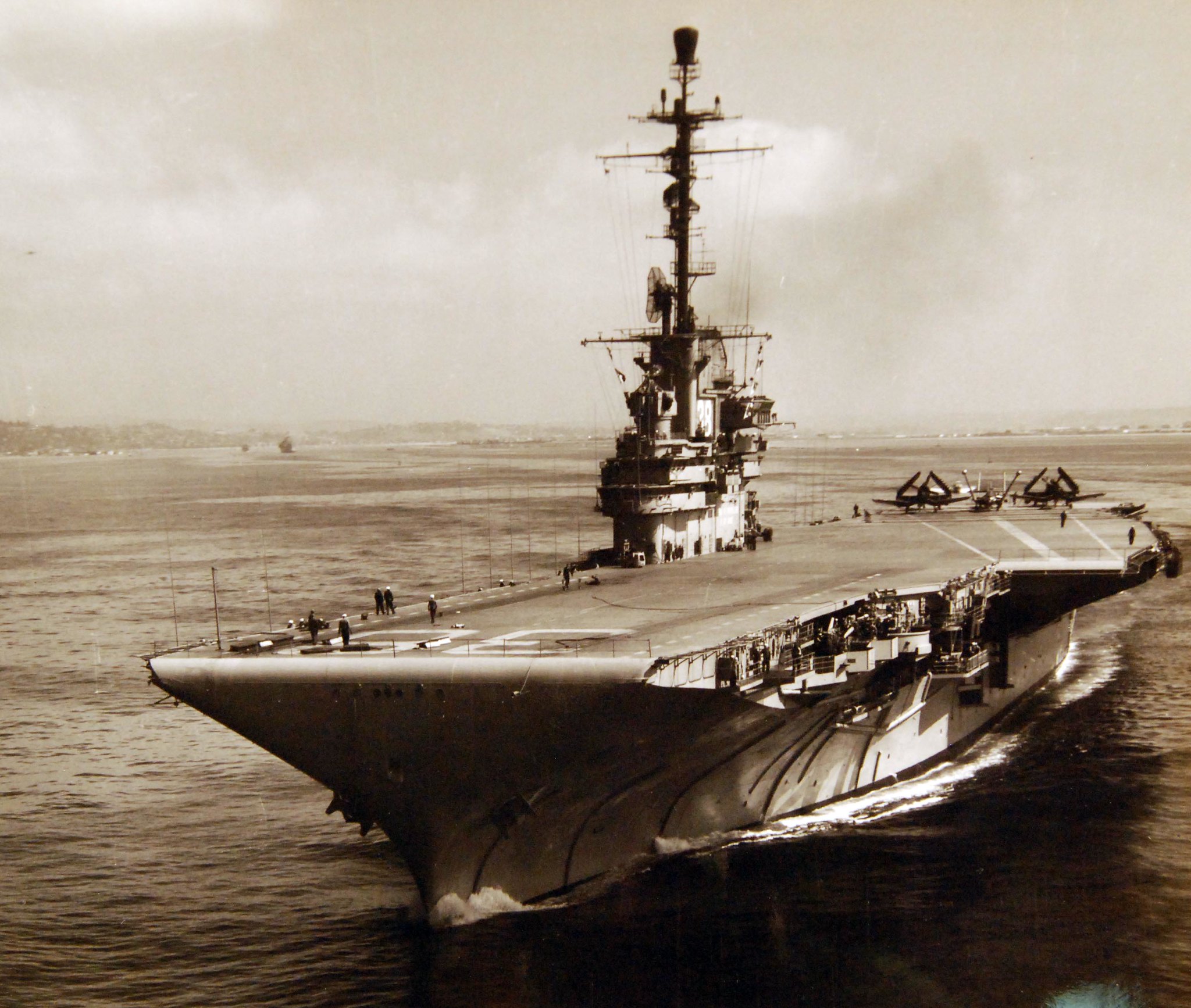

Here we see the modified Essex-class attack carrier USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) off Gibraltar, 13 October 1963– 58 years ago today and the traditional birthday of the U.S. Navy, as a matter of fact. Just as the fabled rock holds a key place in British history, “Shang” holds a singular role in American naval history and lore.

