Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 time period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, April 5, 2023: Jackie’s Toys

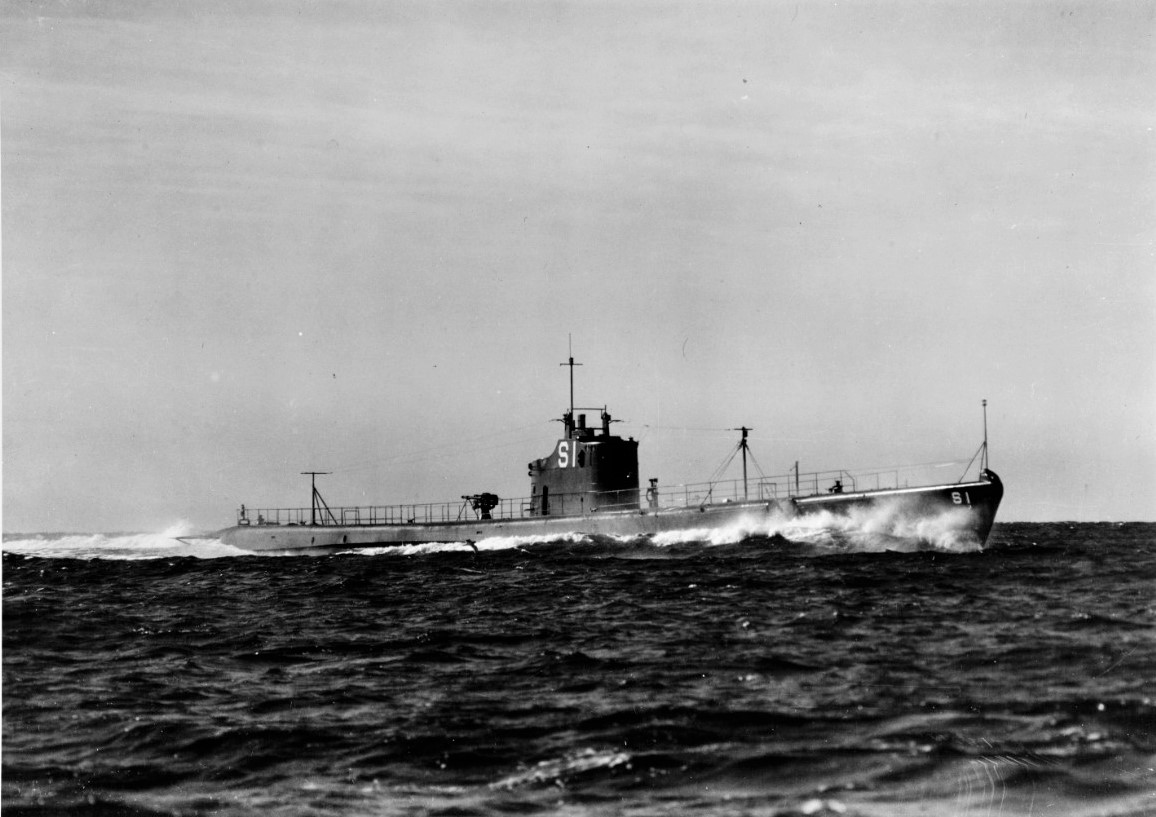

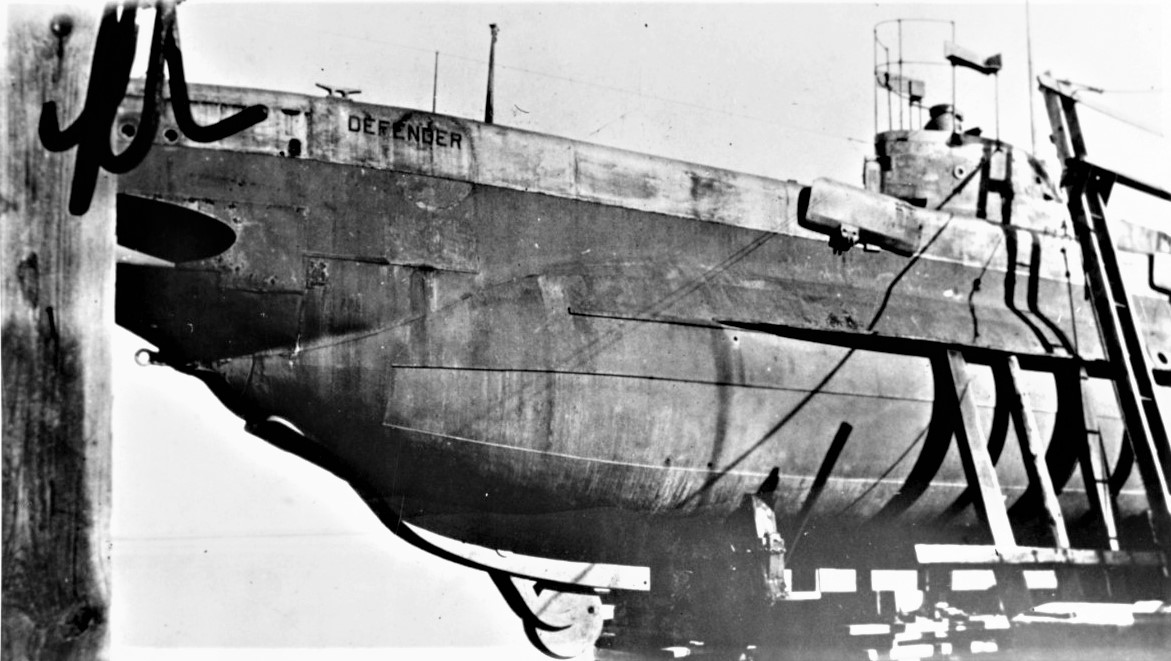

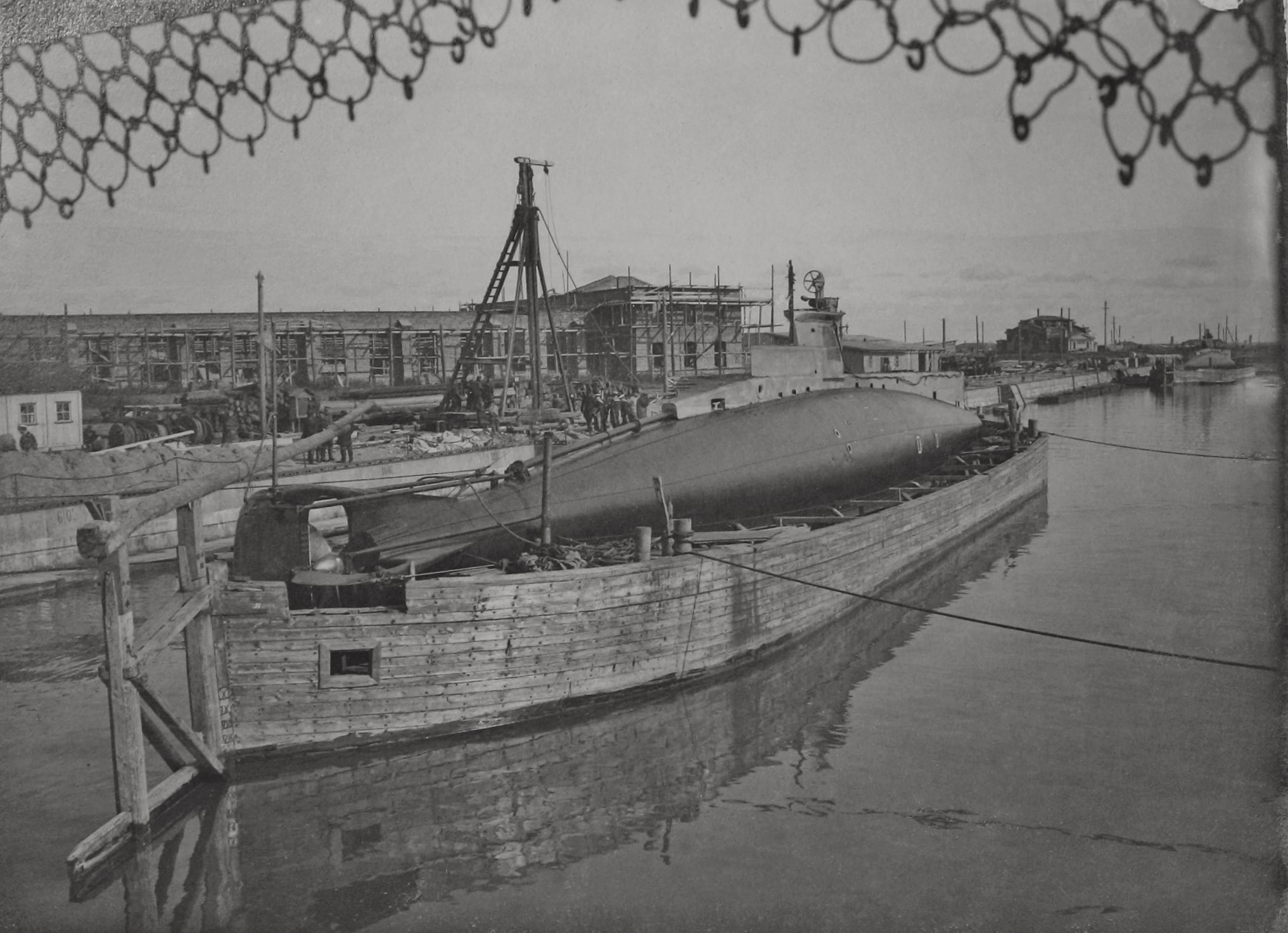

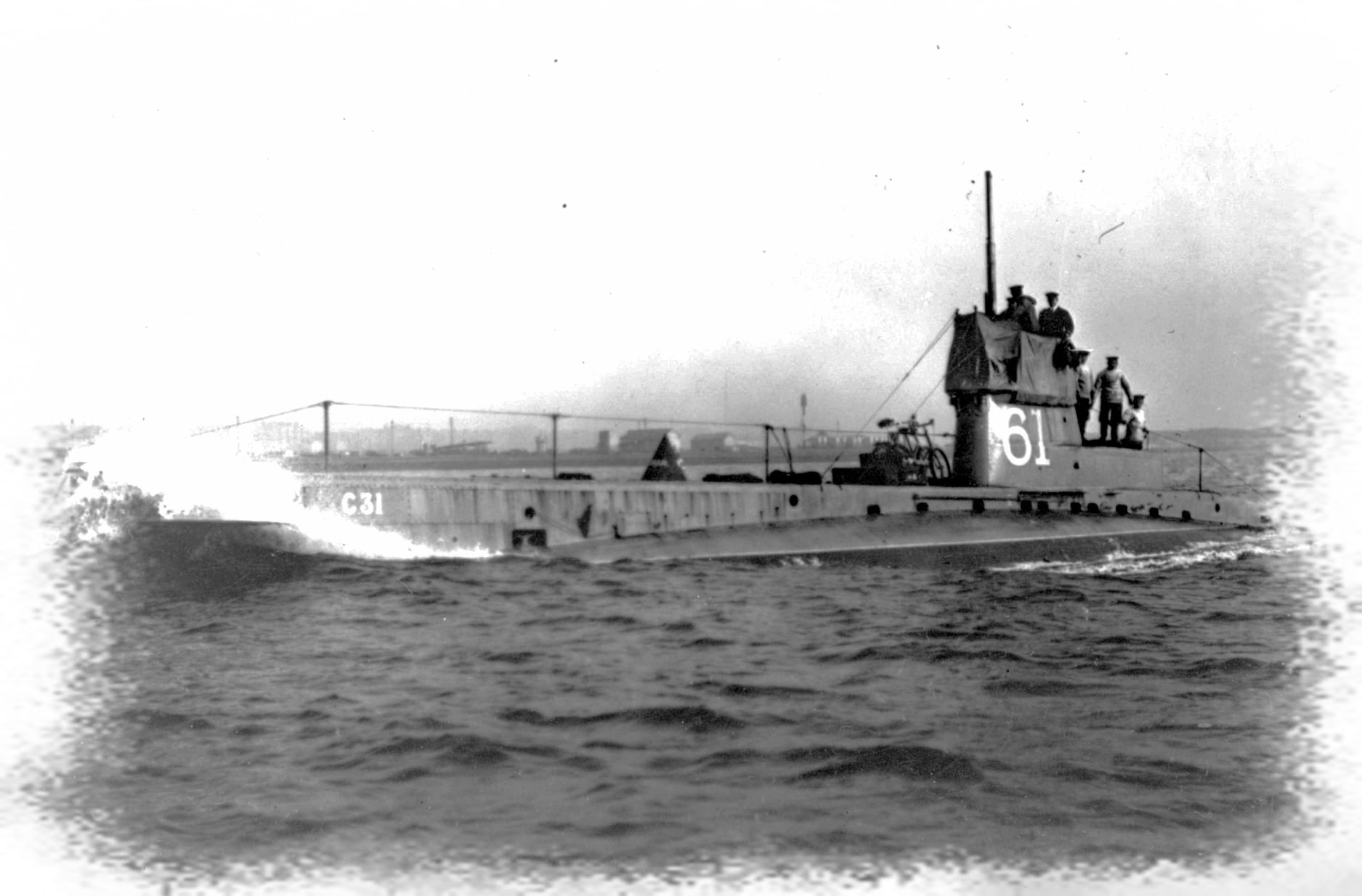

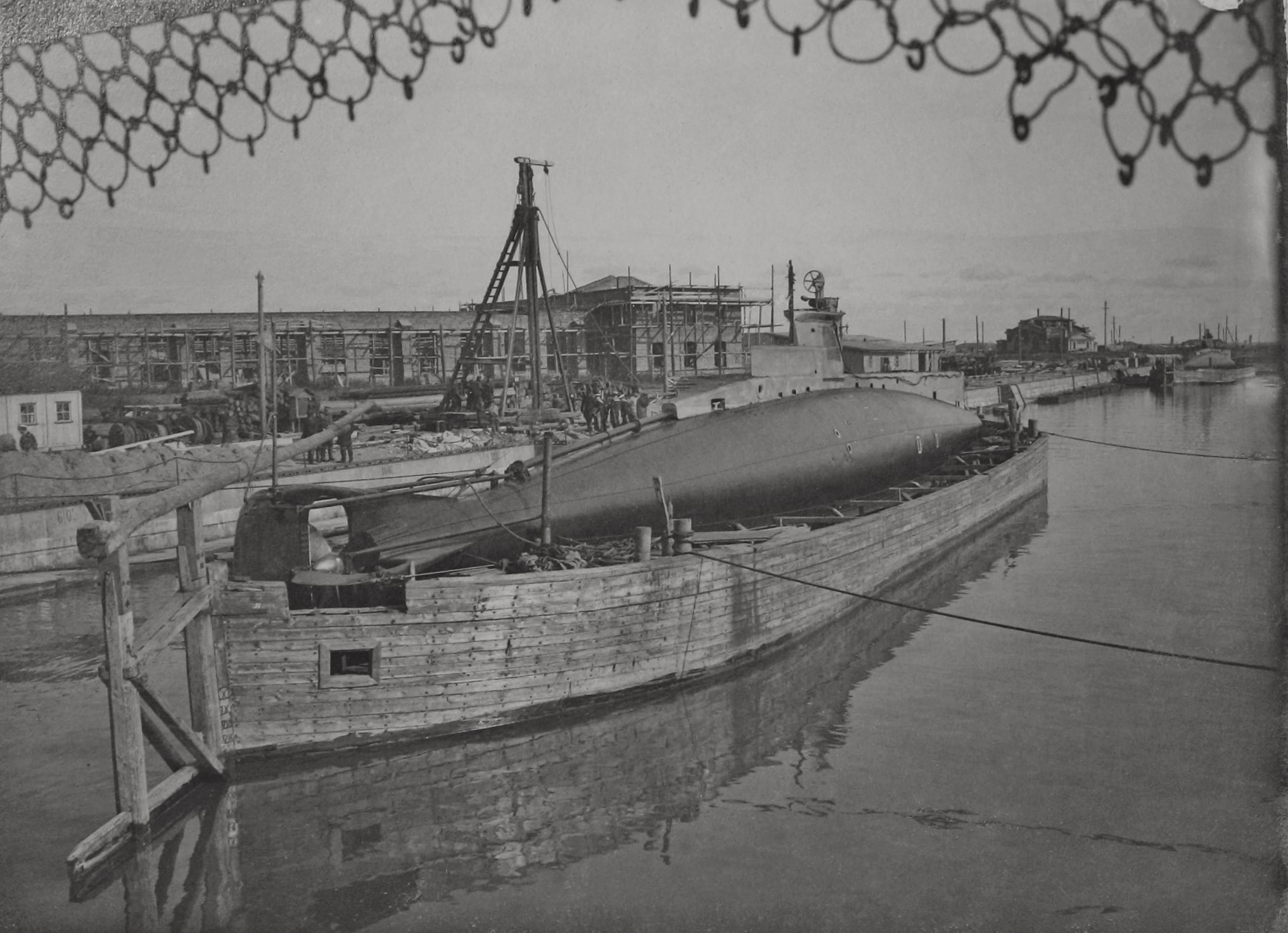

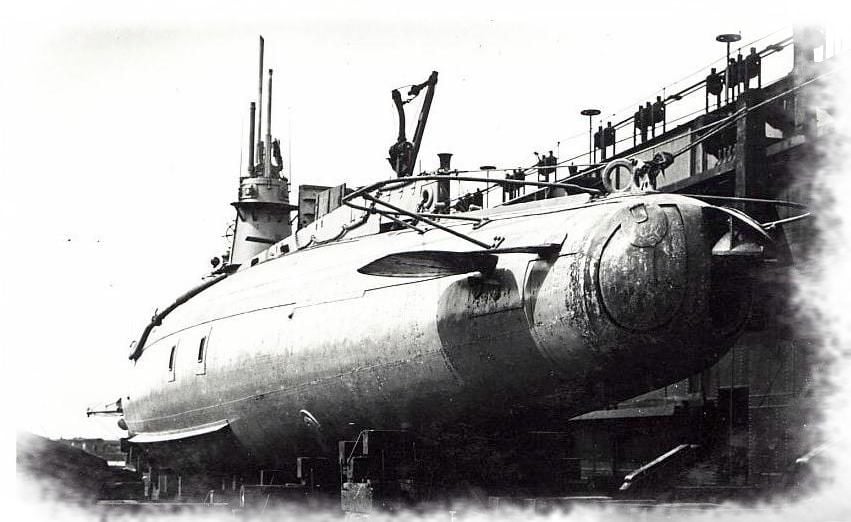

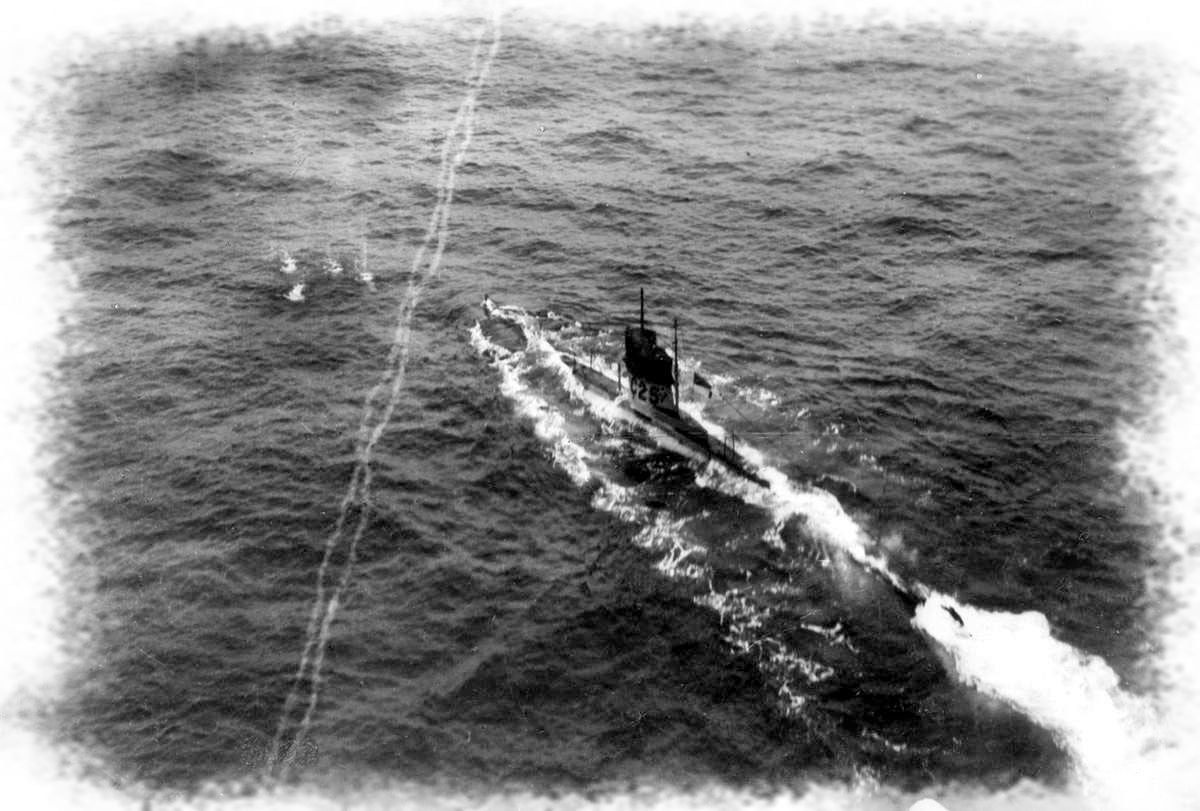

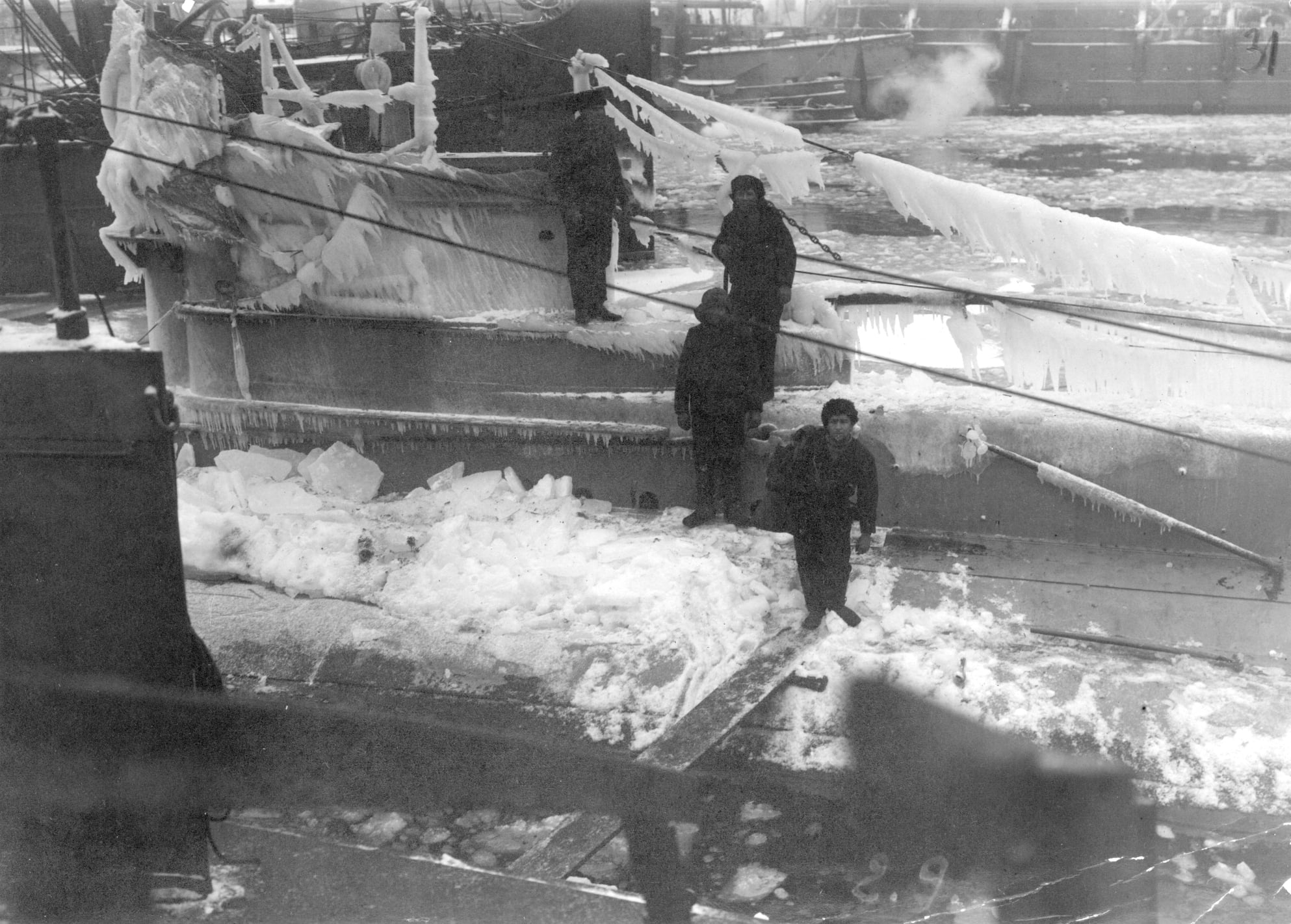

Above we see the British C-class coastal submarine HMS C-27 (57) in the Spring of 1916 as she rides like a beached whale aboard a barge in Russia on her way, via inland lakes and rivers, from Archangel to Petrograd (St. Petersburg), where she would join a flotilla of