Happy 100 For U.S. Navy Carrier Air and what it Brings

While the Centennial of U.S. Naval Aviation — traditionally recognized as the moment Eugene B. Ely’s Curtiss pusher lifted off from USS Birmingham (Scout Cruiser # 2) in 1910– is a historic milestone that was passed over a decade ago, we are now in the Centennial of United States Navy Aircraft Carriers.

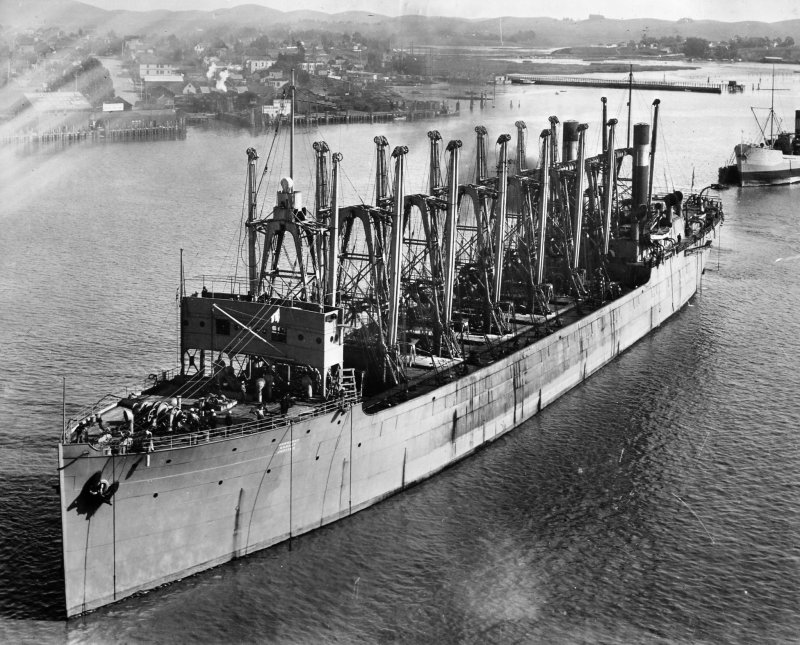

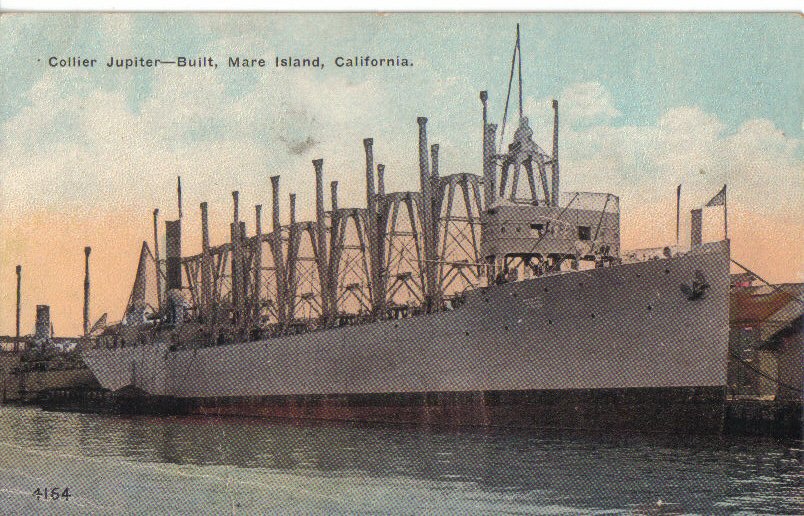

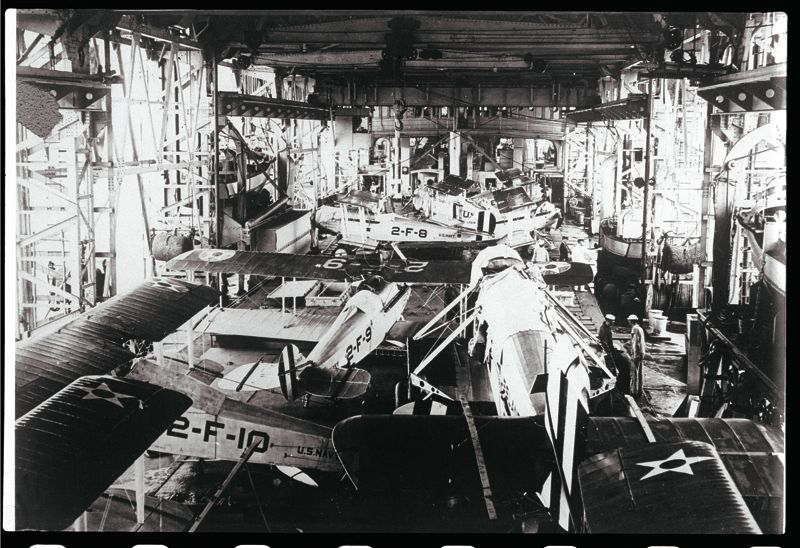

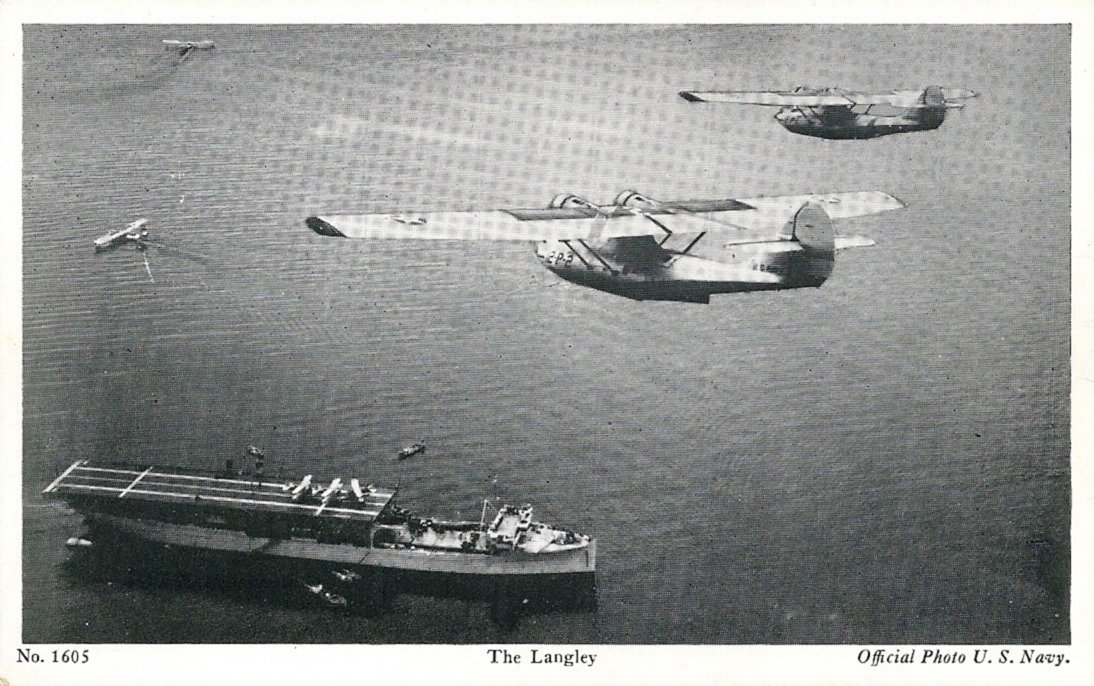

