Warship Wednesday, March 8, 2023: USS FBI

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 time period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, March 8, 2023: USS FBI

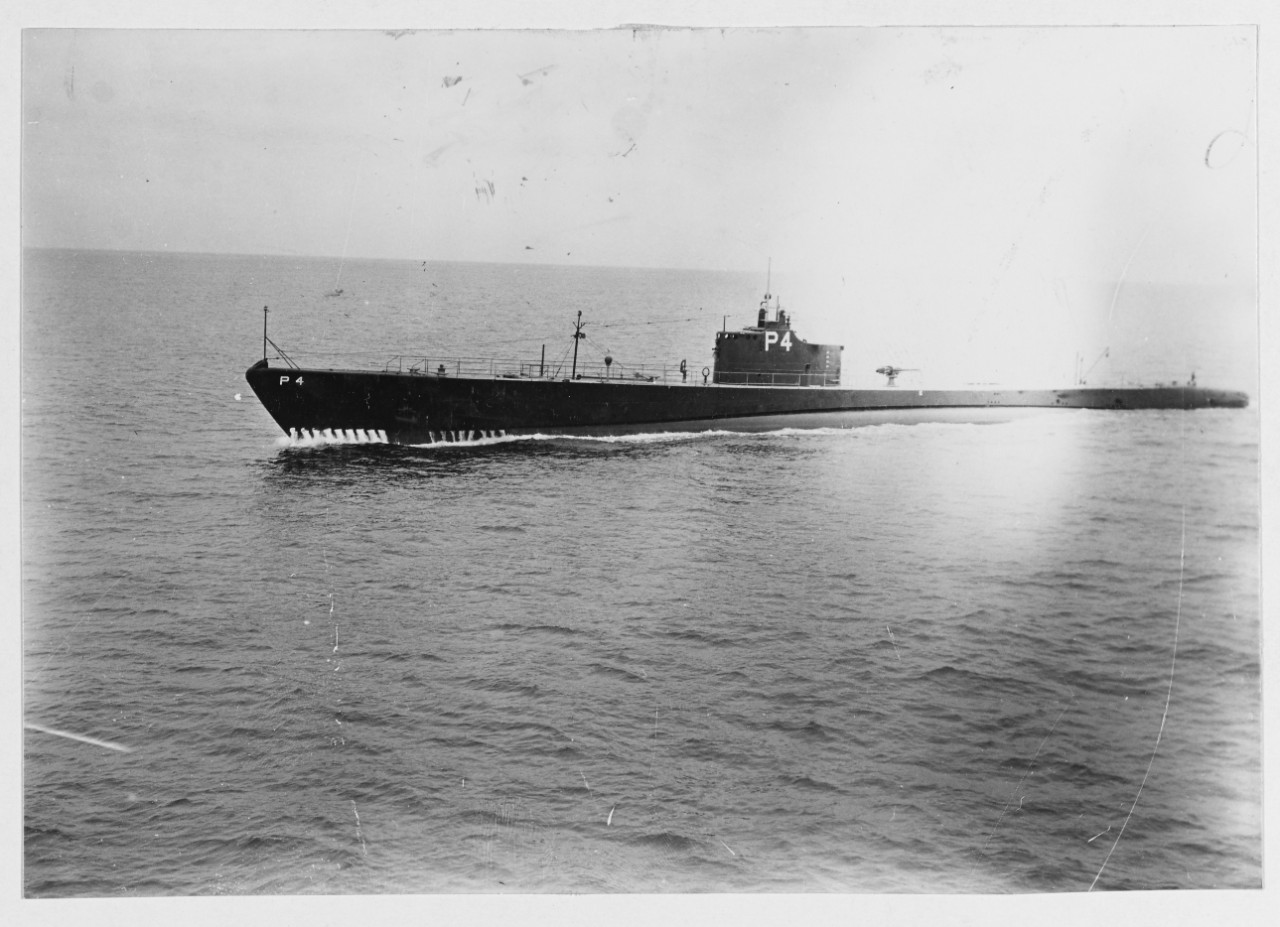

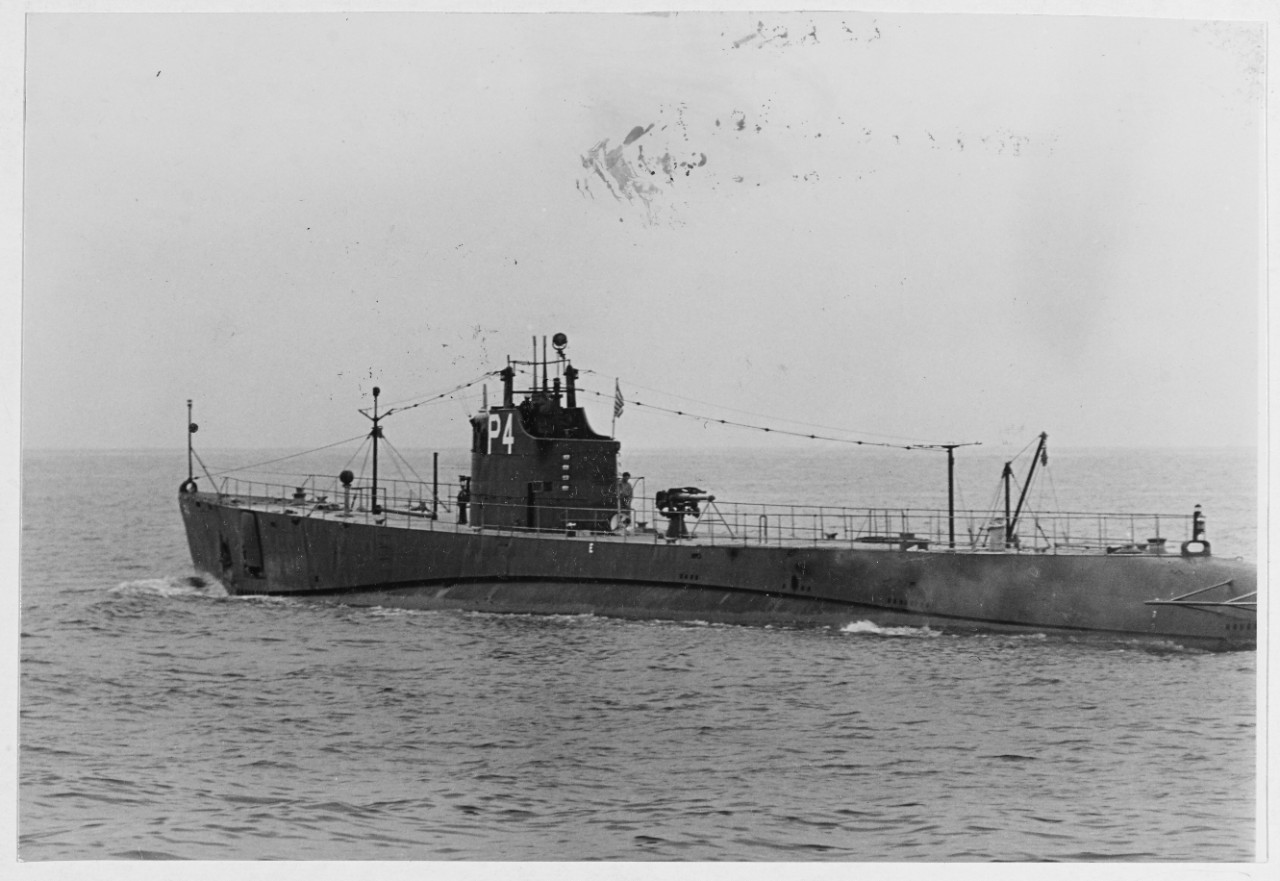

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Catalog #: NH 106576

Above we see the Bogue-class escort carrier USS Block Island (CVE-21), photographed from a blimp of squadron ZP-14 underway on her first ASW hunter-killer cruise, seen off the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 15 October 1943. Arranged on her flight deck are a dozen TBF/TBM Avenger torpedo planes and nine F4F/FM Wildcat fighters of Fleet Composite Squadron 1 (VC-1) — big medicine for such a small flattop. Commissioned just six months prior on 8 March 1943– 80 years ago today– Block Island would have a bright if an unsung career in the Battle of the Atlantic, although she would not live to see it conclude.

About the Bogues

With both Great Britain and the U.S. running desperately short of flattops in the first half of World War II, and large, fast fleet carriers taking a while to crank out, a subspecies of light and “escort” carriers, the first created