Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, June 28, 2023: The Tsar’s Jutland Veteran

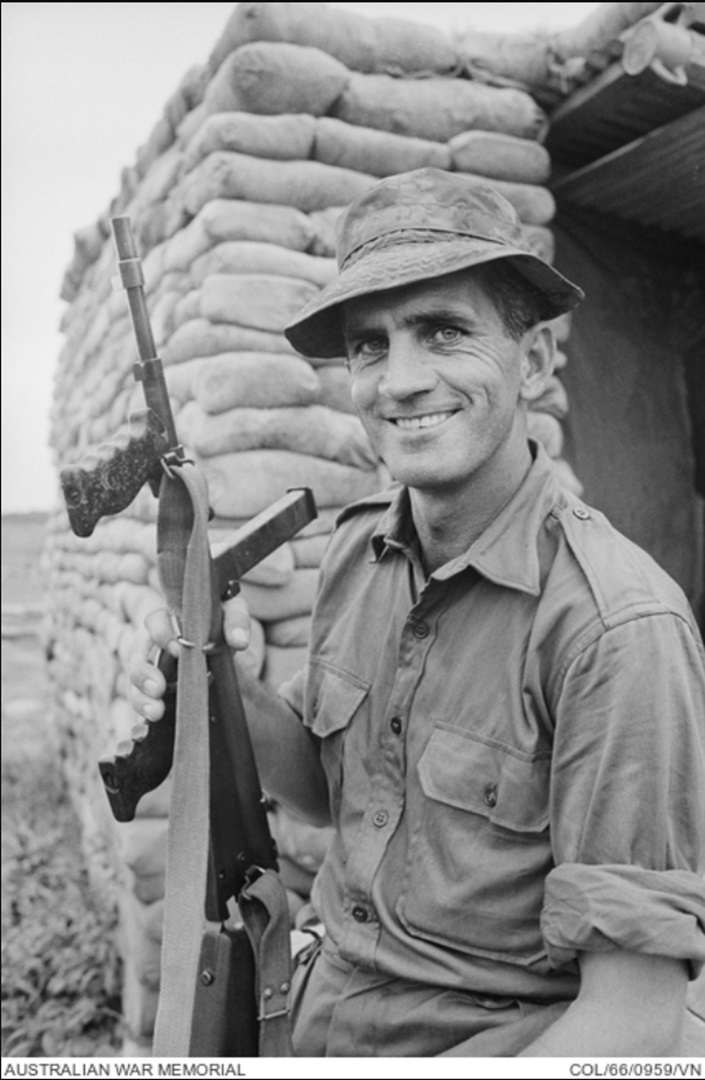

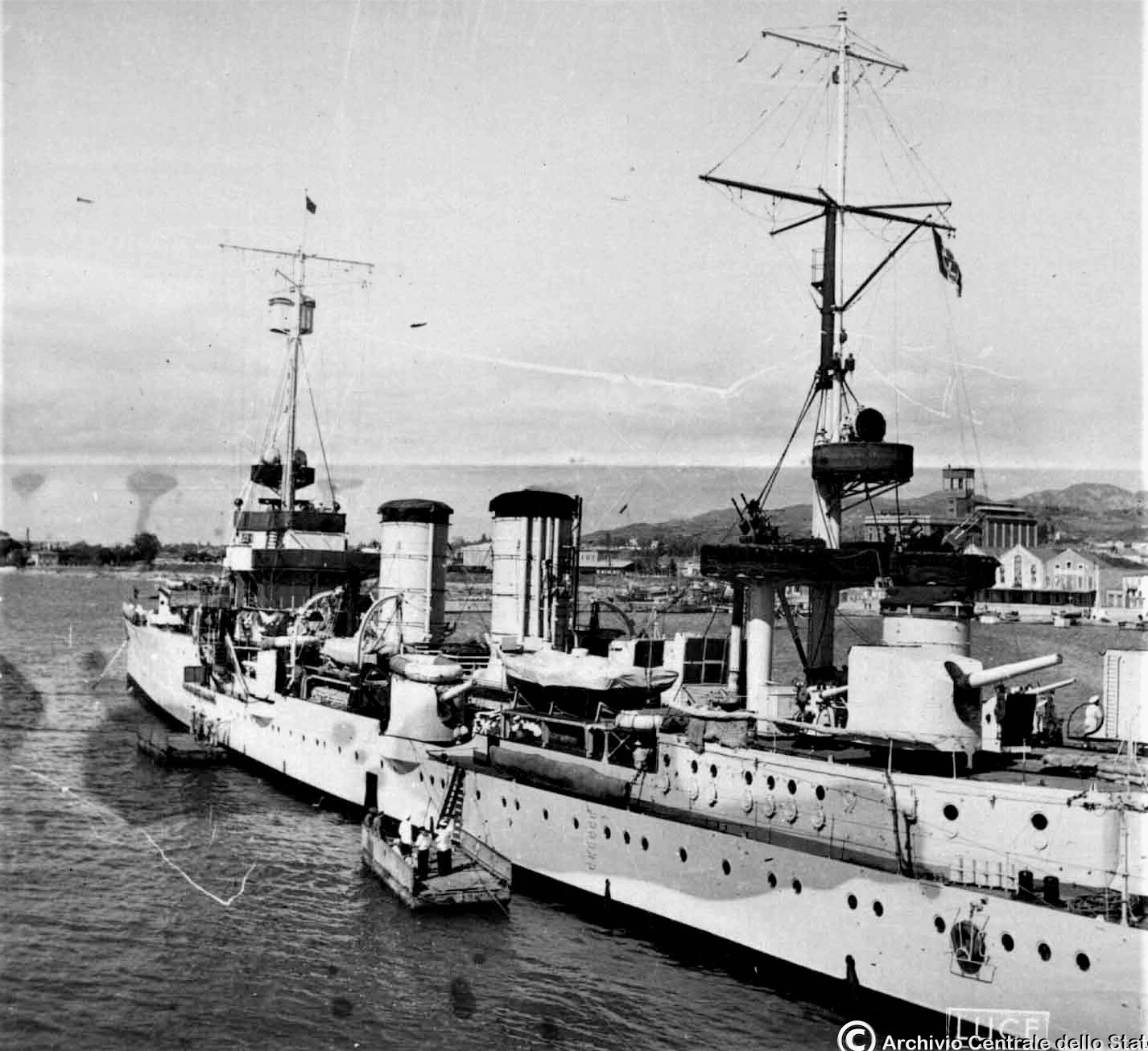

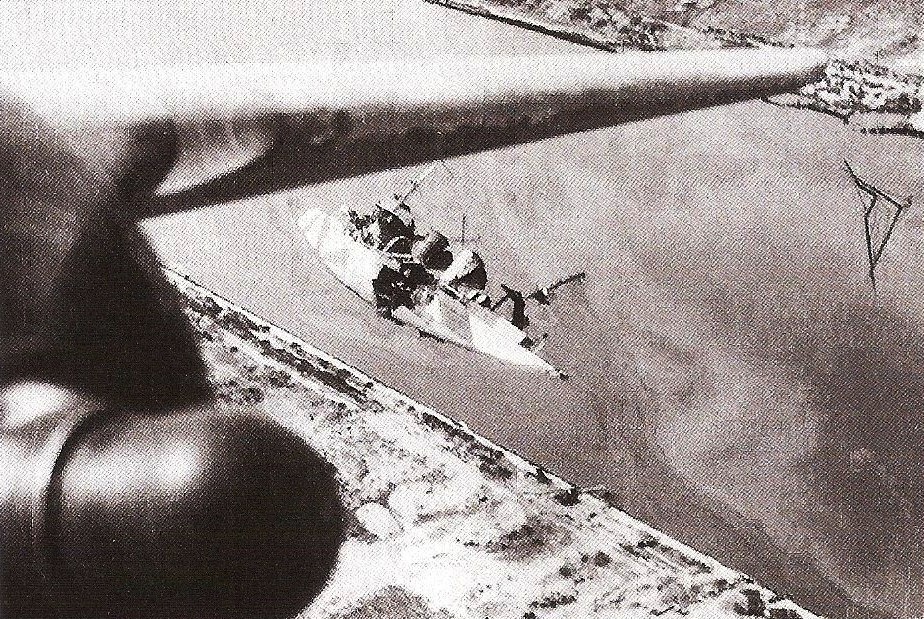

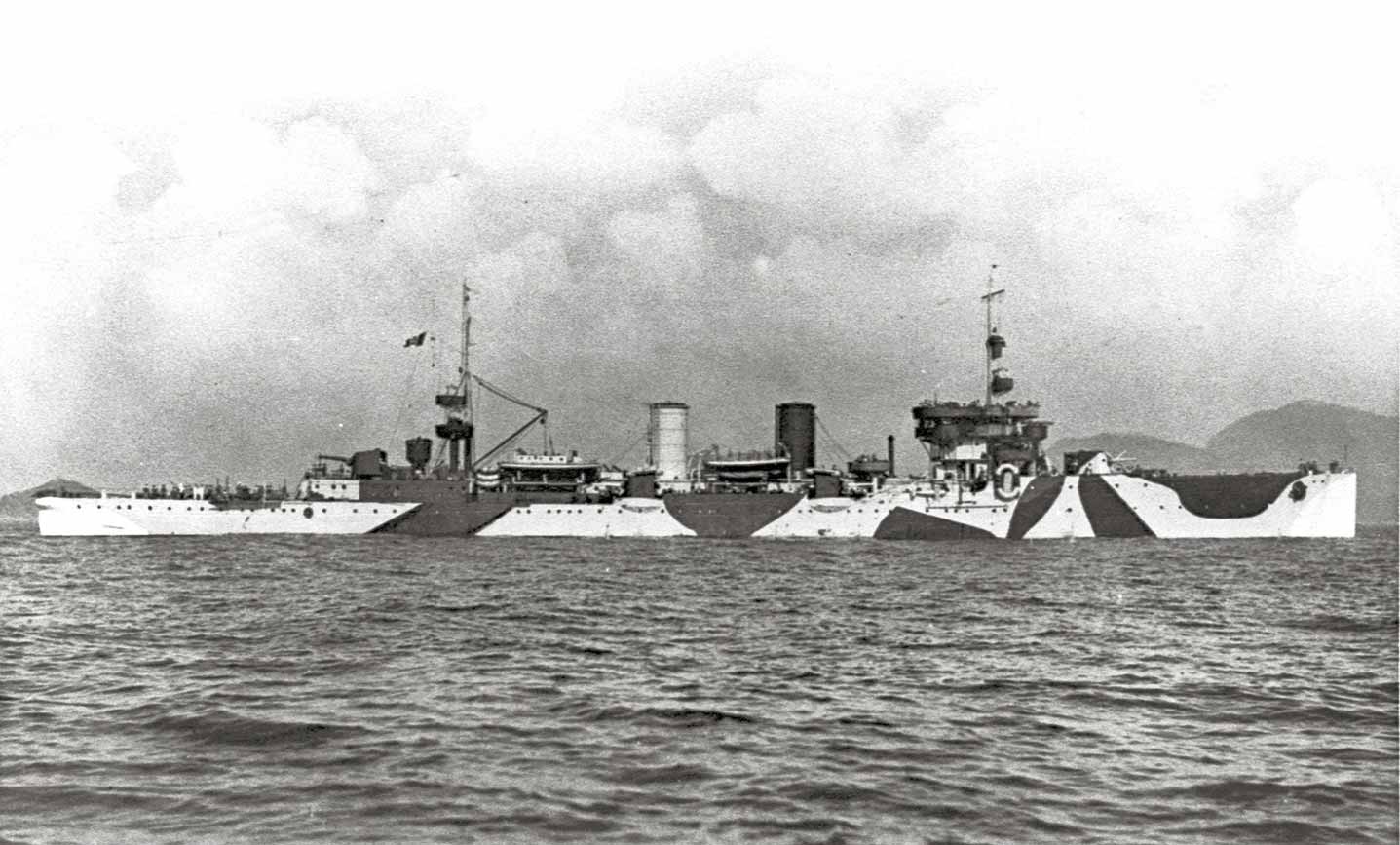

Archivio Centrale dello Stato

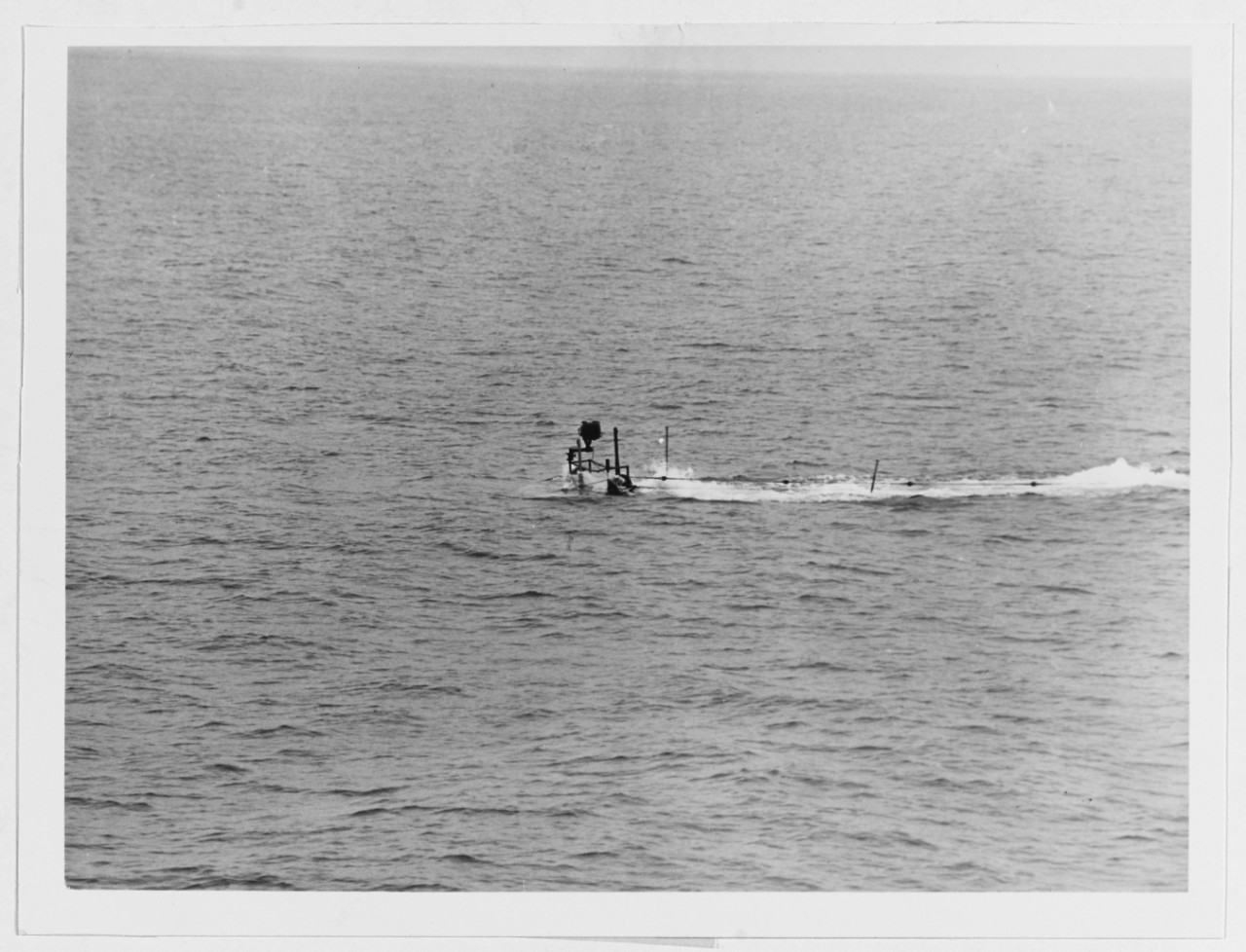

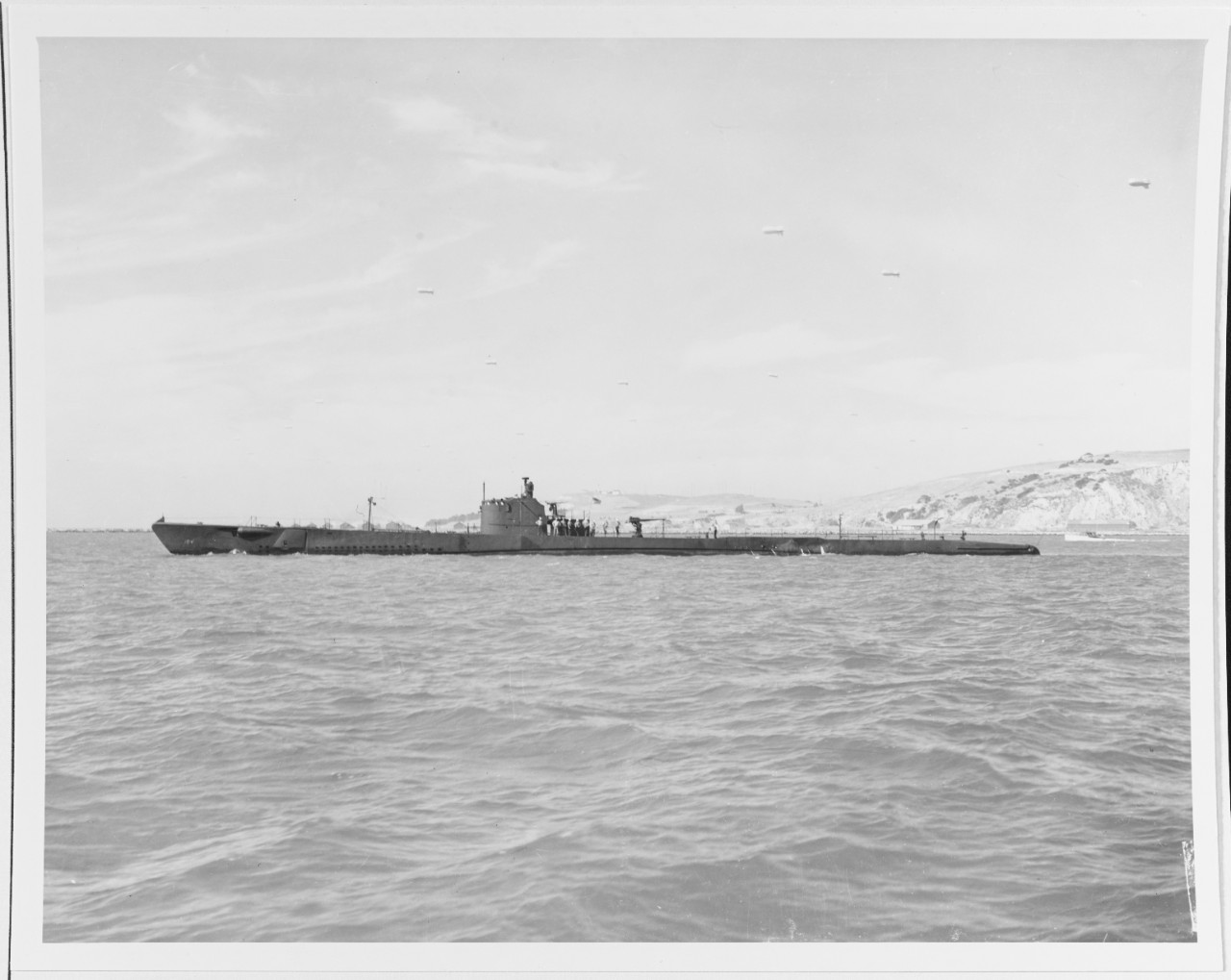

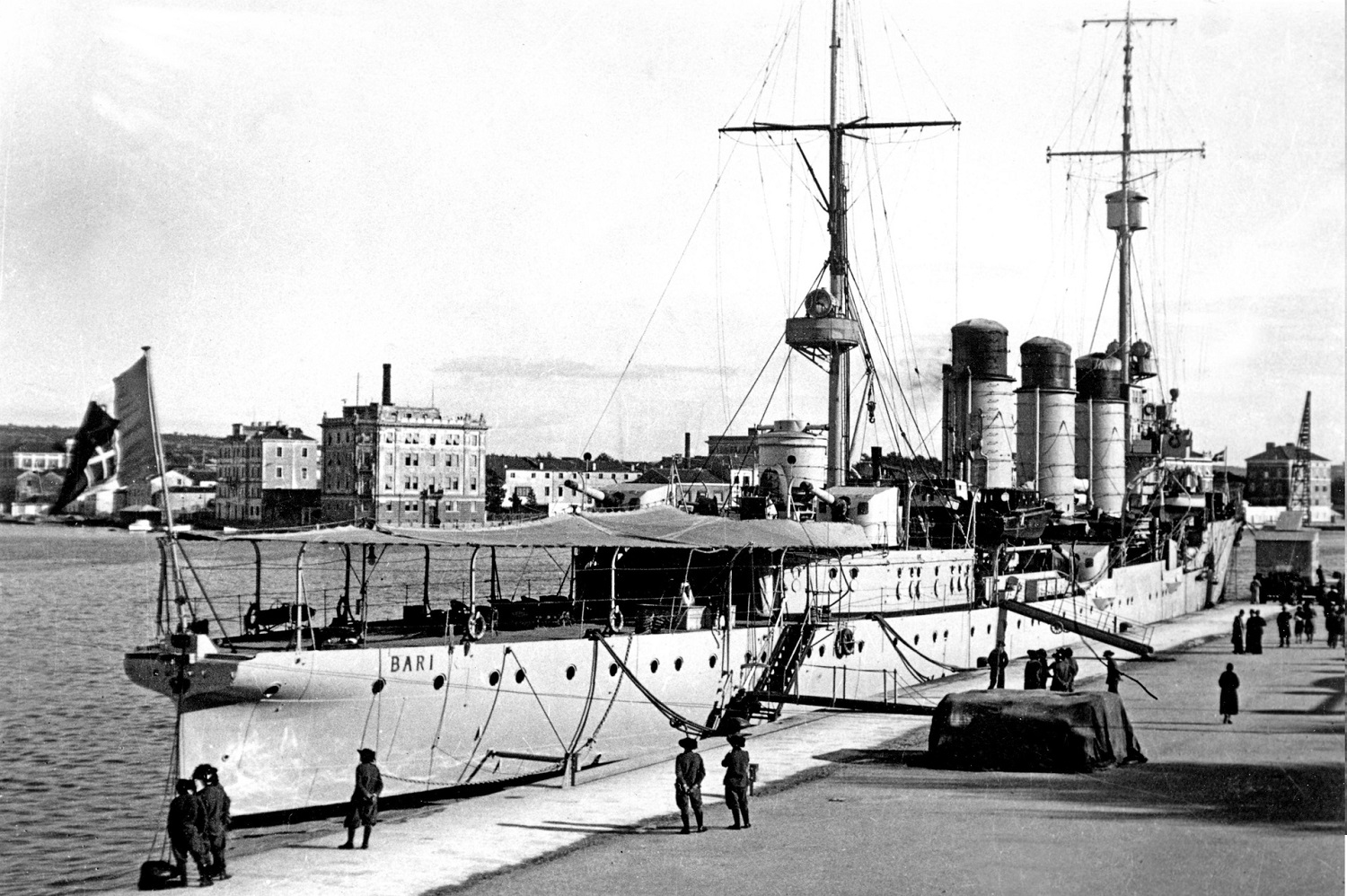

Above we see the Italian light cruiser Bari moored at Patras in Axis-occupied Greece in May 1941. Note her laundry out to dry, her 5.9-inch guns trained to starboard, and her crew assembled on the bow with the band playing. A ship with a strange history, a wandering tale, she was lost some 80 years ago today.

The Muravyov-Amurskiy class

No fleet in military history was in desperate need of a refresh as the Imperial Russian Navy in the 1910s. Having lost 17 battleships (depending on how you classify them), 13 cruisers, 30 Destroyers, and a host of auxiliaries to the Japanese in 1904-1905, the Russians were left with virtually no modern combat ships except those bottled up in the Black Sea by the Ottomans. Also, with lessons learned from the naval clashes, it was clear the way of the future was dreadnoughts, bigger destroyers, and fast cruisers.

To fix this, the Russian Admiralty soon embarked on a plan to build eight very modern 25,000-ton Gangut, Imperatritsa Mariya, and Imperator Nikolai I-class battleships augmented by a quartet of massive 32,000-ton Borodino-class battlecruisers. With the age of the lumbering armored cruiser over, the Russians went with a planned eight-pack of fast new protected cruisers of the Svetlana and Admiral Nakhimov classes (7,000 tons, 30 knots, 15 5.1-inch guns, 2 x torpedo tubes, up to 3 inches of armor) as companions for the new battle wagons.

