Warship Wednesday, Aug. 10, 2022: Savo Pig Boat Avenger

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Aug. 11, 2022: Savo Pig Boat Avenger

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-33750

Above we see the bearded and very salty-looking crew of the S-42-class “Sugar Boat” USS S-44 (SS-155) manning the submarine’s 4″/50 cal Mark 9 wet-mount deck gun, circa January 1943. Note the assorted victory flags painted on the boat’s fairwater, she earned them.

The S-class submarines, derided as “pig boats” or “sugar boats.” were designed during the Great War, but none were finished in time for the conflict (S-1 was launched by the builders on 26 October 1918, just two weeks before the Armistice). Some 51 examples of these 1,000-ton diesel-electrics were built in several sub-variants by 1925 and they made up the backbone of the U.S. submarine fleet before the larger “fleet” type boats of the 1930s came online. While four were lost in training accidents, six were scrapped and another six transferred to the British in World War II, a lot of these elderly crafts saw service in the war, and seven were lost during the conflict.

The six boats of the S-42 subclass (SS-153 through SS-158) were slightly longer to enable them to carry a 4-inch (rather than 3-inch) deck gun with its own dedicated gun access hatch in the deck. Some 225 feet long overall, their submerged displacement touched 1,126 tons, making them some of the largest of the breed. Armed with four forward tubes (and no bow tubes), they had enough storage space to carry 10 21-inch torpedoes but were restricted in size to 16-foot long WWI-era fish as their tubes were shorter and couldn’t handle the newer 21-foot long Mark 14 torpedo which was introduced in 1931.

The Mark 10 of the 1920s, compared to the Mark 14, was slower and had shorter legs, but still carried a 500-pound warhead. The older torps were simple and dependable– provided you could get close enough to make them count.

It was thought the Sugar Boats, after testing, had enough fresh water for their crews and batteries to enable a patrol of about 25-30 days, and provision and diesel/lubricants for slightly longer.