The 12th aircraft carrier of the Essex class and the 20th fleet carrier to be commissioned into the U.S. Navy, Shangri-La as far as I can tell is the only American flattop ever named after an entirely fictional place. As something of wink-wink disinformation for the daring raid on military targets at Tokyo, Yokohoma, Osaka, and Kobe, by 16 stripped-down USAAF B-25B Mitchell bombers of Maj. Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, flying from USS Hornet (CV-7) in April 1942, FDR chalked up that the bombers flew from “Shangri-La,” referring to the fictional Tibetan utopian of the 1933 James Hilton novel Lost Horizon.

The first true mass-market paperback, at 25-cents a pop, Lost Horizon was the best-selling novel of 1939 and Roosevelt was evidently a fan. For instance, the low-key (and top-secret) Presidential country retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin mountains established by FDR and filled with furnishings drawn from the White House’s attic was named Shangri-La.

Laid down at Norfolk Naval Shipyard exactly eight months after the Japanese strike at Pearl Harbor, our ship was technically a “Long Hull” Essex type, sometimes referred to as a Ticonderoga-class. In a salute to the Doolittle Raiders, her christening sponsor was “Mama Joe,” Mrs. James H. Doolittle (nee Josephine Elsie Daniels).

Her 15 September 1944 commissioning at Norfolk took place before a crowd of 100,000 people. She would spend the rest of the year in shakedowns off the Atlantic coast and in the warm waters of the Caribbean.

Aerial view of USS Shangri-La (CV-38) underway, painted in Measure 33, Design 10A camouflage. This photo was probably taken in the Gulf of Paria, Trinidad, B.W.I, during the ship’s shakedown cruise, September–December 1944. Note destroyer steaming astern of Shangri-La (top left corner of the photo). BuAer photo # 301910.