And, with Russia all but writing off its larger Pacific endeavors, eschewing rebuilding its former battle fleet there in favor of a much more modest “Siberian Military Flotilla” based out of often ice-bound Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk, the Tsar’s admirals deemed that just two light scouting cruisers were needed for overseas use in the Far East, typically to wave the flag, so to speak.

That’s where the Muravyov-Amurskiy class came in.

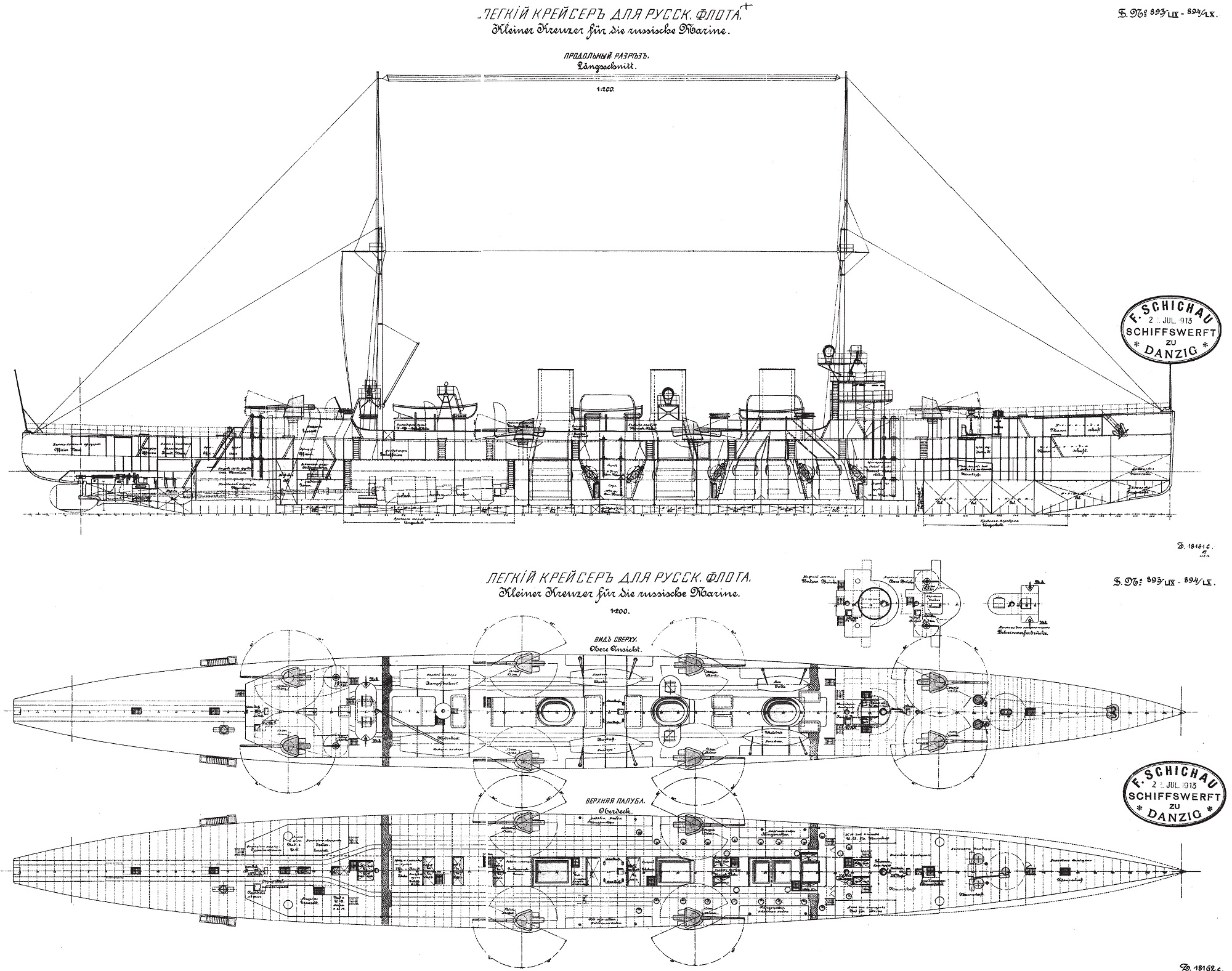

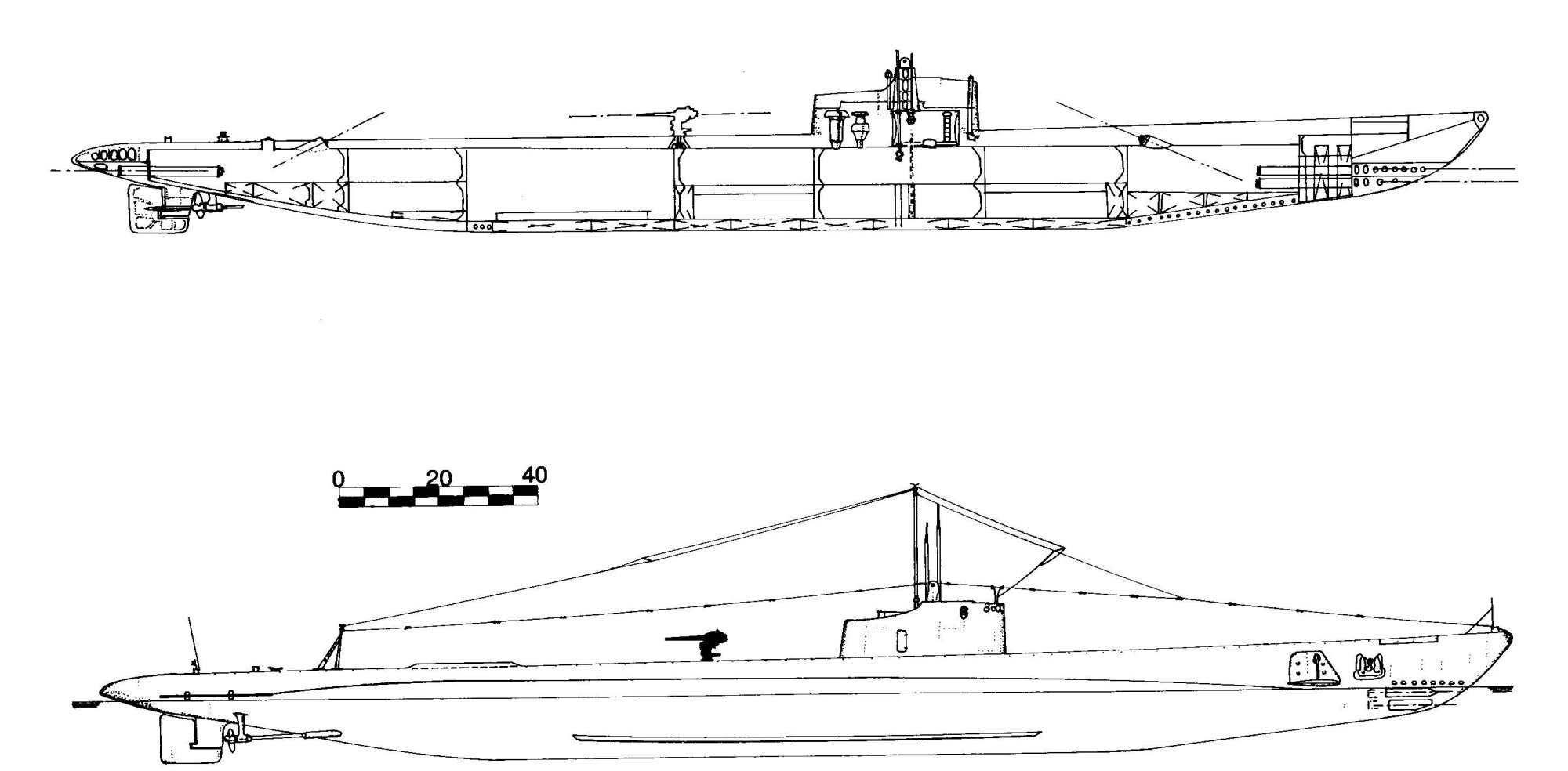

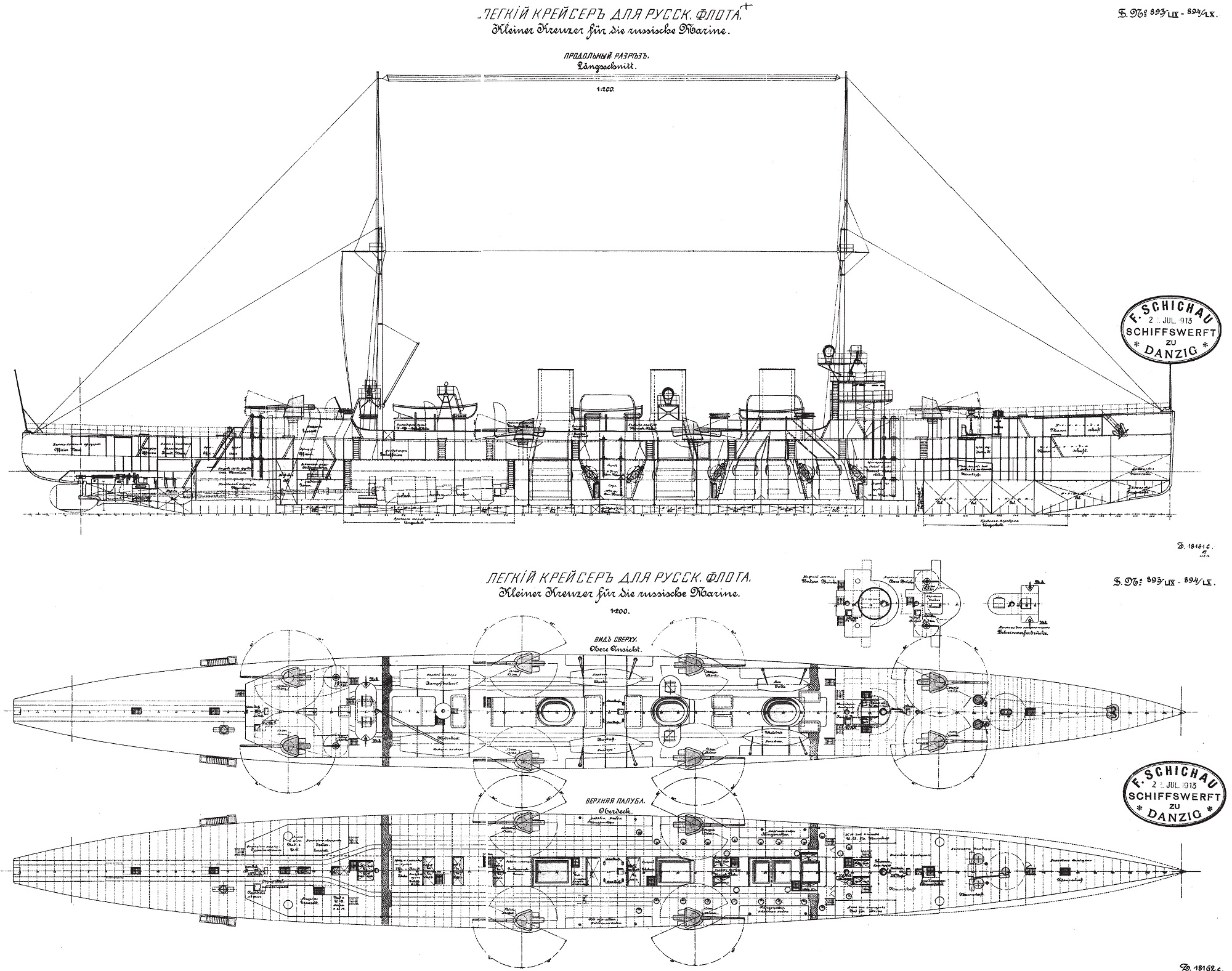

The two cruisers, at 4,500 tons displacement and 426 feet overall length, were generally just reduced versions of the Svetlana/Admiral Nakhimov classes being built in Russian yards already.

Planned to be armed with eight 5.1-inch guns and four torpedo tubes, they were turbine powered and expected to be fast– able to touch 35 knots at standard weight for short periods although published speeds were listed as 27.5 knots.

