Warship Wednesday, Oct. 21, 2020: The Kaiser’s Gorgon

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1946 time period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Oct. 21, 2020: The Kaiser’s Gorgon

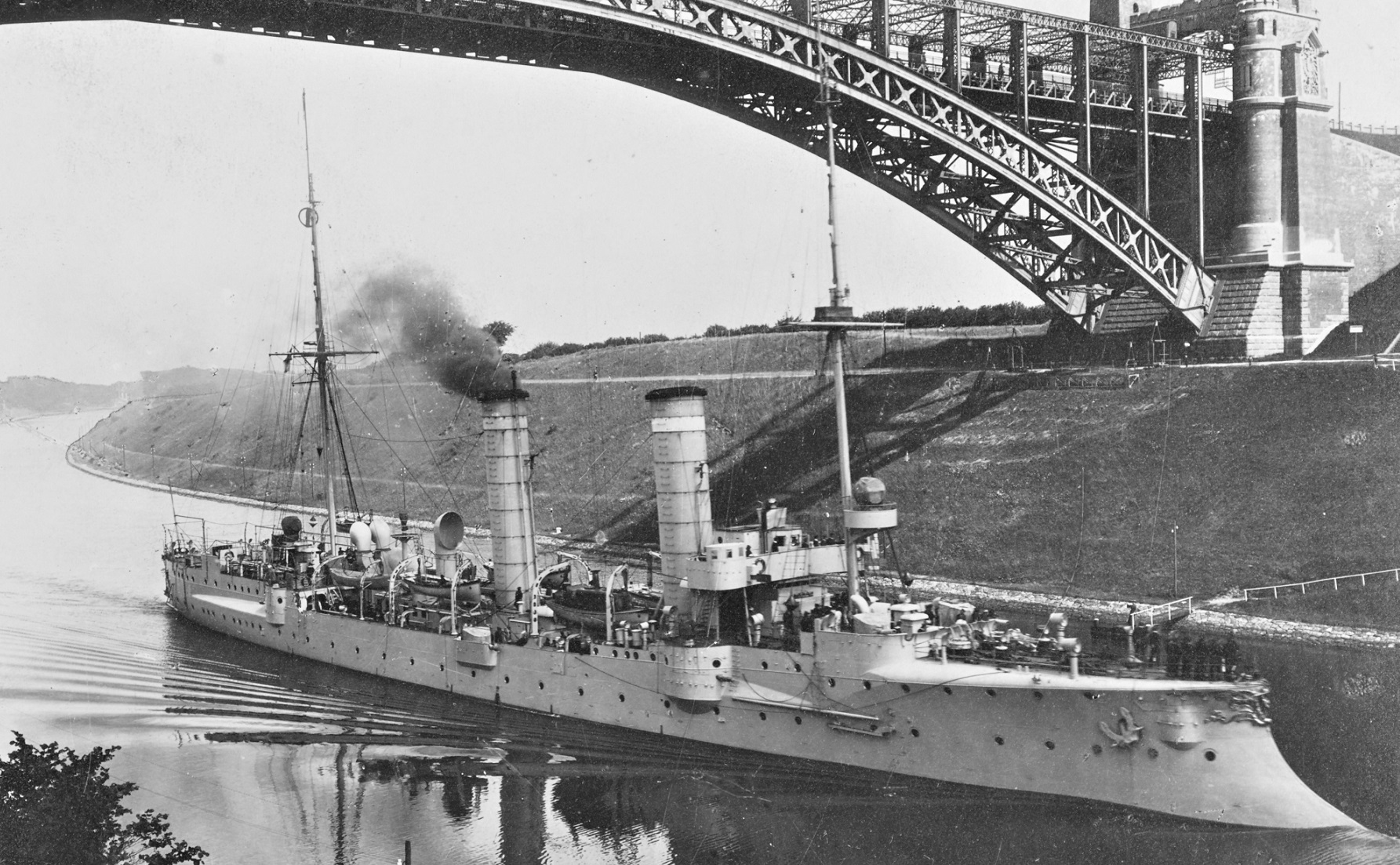

Here we see the Gazelle-class kleiner kreuzer SMS Medusa of the Kaiserliche Marine passing under the Levensauer Hochbrücke in the Kiel Canal, likely between 1901 and 1908. The sleek little vessel with beautiful lines and a prominent bow would go on to live a long life, a rarity for 20th Century Teutonic warships.