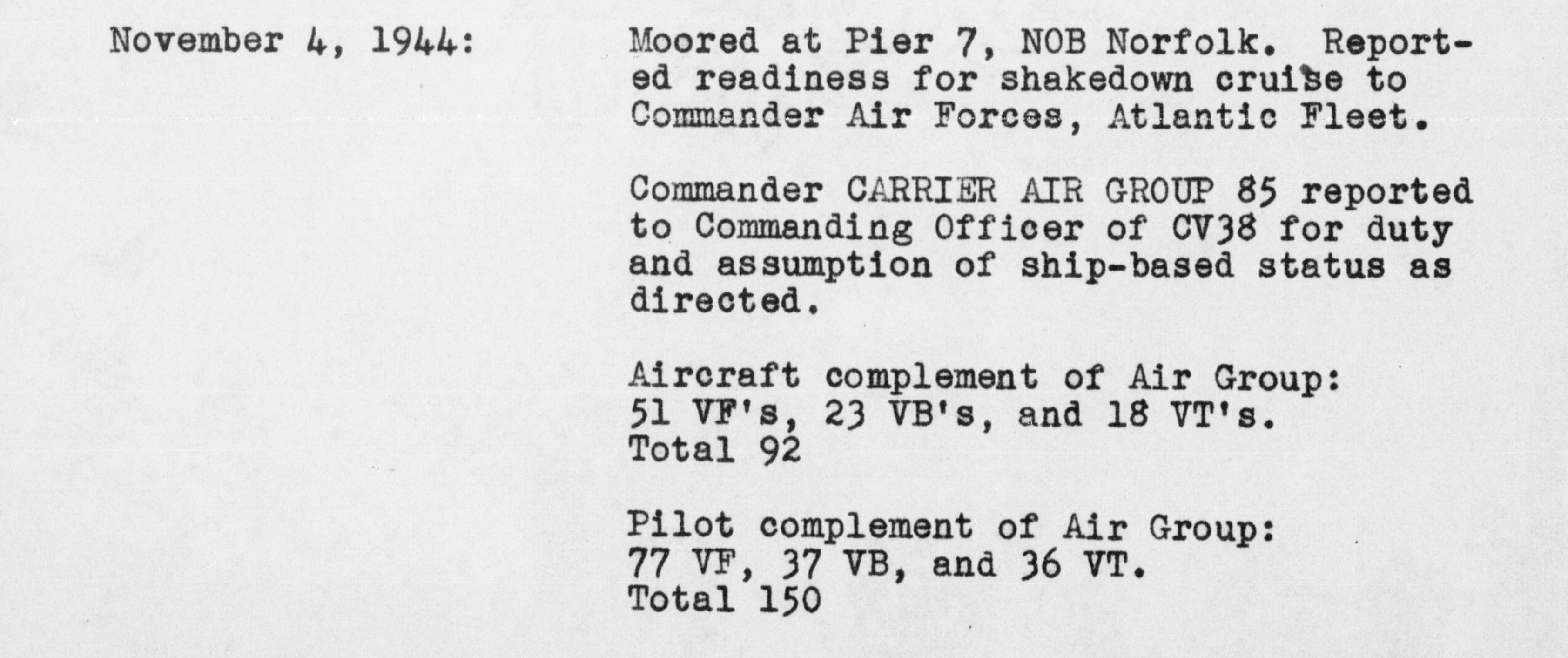

On 4 November, the 150 pilots of Carrier Air Group 85 reported for duty with an air group that included 51 fighters from the “Sky Pirates” VF/VBF-85 (flying rare F4U-1C Corsairs–with four 20mm cannons– along with more standard machine gun-armed F4U-1Ds and FG-1Ds, as well as a handful of black-painted F6F-5N/P Hellcat night fighters) 23 SB2C-4 Helldiver dive bombers of VB-85, and 18 TBM-3 Avenger torpedo bombers of VT-85, a total of 92 aircraft for starters.

While her aircraft complement would swell to as many as 104 assigned airframes and contract down into the low 80s, this Corsair-heavy load would remain the template over the next year. CVG-85, with its “Z” identifier, would go to war on Shang, bound, like the Doolittle Raiders, for Tokyo.

Aerial bow view of USS Shangri La (CV 38), taken by Navy Utility Squadron VJ-4 flying out of NAS Norfolk, 12 November 1944. 80-G-272499

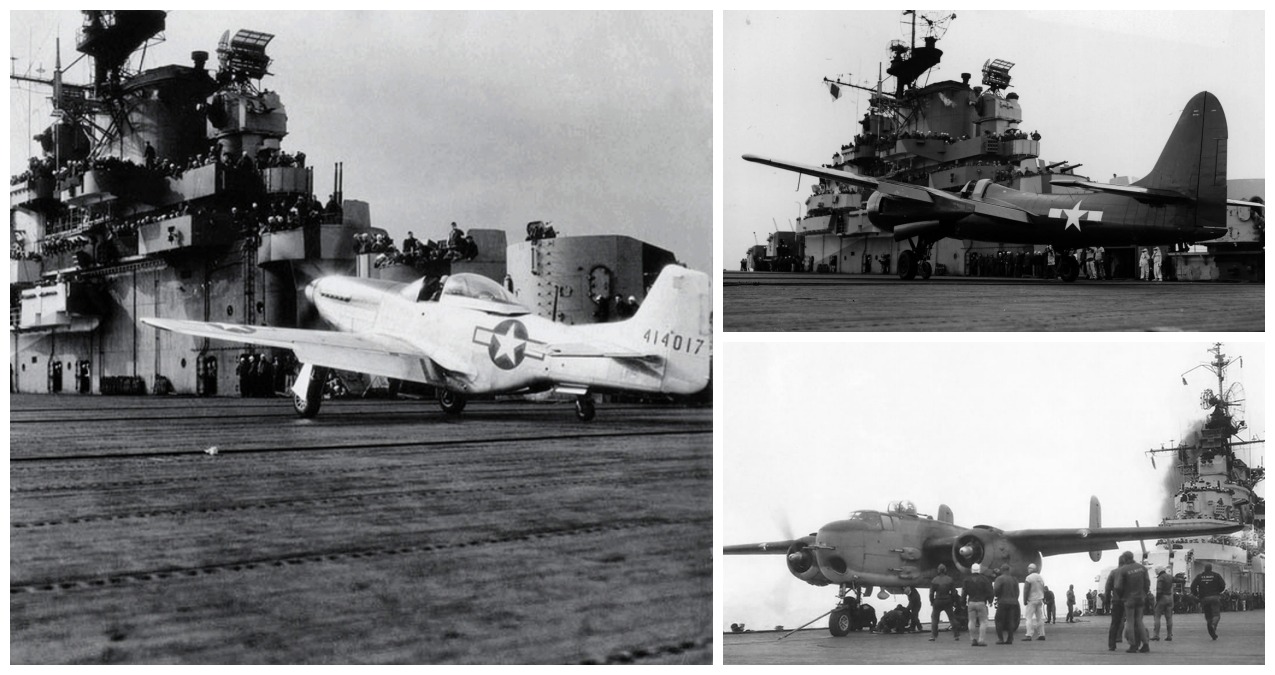

“Shang” quickly made naval aviation history by hosting three “firsts.” This included launching and trapping the Project Seahorse P-51D-5-NA Mustang, #44-14017, redesignated EFT-51D; along with the initial carrier trials for the Grumman F7F Tigercat and a North American PBJ-1H Mitchell patrol bomber– the latter a B-25H medium bomber modified for flattop operations in the truest Doolittle fashion.