Mine rails over the stern allowed for up to 120 such devices to be quickly sown– a Russian specialty.

Their armor was thin, never topping three inches, and spotty with just a protective deck above machinery spaces, a protected conning tower, and 50mm gun shields.

Muravyov-Amursky class in 1914 Janes.

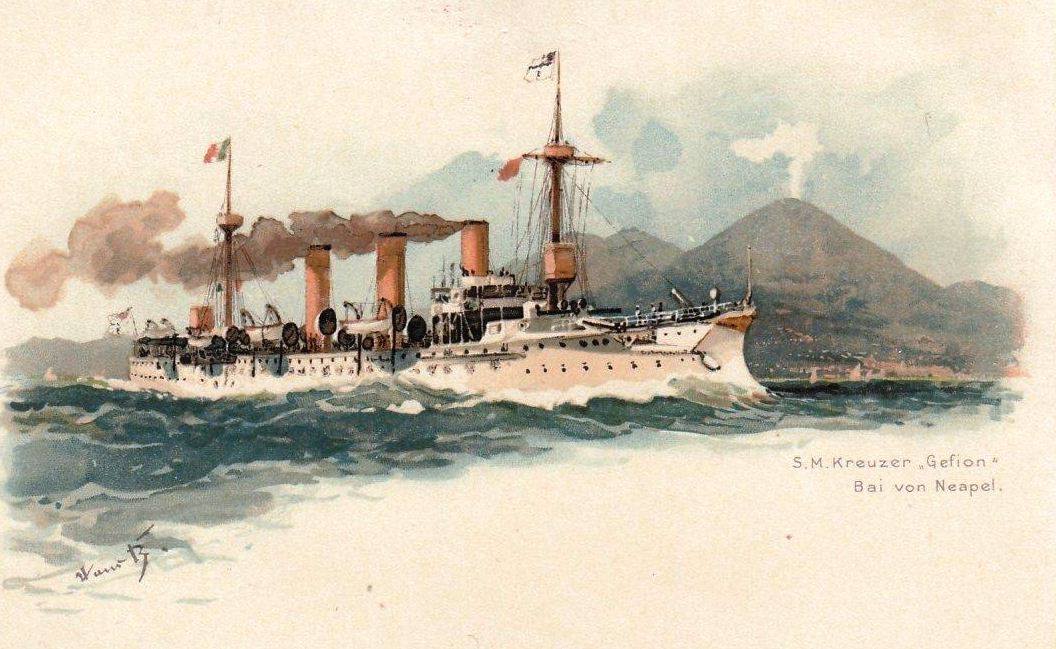

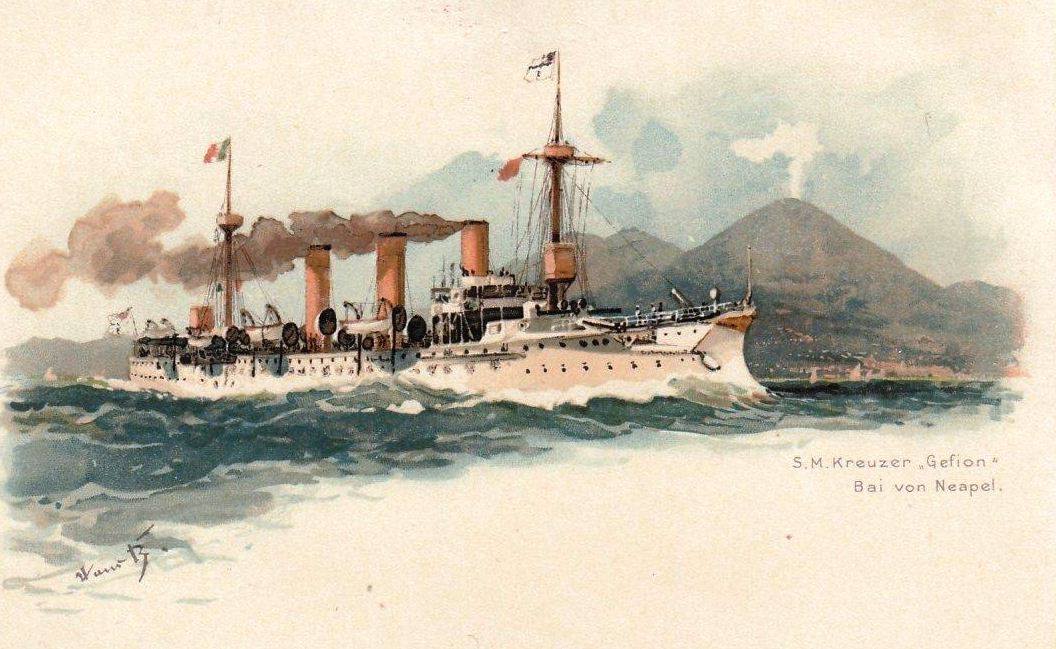

It should be noted the Russian cruisers feel very much like a follow-on to the experimental “cruiser corvette” SMS Gefion (4,275 t, 362 ft oal, 10 x 4-inch guns, 1-inch armor) that Schichau built at Danzig in the mid-1890s for overseas service.

SMS Gefion, commissioned in 1895, would serve briefly in East Asia before she was laid up in 1901. After service as an accommodation hulk through the Great War, she was converted to use as a freighter, Adolf Sommerfeld, in 1920, only to be broken up a few years later.

The two new vessels were to be named after historic 19th Century Russian figures who had expanded the country’s reach towards the Pacific: General Count Nikolay Nikolayevich Muravyov-Amursky, a statesman who proposed abolishing serfdom; and Admiral Gennady Ivanovich Nevelskoy, a noted polar explorer.

General Muravyov-Amursky and Adm. Nevelskoy.

They were ordered in the summer of 1913 from F. Schichau’s Schiffswerft in Danzig, as yard numbers 893 and 894.

The choice to have a German firm build the new cruiser class wasn’t too unusual for the Tsarist fleet as the Russian cruiser Novik and four Kit-class destroyers was built at Schichau in the 1900s while Krupp delivered the early midget submarine Forel at about the same time. The Russian protected cruiser Askold, one of the most successful of her type, was built at Kiel by Germaniawerft while the cruiser Bogatyr was ordered from AG Vulcan’s Stettin shipyards, also in Germany.

Besides German orders and construction at domestic yards along both the Baltic and the Black Sea, the Russians also ordered warships and submarines from France, Britain, Denmark, and the U.S.– they needed the tonnage.

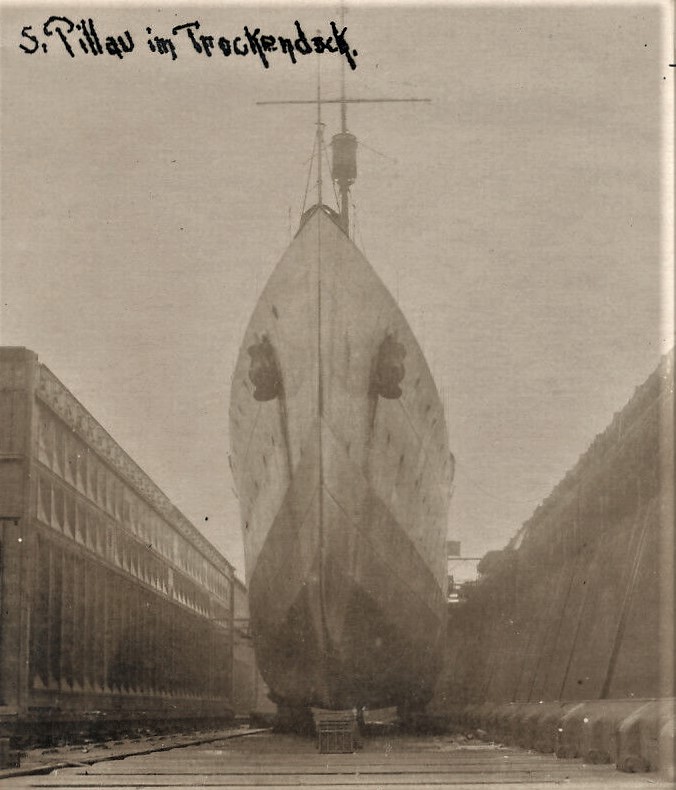

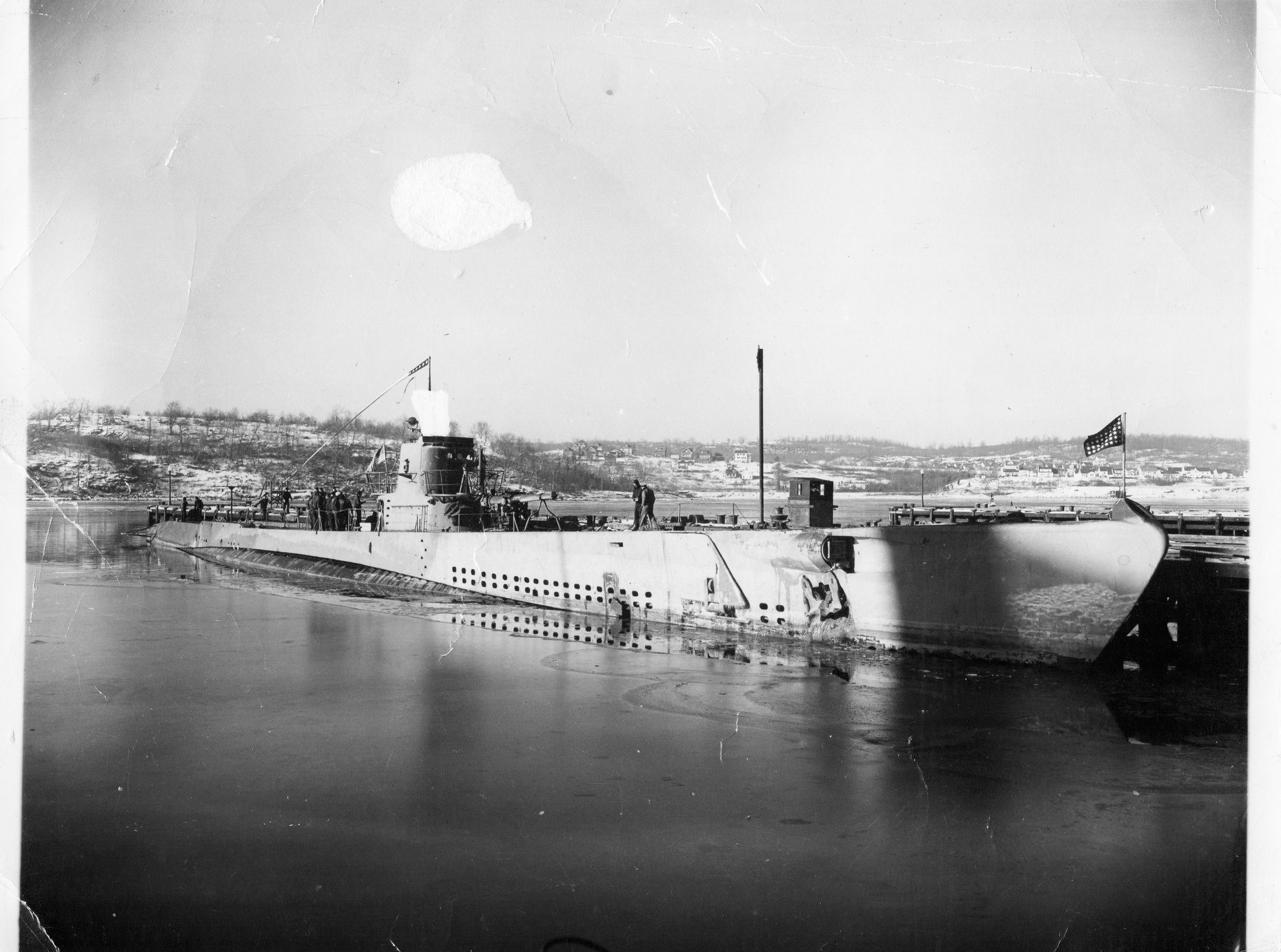

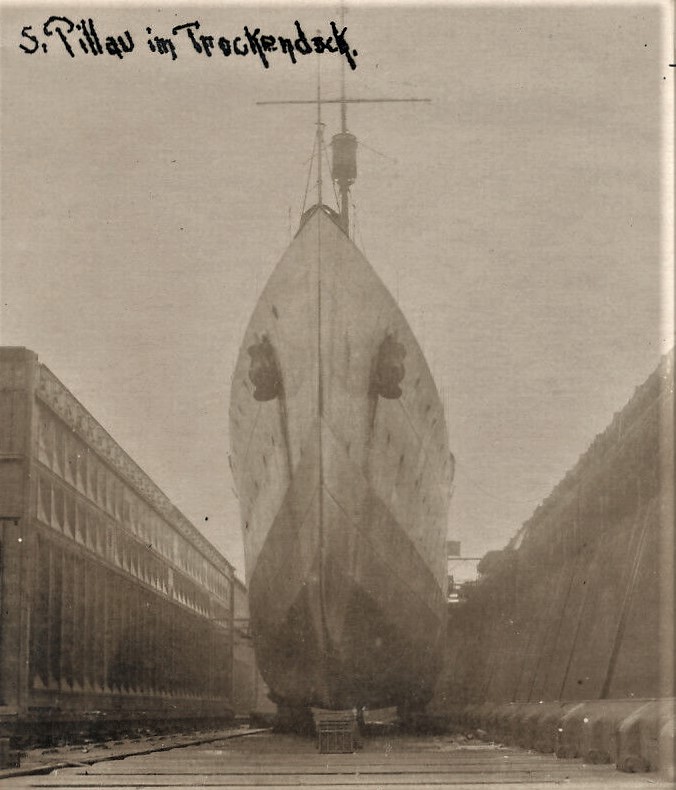

The planned future Muravyov-Amursky at Schichau-Werke, Danzig, on the occasion of her launch, 29 March 1914 (Old Style), 11 April (N.S.).

