Warship Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024: A Tough Tambor

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, Feb. 28, 2024: A Tough Tambor

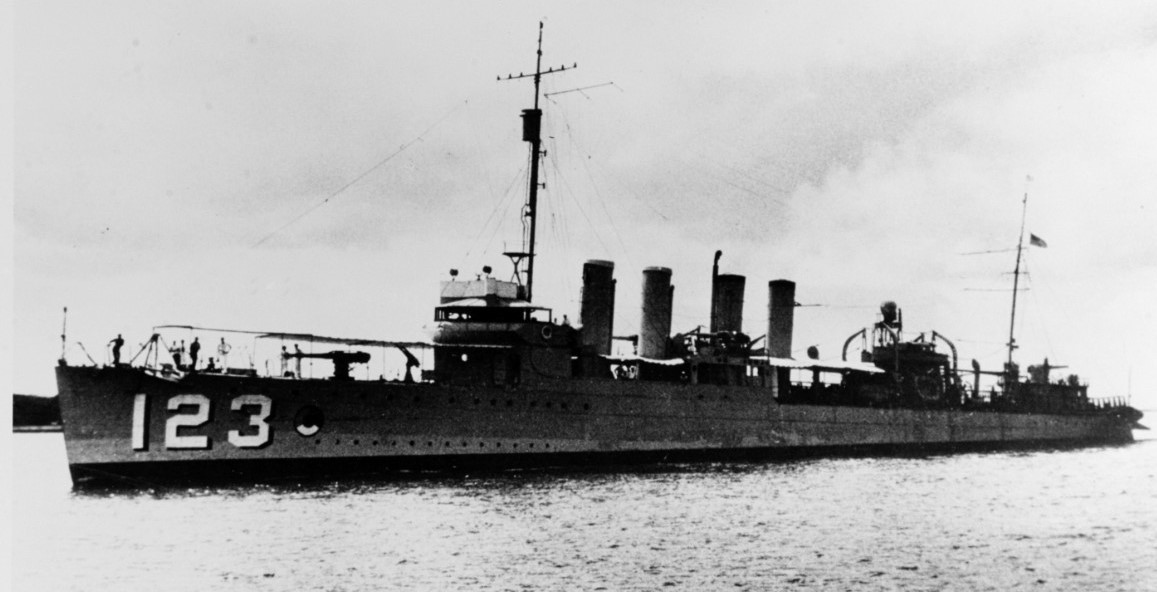

Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the U.S. National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-32217