In January 1945, as part of a three-ship group including the battlecruiser large cruiser USS Guam (CB-2) and the destroyer USS Harry E. Hubbard (DD-748), she sailed from Hampton Roads to San Diego via the Ditch and, after picking up passengers and extra planes, arrived at Pearl Harbor in mid-February to begin qualifying her aviators.

On 10 April 1945, she weighed anchor for Ulithi Atoll, and soon joined Task Group (TG) 58.4, launching her first airstrikes against Japanese assets on Okino Daito Jima, southeast of Okinawa, on 25 April. While the war in Europe was only two weeks away from ending, the war in the Pacific was very much still ongoing.

HMAS Nizam (D15), an N-class destroyer of the Royal Australian Navy in the British Pacific Fleet, coming alongside Shangri-La during the Battle for Okinawa, late April 1945. The carrier has Vought F4U Corsairs lined up on the flight deck, with a comparably huge Avenger, top left, and a Hellcat, top right. Note the Sky Pirates’ lightning flash insignia on the planes. Photo from the Hobbs Collection, a British album presentation to the RAN Archives.

VADM John S. “Slim” McCain hoisted his flag in Shangri-La on 18 May, and she became the flagship of his famed TF 38, heading for strikes against the Japanese home islands in June. alternating between close air support duty over Okinawa.

After a period off the lines, Shangri-La embarked, along with the other fast carriers of TF 38, on a month-long series of strikes starting in July along the Japanese coast in which what was left of the Imperial Japanese Navy was destroyed.

Via DANFS:

Shangri-La’s planes ranged the length of the island chain during these raids. On the 10th. they attacked Tokyo, the first raid there since the strikes of the previous February. On 14 and 15 July 1945, they pounded Honshu and Hokkaido and, on the 18th, returned to Tokyo, also bombing battleship Nagato, moored close to shore at Yokosuka. From 20 to 22 July, Shangri-La joined the logistics group for fuel, replacement aircraft, and mail. By the 24th, her pilots were attacking shipping in the vicinity of Kure. They returned the next day for a repeat performance, before departing for a two-day replenishment period on the 26th and 27th. On the following day, Shangri-La’s aircraft damaged cruiser Oyodo, and battleship Haruna, the latter so badly that she beached and flooded. She later had to be abandoned. They pummeled Tokyo again on 30 July, then cleared the area to replenish on 31 July and 1 August.

Air Raids on Japan, 1945. Japanese cruiser Tone under air attack near Kure, 24 July 1945. Photograph by USS Shangri-La (CV 38) aircraft. Note the camouflage nets hanging over its sides. The heavy cruiser settled to the bottom of the bay that day. 80-G-490148

Colorized photo of the above by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

Four days later…

Japanese battleship Hyuga sunk at Kure. Photographed by a USS Shangri-La (CV 38) aircraft on 28 July 1945. National Archives photograph: 80-G-490227.

Japanese light cruiser Ōyodo under air attack near Kure, 28 July 1945. Photo by USS Shangri La (CV 38), likely from one of her F6Fs. The cruiser capsized later that day, taking 300 men to the bottom with her. 80-G-490225

Shangri-La sent her CVB-85 planes to strike the airfields around Tokyo on the morning of 15 August 1945, but Japan’s capitulation was announced, and the fleet was ordered to cease hostilities.

The Final Touch: men add the last strikes to Shangri-La’s island scoreboard, August 1945. From the cover of The Horizon, the ship’s paper, Vol. 1. No. 14. The name of the paper, naturally, is drawn from the Lost Horizon novel. Via the NNAM.

CVG-85s record:

Airborne aircraft destroyed 10; damaged 8.

Planes on ground destroyed 120; damaged 129

Ships destroyed 24, tonnage 43,900 tons; ships damaged 87, tonnage 194,900 tons.

Destroyed ships include BB Haruna. The squadron also participated in attacking BB Nagato, directing attacks against protecting AA batteries, thus contributing to the bombing attack of the ship by other squadrons (this Battleship not counted in totals listed).