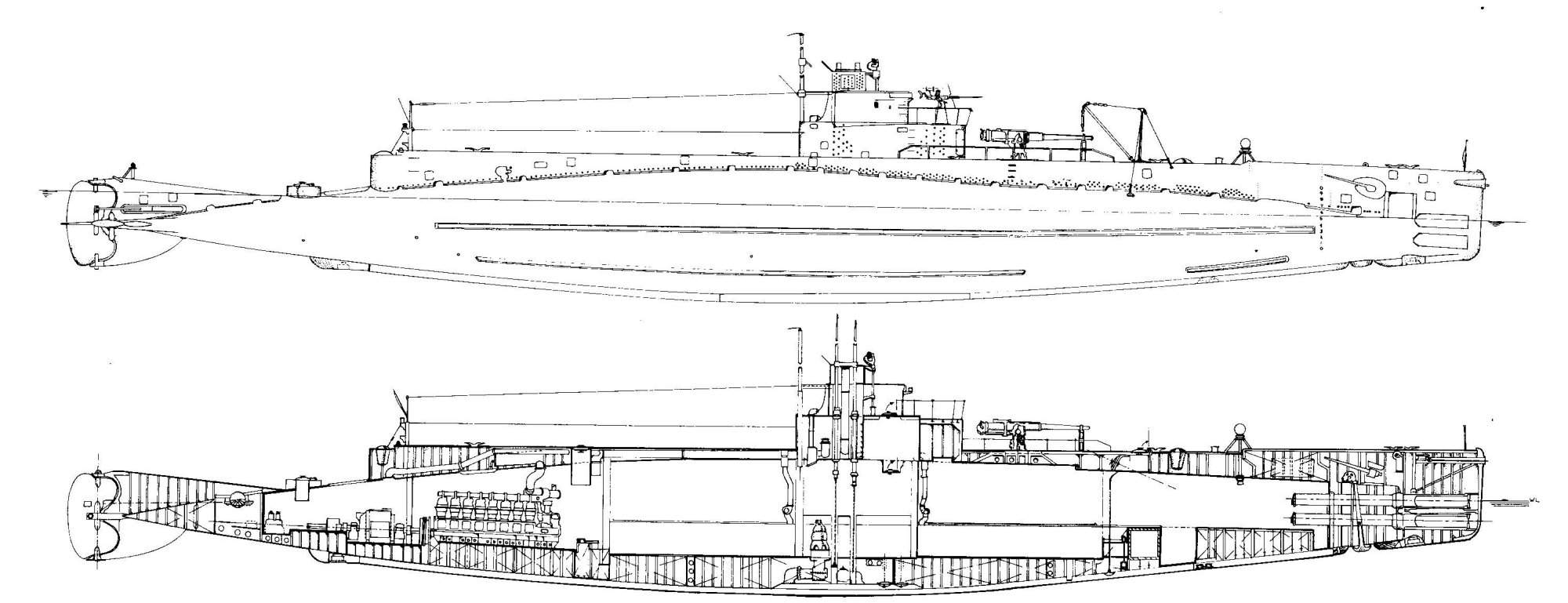

S-42 subclass. Drawing & Text courtesy of U.S. Submarines Through 1945, An Illustrated Design History by Norman Friedman. Naval Institute Press. Via Navsource

Referred to as the “2nd Electric Boat/Holland” type of the S-boat series, all six were built at Bethlehem’s Fore River yard.

Commissioned on 16 February 1925 (all six of the class were similarly commissioned inside 10 months across 1925-26) S-44 completed her shakedown in New England waters and then headed south for Submarine Division (SubDiv) 19, located in the Canal Zone, where she joined her sisters. For the next five years, homeported at Coco Solo, they ranged across assorted Caribbean, Pacific, and Latin American ports. This idyllic peacetime life continued through the 1930s as the Division’s homeport shifted to Pearl Harbor, then to San Diego, and back to Panama.

USS S-44 (SS-155) In San Diego harbor, California, during the later 1920s or the 1930s. Note how big her deck gun looks and her high-viz pennant numbers. NH 42263

USS S-44 (SS-155) Leaving Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, 1929. Photographed by Chief Quartermaster Peck. NH 42264

With the “winds of war” on the horizon and the realization that these small and aging boats may have to clock in for real, sisters S-42, S-44, and S-46 were sent to Philadelphia Naval Yard in early 1941 to be modernized. By August 1941, S-44 was on a series of shakedown/neutrality patrols along Cape Cod and Rhode Island, conducting mock torpedo runs on the destroyer USS Mustin (DD-413), a tin can that would go on to earn 13 battle stars in WWII. Still on the East Coast when news of the attack on Pearl Harbor hit, she soon got underway for Panama.

S-44’s principal wartime skipper, from October 1940 through September 1942, covering her first three War Patrols, was Tennessee-born LT. John Raymond “Dinty” Moore (USNA 1929).

While most Sugar Boats still in the fleet in 1942 were relegated to ASW training and new submariner school tasks as well as defense of the Panama Canal Zone and Alaska, some were made ready to go to the West Pac and get active in the war. Though small and armed with obsolete torpedoes, a handful of Sugars– our S-44 included– were rushed to block the Japanese progress in the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomon Islands, until larger and more capable Fleet Boats (Balao, Gato, Tench classes, etc.) could be sent to the area.

First Patrol

Assigned to SUBRON Five, S-44 got underway from Brisbane for her patrol area on 24 April 1942, she haunted the Cape St. George area of New Ireland in the Bismarck Archipelago for three weeks and reported a successful hit on a Japanese merchant of some 400 feet/4,000 tons on 12 May after a four-torpedo spread.

From Moore’s report:

Post-war, this was confirmed to be the Japanese repair ship Shoei Maru (5644 GRT) returning to Rabaul after coming to the assistance of the minelayer Okinoshima, sunk by S-44′s sistership S-42 earlier in the day. Talk about teamwork.

USS S-44 returned to Brisbane on 23 May, just shy of being out for a month.

Second Patrol

After a two-week refit and resupply, S-44 left Brisbane again on 7 June 1942– just after the Battle of Midway– ordered to patrol off Guadalcanal where local Coastwatchers reported a Japanese seaplane base to be under construction. There, she compared the coastline to old Admiralty charts of the area and watched for activity, noting fires and shipping traffic. Midway into the patrol, the Sugar boat fired three torpedoes at a 200-foot/2,000-ton freighter with “69” on the side of her bridge and one visible deck gun.