Ironically, this was at the same period that Russia’s primary military ally was France, whose principal threat was from Germany. However, most Russian Stavka strategists and statesmen of the era assumed that they would be far more likely to fight the Ottomans or Austrians– perhaps even the Swedes– long before the Germans.

Then came August 1914 and relations between Germany and Russia kind of took a turn.

Kreuzer Pillau

When Germany declared war on Imperial Russia, Muravyov-Amursky had been launched just four months prior and was fitting out with an expected delivery in the summer of 1915. Sistership Admiral Nevelskoy was still on the ways with her hull nearly complete. With the Kaiserliche Marine hungry for tonnage, they seized the two unfinished Russian cruisers and rushed them to completion.

Muravyov-Amursky was renamed after the East Prussian town of Pillau, and Nevelskoy after the West Prussian port city of Elbing. Muravyov-Amursky/Pillau was completed in December 1914 and Nevelskoy/Elbing was delivered the following September.

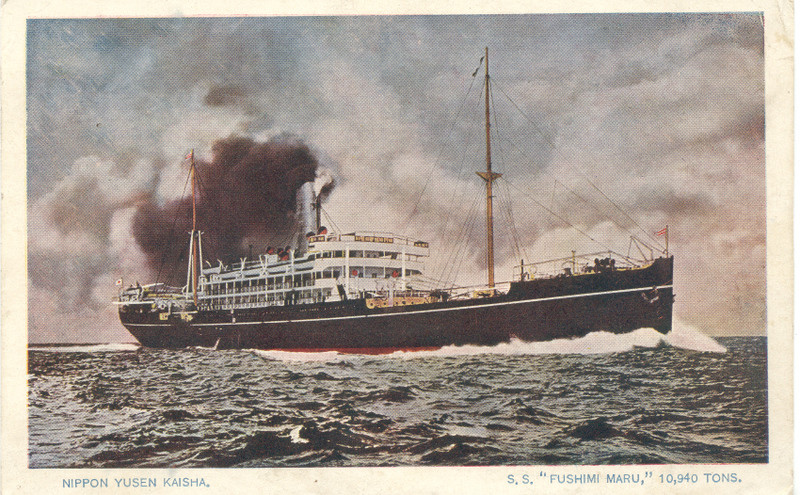

To keep them more in line with the rest of the German battleline, they were fitted with slightly larger (and better) 15 cm/45 (5.9″) SK L/45 guns, the same type used as secondary armament on German battleships and battlecruisers as well as later on most of their cruisers built during the Great War.

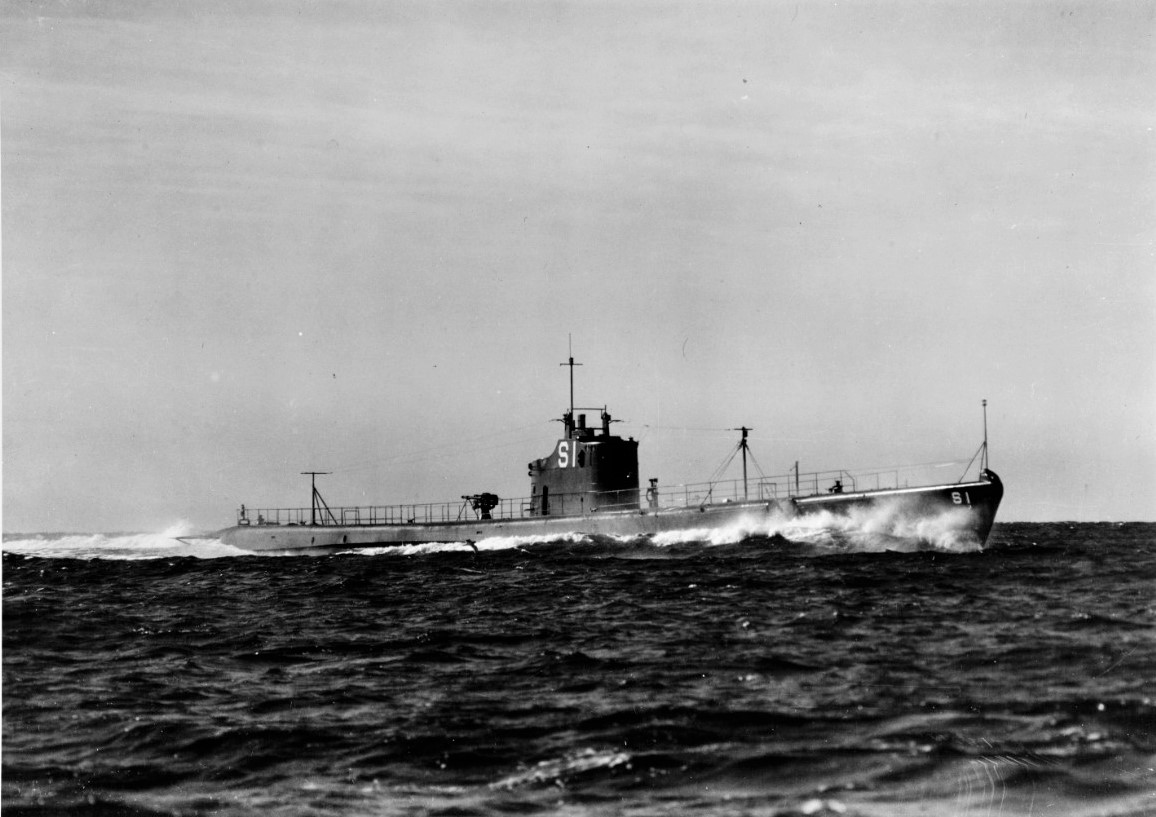

Pillau as seen during her German career. Courtesy of Master Sergeant Donald L.R. Shake, USAF, 1981. NHHC Catalog #: NH 92715