similar boats in an aim to put the Eastern Baltic off limits to the German High Seas Fleet. You wouldn’t know it by the looks of her, but this little sub had already chalked up one of Kaiser Willy’s U-boats.

Sadly, C27 was lost 105 years ago today, at the hands of her own crew.

The tiny C boats

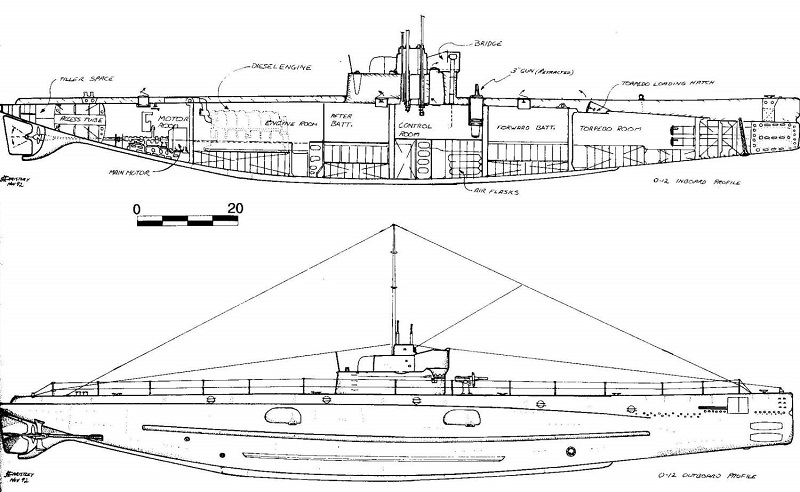

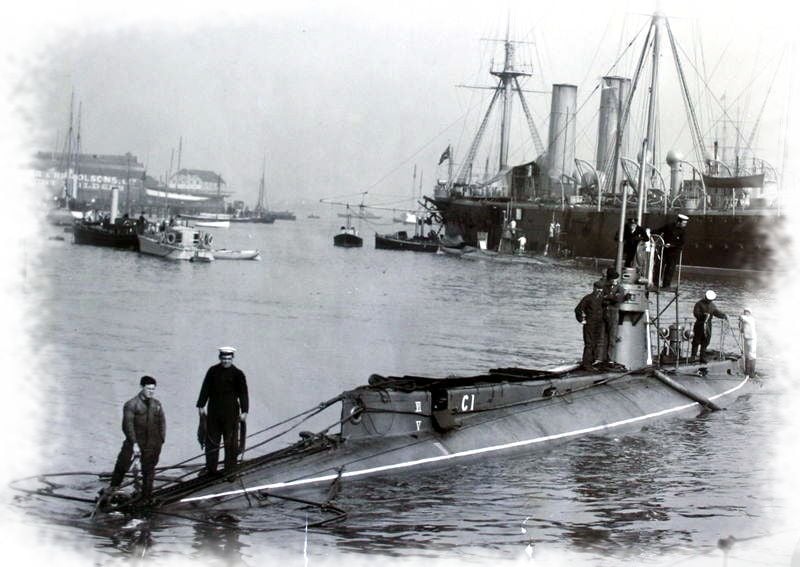

A slightly better and larger follow-up to the 13-strong A-class (200t, 105 ft, 2×18 inch TT, 11.5 kts) and 11-unit B-class (316t, 142 ft, 2×18 inch TT, 12 kts), the C-class boats went some 300 tons and ran 143 feet overall. Powered by a 600hp Vickers gasoline (!) engine on the surface and a single 200hp electric motor when submerged, the C1, as built, could make 13 knots.