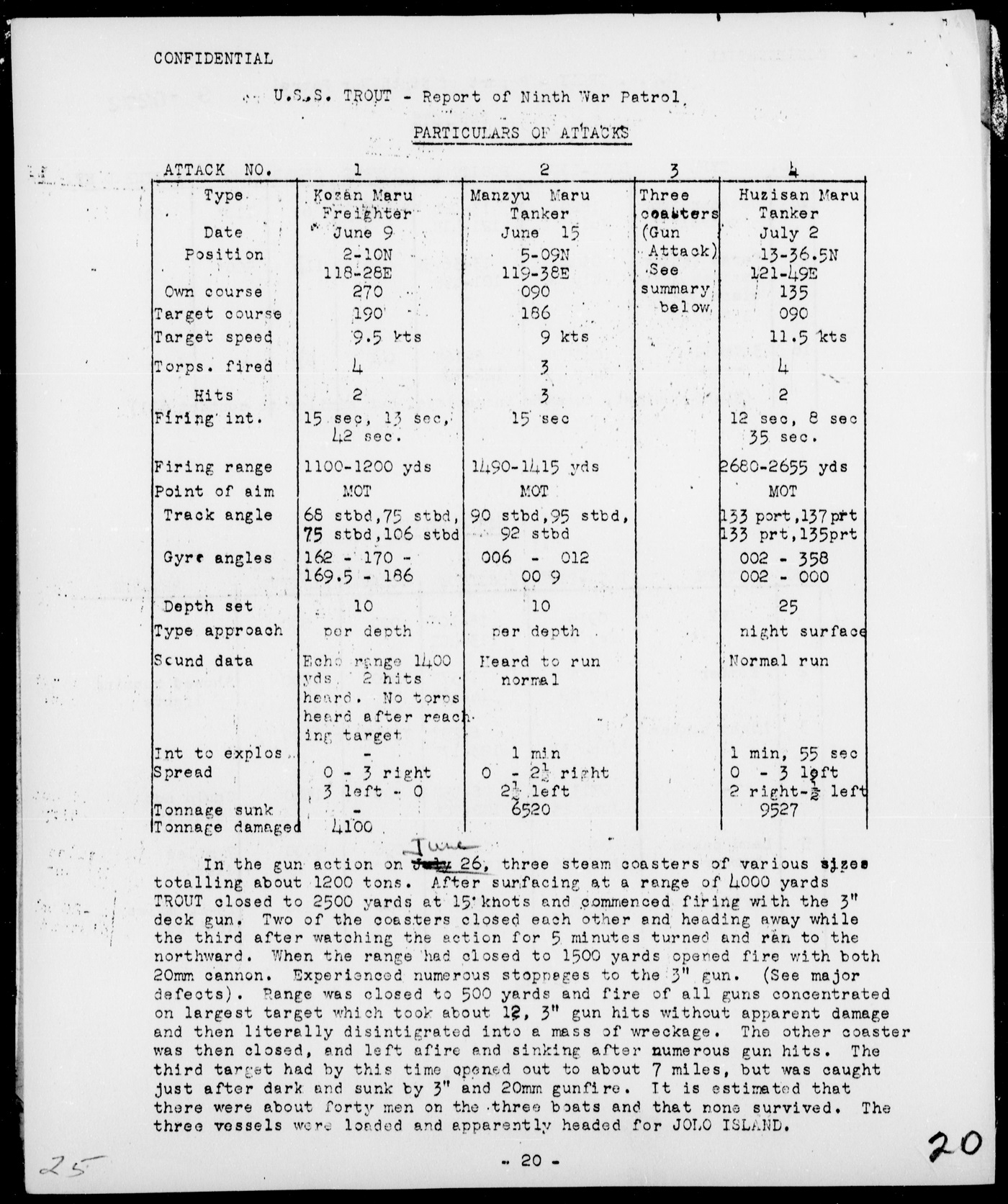

Above we see the Tambor-class fleet boat USS Trout (SS-202) as she returns to Pearl Harbor on 14 June 1942, just after the Battle of Midway. She is carrying two Japanese prisoners of war from the sunken cruiser Mikuma. Among those waiting on the pier are RADM Robert H. English and “the boss,” Admiral Chester W. Nimitz. Note the pair of .30-06 Lewis guns on Trout’s sail, flanking her periscope shears.