from the hulls of cruisers, the second from the hulls of merchant freighters, were produced in large numbers to put a few aircraft over every convoy and beach in the Atlantic and Pacific.

Of the more than 122 escort carriers produced in the U.S. for use by her and her Allies, some 45 were of the Bogue class. Based on the Maritime Commission’s Type C3-S-A1 cargo ship hull, these were built in short order at Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation, Ingalls Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, and by the Western Pipe and Steel Company of San Francisco.

Some 496 feet overall with a 439-foot flight deck, these 16,200-ton ships could only steam at a pokey 16 ish knots sustained speed, which negated their use in fleet operations but allowed them to more than keep up with convoys of troop ships and war supplies. Capable of limited self-defense with four twin Bofors and up to 35 20mm Oerlikons for AAA as well as a pair of 5-inch guns for defense against small boats, they could carry as many as 28 operational aircraft in composite air wings. They were equipped with two elevators, Mk 4 arresting gear, and a hydraulic catapult.

Most of the Bogue class (34 of 45) went right over to the Royal Navy via Lend-Lease, where they were known as the Ameer, Attacker, Ruler, or Smiter class in turn, depending on their arrangement. However, the U.S. Navy did keep 11 of the class for themselves (USS Bogue, Card, Copahee, Core, Nassau, Altamaha, Barnes, Breton, Croatan, Prince William, and our very own Block Island), all entering service between September 1942 and June 1943.

Meet Block Island

Oddly enough, our little carrier was not the first named after the sound that lies east of Long Island, N.Y. and south of Rhode Island. The Navy ordered an early Bouge class aircraft escort vessel, AVG-8, under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 161) on 12 May 1941 at Ingalls in Pascagoula, and issued her the name USS Block Island on 3 February 1942. However, the name was canceled the following month as the hull was allocated to the Royal Navy who in turn would launch her as HMS Trailer, then HMS Hunter (D 80), and bring her into service under Admiralty orders in January 1943.

HMS Trailer, ex-USS Block Island (ACV-8), later HMS Hunter (D80), location unknown, 14 January 1943, likely in the Gulf of Mexico. Via ONI Division of Naval Intelligence, Identification and Characteristics Section, June 1943.