From Moore’s report:

This was post-war confirmed to be the Japanese auxiliary gunboat Keijo Maru (2626 GRT, built 1940) sent to the bottom about 12 nautical miles west of Gavutu, Solomon Islands.

As noted by DANFS:

The force of the explosion, the rain of debris, and the appearance and attack of a Japanese ASW plane forced S-44 down. At 1415, S-44 fired her torpedoes at the gunboat. At 1418, the enemy plane dropped a bomb which exploded close enough to bend the holding latch to the conning tower, allowing in 30 gallons of sea water; damaging the depth gauges, gyrocompass, and ice machine; and starting leaks. Her No. 1 periscope was thought to be damaged; but, when the submarine surfaced for repairs, a Japanese seaman’s coat was found wrapped around its head.

Two patrols, two kills under her belt, S-44 arrived back at Brisbane on 5 July.

Third Patrol

After three weeks of rest and airing out, S-44 headed North from Brisbane on 24 July, ordered to keep her eyes peeled off the New Britain/New Ireland area. After stalking a small convoy off Cape St. George in early August but unable to get a shot due to heavy seas, she began haunting the Japanese base at Kavieng Harbor on New Ireland. This, likewise, proved fruitless and she ranged the area until when, on the early morning of 10 August 1942 (80 years ago today), some 9,000 yards away, she sighted four enemy heavy cruisers steaming right for her.

What a sight it must have been!

Just 18 minutes later, having worked into a firing position for the oncoming column– over 30,000 tons of the Emperor’s bruisers in bright sunlight on a calm sea — S-44 fired all four tubes at the heavy bringing up the rear then dived deep to 130 feet. Four old reliable Mark 10s launched from just 700 yards did the trick.

Moore would later detail, “We were close enough to see the Japanese on the bridge using their glasses” and that the looming cruiser looked bigger than the Pentagon building. While submerged and listening, Moore would later say, “Evidently all her boilers blew up…You could hear hideous noises that sounded like steam hissing through the water. These noises were more terrifying to the crew than the actual depth charges that followed. It sounded as if giant chains were being dragged across our hull as if our own water and air lines were bursting.”

The details of action from Moore’s official report:

Post-war, it was confirmed this target was the Furutaka-class heavy cruiser HIJMS Kako, one of the four heavy cruisers of Cruiser Division 6 (along with Aoba, Furutaka, and Kinugasa) which just five hours before had jumped the Allied cruisers USS Astoria, Quincy, Vincennes, and HMAS Canberra off Savo Island, leaving all wrecks along Iron Bottom Sound. During that searchlight-lit surface action, Kako fired at least 192 8-inch, 124 4.7-inch, and 149 25-mm shells as well as ten Long Lance torpedoes, dealing much of the damage to the Allied vessels.

While Kako had received no damage at Savo, her meeting with S-44 was lopsided in the other sense.

As told by Combined Fleet:

The Kawanishi E7K2 “Alf” floatplane from AOBA, patrolling overhead, fails to send a timely warning and at 0708 three torpedoes hit KAKO in rapid succession. The first strikes to starboard abreast No. 1 turret. Water enters through open scuttles of the hull as the bow dips and twists further within three minutes of being hit. The other torpedoes hit amidships, in the vicinity of the forward magazines, and further aft, abreast boiler rooms Nos. 1 and 2. KAKO rolls over on her starboard side with white smoke and steam belching from her forward funnel. An enormous roar ensues as seawater reaches her boilers.

At 0712, the Japanese start depth charging the S-44, but without success. S-44 slips away.

At 0715, KAKO disappears bow first in the sea to the surprise and dismay of her squadron mates. She sinks off Simbari Island at 02-28S, 152-11E. Sixty-eight crewmen are killed, but Captain Takahashi and 649 of KAKO’s crew are rescued by AOBA, FURUTAKA and KINUGASA.