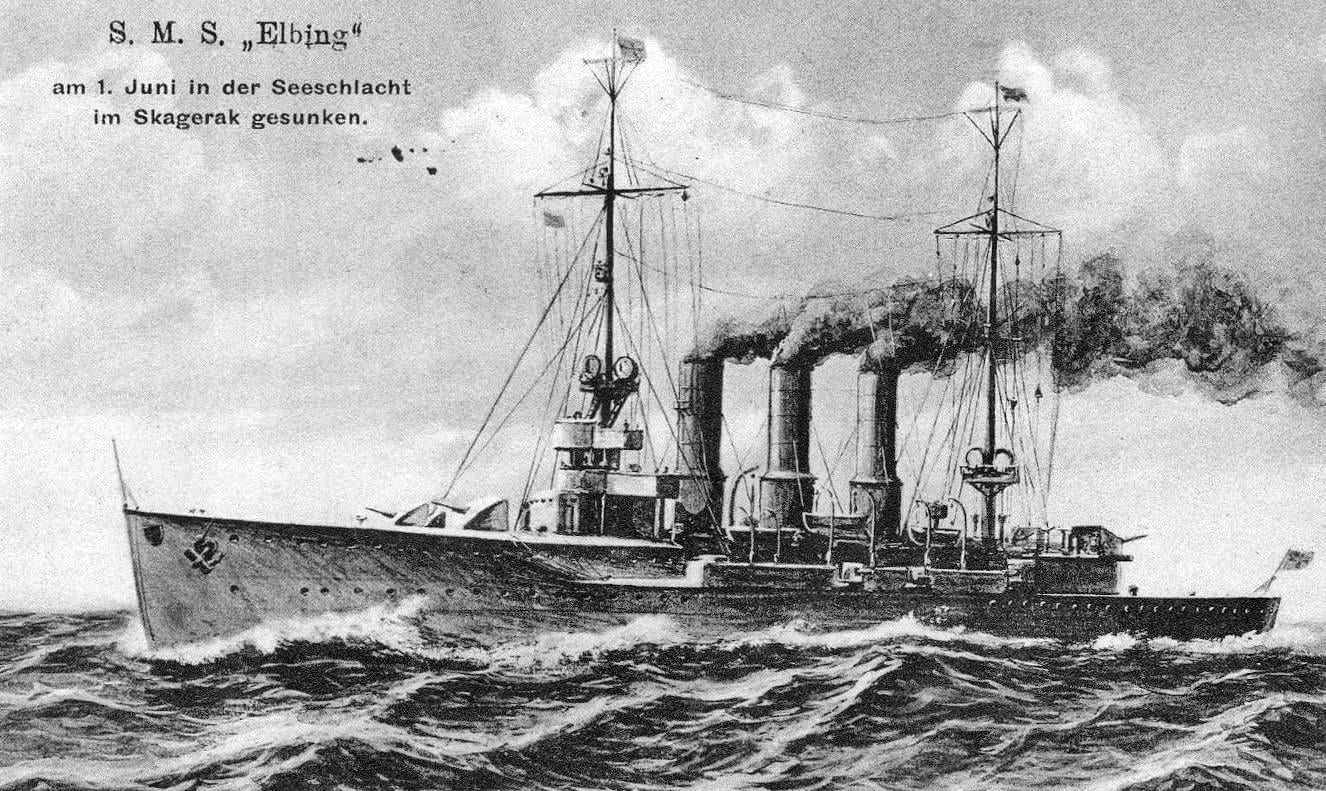

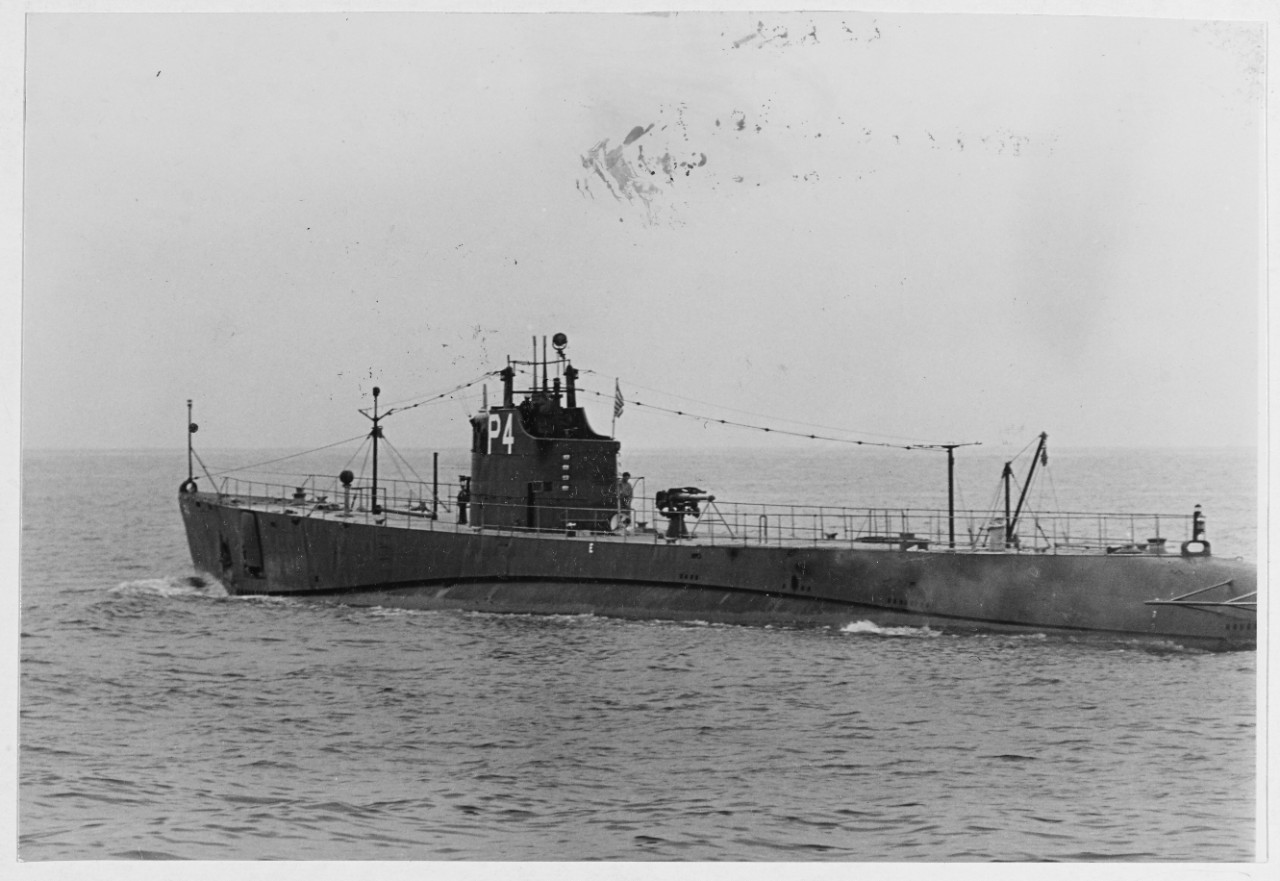

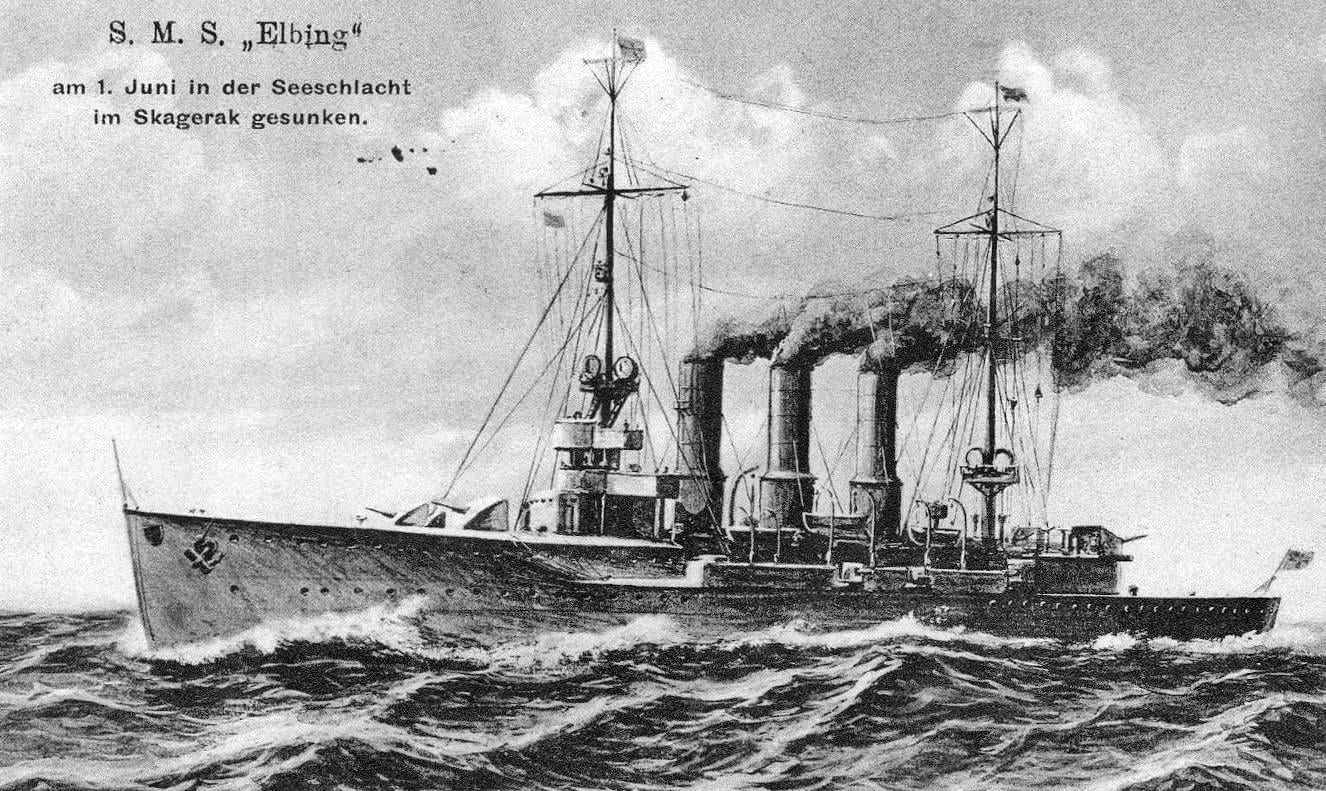

SMS Elbing of the Pillau class, circa 1915-16

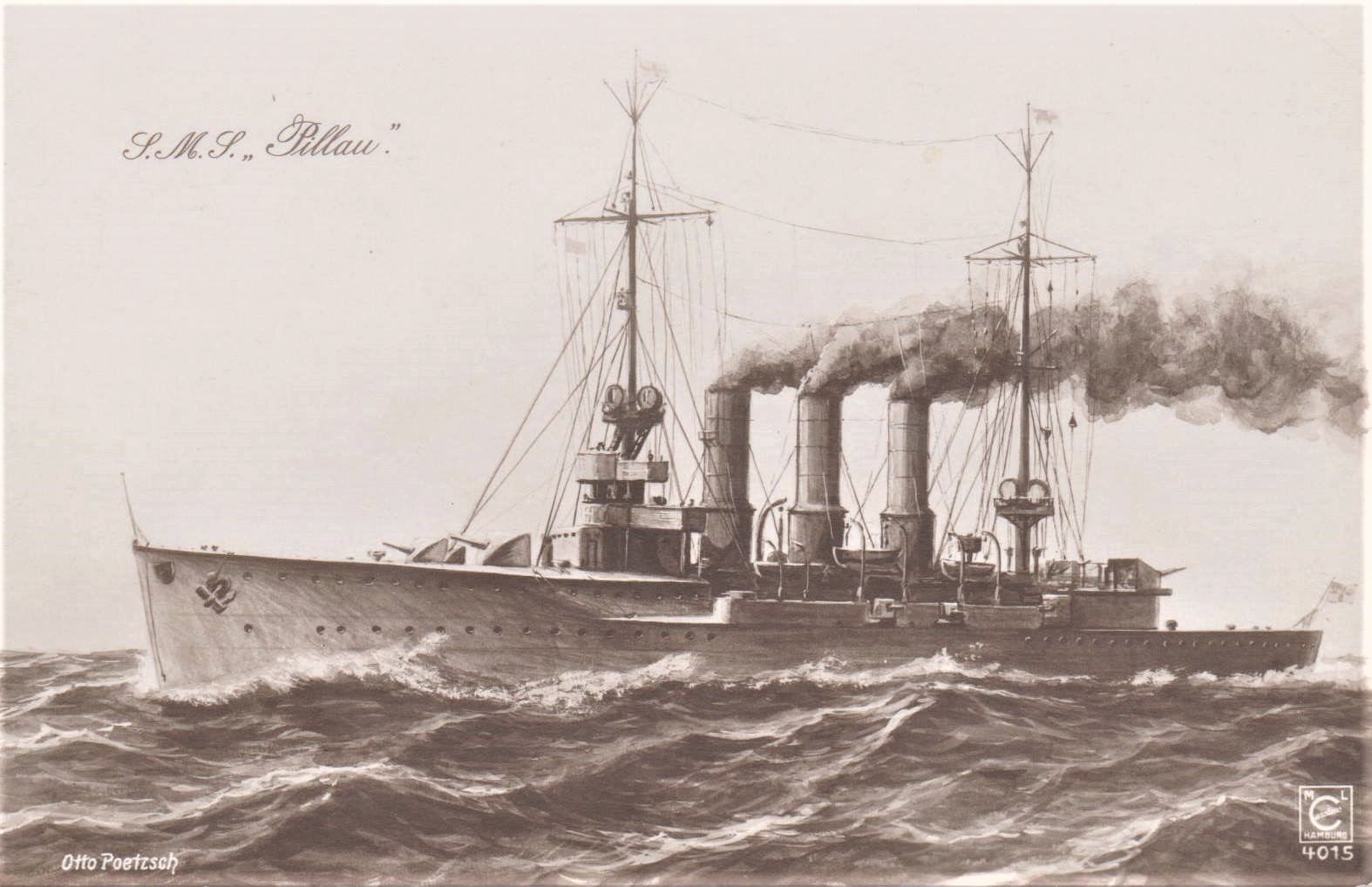

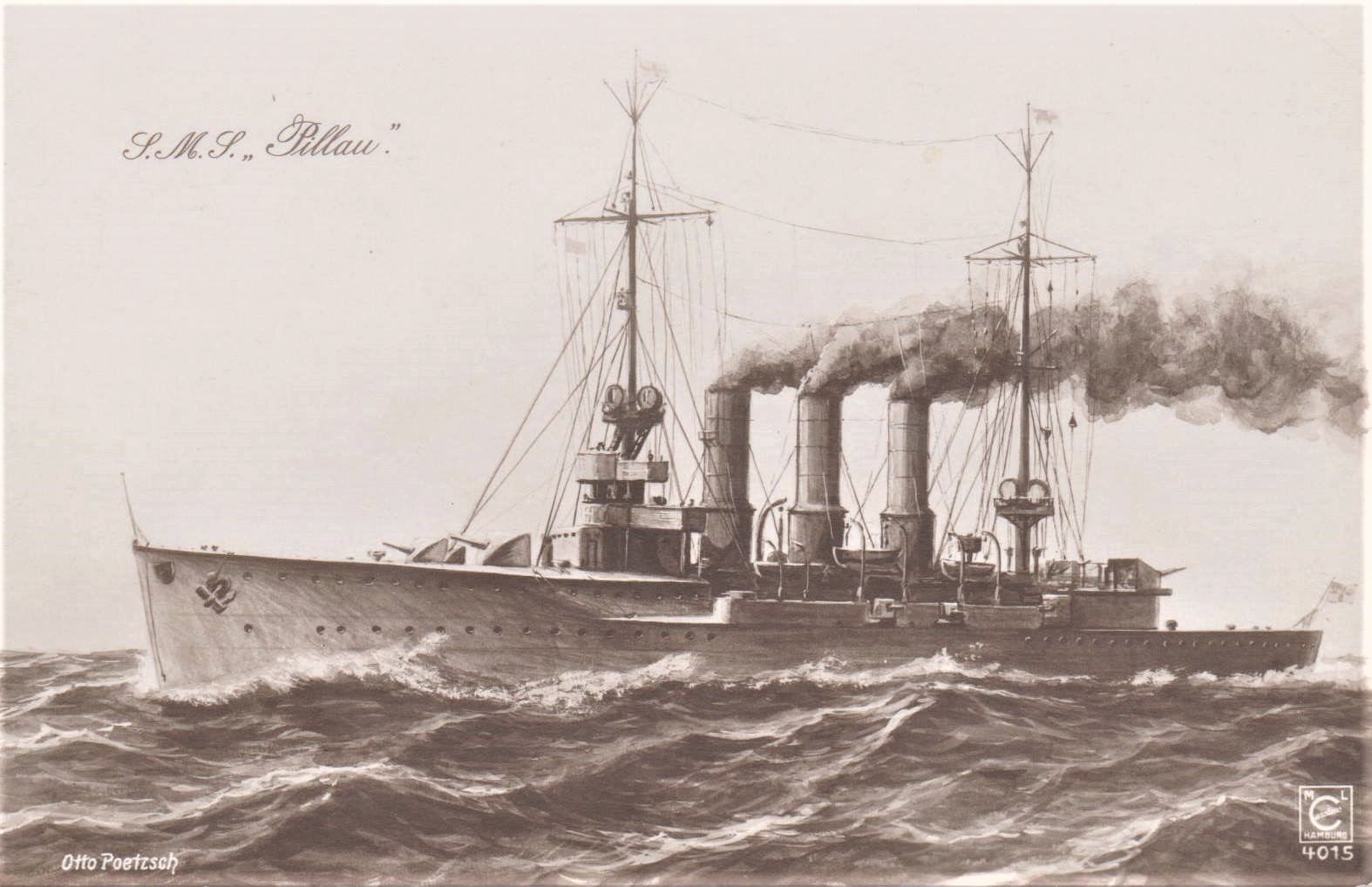

SMS Pillau shortly after entering service, 1915

Pillau had her baptism of fire in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915– ironically against the Russians– while Elbing took part in the bombardment of Yarmouth in April 1916. Both were assigned to the High Seas Fleet’s 2nd Scouting Group (II. Aufklärungsgruppe), commanded by Contre-Admiral Bödicker, and took a key role in the Battle of Jutland.