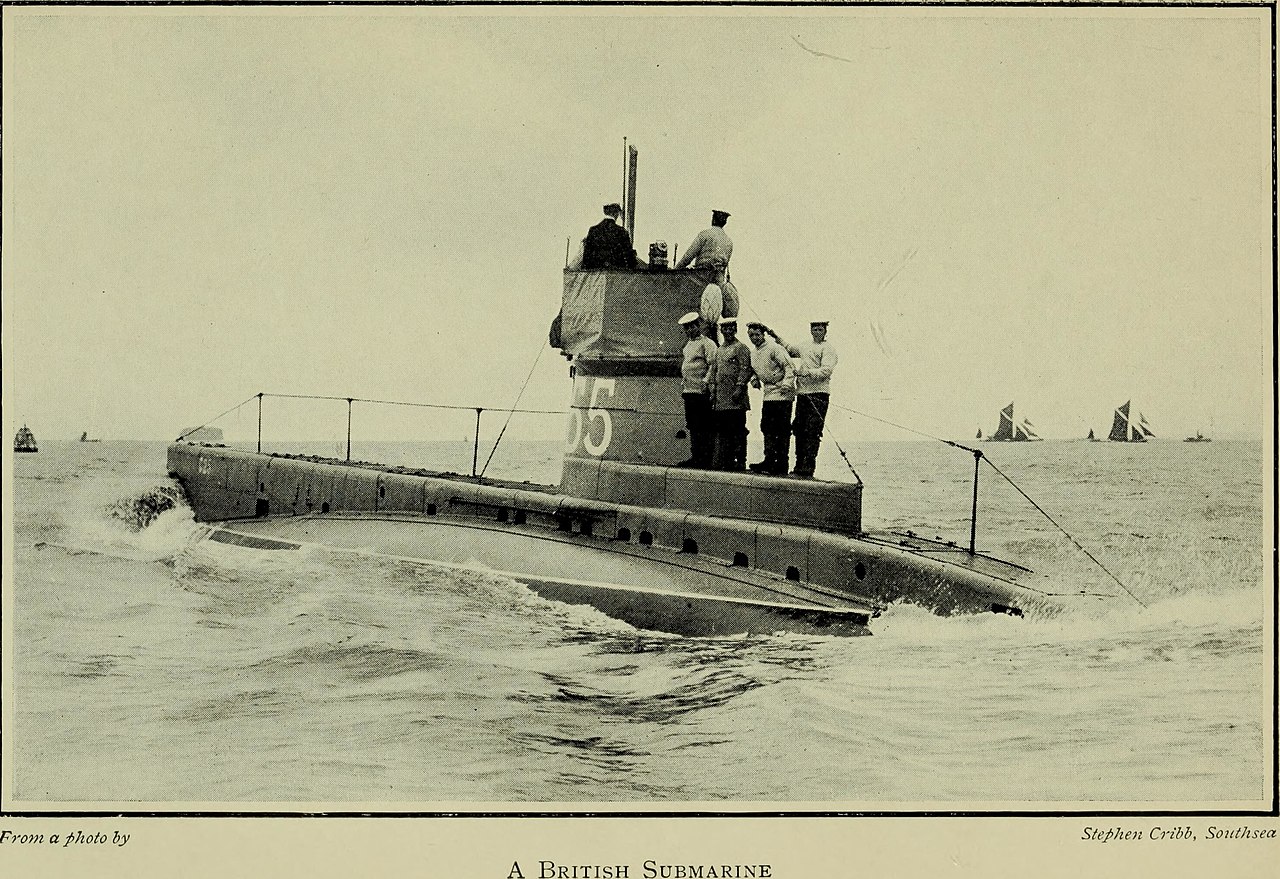

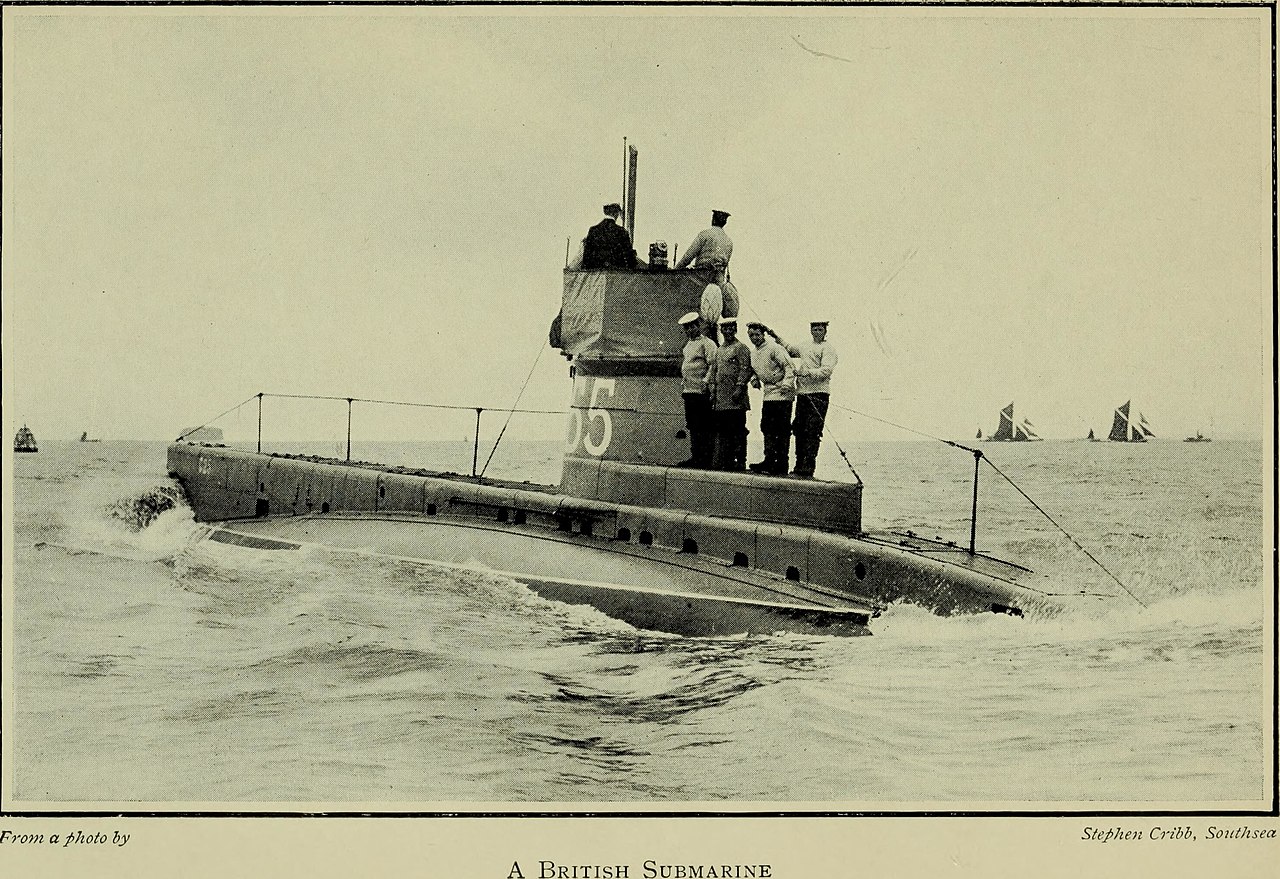

HMS C25. Note the pennant number on the hull is 30 digits off of the name.

Manned by up to 16 officers and crew, they still just carried two 18-inch torpedo tubes with no reloads (although they were designed to carry an extra pair of “fish”) and no deck gun.

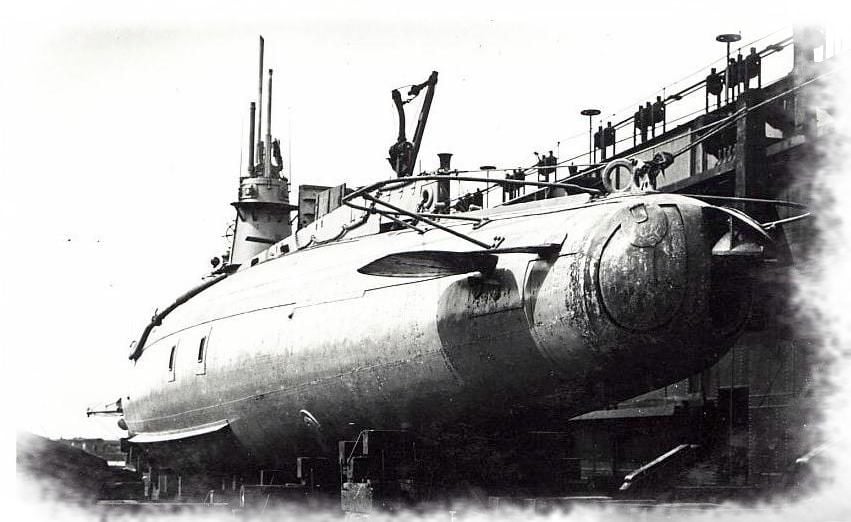

HMS C11. Note her two tubes at the bow under caps

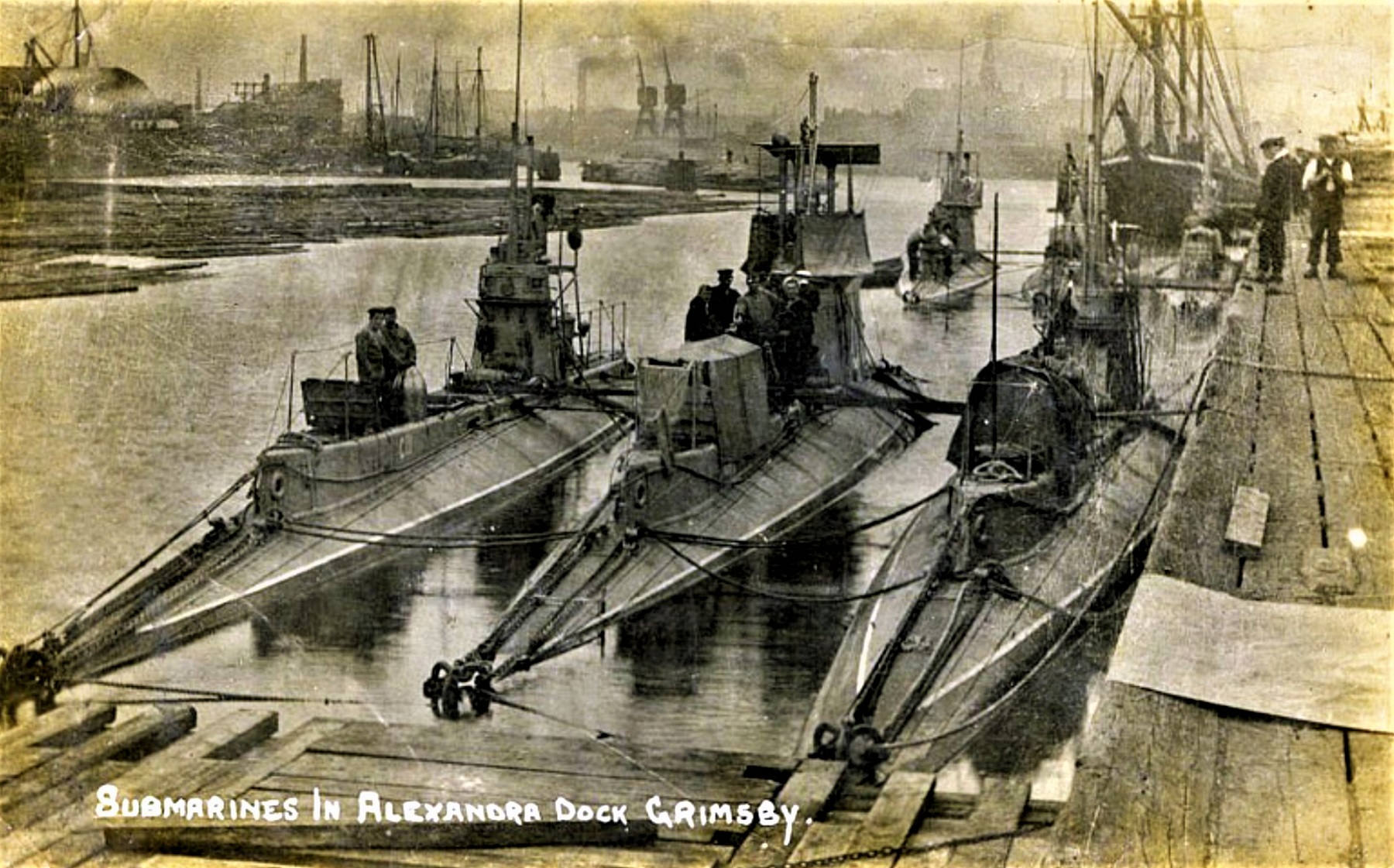

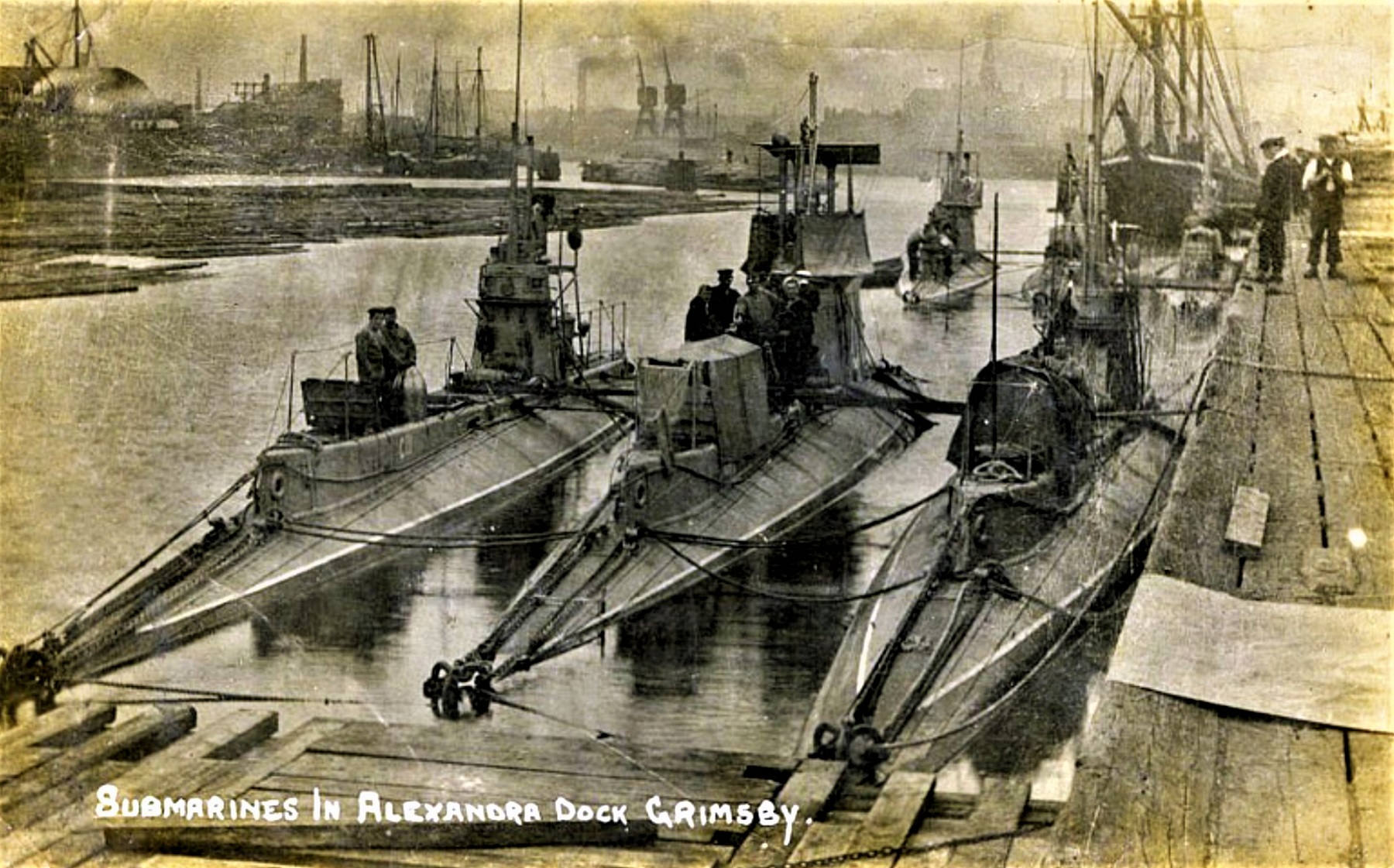

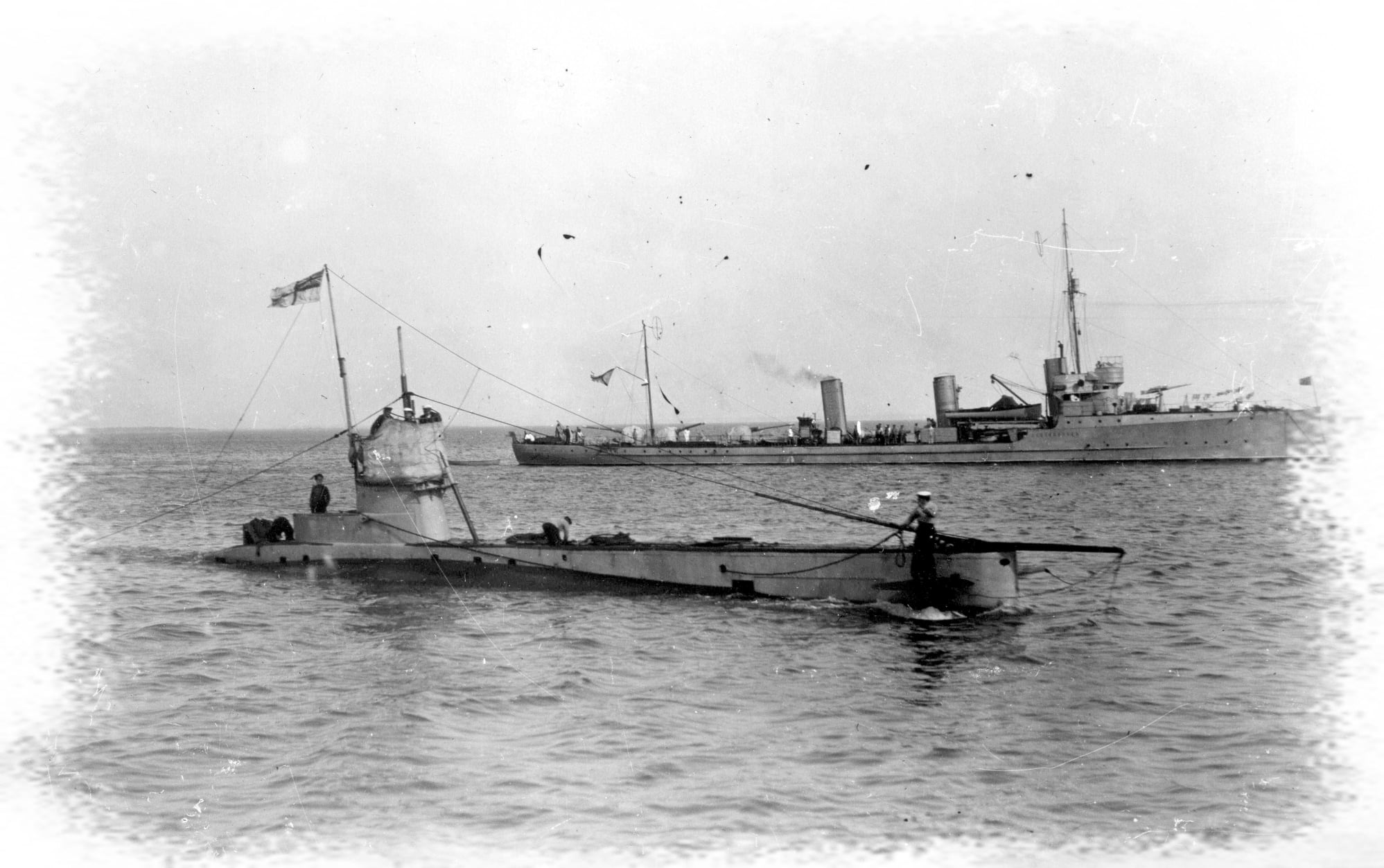

British C class submarines Grimsby

These boats were known at the time in naval circles as “Fisher’s Toys” as Jackie Fisher fancied them instead of minefields for harbor and roadstead defense against enemy sneak attacks.