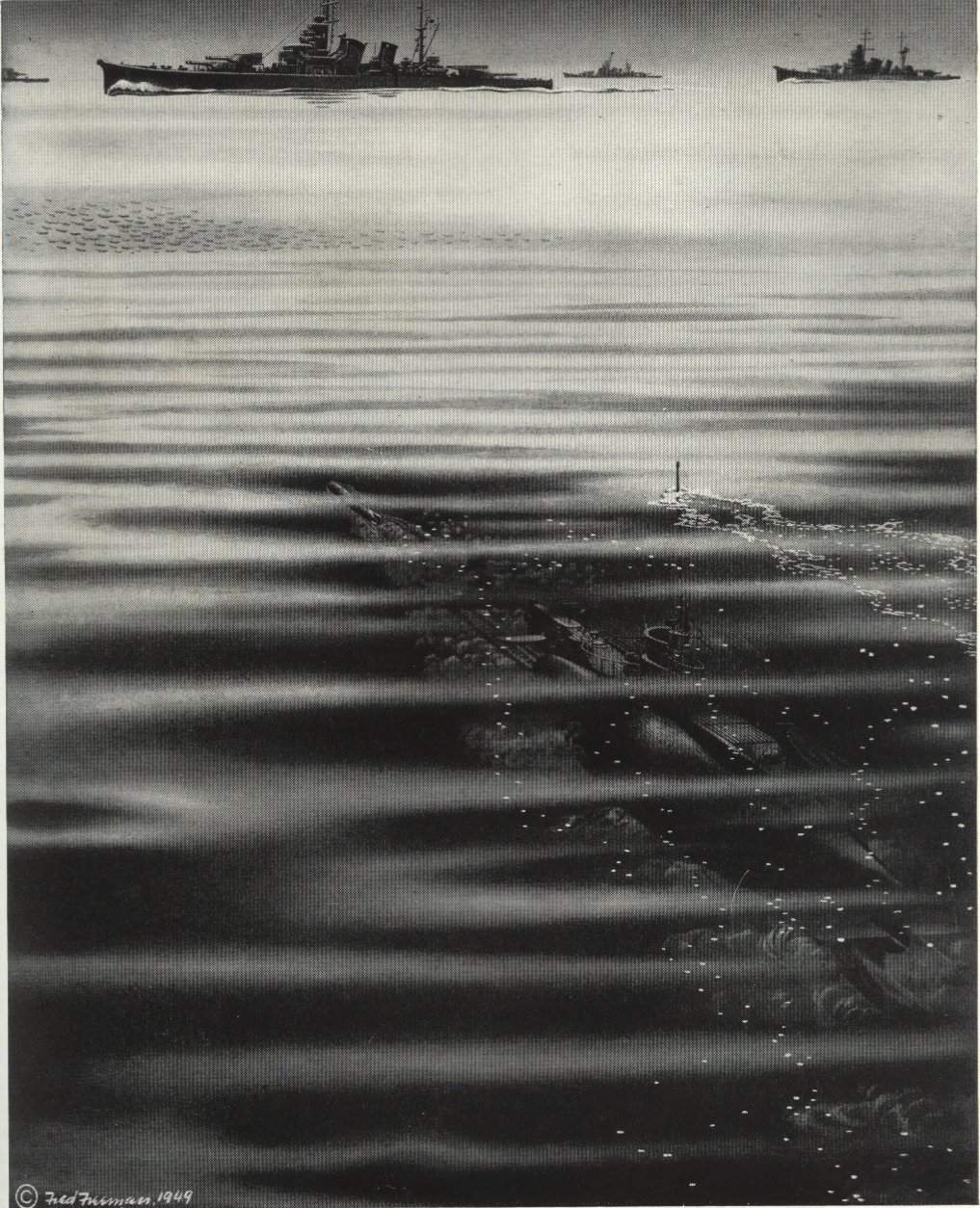

“The S-44 (SS-155), vs HIJMS Kako. Patrolling off New Ireland, the veteran S-boat ambushes the enemy cruiser division at the entrance to Kavieng Harbor. Four torpedoes (range 700 yards) send Kako to the bottom, an 8,800-ton warship sunk by an 850-ton sub. This sinking of the first Japanese heavy cruiser avenged the defeat at Savo Island.” Drawing by LCDR Fred Freemen, courtesy of Theodore Roscoe, from his book “U.S. Submarine Operations of WW II”, published by USNI. Original painting in the LOC.