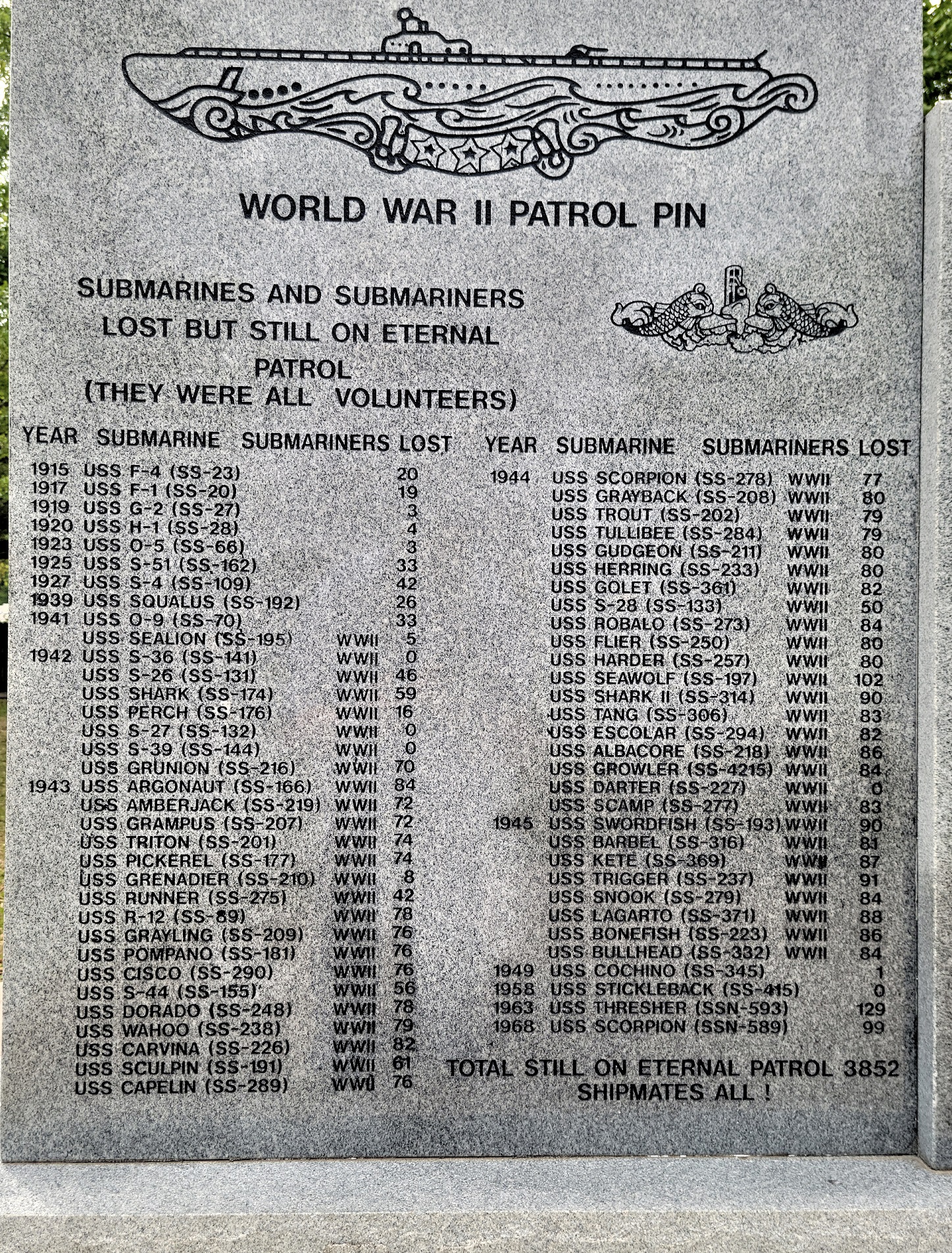

Trout is believed lost with all hands, 80 years ago this month, around 29 February 1944, off the Philippines while on her 11th war patrol.

The Tambors

The dozen Tambors, completed in a compressed 30-month peacetime period between when USS Tambor (SS-198) was laid down on 16 January 1939 and USS Grayback (SS-208) commissioned on 30 June 1941, are often considered the first fully successful U.S. Navy fleet submarines. This speedy construction period was in large part due to the fact they were completed in three different yards simultaneously.

Some 307 feet long with a 2,375-ton submerged displacement, they carried 10 21-inch torpedo tubes (six forward, four aft) with a provision for 24 torpedoes (or 48 mines), as well as a small 3″/50 deck gun augmented by a couple of Lewis guns and the occasional .50 cal. They enjoyed a central combat suite with a new Torpedo Data Computer and attack periscope.

With an engineering suite of four diesel engines driving electrical generators and four GE electric motors drawing from a pair of 126-cell Sargo batteries, they could sail for an amazing 10,000nm at 10 knots on the surface and sprint for as much as 20 knots while on an attack. Further, they had strong hulls, designed for 250-foot depths with a possible 500-foot redline crush. They also had updated habitability for 70-day patrols including freshwater distillation units and air conditioning. A luxury!