Locomotives destroyed 21; damaged 4.

Miscellaneous destroyed buildings: Warehouses 2, Factories 1, Hangers 1; Miscellaneous damaged buildings: Warehouses 15, Power plants 2, Radio stations 2, Factories 4, Hangers 20, and R.R. tunnel 1.All told, CVG-85 fired 620,176 rounds of machine gun ammo, dropped 731 bombs, loosed 2,333 5-inch HVAR aerial rockets, and heaved 21 napalm bombs against the Empire.

Shangri-La steamed around just offshore from 15 to 23 August, patrolling the Honshu area on the latter date.

Operation Snapshot: Task Force 38, of the U.S. Third Fleet, maneuvering off the coast of Japan, 17 August 1945, two days after Japan agreed to surrender. Taken by a USS Shangri-La (CV-38) photographer. The aircraft carrier in the lower right is USS Wasp (CV-18). Also present in the formation are five other Essex class carriers, four light carriers, at least three battleships, plus several cruisers and destroyers. 80-G-278815

The planes that likely took the above: F6F-5P Hellcats of Fighting Squadron (VF) 85 off the carrier Shangri-La (CV 38) pictured in flight near Japan 17 August 1945. Note the “Z” tail code. NNAM

Between 23 August and 16 September, her planes sortied on missions of mercy, air-dropping supplies to Allied prisoners of war in Japan while keeping up with patrols over the defeated Empire.

The badly damaged Japanese battleship Nagato off Yokosuka Naval Air Station, Japan, as seen from the plane of USS Shangri La (CV 38). Photographed by Photographer’s Mate Second Class J. Guttoach, 26 August 1945. 80-G-343774

Aerial view of Tokyo, Japan, 26 August 1945. An SB2C-4 Helldiver of Navy Dive Bombing Squadron 85 (VB-85), Air Group 85, flies in the foreground. Photographed by Lieutenant G. D. Rogers from an aircraft based on USS Shangri-La (CV 38). 80-G-339354

On 27 September, while Shangri-La was in Tokyo Bay, CVG-85 was disestablished.

In all, the fighters of VBF-85 alone flew 10,233 flight hours accomplishing 2,274 sorties, from Shangri-La in their 10 months together, broken down as follows:

Okinawa Campaign; 4,977 hours and 1,106 sorties

Operations against the Japanese Empire: 3,656 hours and 914 sorties.

Occupation of the Japanese Empire after the war before leaving 1,016 hours and 254 sorties.

CVG-8 would see nine fatalities during its relationship with Shangri-La, which, considering the tempo and heavy action, should be considered mercifully light.

Milo G. Parker, Ensign

Walter J. Barschat, Ensign

Charles W.S. Hullund, Lt. JG

William H. Marr, Lt. JG

John H. Schroff, Lt.

Sigurd Lovdal, Lt.

John S. Weeks, Lt. JG

Joseph G. Hjelstrom, Lt. JG

Richard T. Schaeffer, LCDR

Departing Japan on 2 October, Shangri-la sailed into San Pedro Bay on 27 October for three weeks of stateside R&R in the Long Beach area.

Navy Day, October 27, 1945. “Aloha” is spelled out by men onboard USS Shangri-La (CV 38) upon its arrival in Los Angeles, California, on October 21, 1945. Navy Museum Lot 10625-10.

After a maintenance period at Bremerton, she began peacetime operations out of San Diego, mainly carrier landing quals, then shipped out for Bikini Atoll and related Central Pacific venues to serve as a support ship for the Crossroads series of atomic tests.

USS Shangri-La (CV-38) underway in the Pacific during Crossroads, with her crew, paraded on the flight deck, 17 August 1946. Note the use of the letter Z on the flight deck instead of her hull number (38). 80-G-278827

Shangri-La was decommissioned and placed in the Reserve Fleet at San Francisco on 7 November 1947.

Her initial career lasted 1,148 days during which she earned two battlestars for her World War II service. For more details about the latter, her 238-page well-written War History is digitized and available online in the National Archives.

A second career

When the fireworks show kicked off in Korea, the Navy suddenly needed more carriers again. Shangri-La recommissioned on 10 May 1951 and was sent to the East Coast to serve primarily as a training carrier, conducting operations out of Boston. It was during this time that her designation changed to attack carrier (CVA) although she did very little attacking of anything during the Korean conflict.