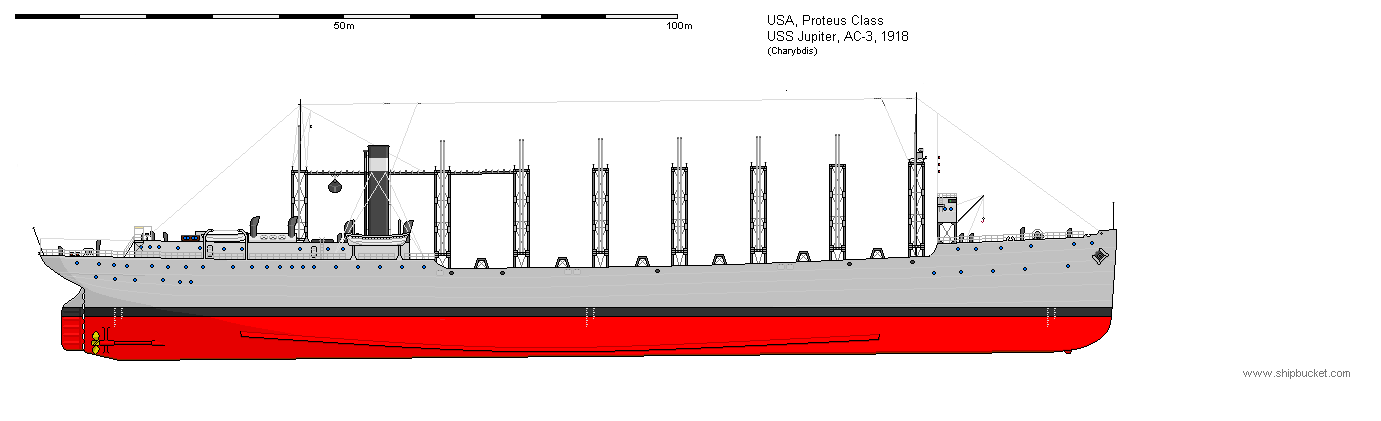

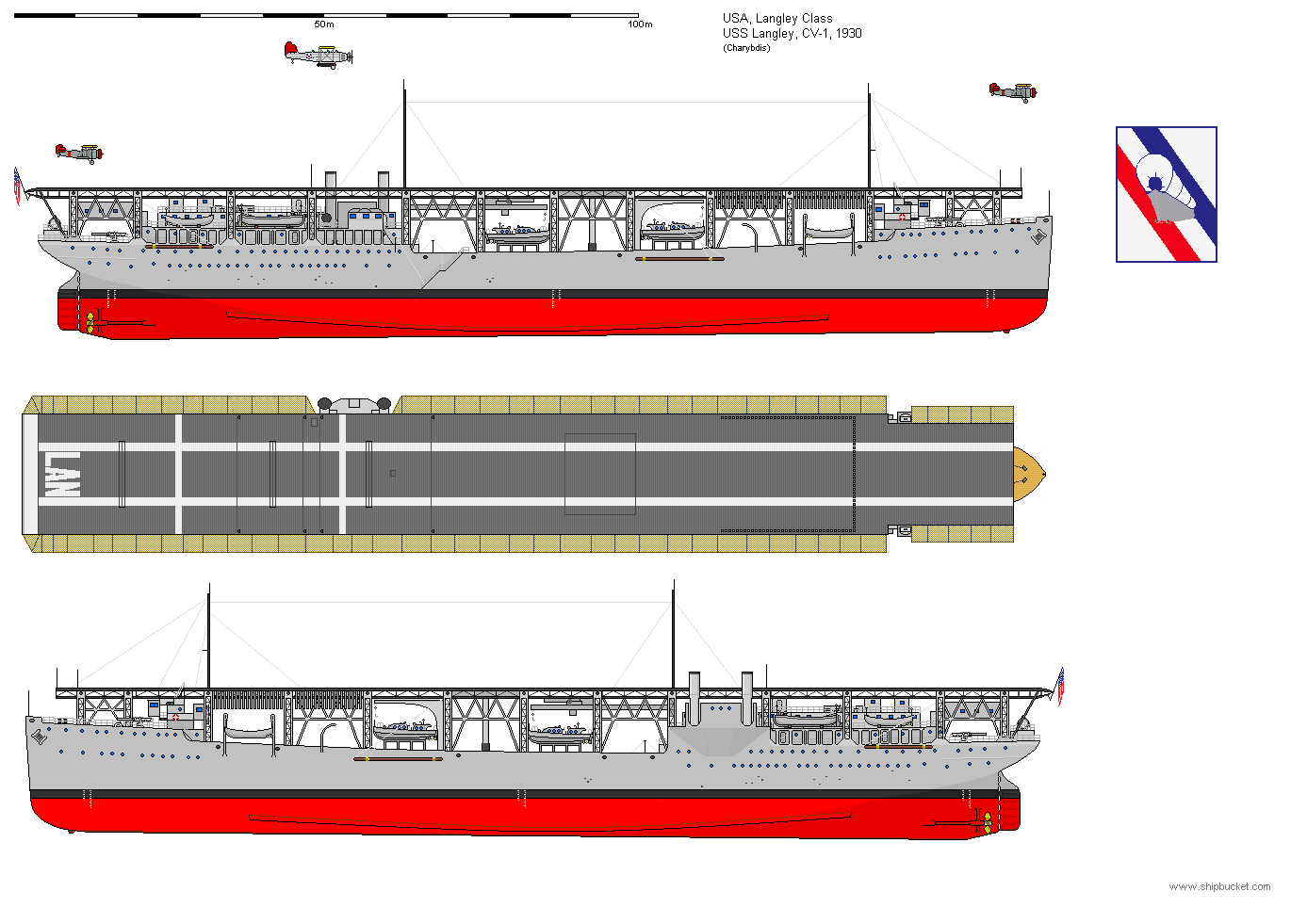

On 20 March 1922, following a two-year conversion at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, the former USS Jupiter (Navy Fleet Collier No. 3) was recommissioned as the United States Navy’s first aircraft carrier USS Langley (CV 1).

Named in honor of Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American aircraft pioneer, and engineer, “The Covered Wagon” started as an experimental platform but was quickly proven an invaluable weapons system that changed how the U.S. Navy fought at sea.

As noted by the Navy:

In the nearly 100 years since, from CV 1 to CVN 78, aircraft carriers have been the Navy’s preeminent power projection platform and have served the nation’s interest in times of war and peace. With an unequaled ability to provide warfighting capabilities across the full spectrum of conflict, and to adapt in an ever-changing world, aircraft carriers, their air wings, and associated strike groups are the foundation of US maritime strategy.