Meet Trout

Our boat was one of four Tambors constructed by the historic Portsmouth Navy Yard, built side-by-side with sister USS Triton (SS-201). Trout was the first boat to carry the name in the U.S. Navy and, laid down on 28 August 1939, was launched on 21 May 1940 after a nine-month gestation period.

Trout (SS-202) bow view at fitting out the pier, 10 July 1940 at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine, via ussubvetsofworldwarii.org through Navsource.

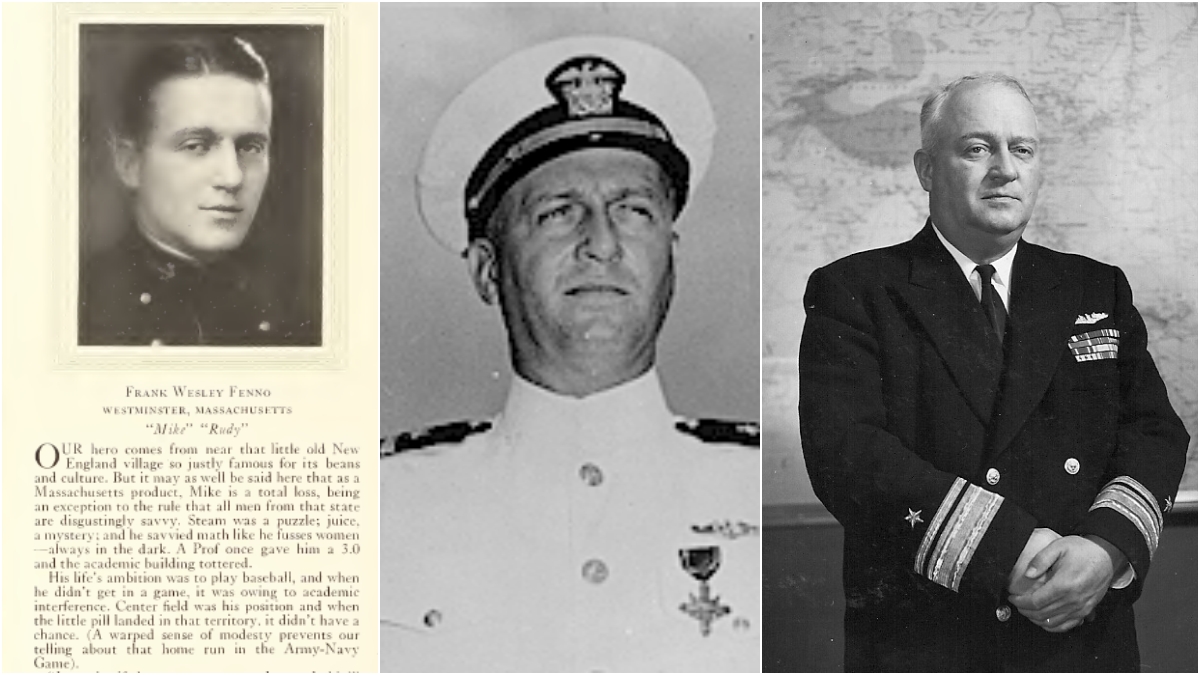

Commissioned on 15 November 1940, LCDR Frank Wesley “Mike” Fenno, Jr., (USNA 1925), formerly of the “Sugar Boats” S-31 and S-37, was in command.

Following shakedowns on the East Coast, Trout sailed through “The Ditch” and joined five sister boats in Submarine Division 62, based at Pearl Harbor, where she arrived in August 1941 as part of the big build-up in the tense Pacific.

War!

On 7 December 1941, one of Trout’s sisters, USS Tautog (SS-199), was tied up at the Submarine Base at Pearl Harbor and her .50 cals and Lewis guns were credited with downing at least one Japanese plane during the attack that morning.

As for the other five Tambors operating at Pearl?