S-44 returned to Brisbane, Australia, on 23 August 1942, where the sinking of Kako was a big deal for a Navy that had just suffered its worst night in history.

Truth be told, it was a big deal for the American Submarine Force as well.

In the first 245 days of the Pacific War, suffering from a mix of bad torpedoes (mostly the vaunted new Mark 14s) and timid leadership, U.S. subs had only accounted for nine rather minor Japanese warships, even though the Navy had no less than 56 boats in the Pacific at the beginning of the war and soon doubled that number:

- Submarine I-73, sunk by USS Gudgeon, 27 January 1942.

- Destroyer Natsushio, sunk by USS S-37, 9 February 1942.

- Seaplane carrier Mizuho, sunk by USS Drum, 2 May 1942.

- Minelayer Okinoshima, sunk by USS S-42, 11 May 1942.

- Submarine I-28, sunk by USS Tautog, 17 May 1942.

- Submarine I-64, sunk by USS Triton, 17 May 1942.

- Destroyer Yamakaze, sunk by USS Nautilus, 25 June 1942.

- Destroyer Nenohi, sunk by USS Triton, 4 July 1942.

- Destroyer Arare, sunk by USS Growler, 5 July 1942.

Indeed, by that time in the war, the Japanese had only lost one heavy cruiser, Mikuma, which was finished off by carrier aircraft at Midway after she was crippled in a collision with another ship.

So of course, Dinty Moore earned hearty congrats and would eventually pin on a Navy Cross for S-44s action against Kako.

Captain Ralph W. Christie, USN, Commander Task Force 42 and SUBRON5 (left) Congratulates LCDR John R. Moore, USN, skipper of USS S-44 (SS-155), as he returned to this South Pacific base after a very successful week of patrol activity. (Quoted from original World War II photo caption) The original caption date is 1 September 1942, which is presumably a release date. 80-G-12171

Fourth Patrol

Dinty Moore would leave his first command to take control of the more advanced Sargo-class boat USS Sailfish (SS-192) and S-44 would head back out from Brisbane on 17 September with LT Reuben Thornton Whitaker as her skipper.

Dogged by Japanese ASW patrols as well as a persistent oil leak and a battery compartment fire, S-44 returned to Australia on 14 October after a 4,262-mile patrol with nothing to add to her tally board despite a claimed attack on an Ashashio-class destroyer that was not borne out by post-war analysis.

The boat needed some work, that’s for sure. She had spent 150 of the past 220 days at sea, with 120 of that on war patrol. She leaked and had numerous deficiencies, all exacerbated by repeated Japanese depth charging. Her crew, which was largely original men that had shipped out with her from Philadelphia in 1941, had lost up to 25 pounds apiece, and nerves were frayed.

Refit

On 4 November 1942, with LT Whitaker sent on to the Gato-class fleet boat USS Flasher (SS-249), S-44 was sailed for the East Coast via the Panama Canal under the command of LT Francis Elwood Brown (USNA ’33) (former CO of USS S-39) and slowly poked along until she arrived at Philadelphia Navy Yard in April 1943.

USS S-44 (SS-155) Underway off the Panama Canal Zone, circa February 1943, while en route to the Philadelphia Navy Yard for overhaul. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives. 19-N-41382.

At PNSY, S-44 was reworked over the summer and picked up a 20mm Oerlikon as well as a JK passive sonar and SJ/ /SD radars.

USS S-44 (SS-155) Underway off the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania, after her last overhaul, on 11 June 1943. 19-N-46194

“S-44 (SS-155), was one of six E.B. boats extensively modernized during WW II. The refit included the installation of air conditioning, with the unit installed in the crew space abaft the control room, alongside the refrigerator. S-44 was fitted with radar (SJ forward, SD abaft the bridge), a loop antenna built into the periscope shears for underwater reception, & a free flooding structure carrying a 20-mm anti-aircraft gun, with a box for 4-in ready-service ammunition below it. A JK passive sonar, probably installed at Philadelphia during a refit between November & December 1941, was located on the forward deck. On the keel below it was a pair of oscillators.” Drawing by Jim Christley. Text courtesy of U.S. Submarines Through 1945, An Illustrated Design History by Norman Friedman. Naval Institute Press, via Navsource.