While Jutland is such a huge undertaking that I won’t even attempt to showcase it all in this post as I would never have the scope to do it properly, Elbing scored the first hit in the battle, landing a 5.9-inch shell against HMS Galatea from an impressive distance of about 13.000 m at 14.35 on 31 May. In the subsequent night action, she was accidentally rammed by the German dreadnought SMS Posen and had to be abandoned, with some of her crew saved by the destroyer S 53 and others landed on the Danish coast by a passing Dutch trawler.

As for Pillau, she was hit by a single large-caliber shell– a 12-incher from the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible— that left her damaged but still in the fight while she is credited with landing hits of her own on the cruiser HMS Chester. In all, Pillau had fired no less than 113 5.9-inch shells and launched a torpedo in the epic sea clash while suffering just four men killed and 23 wounded from her hit from Inflexible.

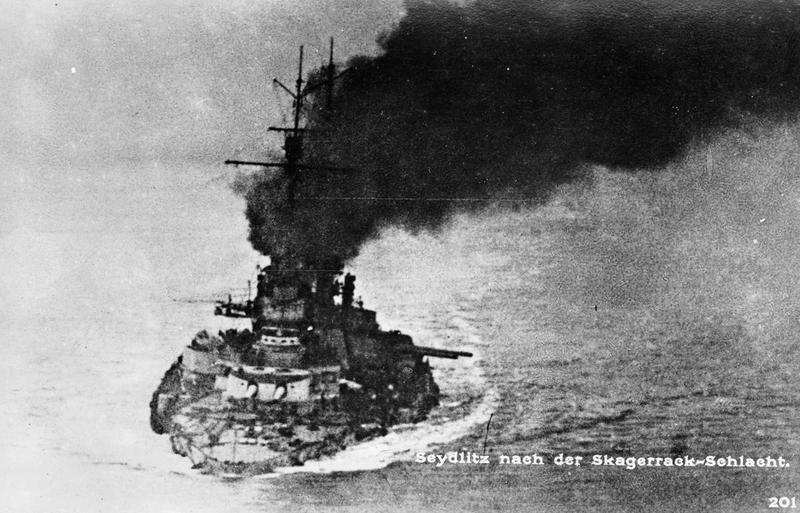

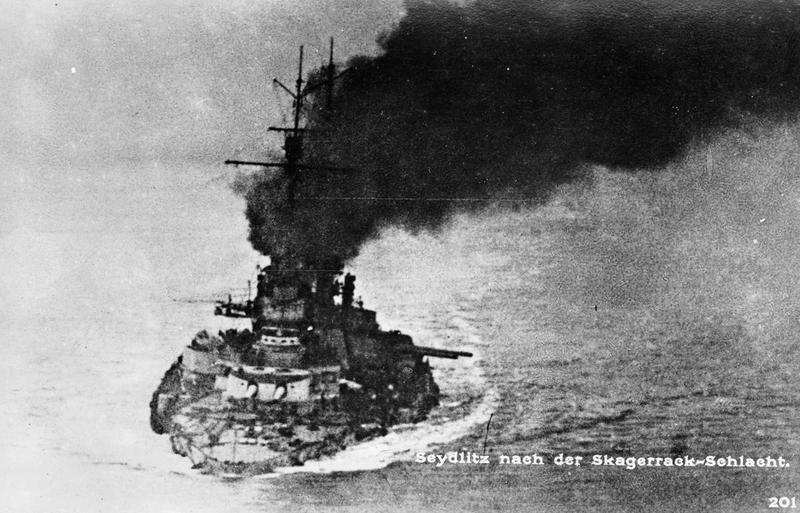

Her chart house blown to memories and half of her boilers out of action but still afloat, Pillau then served as the seeing eye dog for the severely damaged battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz— hit 21 times by heavy-caliber shells, twice by secondary battery shells, and once by a torpedo– on a slow limp back to Wilhelmshaven with the dreadnought’s bow nearly completely submerged.

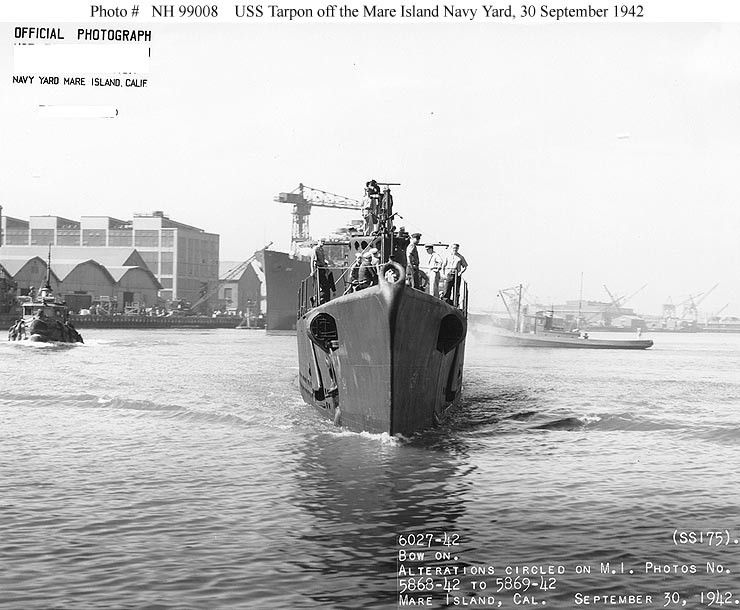

German battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz, low in the water after Jutland. The image was likely taken from Pillau, who led her back to Wilhelmshaven from the battle

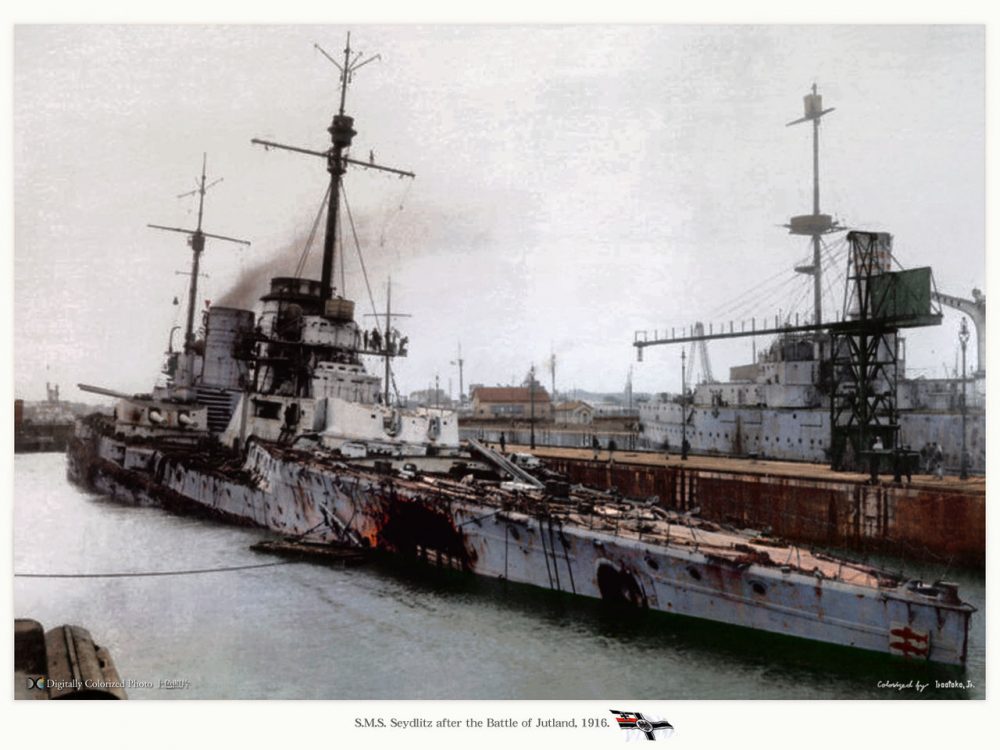

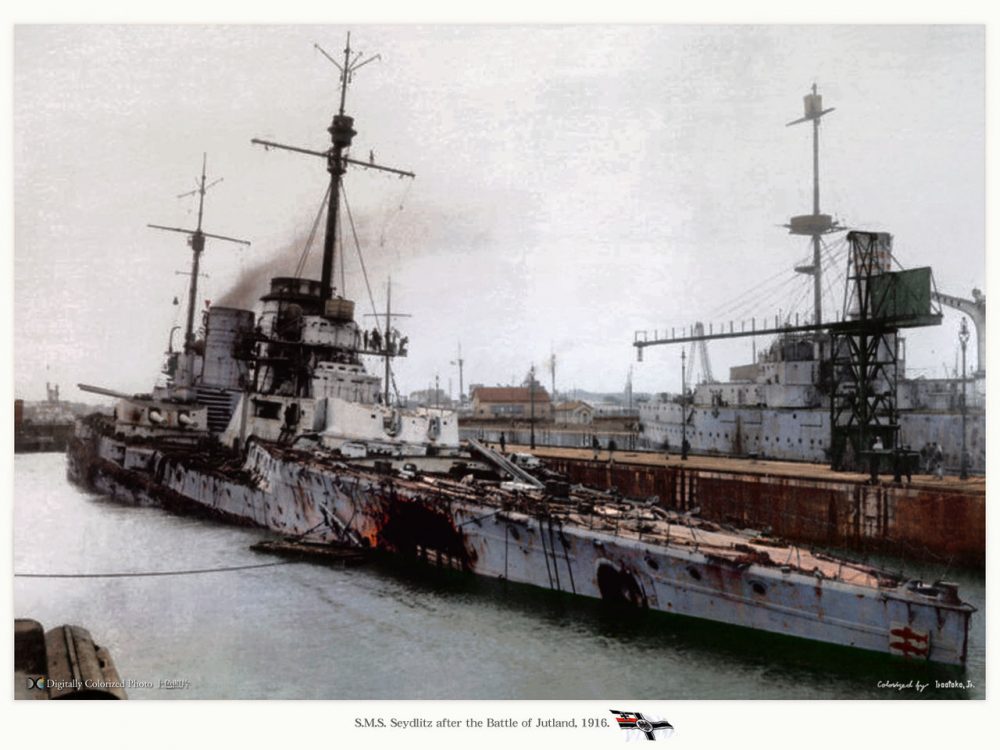

SMS Seydlitz after the Battle of Jutland, 1916. Amazingly, she only suffered 150 casualties during all that damage and would return to service by November– just six months later. Colorized photo by Atsushi Yamashita/Monochrome Specter http://blog.livedoor.jp/irootoko_jr/

Then, her work done, Pillau had to lick her wounds.