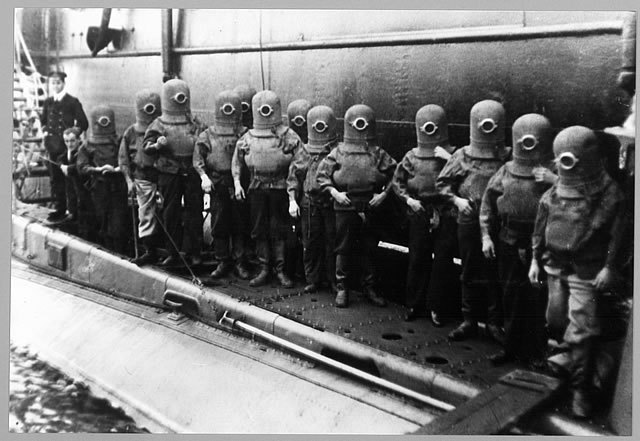

Five of the boats (C12 through C16) were even fitted with three airlocks and enough emergency dive gear for the entire complement should the boat bottom be unable to surface. Certainly, a forward-looking concept. This was later changed to a planned underwater egress via a hatch in the torpedo compartment.

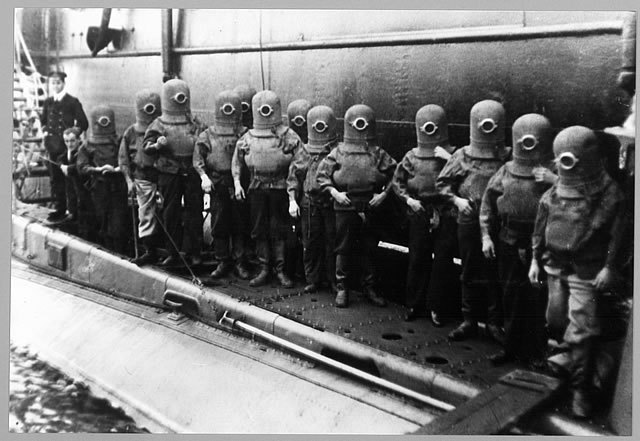

Crew members of the submarine HMS C7 wearing their Rees Hall escape apparatus, dating from the 1900s. “There is no record of the apparatus ever having been used.”

These boats were seriously meant for coastal work, as they could float in just 12 feet of water while on the surface, and they often made appearances in river systems and small littoral harbors.

British submarine HMS C13 moored at Temple Pier, London. July 1909 National Maritime Museum Henley Collection.

A view looking west from Victoria Embankment towards Waterloo Bridge. Three C Class submarines are berthed alongside Temple Stairs, with two torpedo boats moored in Kings Reach at the time of the Thames Naval Review. 23 July 1909. RMG P00045

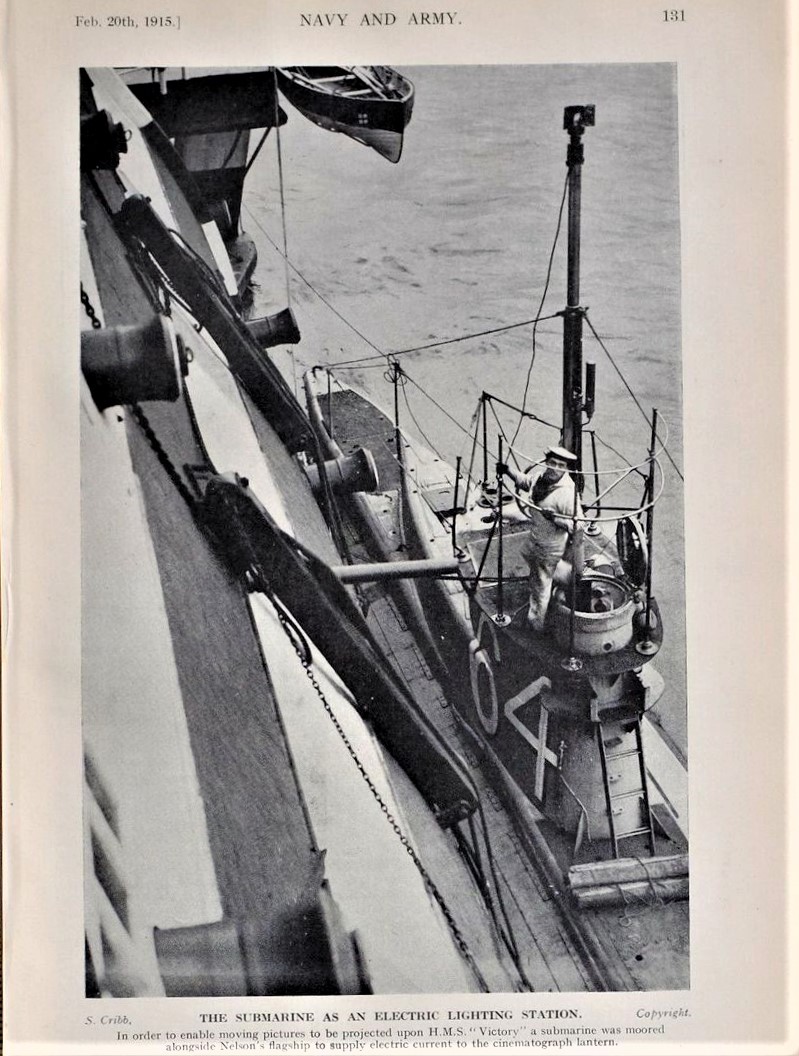

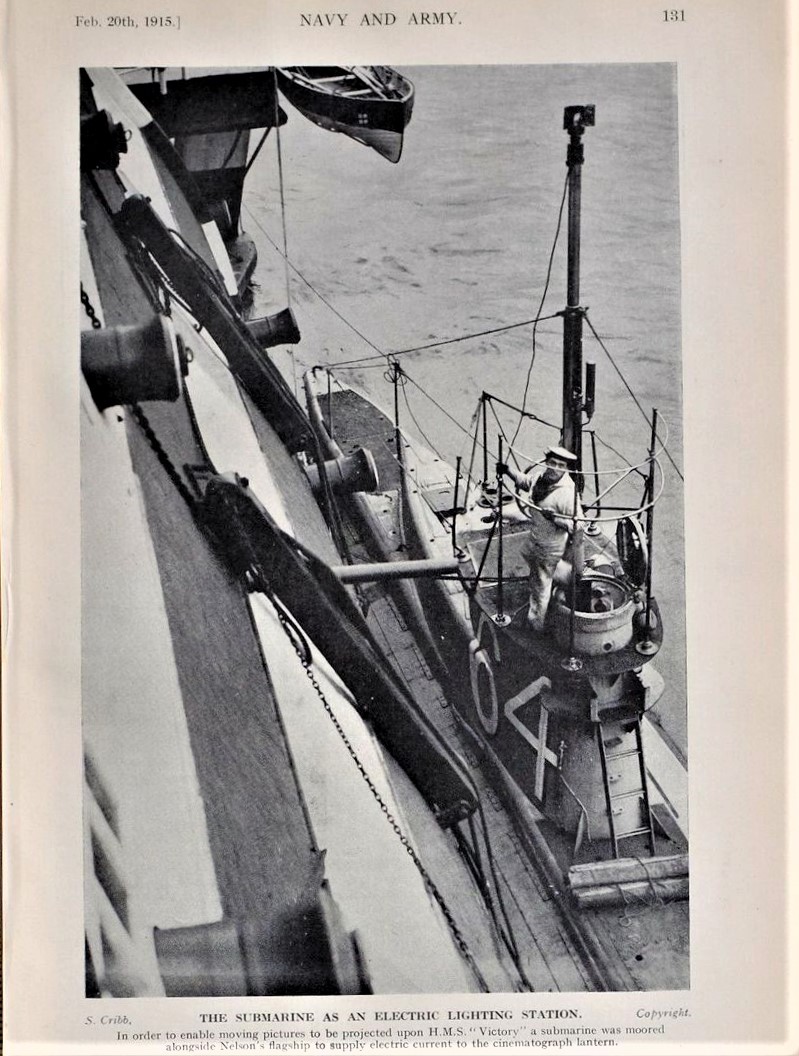

HM Submarine C34 (66) alongside HMS Victory to supply electric current from her generators to power lights and a “cinematograph lantern” for movie night for the cadets’ movie night.

The 38-vessel* class was split into three flights constructed in the half-decade between 1905 and 1910, with the first 18 boats (C1-C18) running a Wolseley 16-cylinder horizontal opposed main engine that allowed a 1,500nm surface radius. The second (C19-30), and third (C31-38) flights were equipped with a more efficient Wolseley-Vickers 12-cylinder engine that gave a better 2,000 nm radius while proving a knot faster (14 surfaced, 10 submerged).

*Two additional units were later built to a modified design for the Chilean government in Seattle and then later taken over by the Canadians (as HMCS CC1 and HMCS CC2) and should be considered their own separate class as they had different engineering and an additional stern torpedo tube along with four bow tubes rather than two.

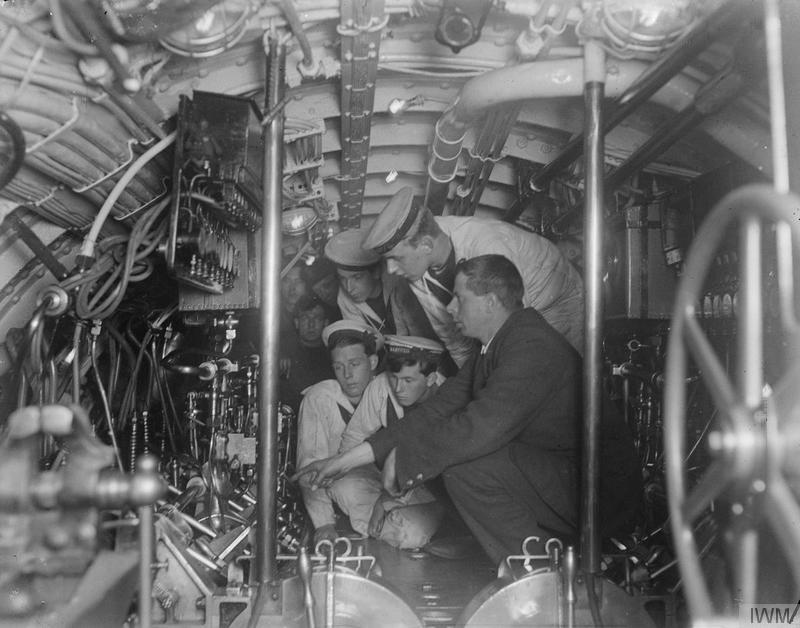

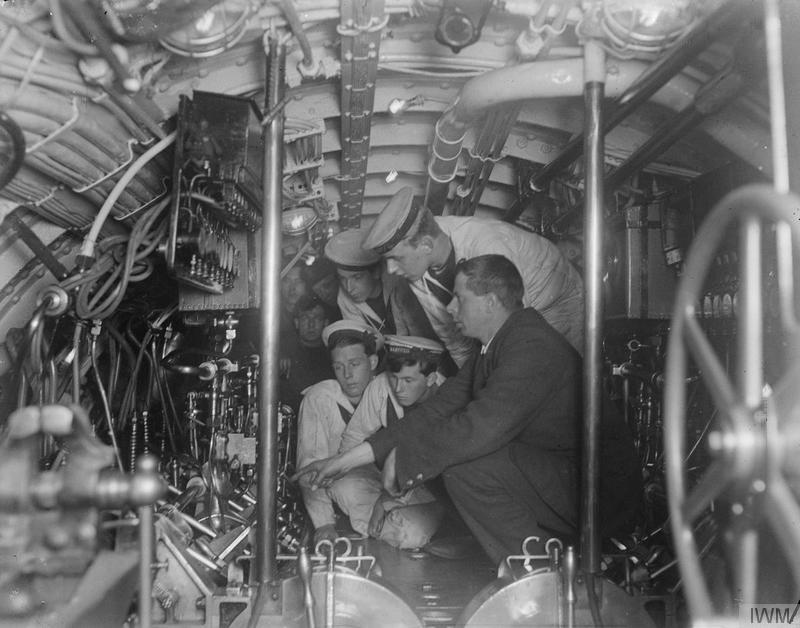

Boy sailors having submarine instruction in the engine room in a C-class submarine in Portsmouth. IWM Q 18868

Most were built by Vickers, as they were a Vickers design, at Barrow, although six were constructed by the Royal Dockyard at Chatham as sort of an educational run.

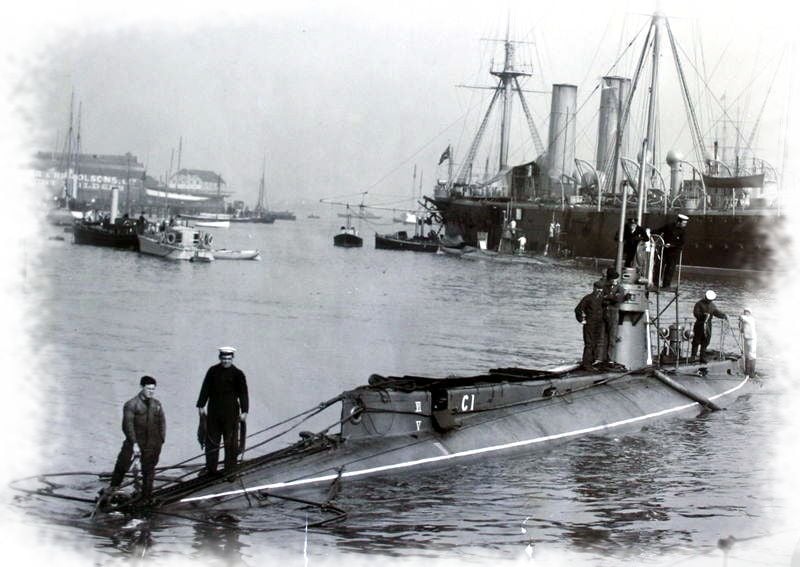

HMS C1

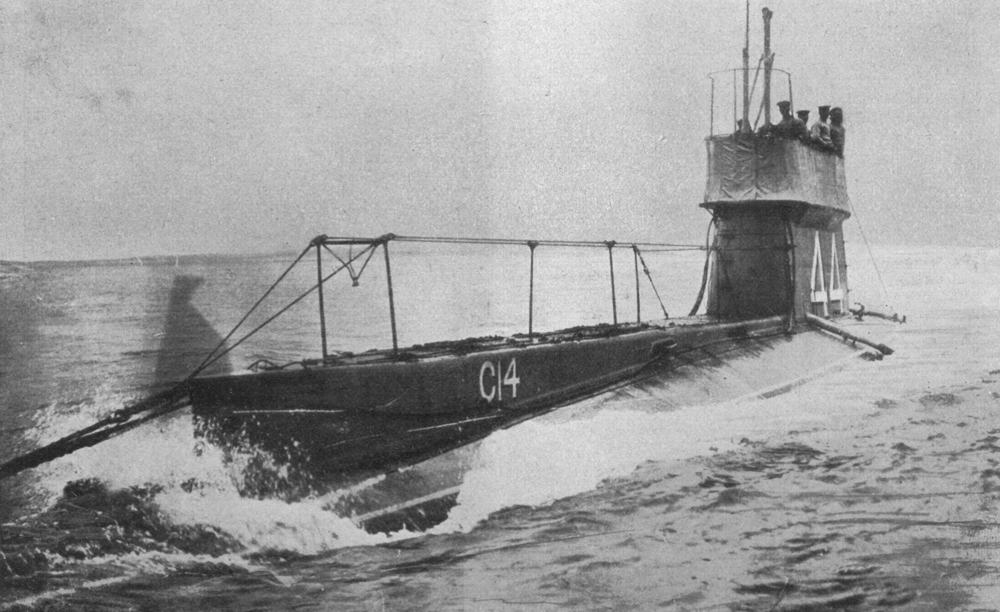

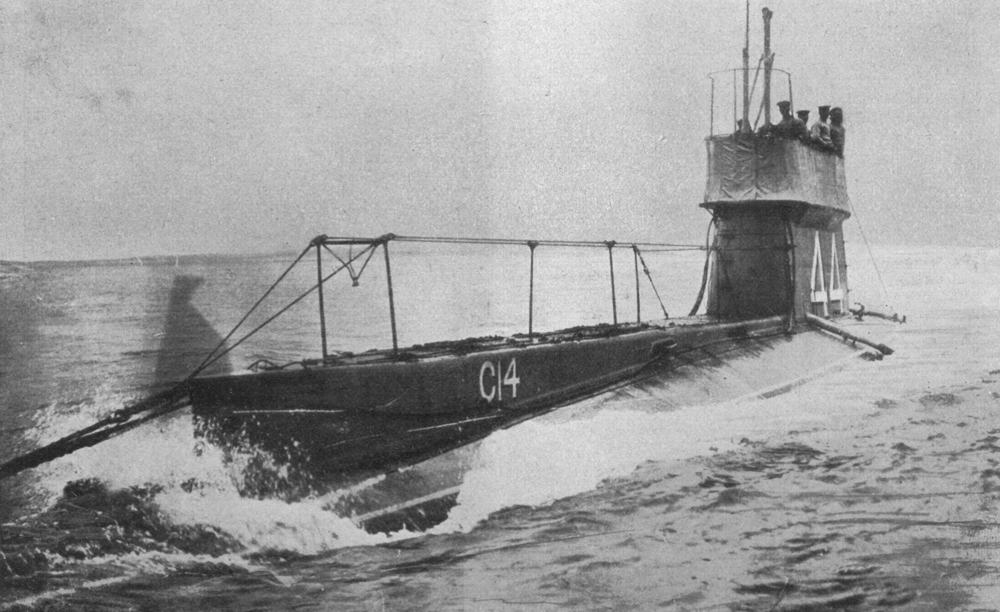

HMS C14 (44)