SECNAV Carlos Del Toro’s official message celebrating 100 years of U.S. Navy Carrier Aviation.

About those big decks…

Today, the U.S. Navy has more big deck flattops than any other fleet in the world– a title it has held since about 1943 or so without exception– including 10 beautiful Nimitz-class supercarriers (all of which have conducted combat operations) plus one Gerald R. Ford-class carrier in commission (and finally nearing her first deployment) and two more Fords building.

It is expected the Fords will replace the Nimitz class on a one-per-one basis. Of the current 10, five are in PIA, DPIA, or RCOH phases of deep maintenance, leaving just five capable of deployment. Still, even with half these big carriers tied down, the five large-deck CVNs on tap are capable of more combat sorties than every other non-U.S. flattop currently afloat combined.

For reference, check out this great series of top-down shots by MC3 Bela Chambers of the eighth Nimitz-class supercarrier USS Harry S Truman (CVN-75), the French aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle (R 91), and the Italian aircraft carrier ITS Cavour (C 550) transiting the Ionian Sea during recent NATO tri-carrier operations.

Commissioned in 1998, HST, like her sisters, is over 100,000-tons full load and is capable of carrying 90 fixed and rotary-wing aircraft. Currently embarked with CVW-1 aboard, you can see her deck filled with over 30 F-18E/Fs from VFA-11 (Red Rippers), VFA-211 (Fighting Checkmates), VFA-34 (Blue Blasters), VFA-81 (Sunliners), and EA-18Gs of VAQ-137 (Rooks) along with MH-60S/Rs of HSC-11 (Dragonslayers) and HMS-72 (Proud Warriors) and E-2D “Advanced” Hawkeyes of VAW-126 (Seahawks). The current wing is deployed with 46 F-18E/F, 5 EA-18G, 5 E-2Ds, 8 MH-60Ss and 11 MH-60Rs. Once an F-35C squadron gets integrated with CVW-1, replacing one of the Rhino units, it makes all sorts of other changes. Add to this MQ-25 Stingray drone refuelers and you see big things on the horizon.

For comparison, Charles de Gaulle, commissioned in 2001, is the only nuclear-powered carrier not operated by the U.S. Navy. At 42,000 tons she is smaller than the conventionally-powered Chinese carriers or the new Royal Navy QE2 class vessels, but the French have been operating her for two decades (off and on), including combat operations, and she is probably at this point the most capable foreign carrier afloat. However, she typically deploys with only around 30 aircraft, including the navalised Dassault Rafale (M model), American-built E-2C Hawkeyes, and a mix of a half-dozen light and medium helicopters. Her current “Clemenceau 22” deployment includes just 20 F3R Rafales of 12F and 17F.

The newest of the three vessels seen here, is the Italian aircraft carrier ITS Cavour (C 550), commissioned in 2008. Some 30,000-tons full load, she was built with lessons learned by the Italians after operating their much smaller (14,000-ton) “Harrier Carrier” Giuseppe Garibaldi, which joined the Marina Militare in 1985. Whereas Garibaldi was able to carry up to 18 aircraft, a mix of helicopters and Harriers, Cavour was designed for STOVL fixed-wing use with 10 F-35Bs (which Italy is slowly fielding) and a dozen big Agusta AW101 (Merlins). She is seen above with a quartet of aging Italian AV-8Bs, which explains why Garibaldi, currently in Norway on a NATO exercise there, is there sans Harriers.

It should be noted that, when talking about smaller but capable carriers such as Charles de Gaulle and Cavour, the U.S. Navy also has a fleet of “non-carriers” that can clock in for such power projection as well.

Further, there are seven remaining Wasp-class and two America-class amphibious assault ships, which can be used as a light carrier of sorts, filled with up to 20 AV-8Bs or F-35Bs (after updates), with the latter concept termed a “Lightning Carrier.” A slow vessel, these ‘phibs are not main battle force ships, and they cannot generate triple digits of sorties per day, but they are a powerful force multiplier, especially if they free up a big deck carrier for heavier work. While not as beefy or well-rounded an airwing as a Nimitz or (hopefully) Ford-class supercarrier, these LHD/LHA sea control ships can provide a lot of projection if needed– providing there are enough F-35Bs to fill their decks.

Thirteen U.S. Marine Corps F-35B Lightning II with Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 122, Marine Aircraft Group 13, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW), are staged aboard the amphibious assault ship USS America (LHA 6) as part of routine training in the eastern Pacific, Oct. 8, 2019. (U.S. Marine Corps photo illustration by Lance Cpl. Juan Anaya)

Speaking of which, USS Tripoli (LHA-7), is set to fully test the Lightning Carrier concept next month, drawing 20 F-35Bs from VMX-1, VMFA-211, and VMFA-225.