Period press photo shows a near-empty Shangri-La conducting a washdown drill off Boston, 7 July 1952, an Atomic-era reality.

With the future of naval aviation based on jets rather than Corsairs, Helldivers, and Avengers, Shang decommissioned again on 14 November 1952, for a two-year $7 million SCB-125/SCB-27C modernization at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.

Her second period in commission only lasted 554 days.

Third time’s the charm

A rebuilt Shangri-La was recommissioned in January 1955.

“USS Shangri-La (CVA 38) was the first U.S. Navy attack carrier to embody all the latest improvements that are being made in the class carrier. These improvements include steam catapults, high capacity arresting gear, angled deck, enclosed bow, increased full capacity, and a tractor ramp around the outside of the “island” that will speed up aircraft spotting, April 27, 1955.” USN 663088.

This enabled her to carry and operate a new generation of combat aircraft that the designers of the Essex class could hardly envision in 1940.

An undated image of some of Shangri-La’s airwing by J R Eyerman in the LIFE archives. Note the early Vought F7U Cutlass, S-2 Tracker, F9F and HUP-2

USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) at sea, launching F9F Cougar fighters of ATG-3, 10 January 1956. Note steam rising from her port catapult. Photographed by B.W. Kortge. NH 75661

A North American AJ-2 Savage of Heavy Attack Squadron (VAH) 6 launches off the newly installed angled deck of the carrier Shangri-La (CVA 38) on February 24, 1956. A 25-ton medium bomber powered by two-piston engines and a J33-A-10 turbojet in the rear, the Savage could make 400 knots and carry six tons of bombs– as much as six of Doolittle’s B-25s– or a 1 Mark 4 nuclear bomb. Note that it was far heavier than the 18-ton B-25s used by Doolittle’s Raiders and had a wingspan some eight feet longer. Via NNAM.

USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) conducts the first successful at-sea cat shot of the enormous A3D Skywarrior of Heavy Attack Squadron (VAH) 1 “Smoking Tigers” flown by Dick Davidson on 1 September 1956, off Baja. As with the Savage, the Skywarrior (or Whale in common parlance) was larger than the WWII-era B-25 with a 35-ton maximum cat weight, 74-foot length (vs. 52 on the B-25H), and 72-foot wingspan (67 on the B-25H). U.S. Navy Photo via Navsource

Overhead view of a pair of F4D-1 Skyrays of Fighter Squadron (VF) 13 off the carrier Shangri-La (CVA 38) in flight in 1961. The AK code would make them from Carrier Air Group Ten (CAG-10) .The Navy only operated the Skyray from 1956-1964. It was the first Navy fighter that could exceed Mach 1 in level flight. NNAM.

Overhead photograph showing A4D Skyhawks of Attack Squadron (VA) 106 in flight over the carrier Shangri-La (CVA 38) on May 25, 1961. Future Apollo 17 commander astronaut Capt. Eugene Cernan spent time flying A4D Skyhawks in Attack Squadron (VA) 113, the “Stingers,” from Shangri-La in 1958. He was the final human to stand on the lunar surface and set the unofficial lunar land speed record in the rover. Photo via NNAM.

Her 1962 Med cruise, with CVG-10 embarked– VF-13 Night Cappers (F4D-1 Skyray), VMF-251 Thunderbolts (F8U-1E Crusader), VA-46 Clansmen and VA-106 Gladiators (A4D-2 Skyhawk), VA-176 Thunderbolts (AD-5 and AD-6 Skyraider), a det from VFP-62 Fighting Photos (F8U-1P Crusader), a det from VAW-12 Bats (WF-2 Tracer), and a det from HU-2 Fleet Angels (HUP-2 Retriever and Sikorsky HUS-1 Seahorse)– was the focus of a beautiful technicolor film entitled Flying Clipper, narrated by Burl Ives.

Based in San Diego from 1956 to 1960, she conducted regular WestPac cruises until her homeport shifted to Mayport, Florida, where she transitioned to NATO operations and deployments in the North Atlantic and Med under the Second and Sixth Fleet, respectively for the next decade.