They were all out on patrol, our Trout included, which was off the then-unknown atoll of Midway. That night, she spotted the Japanese destroyers Sazanami and Ushio as they shelled the American base there but was unable to successfully attack them.

Ending what turned out to be her 1st War Patrol on 20 December in the still-smoking battle-scarred base at Pearl, Trout, after landing most of her torpedoes and ballast, was ordered to take aboard 3,517 rounds of badly needed 3-inch AA ammunition and sortie out on her 2nd War Patrol on 12 January 1942, bound run the Japanese blockade to the besieged American forces on the “Rock” Corregidor in the Philippines. Over 45 days, nine American subs, Trout included, made the dangerous run to the last U.S. stronghold in Luzon.

Arriving at Corregidor on 6 February after a brief brush with a Japanese subchaser, Trout unloaded her shells and then took on a ballast of 20 tons of gold bars and silver pesos (all the paper money in the islands had already been burned), securities, mail, and United States Department of State dispatches, which she dutifully brought back to Pearl on 3 March. However, on the way she took the time to chalk up her first confirmed “kill” of the war: the Japanese auxiliary gunboat Chuwa Maru (2719 GRT), sent to the bottom about 55 nautical miles from Keelung, Formosa on 9 February.

She arrived back in Pearl Harbor to unload her precious cargo.

USS Trout (SS-202) approaches USS Detroit (CL-8) at Pearl Harbor in early March 1942, to unload a cargo of gold that she had evacuated from the Philippines. The gold had been loaded aboard Trout at Corregidor on 4 February 1942. NH 50389

USS Trout (SS-202) coming alongside USS Detroit (CL-8) at Pearl. Note details of the submarine’s fairwater, and .30 caliber Lewis gun mounted aft of the periscope housing. NH 50388

USS Trout (SS-202) At Pearl Harbor in early March 1942, unloading gold bars which she had evacuated from Corregidor. 80-G-45971