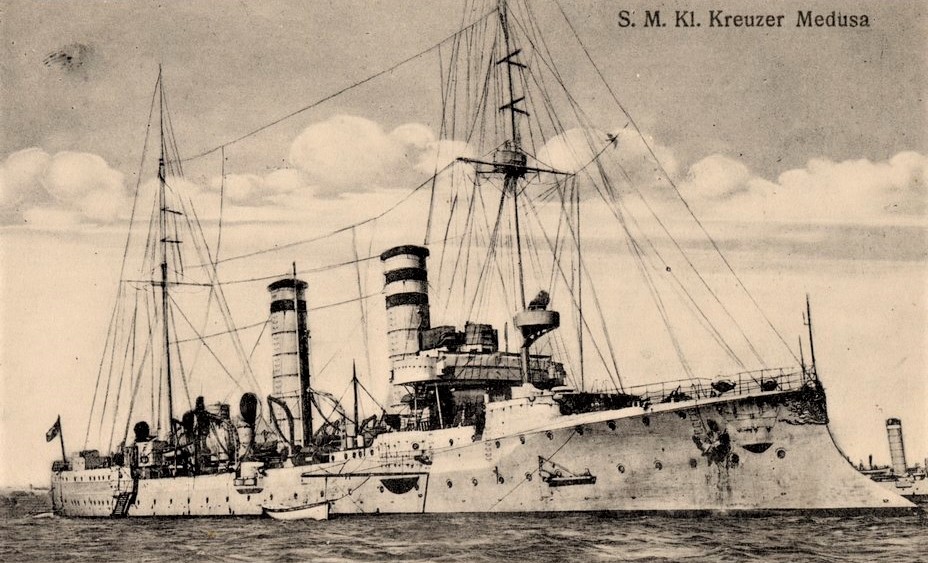

Medusa and her nine assorted sisters were built to scout for a growing battle fleet, and most importantly show the German flag around the world in ports both tropical and frozen. Just over 344-feet long, smaller today than a typical frigate, they were powered by two triple-expansion engines that gave the class a (planned) speed of 21.5-knots, which sounds slow by 21st Century standards but was fairly fast for ~1900.

Armed with ten 10.5 cm/40 (4.1″) SK L/40 naval guns and some torpedo tubes, they followed the traditional cruiser trope of being intended to sink anything faster than them and outrun anything bigger. She was built at AG Weser, Bremen for 4,739,000 Goldmarks and commissioned July 1901.

German light cruiser, either THETIS, ARIADNE, AMAZONE, or MEDUSA. Photo by Arthur Renard, Kiel, 1901. NH 47870

The 1914 Jane’s entry for the class. Of note, there were many small differences in dimensions, displacement, powerplant, and torpedo tube armament amongst the 10 vessels in the class. In a very real way, there could be considered at least three different flights among the Gazelles. Even Jane’s recognized this at the time, detailing Medusa not with a 10-ship Gazelle listing but with a five-ship subclass along with near-identical sisters Nymphe, Thetis, Ariadne, and Amazone.

Medusa spent her first decade on a series of flag-waving and training cruises around Europe, making just about every cherry port call you could want from Stockholm to Constantinople.

During this time, her gunners were considered the best in the fleet, winning the Kaiserpreis für Kleine Kreuzer, a feat that resulted in her becoming the fleet gunnery school ship for a period.

In May 1908, the still relatively young Medusa— as with most of her class– was overhauled and placed in reserve, tasked with second-line duties as larger, faster cruisers such as the Königsberg, Dresden, and Kolberg classes were joining the fleet.

Guns of August…

Nonetheless, when the Great War came, the Gazelles were reactivated and pressed into fleet service as scouts. In such work, they often tangled with much more powerful British vessels.

Medusa’s sistership, SMS Ariadne was sent to the bottom at Heligoland Bight on the fourth week of the war after she was caught between two of Beatty’s battlecruisers, while sister SMS Undine exploded after being hit by two torpedoes in 1915 and SMS Frauenlob was lost at Jutland opposing British cruisers as part of IV Scouting Group.