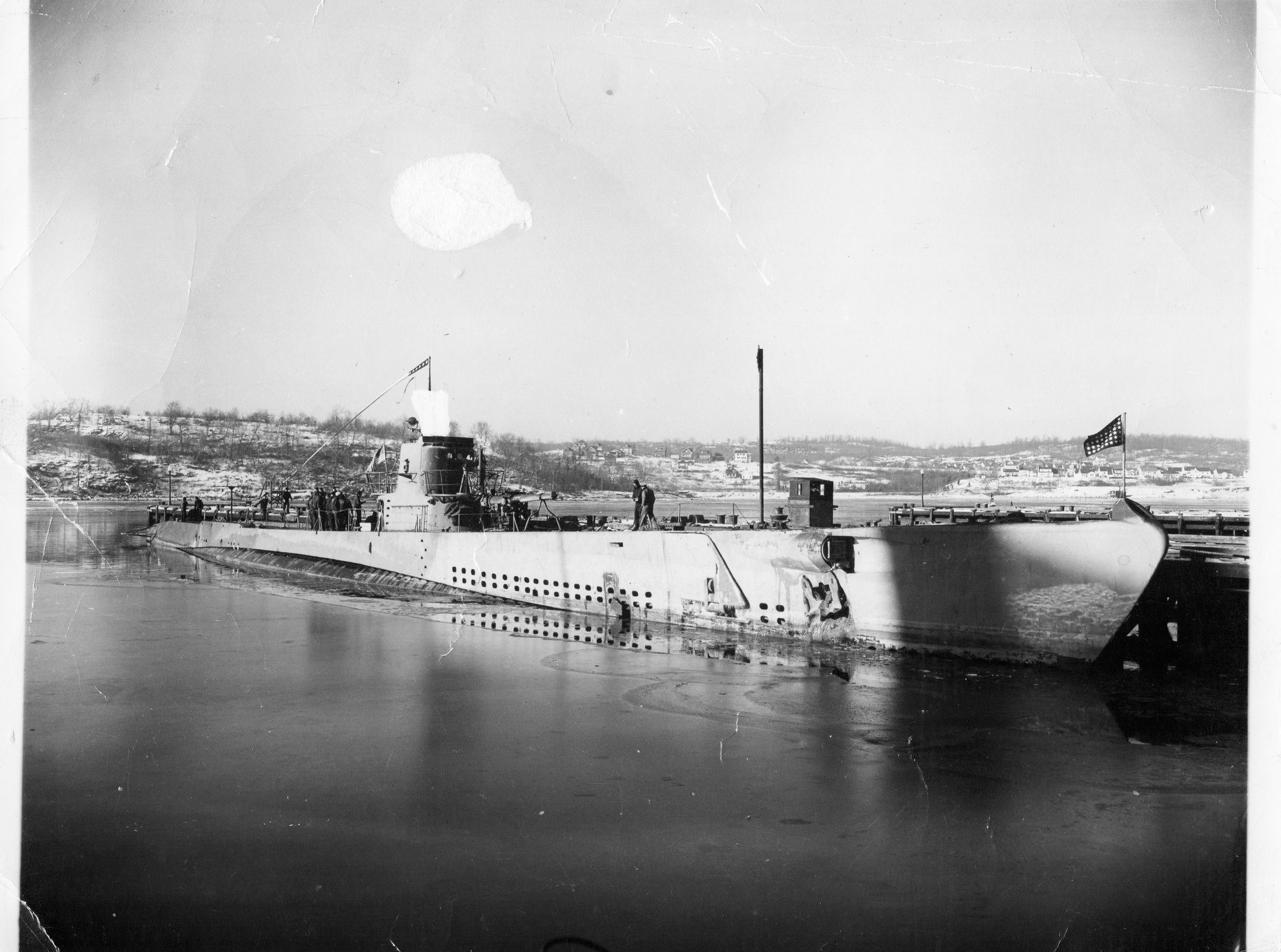

Our subject, the second Block Island, the first to see commissioned U.S. Navy service, was AVG-21, M.C. Hull 237, laid down on the other side of the country at the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation Yard on 19 January 1942. She was named USS Block Island on 19 March 1942– the same day the Pascagoula Block Island had her name canceled, then was reclassified as an auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV-21) and subsequently commissioned on 8 March 1943. As such, she was the eighth of 11 Bogues brought into U.S. service.

Her first skipper, Capt. Logan Carlisle Ramsey (USNA 1919), had made his spot in history already when, on the staff of PATWINGTWO at Ford Island on 7 December 1941, had ordered the famous “Air Raid Pearl Harbor! This is No Drill!” flash message.

Block Island in the final stages of fitting out, at the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation Yard, Seattle, Washington, circa March 1943. 19-N-42715

A series of incredible images exist of her just before commissioning.