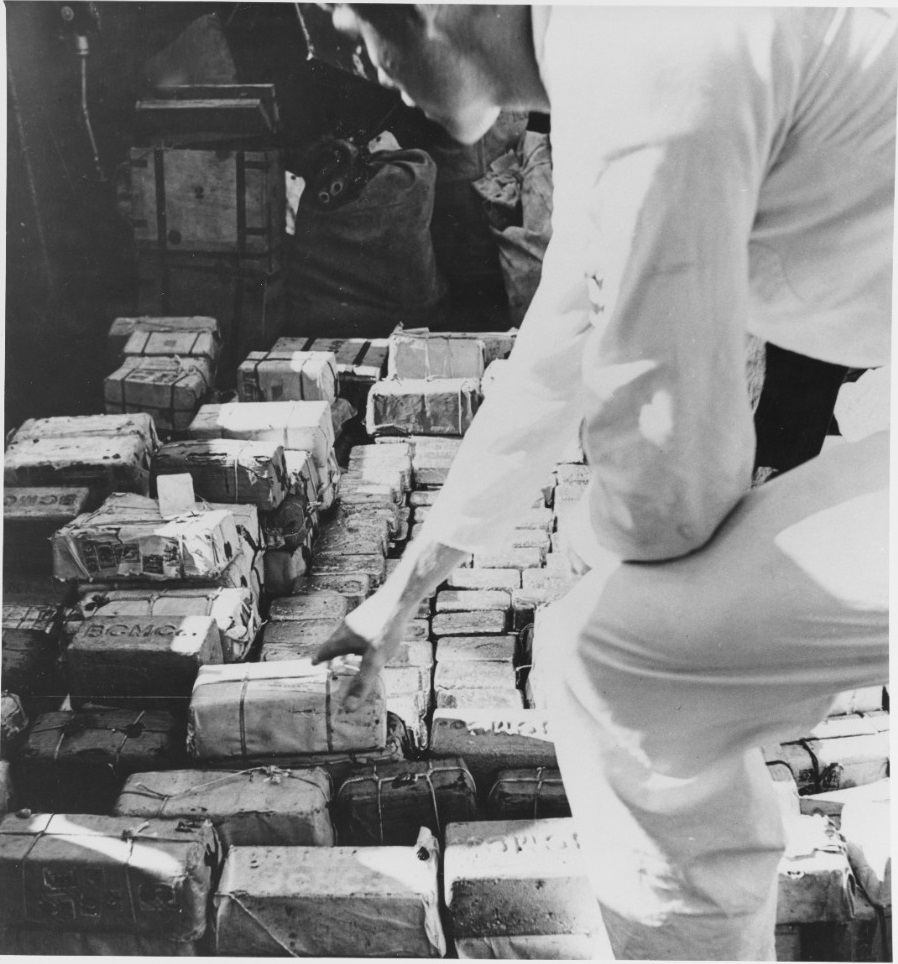

USS Trout (SS-202): gold bars that Trout carried from Corregidor to Pearl Harbor. Photographed as the gold was being unloaded from the submarine at Pearl Harbor in early March 1942. 80-G-45970

Sailing for her 3rd War Patrol on 24 March, she was ordered to take the war to Tokyo and haunt the Japanese home waters. Trout fulfilled that mandate and logged damaging attacks on the tanker Nisshin Maru (16801 GRT) and Tachibana Maru (6521 GRT), as well as sending the Uzan Maru (5019 GRT) and gunboat Kongosan Maru (2119 GRT) to the bottom before returning to Pearl in early May.

At the time Trout had logged the most successful U.S. Navy submarine war patrol to date and she was given credit for 31,000 tons sunk and another 15,000 tons damaged.

Midway

Her 4th War Patrol was to participate in the fleet action that is known today as the Battle of Midway– Trout’s old December 7th stomping grounds. She left Pearl on 21 May in company with her sisters, USS Tambor, and USS Grayling, to join the 12-submarine Task Group 7.1, the Midway Patrol Group.

From her war diary of the battle, which included chasing down a crippled Japanese battleship which turned out to be the lost 14,000-ton Mogami class heavy cruiser Mikuma. She rescued two Japanese survivors from said warship, Chief Radioman Hatsuichi Yoshida and Fireman 3rd Class Kenichi Ishikawa, on 9 June. Some of the very few IJN POWs in American custody at the time, Trout was ordered to return to Pearl with her waterlogged guests of the Emperor’s Navy, arriving there five days later to an eager reception committee.

Battle of Midway, June 1942. The burning Japanese heavy cruiser Mikuma, photographed from a U.S. Navy aircraft during the afternoon of 6 June 1942, after she had been bombed by planes from USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Hornet (CV-8). Note her third eight-inch gun turret, with the roof blown off and barrels at different elevations, Japanese Sun insignia painted atop the forward turret, and wrecked midship superstructure. 80-G-457861

Japanese prisoners being removed from USS Trout (SS 202) at Pearl Harbor Submarine Base, Territory of Hawaii Shown: Three officers standing together are: Commander Jack Haines; Commander Norman Ives, and Commander O’Leary. Photographed 1942. 80-G-32213

Japanese prisoners being removed from USS Trout (SS 202) at Pearl Harbor Submarine Base, Territory of Hawaii Shown: Japanese Prisoner. Photographed 1942. 80-G-32212

With four patrols under his belt, including the successful 3rd patrol, the Corregidor ammo run/gold return, and the Midway POWs, FDR directed that LCDR Fenno be awarded the Army Distinguished Service Cross, while the rest of the crew received the Army Silver Star Medal. Fenno also racked up two Navy Crosses and, ordered to take command of the building Gato-class fleet boat USS Runner (SS-275), Trout’s plank owner skipper left for New London.

He was replaced by LCDR Lawson Paterson “Red” Ramage (USNA 1931) who had earned a Silver Star earlier in the year as the diving officer on Trout’s sister, USS Grenadier (SS-210), during the sinking of the 14,000-ton troopship Taiyō Maru.