Medusa’s war service was more pedestrian, serving in a coast defense role along the Baltic to include being the flagship of Vizeadmiral Robert Mischke in the Küstenschutzdivision der Ostsee. She did see some action supporting German troops moving through Latvia in 1916 and ended the war as a tender to the old school frigate König Wilhelm in Flensburg.

Weimar Days

Post Versailles, the heart of the Kaiserliche Marine lay wrecked at Scapa Flow and the Allies took the better part of what remained afloat, leaving the newly-formed Weimar Republic’s Reichsmarine to rise like a phoenix with clipped wings from the ashes using obsolete vessels that London, Paris, and Washington neither wanted for their own fleets nor felt would be a threat.

When it came to the eight pre-dreadnoughts and six plodding cruisers allotted for the Germans to retain, ironically Medusa was the best of the lot and she served as the Reichsmarine’s first flagship from July 1920 through February 1921, when the duty was passed off to the battleship SMS Hannover, which by then was dusted off enough for active service.

To give her some better teeth, Medusa’s 450mm torpedo tubes were upgraded with larger 500mm tubes and she was fitted with rails to carry as many as 200 sea mines. The new Republic’s first active warship, Medusa cruised the Baltic in the summer of 1920, making Weimar Germany’s inaugural port calls in Finnish and Swedish harbors, a task she would repeat in 1924.

By March 1929, with the Reichsmarine able to add a few new K-class cruisers to the list as one-for-one replacements for their oldest boats, Medusa was disarmed and transferred to Wilhelmshaven to serve as a barracks ship. Her experienced crew changed hulls almost to a man to become plankowners on the brand-new German light cruiser Karlsruhe, the latter of which was known around Kiel as Ersatz Medusa during her building and outfitter.

Of her six sisters that survived the Great War, Gazelle was scrapped in poor shape in 1920, followed by SMS Nymphe and SMS Thetis which were scrapped in the early 1930s. Likewise, SMS Niobe was sold to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1925. Besides Medusa, the Germans only kept her sisters Arcona and Amazone, which, like our subject, were disarmed by the 1930s and hulked.

New war and a new look

As the Reichsmarine transitioned to the Kreigsmarine in 1935, and the world marched into war once again, Medusa swayed at her moorings until early 1940 when she was towed to Rickmers, Wesemünde, where she was reworked into a floating anti-aircraft battery, dubbed a flak kreuzer. She was not alone in this task as the Germans converted not only her sister Arcona in such a way but also a mix of seven captured Danish, Dutch, and Norwegian warships of similar vintage.

Medusa, her engine rooms gutted and funnels/masts removed, emerged with a new camouflage scheme and looked far and away different than when she was in the Kaiser’s service.

Her armament consisted of five 105/60 SK C/33 guns— good high-angle AAA weapons rated to 41,000 feet in altitude– as well as two 37mm flak guns, eight 20mm flak guns, HF/DF equipment, searchlights, a low-UHF band Würzburg gun-laying radar, and a Kleinkog fire control device, all state of the art for the time.

She would be crewed by the men of Marine Flak Abteilung 222 who not only manned Medusa but five other heavy batteries ashore as well.

Stationed typically at various roadsteads off Wilhelmshaven, Flak Batterie Medusa was frequently towed from anchorage to anchorage to minimize the risk of her being targeted specifically and, between 13 May 1940 and 3 May 1945, would sound her air raid alarm 789 times, sending up flak on at least 136 of those occasions. It should be noted that the Allies, primarily the British, carried out at least 102 air raids on the vital port, with 16 of those being large-scale attacks.

Note Medusa’s scoreboard, with numerous RAF and U.S. bomber outlines, none of which I can confirm. It should be recognized that the famous Flying Fortress, Memphis Belle (Boeing B-17F-10-BO #41-24485) was the recipient of flak while raiding Wilhelmshaven in 1943

Medusa remained afloat and fully operational until she was targeted by an airstrike on 19 April 1945 which killed 22 and seriously wounded 41 others. As the Allies were closing in on Wilhelmshaven, she was towed to the Wiesbaden Bridge and scuttled by her gunners there during the predawn hours of 3 May in an effort to block the channel. The city’s 33,000-man garrison, to include the former residents of Medusa, officially surrendered to Maj. Gen. Stanislaw Maczek’s 1st Polish Armored Division later the same day.