Shuttle work

Soon after delivery and an abbreviated shakedown, the new carrier was rushed to the Atlantic where she was urgently needed to tackle the persistent U-boat threat. Picking up the Wildcats and Avengers of Composite Squadron (VC) 25 in San Diego in April, she would arrive in Norfolk via the Panama Canal in early June, where VC-25 would go ashore.

Sailing for Staten Island in July, she took aboard deck and hangar cargo in the form of brand new USAAF P-47D-5 Thunderbolts and rushed them, partially disassembled, to Belfast.

P-47s lashed on the flight deck of USS Block Island (CVE 21). The aircraft is on the forward end of the flight deck, July 13, 1943. 80-G-77750

P-47s lashed on the flight deck of USS Block Island (CVE 21). Viewed from the bridge, looking aft, July 15, 1943. 80-G-77752

USS Block Island (CVE-21). Army P-47-D5 fighters on the ship’s hangar deck, for shipment to Europe, on 15 July 1943. Taken in New York City. 80-G-77754

Arriving back at Staten Island on 11 August, she would load another batch of “Jugs” and set out again for Belfast just 10 days later.

Arrives in Belfast, Ulster, with a load of army P-47 fighters on 7 September 1943. Barge BRAE is in the foreground. 80-G-55524

Port crane unloading army P-47 fighters from USS Block Island (CVE-21) at Belfast, Ulster, on 7 September 1943. The planes were unloaded in a record 14 hours. 80-G-55528

Getting in the Hunt

Upon reaching Norfolk after her second Jug run, Block Island got called up to the majors and, with squadron VC-1 embarked, spent a month in practice runs before shoving out into the Atlantic on 15 October as the centerpiece of Task Group (TG) 21.16, augmented by four destroyers. As an ace in the hole, the group was bird dogged by Ultra Intelligence from decoded German Enigma ciphers.

Although her group caught and damaged the big “milch cow,” U-488, then harassed U-256, and bagged U-222 (Oblt. Bruno Barber) on 28 October 1943, sent to Poseidon by Mk. 47 depth bombs from two of VC-1’s Avengers. U-220, a minelayer boat returning from laying her evil eggs off Newfoundland, went down with all hands.

Exchanging VC-1 for VC-58– the latter’s Avengers now equipped with the new 5-inch HVAR “Holy Moses” rockets– Block Island‘s planes soon chased U-758 in January 1944 on her second hunter-killer cruise but again did not sink her. In the attack 11 January attack, the HVAR was used against a submarine for the first time.

TBF aircraft, (VC-58), from USS Block Island (CVE 21) make the first aircraft rocket attack on a German submarine, U-758, on January 11, 1944. The submarine survived the attack and returned to St. Nazaire, France, on 20 January. In March 1945, it was stricken by the German Navy after being damaged by British bombers at Kiel, Germany. Shown: Lieutenant Junior Grade Willis D. Seeley makes an effective rocket attack followed quickly by a depth-bomb attack by Lieutenant Junior Grade Leonard L. McFord. Lieutenant Junior Grade Seeley then made an effective depth bomb attack. Official 80-G-222842

Her habit of being quick to attack reported U-boats earned her the nickname, “USS FBI” for “Fighting Block Island.”

This would be taken to even greater proportions by her second skipper, Capt. Francis Massie (“Frank”) Hughes (USNA 1923), a tough Alabaman who, like Block Island’s first skipper, had been at Pearl Harbor. During the December 7th attack, Hughes was the first Navy aviator who managed to get his aircraft in the air and did so while still in his pajamas, then later flew during the Battle of Midway.

On 1 March 1944, the Canon-class destroyer escort USS Bronstein (DE 189), part of Block Island’s T.G., reported a depth charge attack that has sometimes been credited as being a kill against U-603 (Kptlt. Hans-Joachim Bertelsmann) which had gone missing about that time.