Back in the War

Red Ramage and Trout left Pearl on the boat’s 5th War Patrol on 27 August, bound for the Japanese stronghold of Truk, where she was able to sink the net layer Koei Maru (863 GRT) and damage the 20,000-ton light carrier Taiyo, knocking the latter out of the war for over two months and forced her back to Kure for repairs.

Damaged by a Japanese airstrike that knocked out her periscopes, Trout cut her patrol short and made for Freemantle.

Repaired, Trout’s 6th War Patrol, in the Solomons in October-November, proved uneventful.

Red Ramage then took Trout on her 7th Patrol, leaving Fremantle four days after Christmas 1942, headed for the waters off Borneo. This long (11,000-mile, 58-day) patrol saw the boat damage two large (16-17,000 ton) tankers as well as two small gunboats and sink a pair of coastal schoolers. Combat included a running gunfight with the tanker Nisshin Maru on Valentine’s Day 1943 which left 10 members of Trout’s crew injured.

Trout’s 8th War Patrol, a minelaying run off Japanese-occupied Sarawak, Borneo in March-April, ended Red Ramage’s tour with our boat, and he left Freemantle bound for Portsmouth where he would oversee the building, outfitting, and first two (very successful) war patrols of the new Balao-class submarine USS Parche (SS-384).

Trout’s final skipper would be LCDR Albert “Hobo” Hobbs Clark (USNA 1933) who had been Trout’s Engineering officer on several of her early war patrols before serving on the staff of SubRon 6. He rejoined his former boat as “the old man” on 4 May 1943, just shy of his 33rd birthday. He would not see his 34th.

Trout was ordered back to the occupied Philippines as part of LCDR Charles “Chick” Parsons’s “Spy Squadron” of 19 submarines– including several Tambors— which delivered 1,325 tons of supplies in at least 41 missions to local guerrillas between December 1942 and New Years Day 1945, with an emphasis on medicine, weapons, ammunition, and radio gear.

Trout’s 9th War Patrol, from 26 May to 30 July 1943, saw two successful “special missions” landing agents and supplies in Mindanao well as conducting four attacks on Japanese surface ships, claiming some 17,247 tons sunk. Post-war the only confirmed sinking from this patrol was the freighter Isuzu Maru (2866 GRT), sunk 2 July.

As for the Spyron missions accomplished by Trout on this patrol, these included recovering Chick Parsons himself along with survivors of the Bataan Death March, who had escaped the hellish Davao POW camp, and delivering them to Australia where they were able to tell the world of what they had endured.

Details of Trout’s two Spyron missions, via the 7th Fleet Intelligence Section report:

Special mission accomplished. 12 June 1943.

Submarine: USS Trout (SS-202)

Commanding Officer: A. H. Clark

Mission: To deliver a party of six or seven men, funds ($10,000), and 2 tons of equipment and supplies to a designated spot on Basilon Island to establish a secret intelligence unit in the Sulu Archipelago and Zamboanga area; to establish coast watcher net in the area and for surveying purposes, and to arrange for delivery of extra supplies to guerrilla units.Special Mission accomplished 9 July 1943

Submarine: USS Trout (SS-202)

Commanding Officer: A. H. Clark

Mission: To land a party of two officers and three men, together with supplies and ammunition off Labangan, Pagadian Bay, on the South Mindanao Coast. In addition to the above, Trout picked up Lt. Comdr. Parsons and four U.S. Naval officers and reconnoitered the area southeast of Olutanga Island (South Coast of Mindanao, P.I.).

Leaving Freemantle again just three weeks later on her 10th War Patrol, Trout again returned to the Philippines where she patrolled the Surigao and San Bernardino straits. She would fight an epic surface engagement, pirate style, with a Japanese trawler during this patrol.