A local firm was granted salvage rights in 1947 and scrapped her wreck over the remainder of the decade.

When it comes to her two remaining sisters, they also proved fairly lucky in Kriegsmarine service. The unarmed ex-SMS Amazone was used post-war as an accommodation hulk for refugees and broken up in Hamburg in 1954 while Arcona, who like Medusa served as a floating AAA platform, was seized by the Royal Navy at Brunsbüttel in May 1945 and subsequently scrapped in 1949.

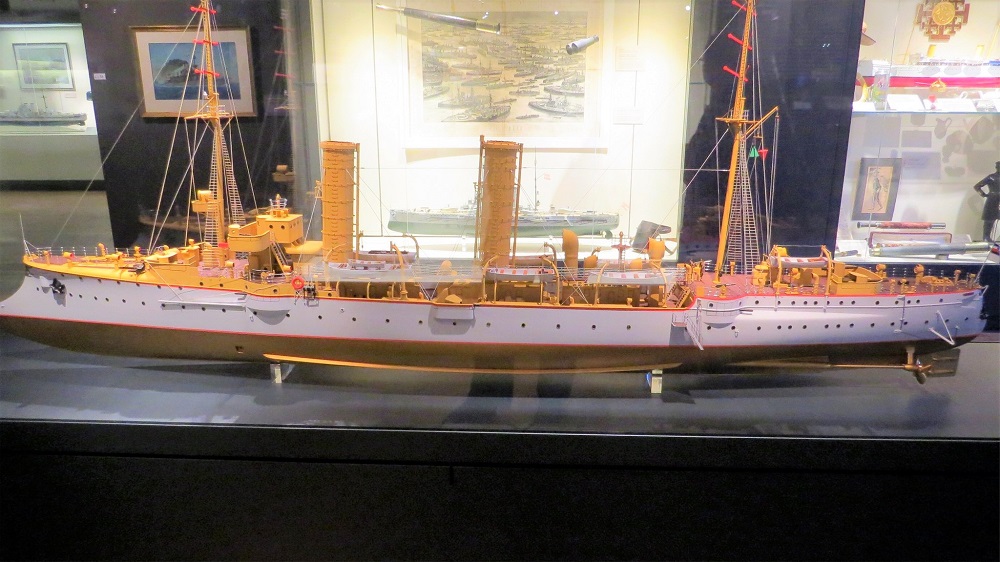

Today, Medusa is well-remembered in the model collection of the International Maritime Museum Hamburg, where both a circa 1900 white-hulled and a circa 1945 camouflage 1:100 scale example reside.

Speaking of models, Combrig offers an excellent 1:700 scale version of the Kaiser’s gorgon.

Those flak gunners lost on her decks in April 1945 are commemorated in a marker at Wilhelmshaven.

Specs:

(1900, Kleiner kreuzer)

Displacement: 2,659 tons normal; 3,082 full

Length: 344.8 ft overall; 328 waterline

Beam: 40 ft

Draft: 15.9 ft; 17.5 maximum

Propulsion: 9 x Schulz-Thornycroft water-tube boilers; 7,972 hp; two 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, two 3.5m props

Speed: 21.5 knots (designed), 20.9 knots in practice, 22 trials (all Gazelles were different in this)

Range: 3,560 nmi at 10 knots on 300 tons coal (560 tons max)

Complement: 14 officers, 243 enlisted men

Armor: (Sheathead & Muntz)

Deck: 25mm at ends, 50mm amidships

Conning tower 75-80 mm

Gun shields: 50 mm

Armament:

10 x 10.5 cm/40 (4.1″) SK L/40 (1,000 shells in magazine)

14 x 37mm 1-pounder Maxim Guns (autocannons)

2 x 45 cm (17.7 in) submerged beam tubes (5 torpedoes)

(1945, Flak kreuzer)

Displacement: 3,100 tons

Length: 344.8 ft overall

Beam: 40 ft

Draft: 15.9 ft

Propulsion: None, was towed and generators supplied on-board power while afloat

Armor: Deck: 20-50 mm, Conning tower 80 mm

Complement: 6 officers, 37 NCOs, 237 enlisted in embarked flak batteries and support personnel

Armament:

5 x 105/60 SK C/33 AAA guns

2 x 37mm Flak 36/37

8 x 20mm Flak 30

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!