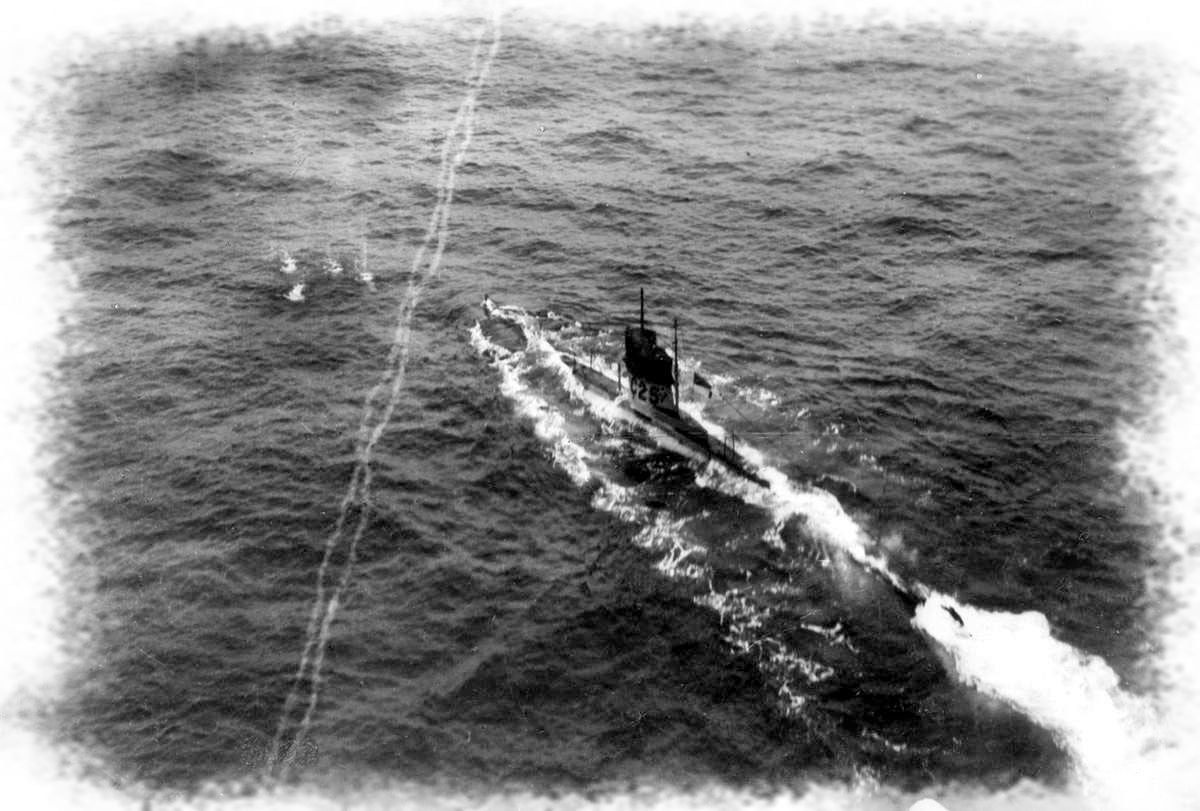

HMS C25

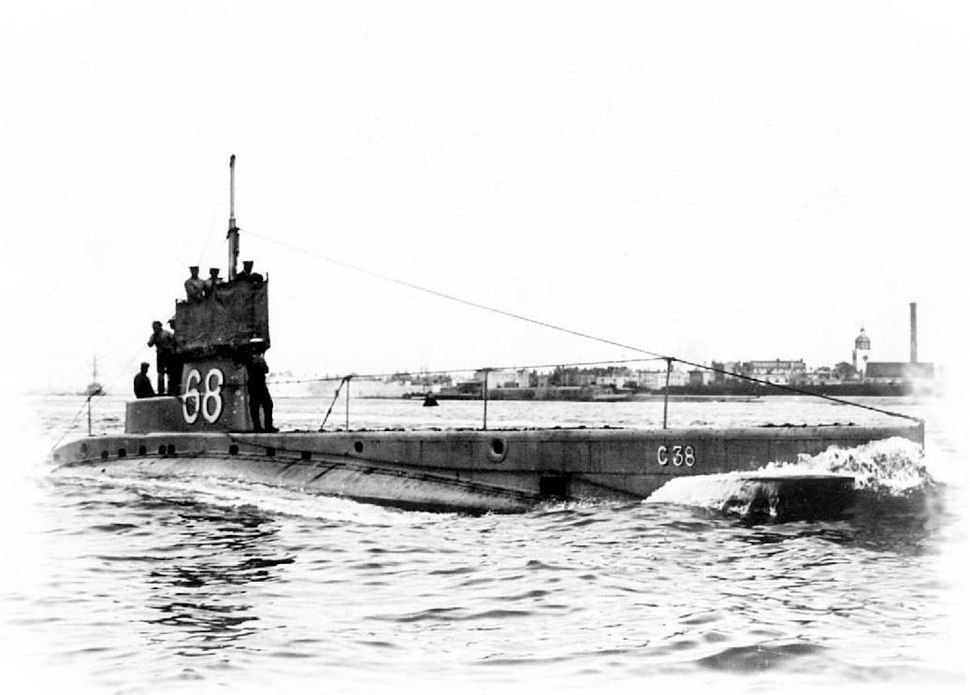

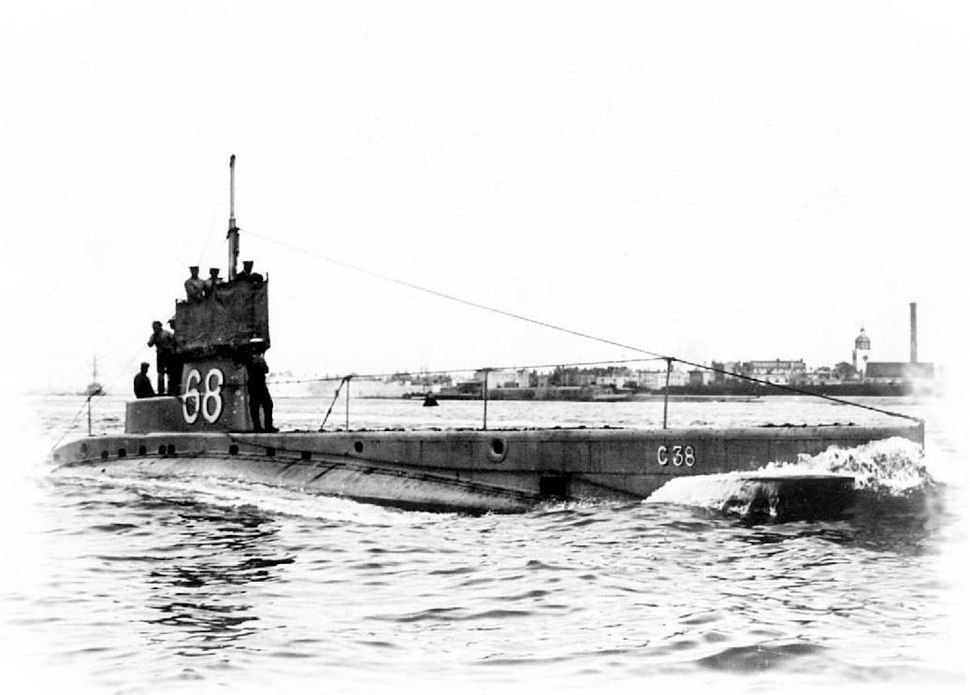

HMS C38 (68)

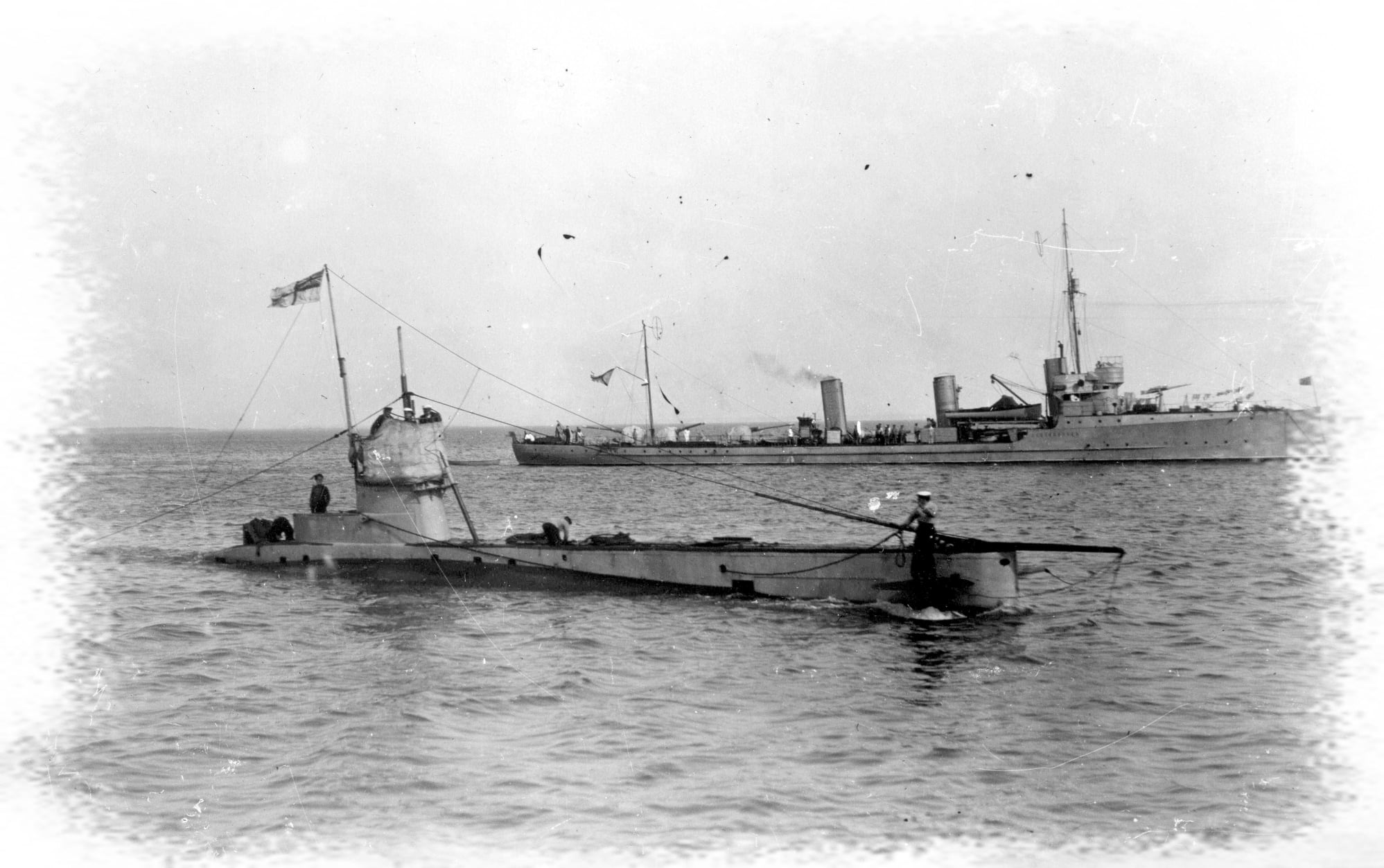

HMS C32

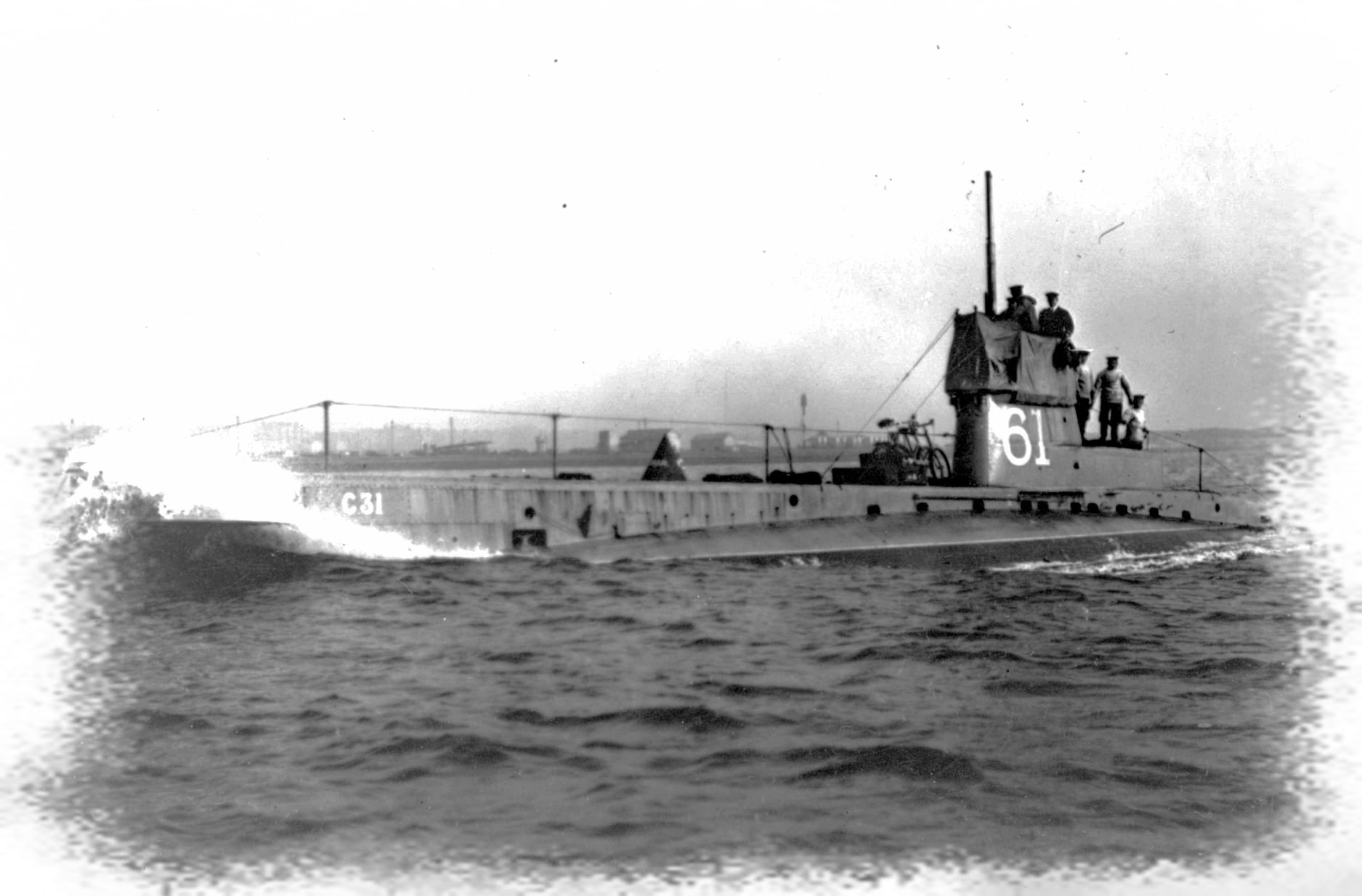

HMS C31 (61)

The class was soon outpaced by the follow-on D and E-classes, which were almost twice as large, could make 16 knots on the surface, and carried safer diesel engines– the C-class submarines were the last class of gasoline-engined submarines in the Royal Navy.