As noted by DANFS:

On 25 August, she battled a cargo fisherman with her deck guns and then sent a boarding party on board the Japanese vessel. After they had returned to the submarine with the prize’s crew, papers, charts, and other material for study by intelligence officers, the submarine sank the vessel. Three of the five prisoners were later embarked in a dinghy off Tifore Island.

A happy patrol, she would go on to sink the transports Ryotoku Maru (3438 GRT) and Yamashiro Maru (3427 GRT) back-to-back on 23 September before returning to Pearl Harbor, and from there, a much-needed trip to Mare Island for a four-month shipyard overhaul.

In her first ten patrols, Trout claimed 23 enemy ships, giving her 87,800 tons sunk, and damaged 6 ships, for 75,000 tons.

Leaving Mare Island for Pearl, on 8 February, Trout began her 11th and final war patrol. Topping off with fuel at Midway on the 16th she headed towards the East China Sea but was never heard from again.

Hobo Clark went down fighting and her 81 officers and men are listed on Eternal Patrol, with Clark and two other officers in the USNA’s Memorial Hall.

As detailed by DANFS:

Japanese records indicate that one of their convoys was attacked by a submarine on 29 February 1944 in the patrol area assigned to Trout. The submarine badly damaged one large passenger-cargo ship and sank the 7,126-ton transport Sakito Maru [which was carrying the Japanese 18th Infantry Regiment, of which 2,500 were lost]. Possibly one of the convoy’s escorts sank the submarine. On 17 April 1944, Trout was declared presumed lost.

It is thought that she was sunk by the destroyer Asashimo in conjunction with fellow tin cans Kishinami and Okinami.

Trout received 11 battle stars for World War II service and the Presidential Unit Citation for her second, third, and fifth patrols.

Trout is on the list of 52 American submarines lost in the conflict, along with twin sister Triton and classmates Grampus, Grayling, Grayback, Grenadier, and Gudgeon.

Just five of 12 Tambors were still afloat on VJ Day, and the Navy quietly retried them for use as Reserve training ships and then disposed of even these remnants by the late 1950s.

Epilogue

The plans and war diaries for Trout are in the National Archives.

Her 2nd Patrol– the Corregidor sneak that brought in AAA shells and left with gold and silver– was turned into an episode of The Silent Service in the 1950s.

Of her two surviving skippers, Mike Fenno would go on to take USS Runner on her first two war patrols in 1943 and take USS Pampanito (SS-383) on her 4th in 1944, chalking up at least two additional Japanese Marus, before going on to command SubRon 24 (“Fenno’s Ferrets”) for the rest of the war. He went on to command Guantanamo Bay during the tense early Castro period and retired as a rear admiral in 1962.

Red Ramage likewise took other boats out after he left Trout and is famous for a July 1944 convoy attack on USS Parche in conjunction with USS Steelhead that went down in the history books as “Ramage’s Rampage,” after it sent five Japanese ships to the bottom. This earned Ramage the MoH. He retired as a vice admiral in 1969 and passed in 1990. Like Mike Fenno, he is buried at Arlington. In 1995, the Flight I Burke, USS Ramage (DDG-61)— which I worked on at Ingalls and sailed on her trials– was named in honor of “Red.”

The Navy recycled Trout’s name for a late-model diesel boat of the Tang class (SS-566). This second USS Trout was laid down on 1 Dec. 1949 at EB and at her launch she was sponsored by the widow of LCDR Albert H. Clark, the last commanding officer of the first USS Trout (SS-202), who was lost on the boat’s 11th war patrol in 1944 along with 80 other souls.

Here we see a P-2H Neptune of Patrol Squadron (VP) 16 as it flies over the Tang-class submarine USS Trout (SS-566), near Charleston, S.C., May 7, 1961. NHHC KN-2708

After serving during the Cold War and being transferred to Turkey, in 1992, the near-pristine although 40-year-old Trout was returned to U.S. Navy custody and then used as an experimental hull and acoustic target sub at NAWCAD Key West. She somehow survived in USN custody until 2008 when she was finally reduced to razor blades at Brownsville.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!