USS Shangri-La (CVA-38), foreground, and USS Enterprise (CVAN-65) at Souda Bay, Crete, on 28 February 1964. In the right distance is an Albany class cruiser

Four F8U crusaders of VF-62 passing over USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) during Mediterranean cruise 1967-68. Note the AJ tail code of Carrier Air Wing 8. NH 71869

An F-8 Crusader of Fighter Squadron (VF) 13 with squadron XO Commander William Brandell, Jr., in the cockpit pictured before a catapult launch from the carrier Shangri-La (CVA 38) on May 1, 1967, forty-six years ago today. Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Gale “Abe” Abresch holds a sign he used to inform Brandell that he was about to make the 46,000th launch from the starboard catapult on board the ship. Petty Officers Third Class Glenn Sturtevant and Alkivivaeis Diakowmakis hook the airplane onto the cat. Via NNAM

Vought F-8C Crusader jet fighter (Bureau # 146956, possibly after conversion to an F-8K) In-flight over USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) in December 1968. Note the AJ of CVW-8. NH 71870

An RF-8G Crusader of Light Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron (VFP) 63 (BuNo. 146895) pictured in flight over the carrier Shangri-La (CVA 38) 28 July 1968. Note the AJ tail code of Carrier Air Wing 8 rather than VFP-63’s more common “PP” unit code.

USS Independence (CVA-62), a Forrestal-class supercarrier, along with the much smaller USS Shangri-La in 1968 celebrating 20 years of combat jets in naval aviation.

London Calling?

The endgame

With Shang still in U.S. service, on 30 June 1969, she was redesignated an antisubmarine warfare support aircraft carrier (CVS-38) a common and simple conversion that most of her remaining class underwent which shifted their air wings from high-performance fighters and strike aircraft like the F-8 and A-4 to more sedate ASW sub-busters like the turboprop S-2 Tracker and SH-3 Sea King helicopter.

Ironically, Shang never actually served as a proper CVS and was instead tasked as something of a “limited attack carrier” for a cruise off Vietnam the next year, her first combat since 1945.

With CVG-85 a memory some 25 years in the past, she went off to war carrying a mix of A-4C/E Skyhawks of VA-12, VA152, and VA-172; F-8H Crusaders of VF-111 and VF-162; a det of RF-8G Photo Crusaders from VFP-63, a det of UH-2C Sea Sprites from HC-2, and another det of E-1B Trackers (Stoof with a Roof) from VAW-121 as part of Carrier Air Wing Eight. CVW-8, with 169 officers and 873 enlisted, was assigned to Shang from 5 March to 17 December 1970 and would be her last embarked air wing.

USS Shangri-La (CVS-38) cruises toward Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, on 11 February 1970 on the eve of her Vietnam deployment. Official U.S. Navy Photograph (# K-81800).

Leaving Mayport in March, she set out via the South Atlantic and Indian oceans for Southeast Asian waters. As her combat report for the cruise mentions, “On 11 March, hundreds of timorous polliwogs were vigorously initiated into the Royal Domain of King Neptune by the Shangri-La’s cadre of sadistic shellbacks.”

Arriving in April, she would alternate stints on Yankee Station with rotations off the line to give her crew downtime in Hong Kong and Subic Bay. Shangri-La was also the only large American carrier to enter port in South Vietnam– arriving at DaNang on the night of 21 June to pick up parts for a broken elevator and returning to Yankee Station the same day. She would also suffer a sheared shaft coupling on No. 1 screw, a ruptured fire main that damaged most of her refrigeration areas, a minor deck fire, and a small engineering fire while underway. Combat deployments for a 26-year-old ship can be tough.

She earned three battle stars for her service in the Vietnam War and would make 12,691 launches and 11,994 recoveries from her deck during the deployment with CVW-8 embarking on 900 strike missions.

Shangri-La suffered eight fatalities through a mixture of enemy action and accidents on her 1970 cruise.

Arriving back at Mayport on 16 December to “maximum liberty” via the East Pacific, she had crossed the International Date Line and rounded Cape Horn to circumnavigate the globe.

After pre-inactivation overhaul at the Boston Naval Shipyard South Annex, Shangri-La decommissioned on 30 July 1971. She was placed in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet and berthed at Philadelphia. Her third and final period in commission lasted just over 16 years.

Wasting away

Jane’s 1974-75 entry on the seven remaining Essex carriers (listed as Hancock-class at the time) considered either in reserve while in mothballs or on active duty (Lexington, AVT-17).