On 1 March, Block Island‘s trio of destroyer escorts– USS Thomas, USS Bostwick, and Bronstein— depth-charged an unidentified submarine north of the Azores. This is typically thought to be U-709 (Oblt. (R) Rudolf Ites) which was reported missing in the same general area around that time and has never been found.

On 17 March, her aircraft, teaming up with the destroyer USS Corry and Bronstein, sank U-801 (Kptlt. Hans-Joachim Brans) west of Cabo Verde Islands. In that action, a new Fido homing torpedo dropped by an Avenger carried the day. Corry’s bluejackets rescued 47 German survivors.

Air Attacks on German U-boats, WWII. U-801 was sunk on March 17, 1944, by a Fido homing torpedo by two Avenger and one Wildcat aircraft from USS Block Island, along with depth charges and gunfire from USS Corry (DD-463) and USS Bronstein (DE-189). Note, Lieutenant Junior Grade Paul Sorenson strafed, and Lieutenant Junior Grade Charles Woodell depth charged U-801. 80-G-222854

On 19 March, depth charges from an Avenger/Wildcat duo from Block Island sent U-1059 (Oblt. Günter Leupold) to the bottom. Escorts standing by rescued eight survivors.

U-1059 was one of Donitz’s rare torpedo transport boats, a Type VIIF, that went down after one very curious fight that ended up with a waterlogged naval aviator taking enemy POWs into custody at gunpoint.

The sinking of U-1059. At 07.26 hours, the boat was attacked by an Avenger/Wildcat team from USS Block Island operating on ULTRA reports southwest of the Cape Verde Islands. The aircraft completely surprised U-1059, as she was not underway and men were seen swimming in the water. While the Wildcat (Lt (JG) W.H. Cole) made a strafing run, the Avenger dropped three depth charges that straddled the boat perfectly. U-1059 began to sink, but the AA gunners scored hits on the Avenger during its second attack run and it crashed into the sea, killing the pilot and one the crew. The mortally wounded pilot had nevertheless dropped two depth charges that sent the boat to the bottom. Ensign M.E. Fitzgerald survived the aircraft crash and found himself on a dinghy amidst German survivors. He helped a wounded survivor but kept the others at a distance with his pistol until USS Corry arrived and rescued him and eight German survivors, including the badly-wounded commander, Oblt Günther Leupold. (Sources: Franks/Zimmerman)

Shipping out on her third sweep, now VC-55 aboard in April 1944, Block Island’s T.G. damaged the veteran U-boat U-66 and, after a five-day chase, the destroyer escort USS Buckley found and rammed the pesky German submarine. Some 36 survivors captured by Buckley were later transferred to Block Island.

On the night of 29 May 1944, the Type IXC/40 submarine U-549 (Kptlt. Detlev Krankenhagen) managed to penetrate TG 21.11’s anti-submarine screen and get close enough to fire a trio of G7e(TIII) torpedoes at Block Island, hitting her with two.

As detailed by the NHHC:

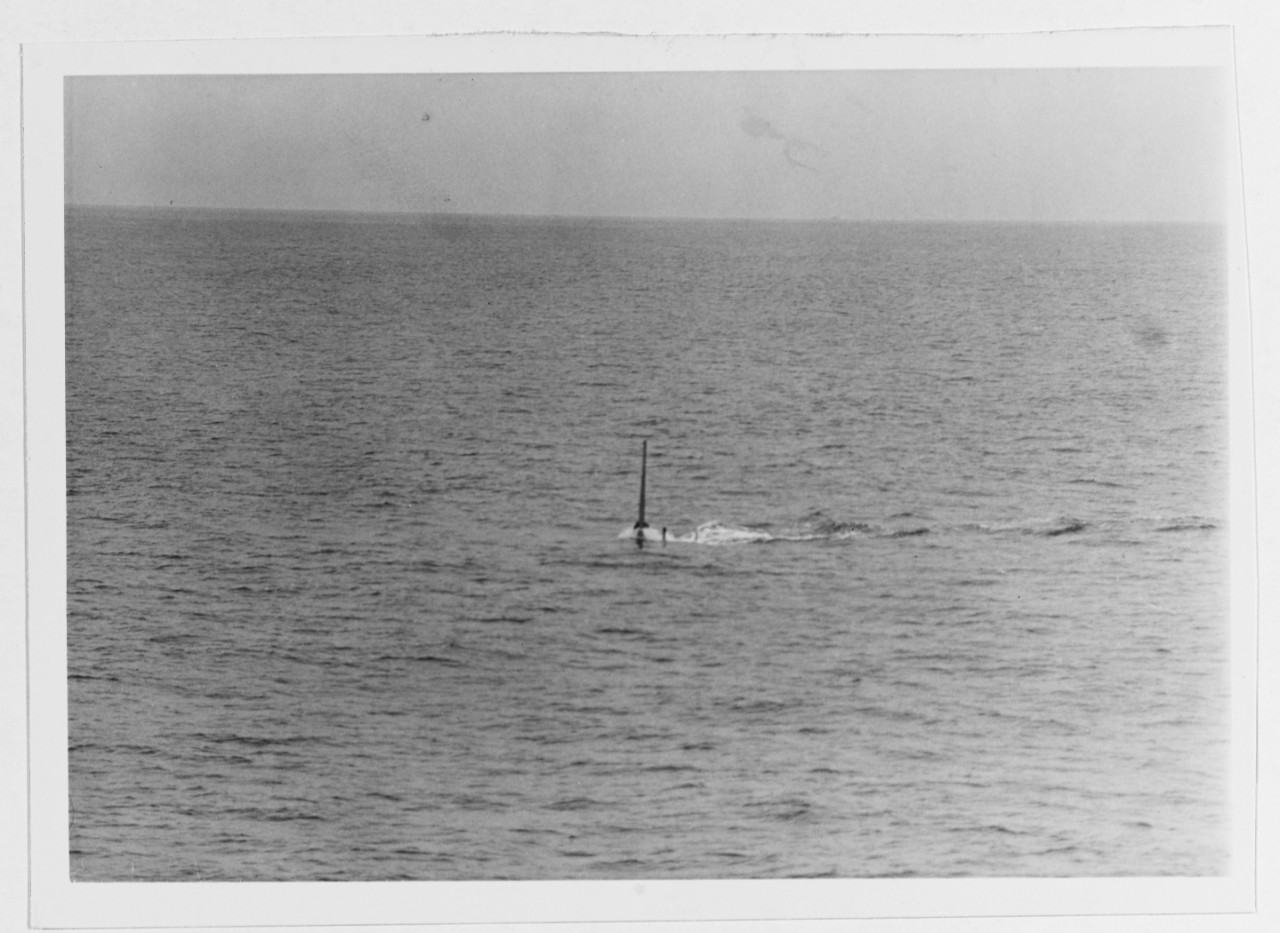

Without warning, U-549’s first torpedo slammed into USS Block Island (CVE-21)’s bow at about frame 12; and, approximately four seconds later, a second struck her aft between frames 171 and 182, exploding in the oil tank, through the shaft alley and up through the 5-inch magazines without causing any further fires or explosions.

Meanwhile, the destroyer escort USS Robert I. Paine (DE-578) closed to join in picking up USS Block Island (CVE-21) survivors as the escort carrier settled lower and lower into the Atlantic. As she sank, the Avengers on USS Block Island (CVE-21)’s flight deck slid off into the sea like toys, their depth charges exploding deep under the surface. USS Block Island (CVE-21) took her final plunge at 2155.

USS Block Island (CVE-21) dead in the water and listing after 1st and 2nd torpedo hits. The ship was initially struck by two torpedoes from the German submarine U-549 on 2013, 29 May 1944. A third torpedo hit some ten minutes later and sealed her fate. FBI sank at 2155. NH 86679.