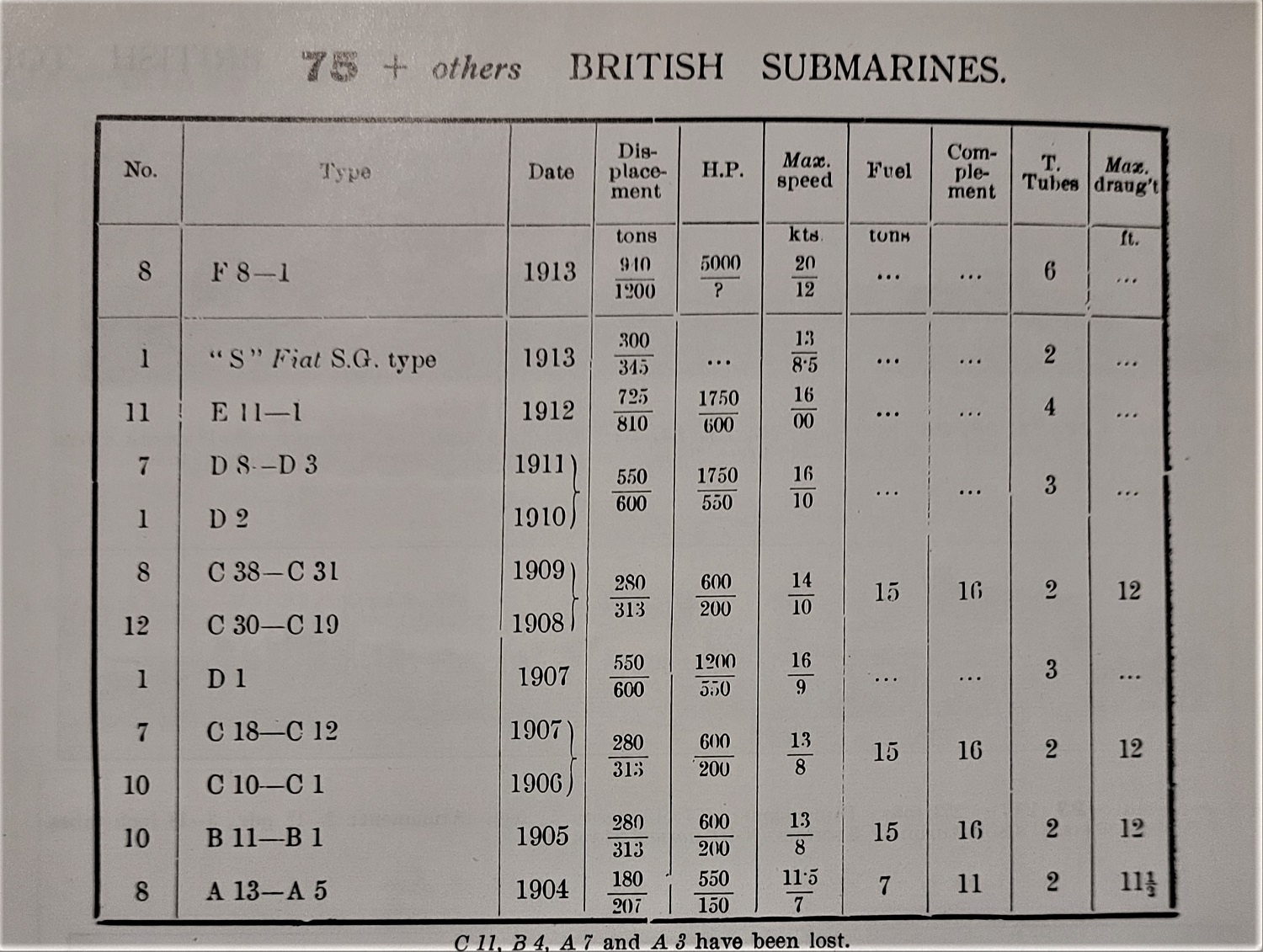

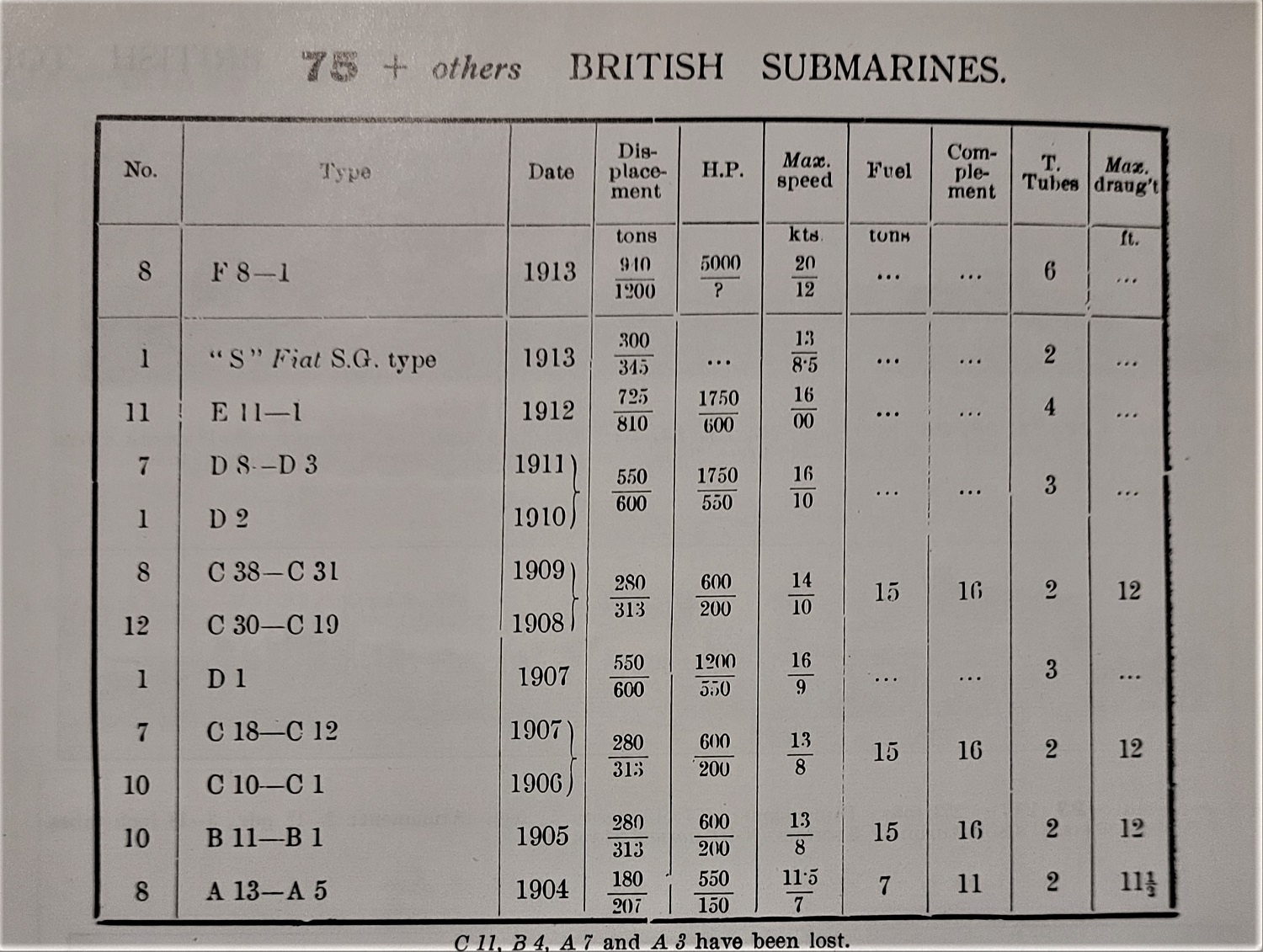

Jane’s 1914 entry for the RN’s 75~ odd submarines, of which the Cs made up fully half of those numbers.

These little boats were tricky as they had very low freeboard while surfaced and the Submarine Force had both tremendous growing and teething pains at the same time. This cost lives as HMS C11 was sunk in a collision with the collier Eddystone in the North Sea in 1909, with only three survivors. In the same incident, HMS C16 and C17 collided but remained afloat. Four years later, HMS C14 was lost in a collision with a coal hopper in Plymouth Sound but was later salvaged and returned to service.

Nonetheless, some of these boats became among the first of HM Submarines to operate in the Pacific as HMS C36, C37, and C38 were transferred to Hong Kong in February 1911 to operate with the China Squadron. Ironically, the Japanese were building a series of almost identical boats at the same time, having bought the plans from Vickers.

By the time the Great War kicked off in August 1914, the remaining C-class boats were generally tasked with coastal defense and training duties in home waters while the larger craft were given more dynamic offensive missions. They did prove deadly in some cases, with HMS C15 for example torpedoing the highly successful German UC-65 (106 ships sunk for 125,000 tons) in the English Channel in November 1917.

U Boat Trap

Suggested in April 1915 by Acting Paymaster F. T. Spickernell, Secretary to VADM Sir David Beatty, as a method to combat German U-boats haunting the British Home Islands, the idea was to team up a trawler in RN service with a small coastal submarine– the Cs were ideal for this– with the fishing boat serving as bait to draw in said Hun to be bashed by waiting C-boat.

As underwater communication was non-existent at the time, and even hydrophones were still a new concept, the trawler, and C-boat were attached by a telephone line. The concept was that the trawler, being too small for the German to waste a torpedo on but still an inviting target, would soon be confronted by surfaced U-boat that would dispatch the fisherman via deck guns or a landing party. Either way, this would set up the idle and unsuspecting German to be zapped by the shadowing C-boat’s submarine volley.

Eight trawlers and a corresponding number of C-boats were tasked to operate from four ports: HMS C26 and C27 were to work with trawlers from Scapa Flow; C14 and C16 from the Tyne; C21 and C29 from the Humber; and C3 and C34 from Harwich.

Put together in May, this “U-Boat Trap” technique soon proved effective, with HMS C24, operating with the trawler Taranaki, sinking U-40 in the North Sea off Eyemouth on 23 June 1915.

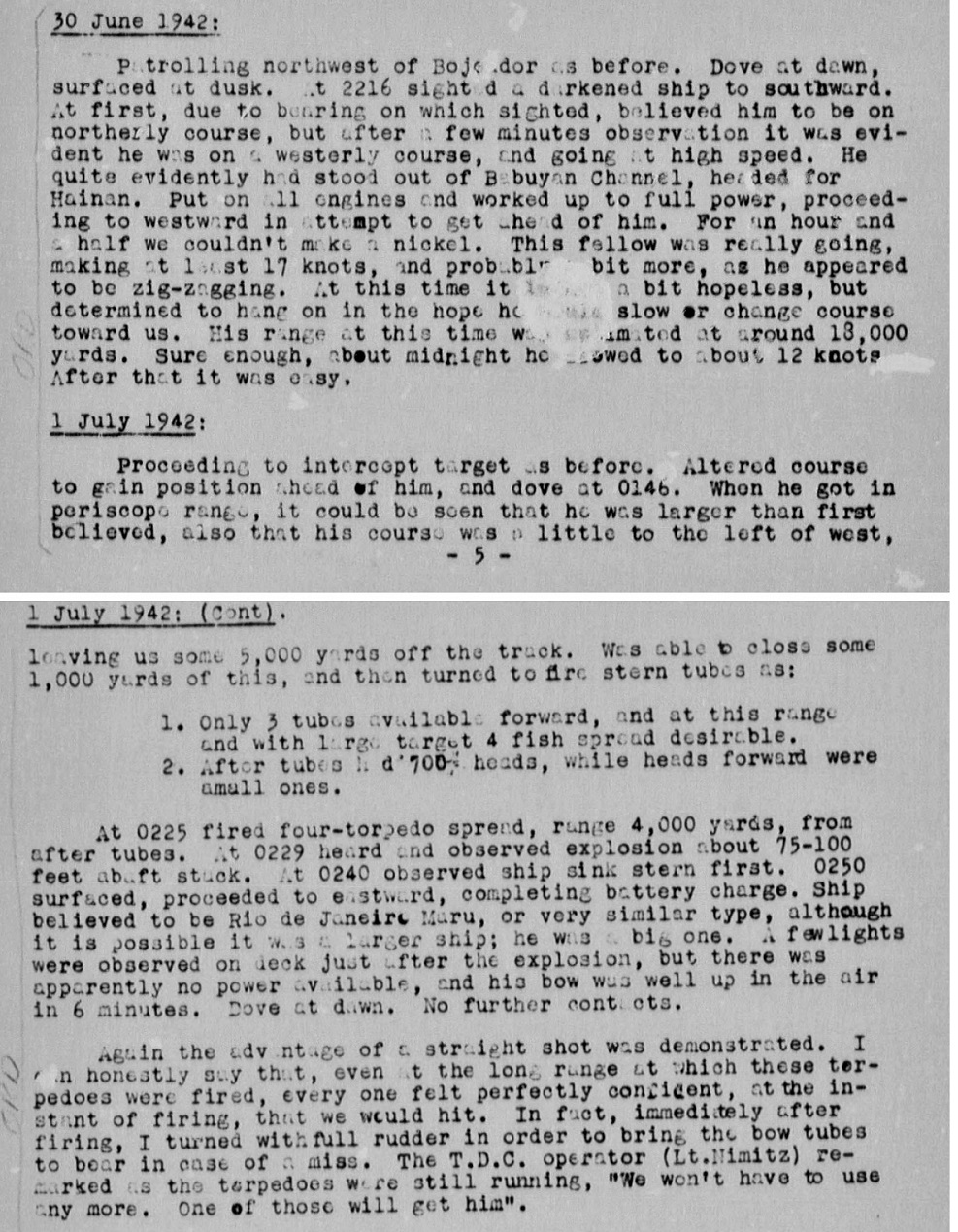

This was followed up by our HMS C27, under the command of LCDR Claude Congreve Dobson, along with the trawler Princess Louise, ending the career of U-23 in the Fair Isle Channel between Orkney and Shetland on 20 July. She made good on this after missing a shot at U-19 the month prior.

As detailed in Martin Gibson’s War and Security Blog on the Royal Navy in the Great War:

The trawler was captained by Lieutenant L. Morton, but Lieutenant C. Cantlie and Lieutenant A. M. Tarver were also on board in order to train the crew. Cantile, who was the only regular officer of the three, the others being peacetime merchant marine officers who were members of the Royal Navy Reserve, took command during the subsequent operation.

At 7:55 am on 20 July Cantlie telephoned Dobson to tell him that a U-boat had been spotted 2,000 yards away. The phone then broke down; Dobson waited five minutes before slipping the cable; contact had not been restored, and he could hear gunfire.

The U-boat, which was U40, had fired one warning shot before firing at the trawler. She stopped, raised the Red Ensign, and dipped it as a sign of surrender, whilst her crew prepared to abandon ship in an apparent panic. This was in accordance with the plan, which was to trick the Germans and hopefully persuade them to come closer. It worked so well that U40 stopped near the trawler.

The trawler’s crew did not know where C27 was, but she was only 500 yards away on U40’s starboard beam when Dobson raised her periscope. He fired a torpedo, but U40 then started her engines, and it passed under her stern. He fired another that hit and sank U40. The British rescued 10 survivors, including her captain, Oberleutnant Hans Schulthess, and two other officers.

The British Naval Staff Monograph, written after the war for internal Royal Navy use only, stated that the prisoners ‘gave a good deal of information, not only of a technical character…but also on the general work of German submarines’, which it suggests may have been a result of their good treatment.

However, the U-Boat Trap results were mixed, with HMS C33 mined off Great Yarmouth while operating with the armed trawler Malta on 4 August. This was repeated when HMS C29 was lost when her companion trawler, Ariadne, strayed into a minefield in the Humber on 29 August. These losses, coupled with the increasing German wariness to fall for the bait of trawler decoys and larger Q-ships, led to the end of the program.

Nonetheless, the RN had other plans for C-27.

Headed East

With Tsarist Russia’s main ports in the Black Sea closed down by the entrance of the Ottomans to the war, and the Germans controlling the Baltic, the Imperial Russian Navy was effectively bottled up except the obsolete and neglected Siberian Flotilla. As an attempt to aid the Russians via their extra naval capacity, Britain and France attempted to force the Dardanelles and break into the Black Sea in a fiasco that was soon followed up by the slow-moving Salonika campaign.

At roughly the same time as the Gallipoli misadventure, the Royal Navy was sending a few small E-class boats through the Baltic to give the Russians some extra torpedo tubes to throw at German shipping.

Three British E-class boats in mid-October 1914 attempted the dicey journey into the Baltic through the Oresund Strait separating Denmark from Sweden, against tough German opposition. This saw HMS E-11 forced to turn back while HMS E-1 and E-9 got through to Reval in the Gulf of Finland.

Iced in over the winter, the following summer they soon torpedoed and sank a German collier, and badly damaged the destroyer SMS S-148, the battlecruiser SMS Moltke, and the cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert. Such exploits brought a meeting with the Tsar, and boxes of Russian decorations including the St. George, the country’s highest.

In late 1915, E-1 and E-9 were joined by E-8, E-18, and E-19, while sister E-13 was disabled after she ran aground in Danish waters and interned.