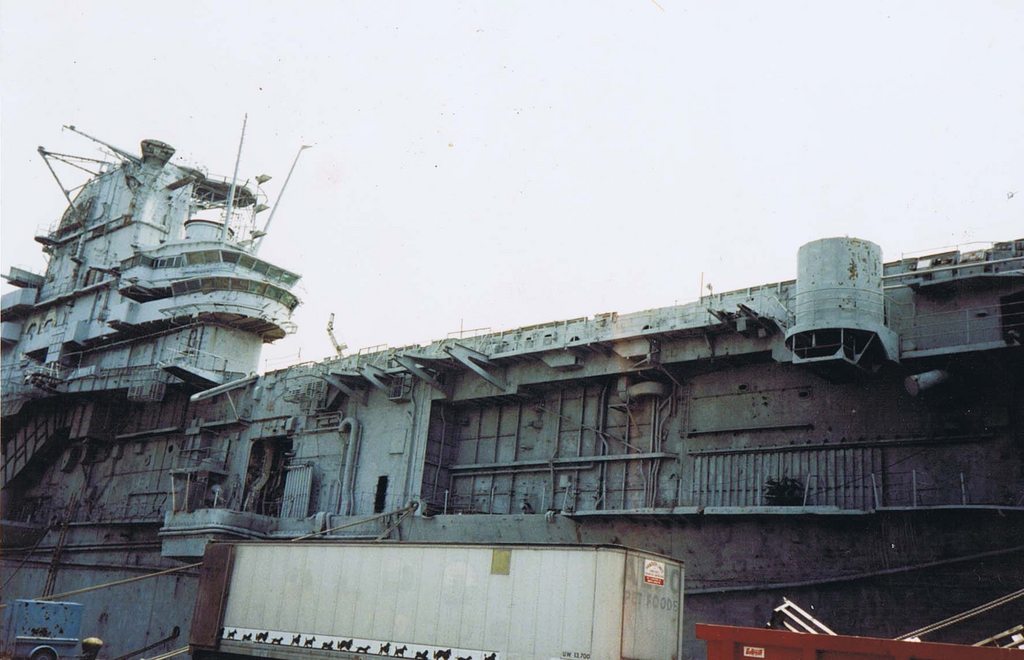

Shang was one of the last Essex-class carriers in mothballs and it was spitballed to recommission her (or one of her class) for a fourth time to assist in fleshing out the Reagan-Lehman “600 Ship Navy” to take on the Soviet Red Banner Fleet. However, all the laid-up WWII-period flattops were found to be in exceptionally poor shape although some had only been on red lead row for less than a decade. With grass growing on their decks, they were soon pulled out of floating storage and disposed of instead. As a result, she was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 15 July 1982.

While various groups planned to obtain Shangri-La for use as a museum ship, they all fell through, and on 17 June 1988, ex-Shangri-La was sold to the Lung Ching Steel Enterprise, Ltd., of Taiwan where she was towed for breaking that was completed the following year. The recycled steel of the old girl has likely been coming back home in small bits and pieces via household goods imported from Asia for decades.

Across her almost 44 years afloat, she spent just over 21 of them on active duty with the fleet.

Epilogue

As always, a ton of information on Shang is at your fingertips online at the National Archives.

There is a very active USS Shangri-La Reunion Association for Veterans of the carrier.

She is also remembered in maritime art.

Coming Home to Roost by R.G. Smith, showing A-4Cs headed back to USS Shangri La while on Yankee Station

As well as in scale model format.

While the carrier was turned to razor blades long ago, there are elements and monuments to the vessel scattered about the country. For instance, there is a USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) Room aboard the USS Hornet Museum, her sistership, docked at the former NAS Alameda. One of her 25-ton props is in the parking lot of Meding & Son Seafood, a restaurant off Hwy 1 in Delaware.

Her bell, recovered from a Florida scrapyard and restored in 2017, was initially presented to the NROTC unit at Jacksonville University and is now enshrined at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola next to a large scale model.

Also, NNAM has an RF-8G Photo Crusader (BuNo 14882) in their collection that flew with VFP-62 from the carrier and still carries her name.

NNAM’s Shangri-La Photo Crusader is on loan to the Frontiers of Flight Museum in Dallas.

During the Centennial of Naval Aviation celebration in 2010, at least one aircraft carried a throwback scheme that saluted Shangri-La, an EA-18G Growler (Bu No. 166899) of VAQ-129 “Vikings,” based at NAS Whidbey Island, wearing the same three-color blue as carried by CVG-85 during WWII. Like the “Sky Pirates” of VBF-85, the aircraft wore lightning bolts.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.