Fifth, and Final, Patrol

Departing PNSY on 14 June 1943, S-44 transited the Ditch once again and arrived at Dutch Harbor, Alaska on 16 September, with Brown still in command. After 10 days of making ready, S-44 sortied out past the Russian church on her 5th War Patrol on 26 September, bound for the Kuriles, where she never came back from, although two survivors eventually surfaced in 1945.

The story of what happened to her was only learned after VJ Day.

It is believed that S-44 was sunk east of the Kamchatka Peninsula by the Japanese Shimushu-class escort vessel Ishigaki.

As detailed by DANFS:

On the night of 7 October, she made radar contact with a “small merchantman” and closed in for a surface attack. Several hundred yards from the target, her deck gun fired and was answered by a salvo. The “small merchantman” was a destroyer. The order to dive was given, but S-44 failed to submerge. She took several hits, in the control room, in the forward battery room, and elsewhere.

S-44 was ordered abandoned. A pillowcase was put up from the forward battery room hatch as a flag of surrender, but the shelling continued.

Possibly eight men escaped from the submarine as she went down. Two, Chief Torpedoman’s Mate Ernest A. Duva and Radioman Third Class William F. Whitemore, were picked up by the destroyer. Taken initially to Paramushiro, then to the Naval Interrogation Camp at Ofuna, the two submariners spent the last year of World War II working in the Ashio copper mines. They were repatriated by the Allies at the end of the war.