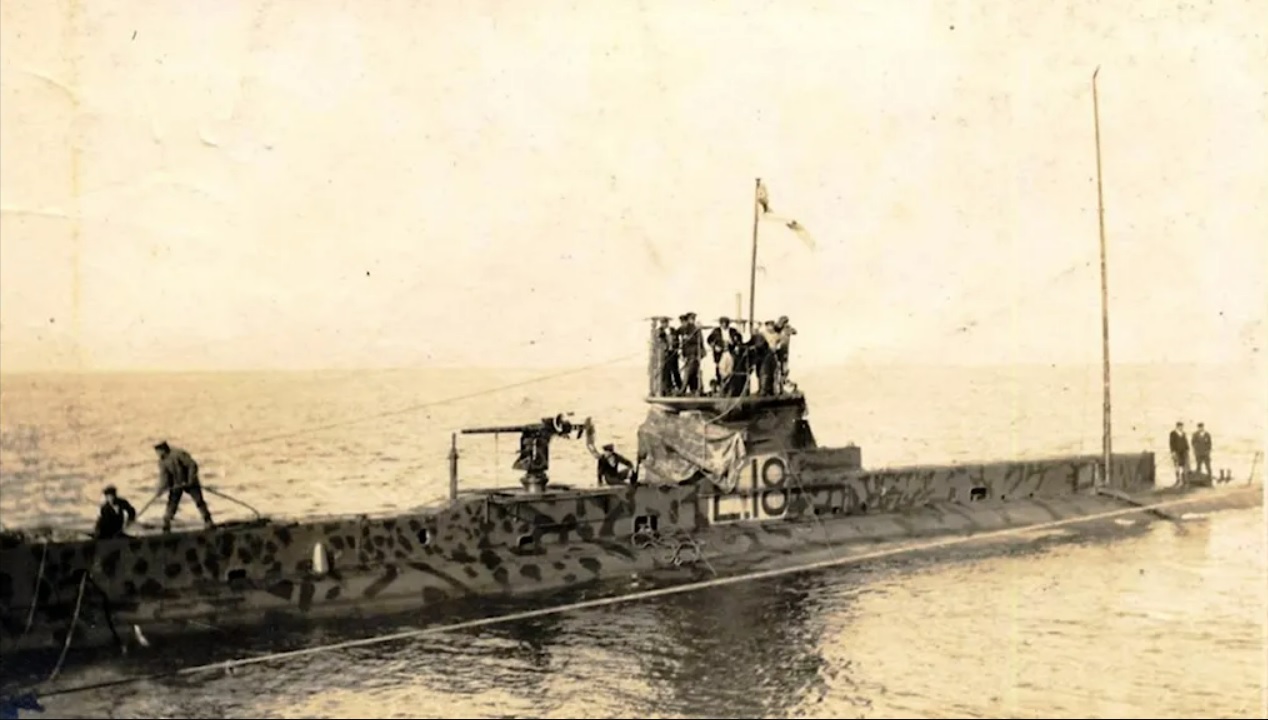

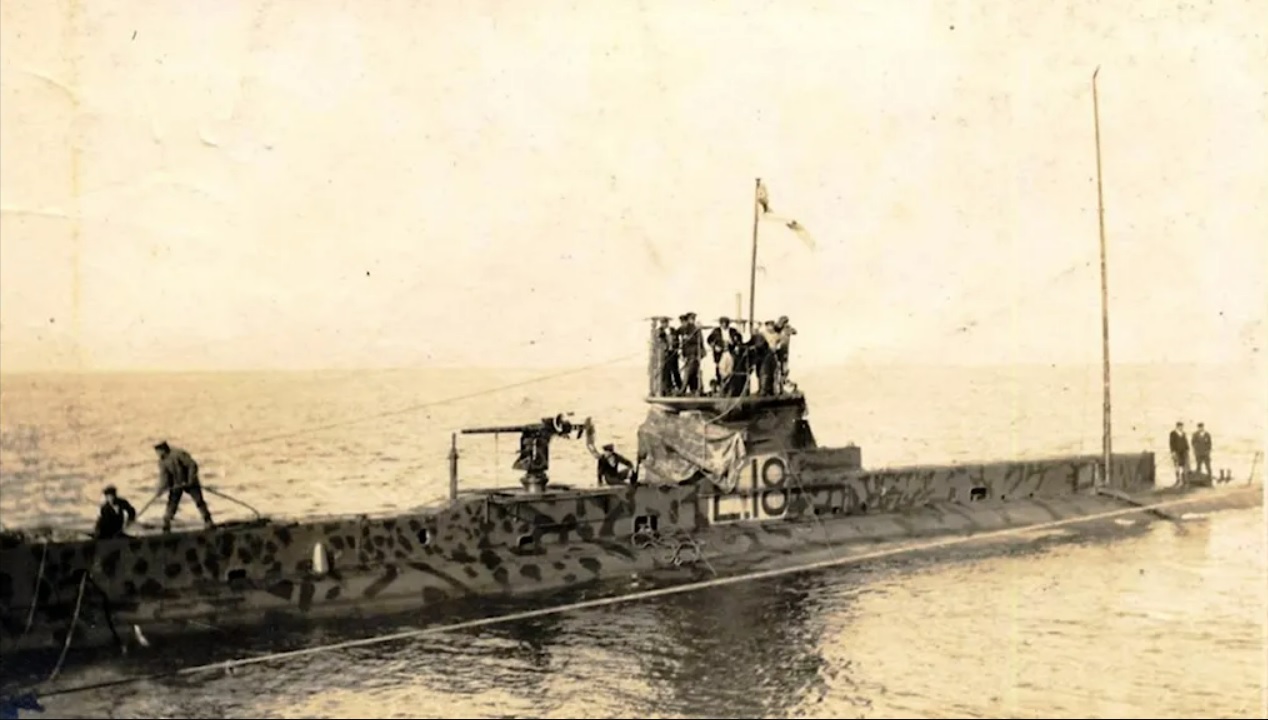

E18 Arriving off Dagerort, 12-9-1915. Note the extensive camouflage applied. Photo: Royal Navy Submarine Museum

They were assigned the steamers Cicero, Emilie, and Obsidian to serve as tenders and a home (away from home) for the British submariners and support staff.

By October, they waged a campaign to disrupt iron ore traffic from Lulea in Sweden to German ports and sank ten merchantmen over three weeks. The month ended with E-8 sinking Prinz Adalbert when a spread of torpedoes sent her magazine to the heavens, carrying almost 700 of the cruiser’s complement with it. The following month, E-19 hit the German light cruiser Undine with two torpedoes, sinking her south of the southern Swedish town of Trelleborg.

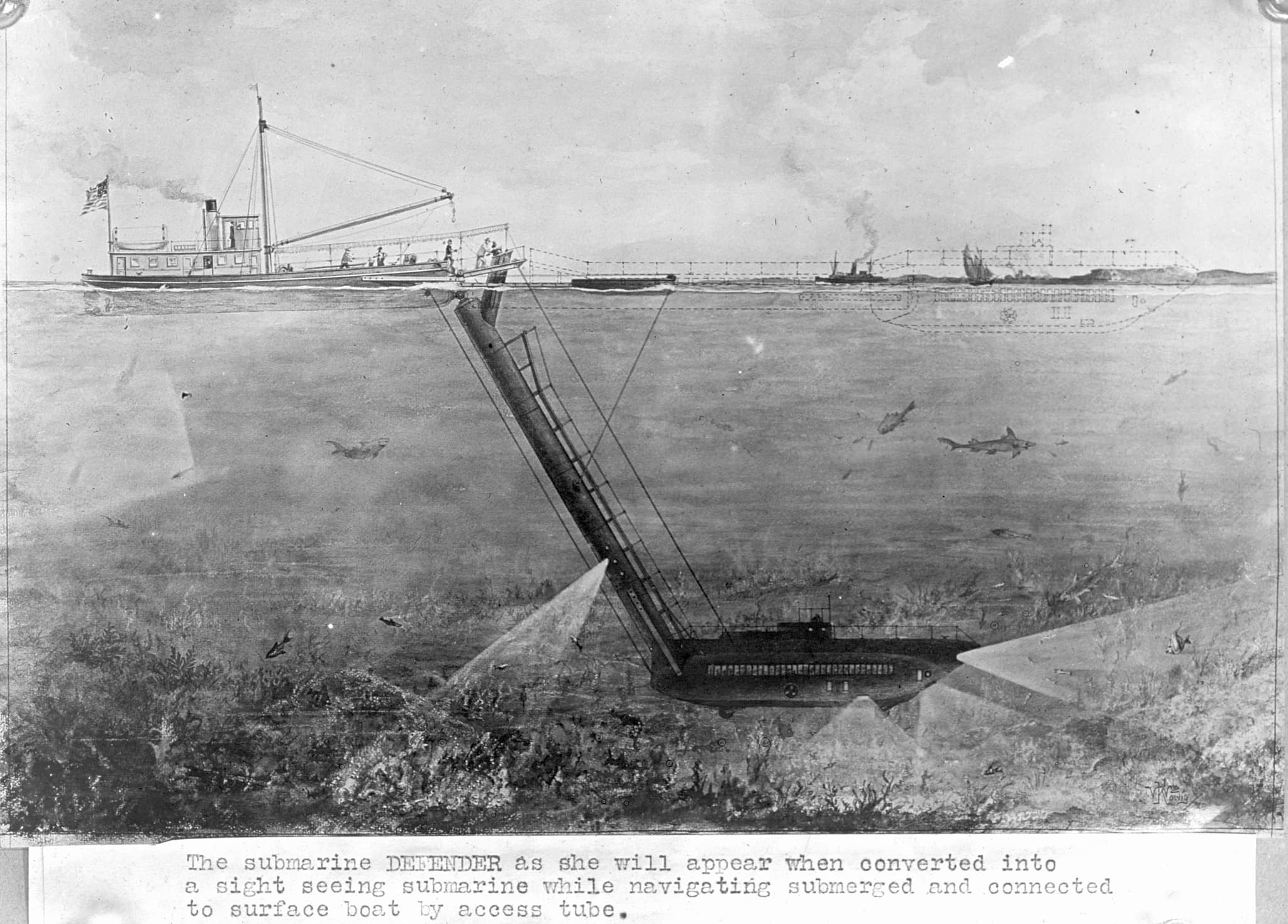

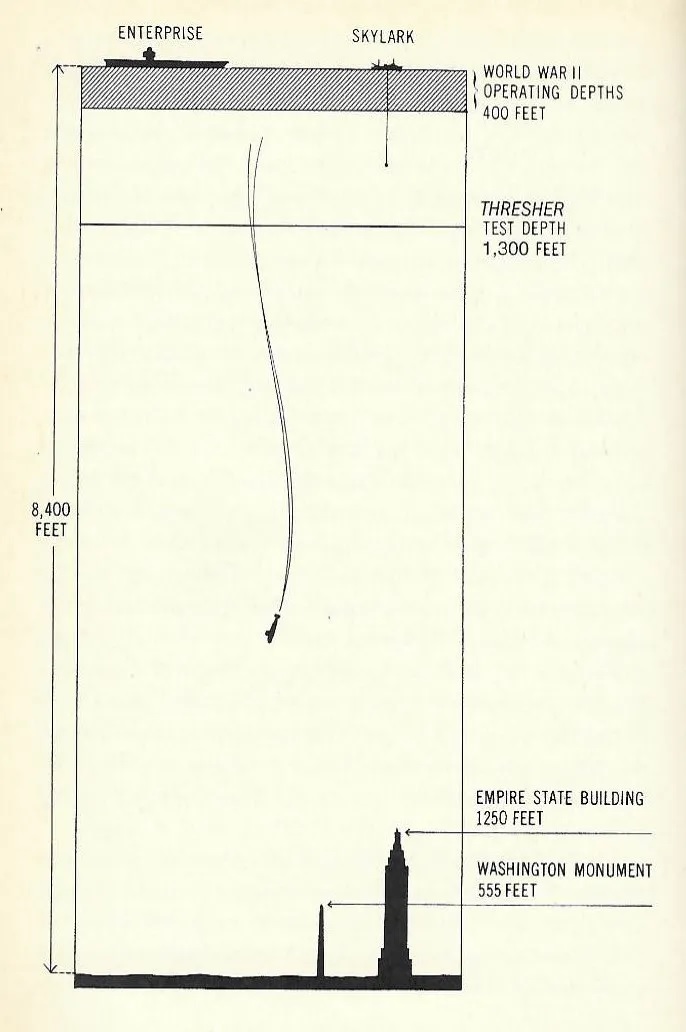

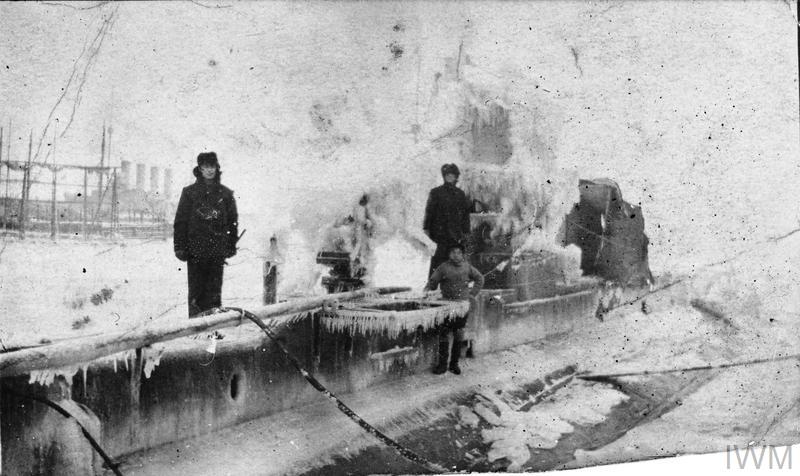

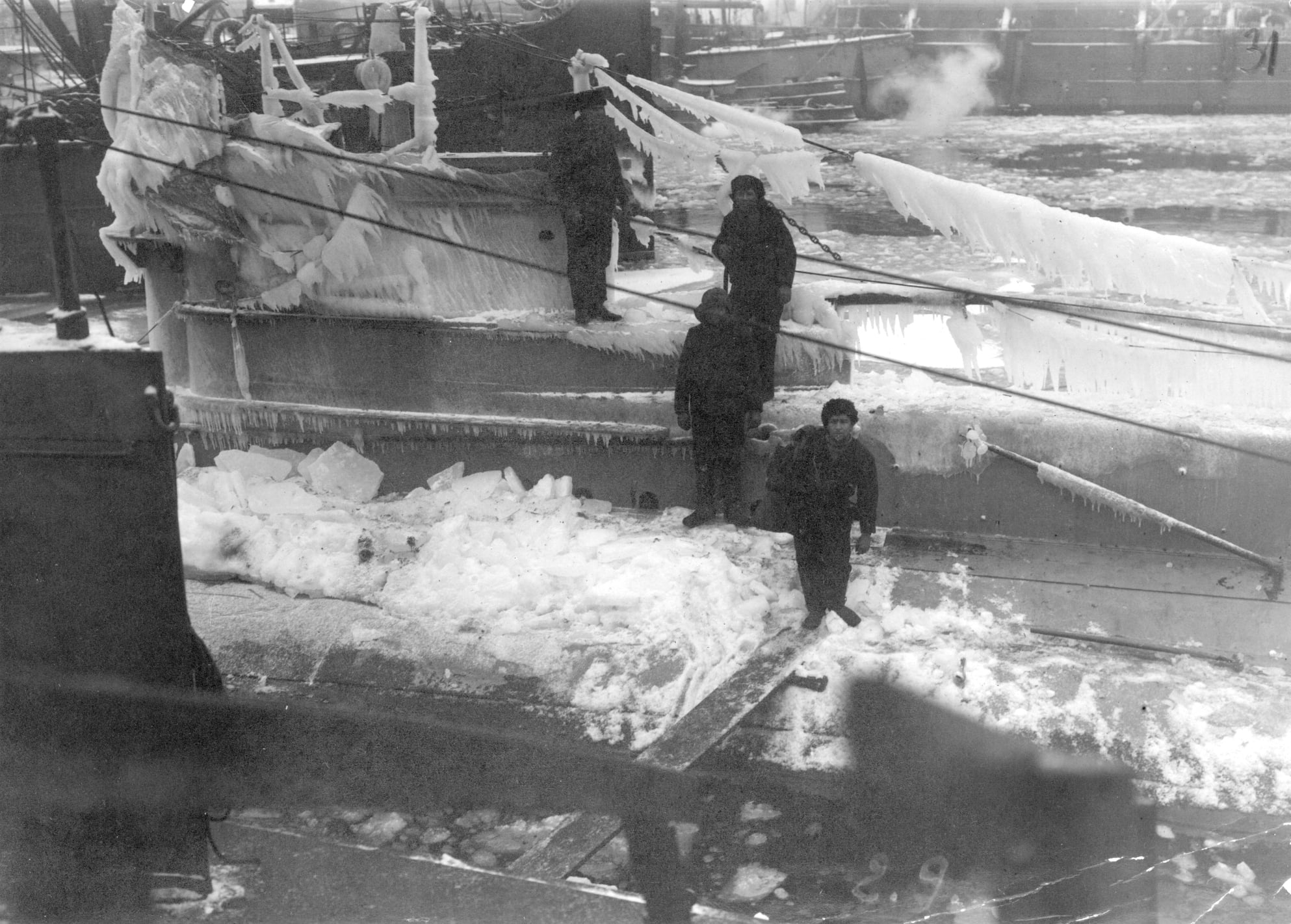

While the five Es were busy, a further four smaller C-class boats (our C27 along with HMS C26, C32, and C35) were given the mission to join them. However, since it was unlikely they could force the Oresund, they were stripped of as much weight as possible to give them increased buoyance, then towed to Archangel in the frozen Russian North, and finally taken by barge down the Dvina and across Lakes Onega and Ladoga to the Gulf of Finland where they would take the water once again and be ready to almost double the British submarine flotilla in the Baltic.