U-549 was soon after sunk by two of Block Island’s escorts, USS Ahrens (DE-575) and Eugene E. Elmore (DE-686), with all 57 of her crew, Krankenhagen included, diving with her to the bottom forever.

Amazingly, only six USS Block Island crew members died during or soon after the attack. Added to this were four Wildcat pilots aloft at the time of the attack who could not make it to the Canary Islands and were lost at sea.

Block Island’s name was stricken from the Navy List on 28 June 1944.

She was the only American carrier lost in the Atlantic in any war.

She earned two battle stars while her group was credited with sinking seven U-boats. Both of her skippers, Logan Ramsey and Frank Hughes, would survive the war and later retire as rear admirals.

Epilogue

A third Block Island, the second to carry the Navy on active duty, a late-model Commencement Bay-class escort carrier (CVE-106), was commissioned just six months after our ship’s loss, on 30 December 1944.

Of interest, Most of the original CVE 21 crew was reassigned to CVE 106, which was fairly unique in U.S. Navy history. This was done largely due to the will of Frank Hughes, CVE-21’s final skipper, and he would command the new Block Island in 1945.

BuAer photo of USS Block Island (CVE-106), taken on 13 January 1945 off the north end of Vashon Island, Washington. Photo #Stl 1728-1-45.

This new carrier was also able to earn two battle stars for her WWII service in the final days of the Pacific War, then went on to serve again in the Atlantic during the Korean War and was decommissioned in 1954.

A veterans association remembers both CVE-21 and CVE-106.

Our little flattop is also remembered in maritime art.

The war diaries for both Block Islands are digitized in the National Archives.

The most tangible memory of CVE-21 is the Simmons Aviation Foundation’s Heritage Flight TBM-3E Avenger (N85650) that since 2011 carried the “Block Island” livery and tail flash of VC-55.

Of the rest of the Bogue class, Block Island was not the only member to feel the U-boat’s sting. British-operated sister HMS Nabob (D 77) was torpedoed by U-354 in October 1944 and so seriously damaged that she was judged not worth repair. Likewise, the same could be said for sistership HMS Thane (D 48) would be so crippled by U-1172 in 1945 that she was not returned to service.

As for the class’s post-war service, they were too small and slow to be utilized as much more than aircraft transports, and most of the British-operated vessels were returned to the U.S. Navy, retrograded back to merchantmen, and sold off as freighters.

Of the ten U.S.-operated Bogues, most were sold for scrap or for further mercantile use sans flattop and guns, with Card, converted to an aviation transport (AKV-40, later T-AKV-40) in the 1950s, remaining in service into Vietnam where she was embarrassingly holed by Viet Cong sappers in Saigon. The last of the class in American service, she was scrapped in 1971.

The final Bogue hull, the former Smiter-class escort carrier HMS Khedive (D62), continued operating as the tramp freighter SS Daphne as late as 1976 before she met her end in the hands of Spanish breakers.

Specs:

Displacement: 16,620 tons (full)

Length: 495 ft. 7 in

flight deck: 439 ft.

Beam: 69 ft. 6 in

flight deck: 70 ft.

Draught: 26 ft.

Propulsion:

2 x Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company Inc., Milwaukee geared steam turbines, 8,500 shp

2 x boilers (285 psi)

1 x shaft

Speed: 18 knots (designed) 16 actual, max

Complement: 890 including airwing

Armament:

2 x single 5″/51 (later 5″/38) gun mounts

8 x twin 40-mm/56-cal gun mounts

27 x single 20-mm/70-cal Oerlikons

Aircraft carried 18-24 operational, up to 90 for ferry service

Aviation facilities: 2 5.9-ton capacity elevators; 1 hydraulic catapult (H 2); 9-wire/3-barrier Mk 4 mod 5A arresting gear; 262×62 ft. hangar deck; 440×82 ft. flight deck

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!