Epilogue

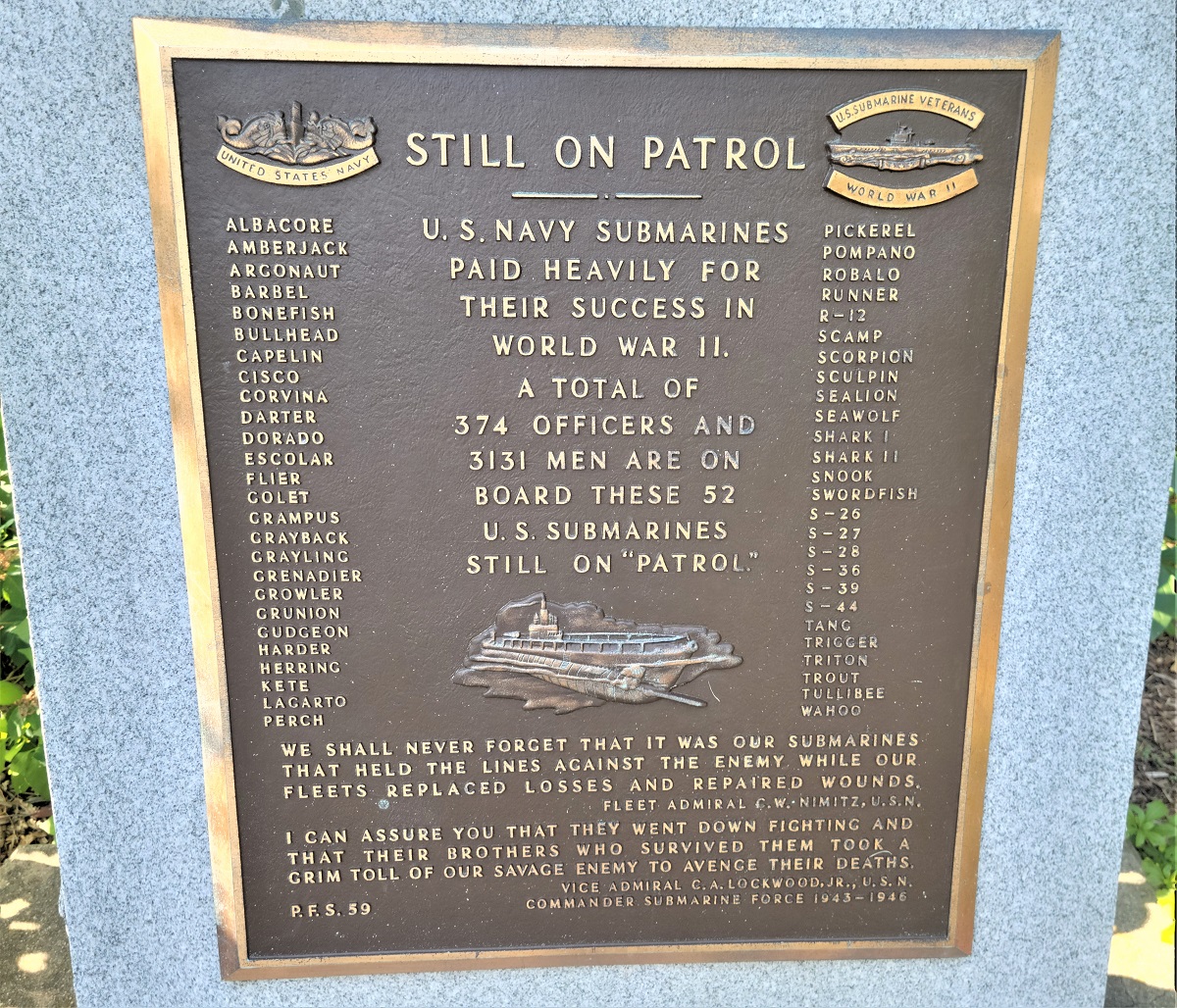

S-44 remains one of the Lost 52 U.S. submarines from WWII still regarded on eternal patrol.

S-44 was one of six Sugar Boats lost during WWII. Their names here are inscribed on a memorial at the USS Albacore Museum in New Hampshire. Similar memorials are located in all 50 states. (Photo: Chris Eger)

Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery USS S-44 memorial in Illinois, installed in 2003 by Members of U.S. Submarine Veterans of World War Two

Thus far, her wreck, believed off Paramushir (AKA Paramushiro or Paramushiru) Island, has not been located and as that windswept volcanic rock has been occupied by the Russians since August 1945, she likely will never be discovered.

S-44’s war records from August 1941 – October 1942, including her first four War Patrols, have been digitized and are in the National Archives. She earned two battle stars during World War II.

She was remembered in postal cachets on the 40th anniversary of her loss when the USPS issued an S-class submarine stamp in 2000, among others.

For what it is worth, her killer, the escort Ishigaki, was herself sent to the bottom by the American submarine USS Herring (SS-233) in May 1944.

S-44’s most famous skipper, Dinty Moore, would command Sailfish on that boat’s 6th, 7th, and 8th War Patrols, sinking the Japanese merchant Shinju Maru (3617 GRT) and the Japanese collier Iburi Maru (3291 GRT) in 1943. He would join Admiral Lockwood’s Roll of Honor in 1944 and ultimately retire as a rear admiral in 1958. The Navy Cross holder would pass at age 79 and is buried in Georgia.

Of S-44’s five Fore River-built EB-designed sisters, all survived the war and gave a full 20+ years of service in each case. They conducted over 25 patrols, mostly in the West Pac, and claimed a half dozen ships with class leader S-42 being the most successful (besides S-44) with the aforementioned minelayer Okinoshima confirmed as well as an attack on a destroyer logged. All these sisters were paid off just after the war and sold for scrapping or sunk as a target by the end of 1946.

None of the 51 Sugar Boats are preserved. Those ancient bathtubs held the line in ’42-43 during the darkest days of the Pacific War and proved their worth.

The Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee post-war attributed 201 Japanese sunken warships, totaling some 540,192 tons, to American submarines.

Specs:

Displacement: 906 tons surfaced; 1,126 tons submerged

Length: 216 feet wl, 225 feet 3 inches overall

Beam: 20 feet 9 inches

Draft: 16 feet (4.9 m)

Propulsion: 2 × NELSECO diesels, 600 hp each; 2 × Electro-Dynamic electric motors, 750 horsepower each; 120 cell Exide battery; two shafts.

Speed: 15 knots surfaced; 11 knots submerged

Bunkerage: 46,363 gal

Range: 5,000 nautical miles at 10 knots surfaced

Test depth: 200 ft.

Crew: 38 (later 42) officers and men

Armament (as built):

4 x 21 in (533 mm) torpedo tubes (bow, 10-12 torpedoes)

One 4″/50 deck gun

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!