The thing is, this boondoggle, which sounded good on paper to someone, took almost 18 months to carry out and by the time the C-boats were ready for action in early 1917, the Tsar had been deposed, and things were getting downright weird in Russia. Nonetheless, the British boats were still as active as they could be, even while the now revolutionary Russian fleet was content to sit on its hands. As such, C32 was lost in October 1917 in the Gulf of Riga but claimed at least one German merchant sunk.

As the Bolsheviks swept to power in November 1917, and soon signed first a truce and then a peace with the Germans, the Kaiser’s troops started swarming through the Baltics and landing in Finland in March 1918. With the remaining British subs backed into a corner with no options, they made one final sortie to scuttle.

HMS E18 leaving Reval for the last time on May 25th, 1916

HMS E-18 had already been lost to German activity in May 1916, leaving E-1 and E-9 to be scuttled in the Gulf of Finland off the Harmaja Lighthouse on 3 April, followed by E-8 and C-26 on 4 April, and our C27 and C35 on 5 April. E-19 was sunk on 8 April. The supply ship Emilie was sunk on the northwest side of Kuivasaari on the 9th. The maintenance ships Cicero and Obsidian were sunk southwest of Bändare on the 10th, ending the carnage.

This left the flotilla’s 150~ remaining members to exfiltrate with the nominal help of the Reds back to Murmansk, where most soon became part of the British interventionist forces that would operate on the White Sea and the Dvina against the Reds well into 1919.

The flotilla’s senior officer, E-19‘s skipper CDR Francis Newton Allen Cromie, stayed behind in Petrograd where he was officially a naval attaché but nonetheless assumed the vacant portfolio of the British ambassador. There, he helped interface with assorted counter-revolutionary types, only to be killed by Cheka agents when the Reds raided the embassy in August 1918.

C-27‘s final commander, LT Douglas Carteret Sealy, survived the war and revolution but would be lost on HM Submarine H42 when she was rammed while submerged near Gibraltar by the “V” Class destroyer HMS Versatile in 1922.

For a deeper dive (see what we did there?) into the British Baltic boats, see Baltic Assignment: British Sub-Mariners in Russia 1914-1919, by Michael Wilson.

Epilogue

Of the other 35 C-class boats built for the Royal Navy that entered the war, several failed to emerge on the other side after the Armistice. As covered, C26, C27, C32, and C35 were scuttled in the Baltic to avoid capture, while C29 and C33 were lost in 1915 while on the U-boat Trap detail.

Other wartime losses included:

- HMS C31 was sunk by a mine off the Zeebrugge on 4 January 1915, lost with no survivors

-

HMS C16 sunk after being rammed at periscope depth by destroyer HMS Melampus off Harwich on 16 April 1917

-

HMS C17 collided with the destroyer HMS Lurcher the following month and sank.

-

HMS C34 was sunk by U-52 in the Shetlands while on the surface on 17 July 1917. Her sole survivor ended the war in a German POW camp.

-

HMS C3 was packed with explosives and rammed into the viaduct at Zeebrugge on 23 April 1918, blasted sky high, with her skipper earning the VC.

LT Richard Douglas Sandford VC HM Submarine C3, Zeebrugge Raid, 22 – 23 April 1918 IWM Q 104329

The two dozen enduring C-boats left on the Admiralty’s list in 1919 were soon disposed of, largely through sale for dismantling. They were just too obsolete for further use, even though the oldest hull in the batch had just 15 years on its frames.

HMS C4, converted in secret by D.C.B. Section at the RN Signals School at Portsmouth into an unmanned vessel controlled remotely by an operator in a nearby aircraft, was the only surviving C-class submarine not to be scrapped at the end of the Great War. Still, she only lingered until 1922 when she went to the breakers.

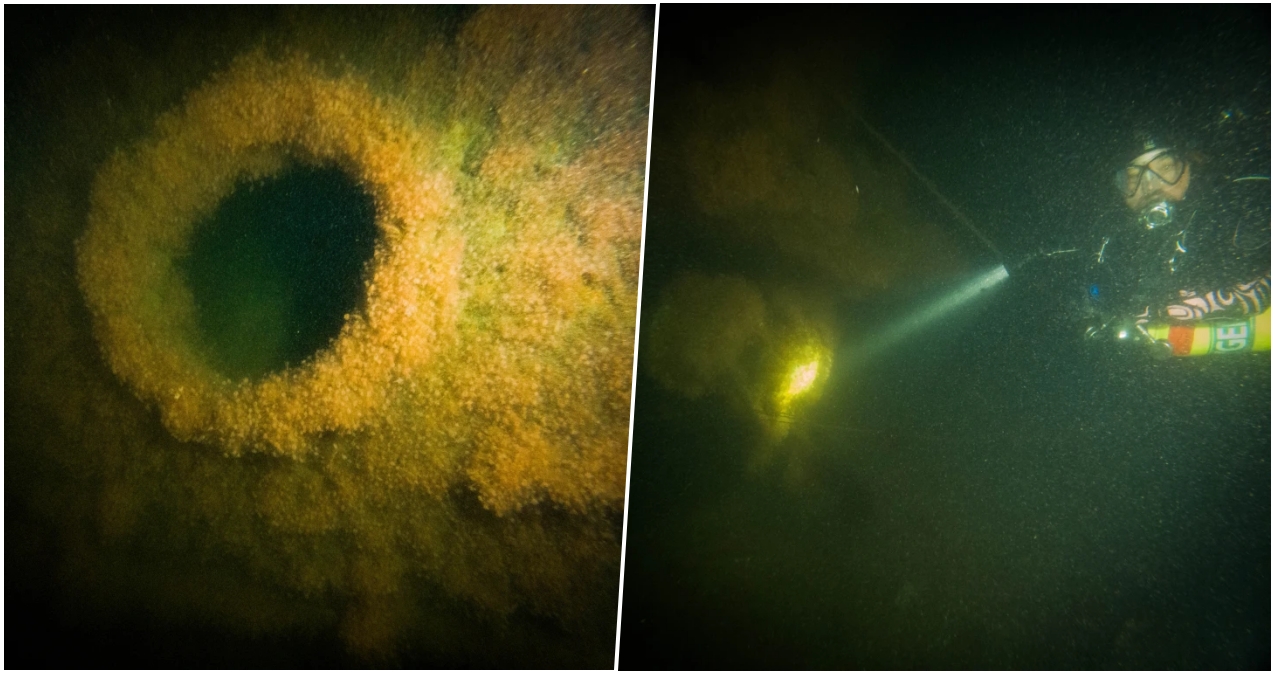

The wrecks of the British Baltic flotilla, our C27 included, have largely been found and well documented over the years, with some even raised for scrap or attempts to put back into service, with unsatisfactory results.

Today, the C-class is best remembered in a series of period maritime art that still stirs emotions.

“HMS Bonaventure and Submarines” circa 1911 by William Lionel Wyllie. RMG PW2083. Inscribed, as title, and signed by the artist, lower right. The ‘Bonaventure’ (1892) was a second-class protected cruiser converted to a submarine depot ship in 1907. This finished watercolor shows the ship in her 1911-14 condition. Both the ‘Bonaventure’ and the trawler tender on the left are flying large red flags, advising other vessels to keep clear of a submarine operating area. The submarine with the number ’61’, lying close to ‘Bonaventure’, is the ‘C31’, launched on 2 September 1909 and lost by unknown causes after leaving Harwich for the Belgian coast on 4 January 1915. What appears to be a practice torpedo is in the foreground and an unidentifiable submarine is on the left. As the circumstances indicate, the drawing is of an exercise off the English coast, probably in the Channel from the relatively high ground behind.

“Near the Dardanelles, English, and French warships in the harbor of Malta,” by Alexander Kircher, with C22 and C26 in the foreground.

“A fleet of submarines passing HMS Dreadnought,” by Charles Edward Dixon, circa 1909. The closest boat is HM Submarine C-14

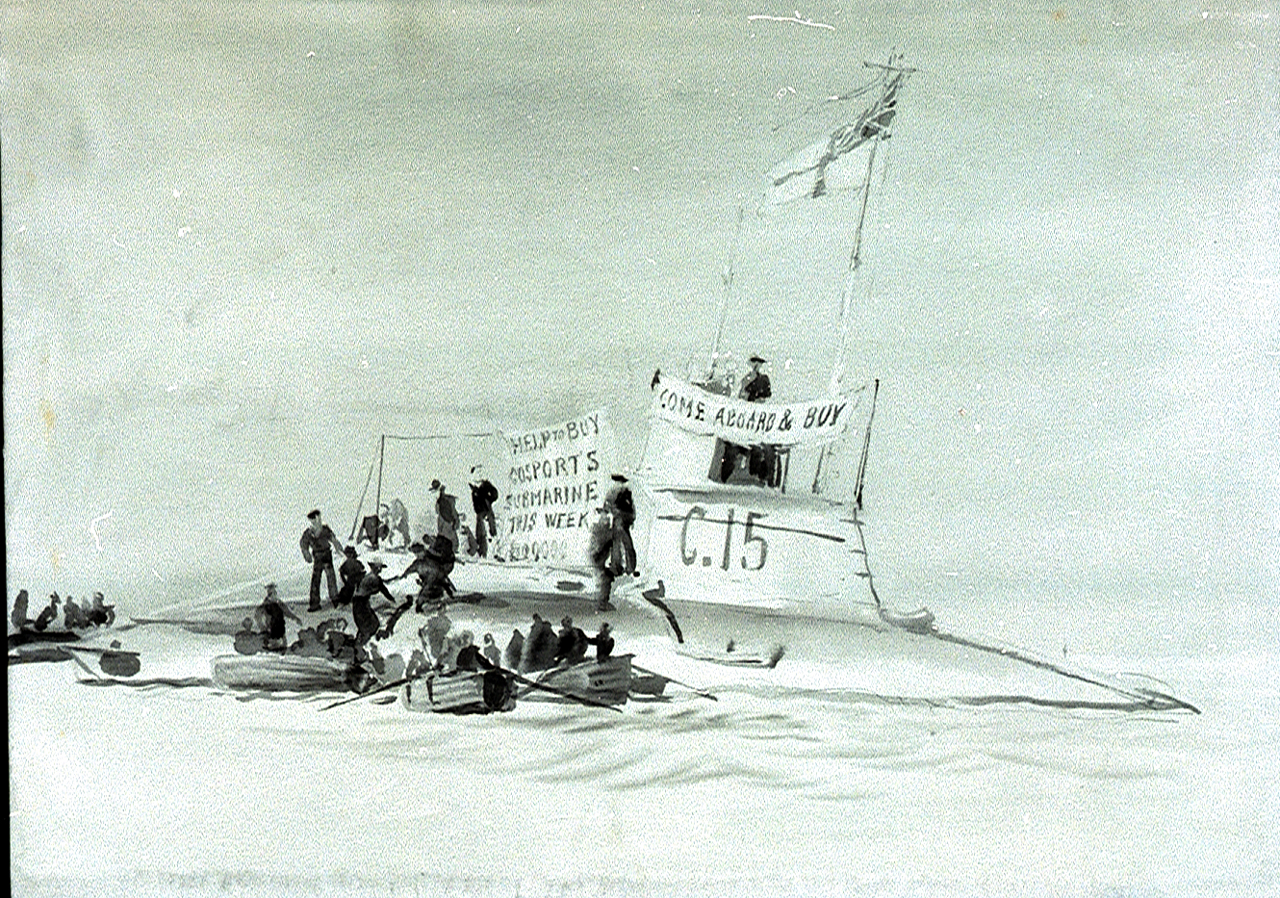

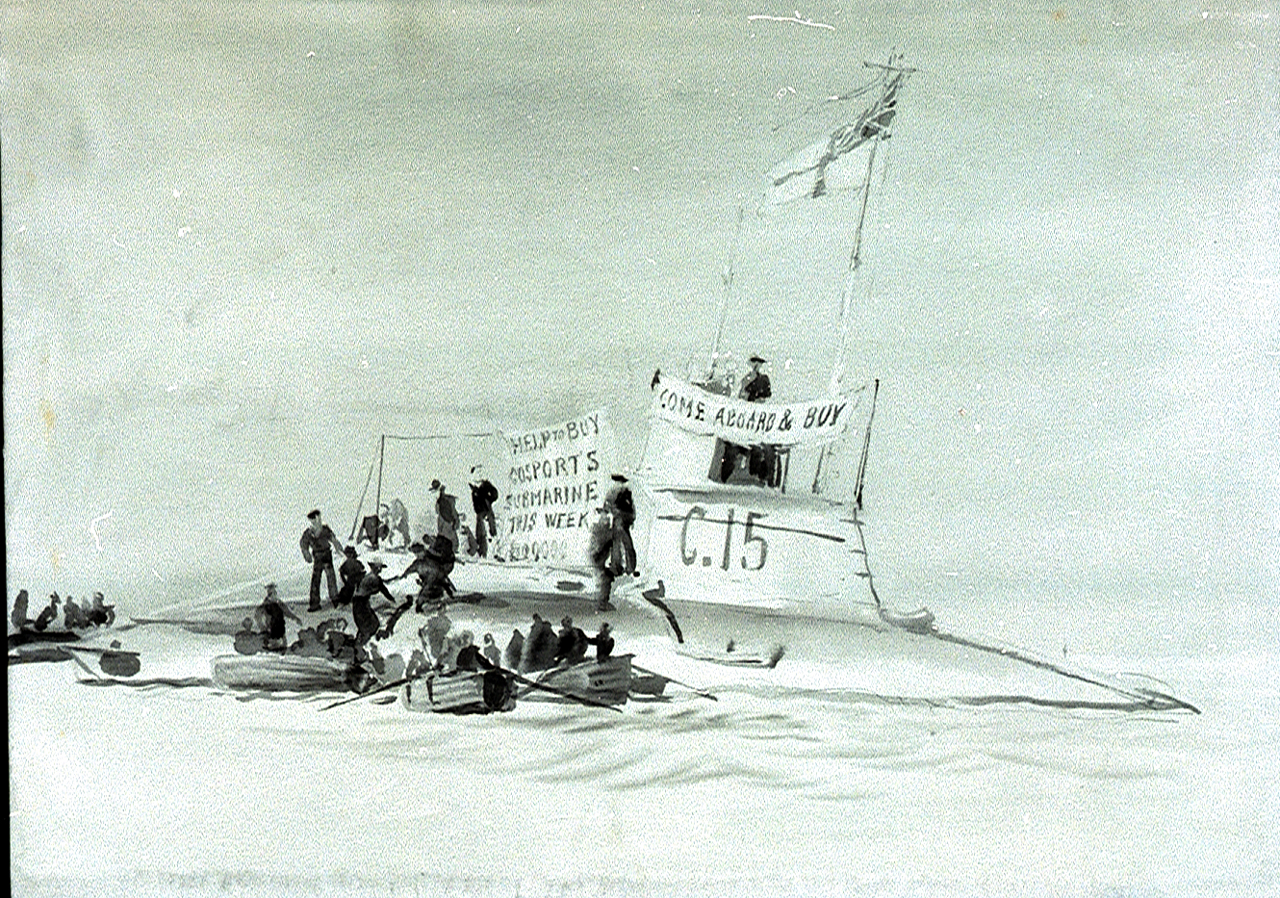

“The submarine ‘C15’ fundraising for the Gosport war effort” by William Lionel Wyllie. RMG PV3490

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!