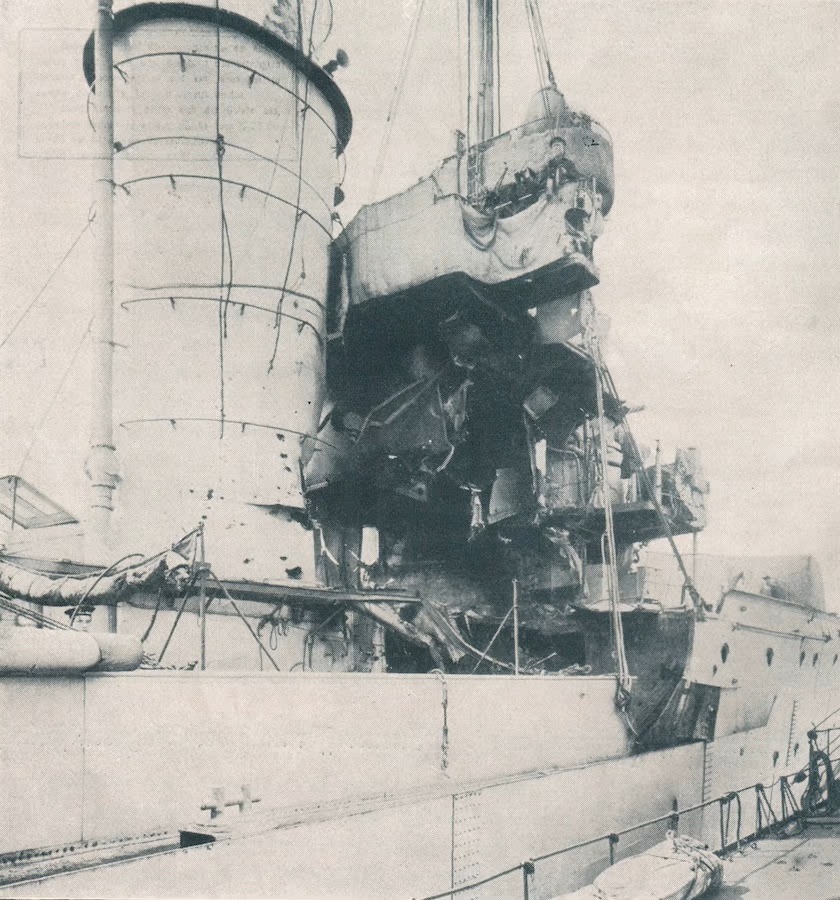

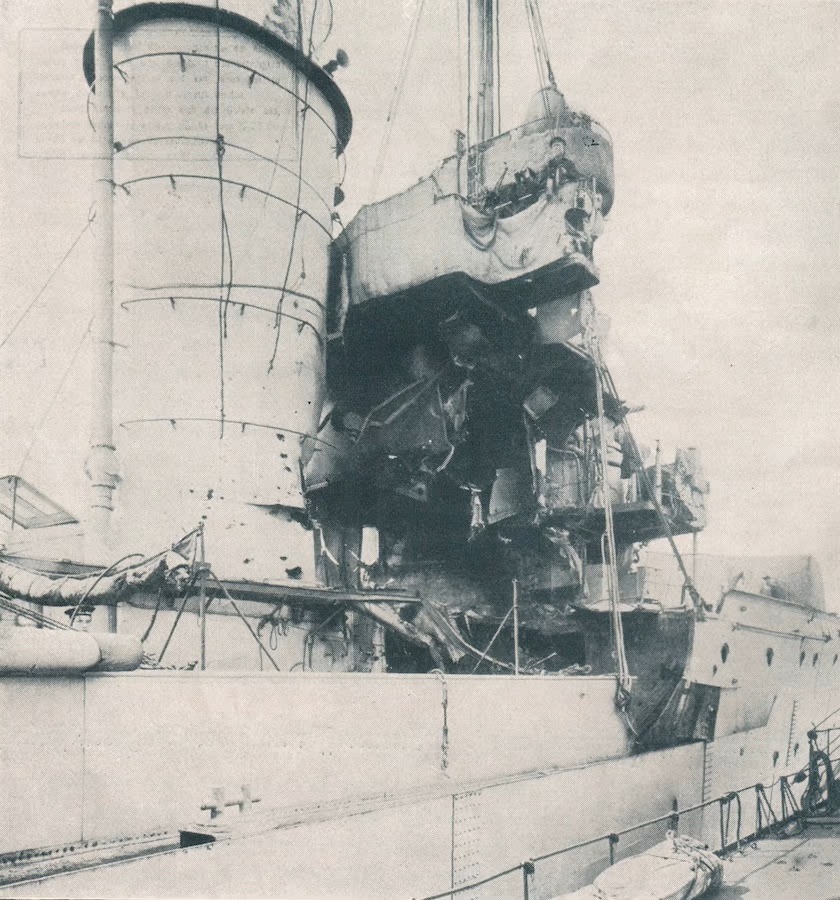

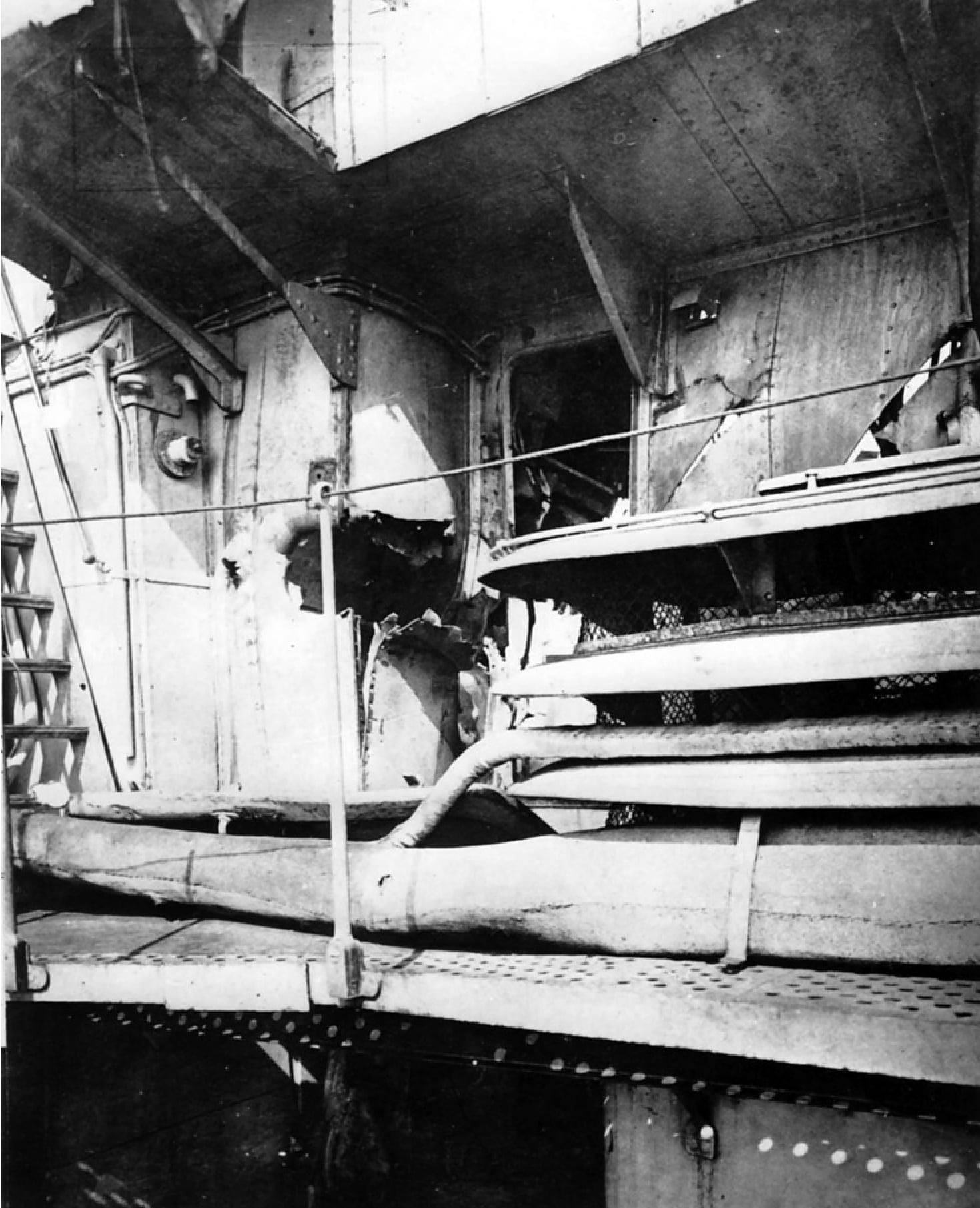

SMS Pillau in Wilhelmshaven showing heavy damage to her bridge, caused by a 12-in shell hit from the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible.

She only suffered 27 casualties at Jutland while her sister, Elbing, was lost.

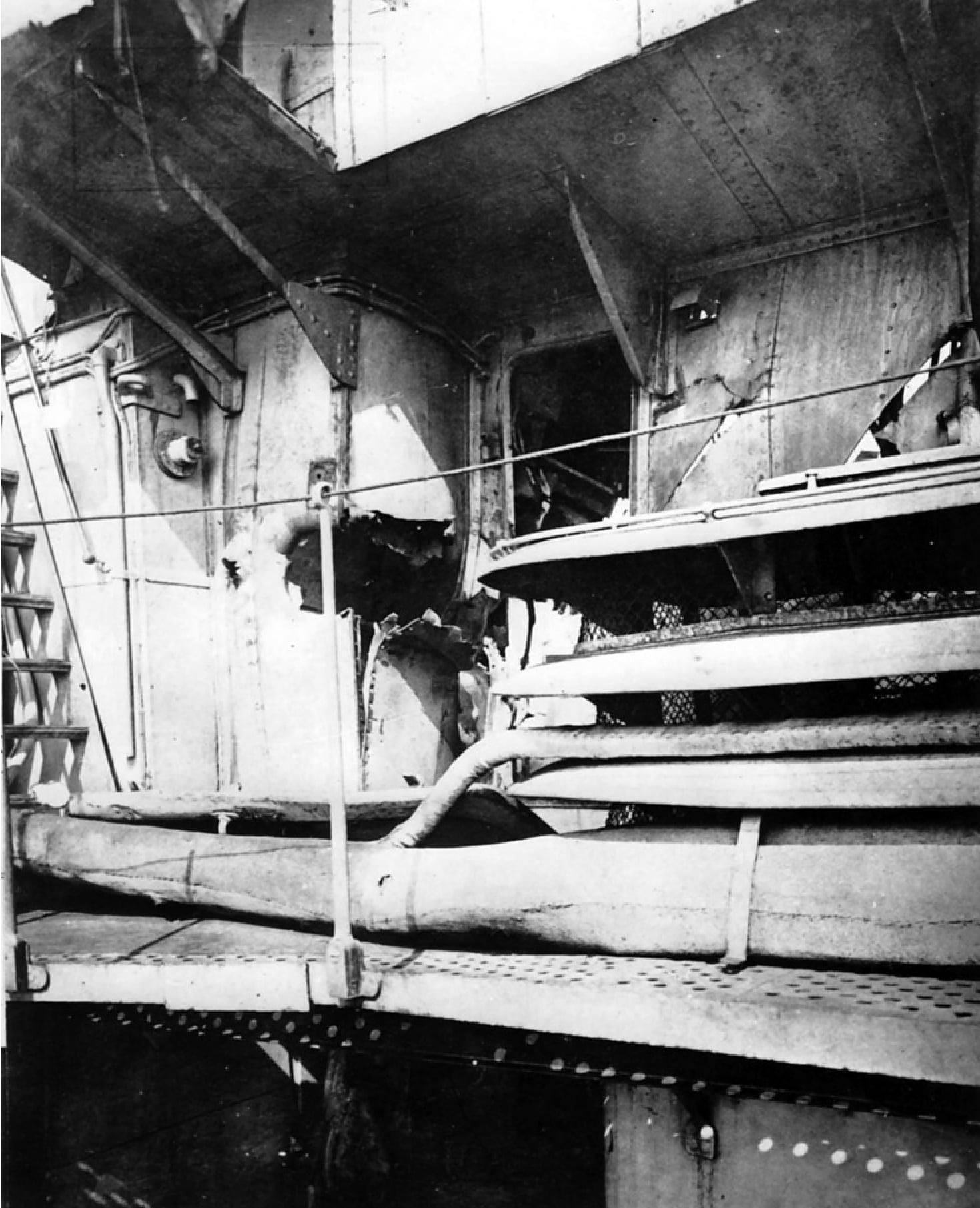

The entry wound, so to speak

Repaired, Pillau took part in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight on 17 November 1917 as well as other more minor operations before the end game in October 1918 in which her crewed mutinied and raised the red flag rather than head out in a last “ride of the Valkyries” suicide attack on the British Home Seas Fleet.

SMS Pillau passing astern of a ship of the line, winter 1917

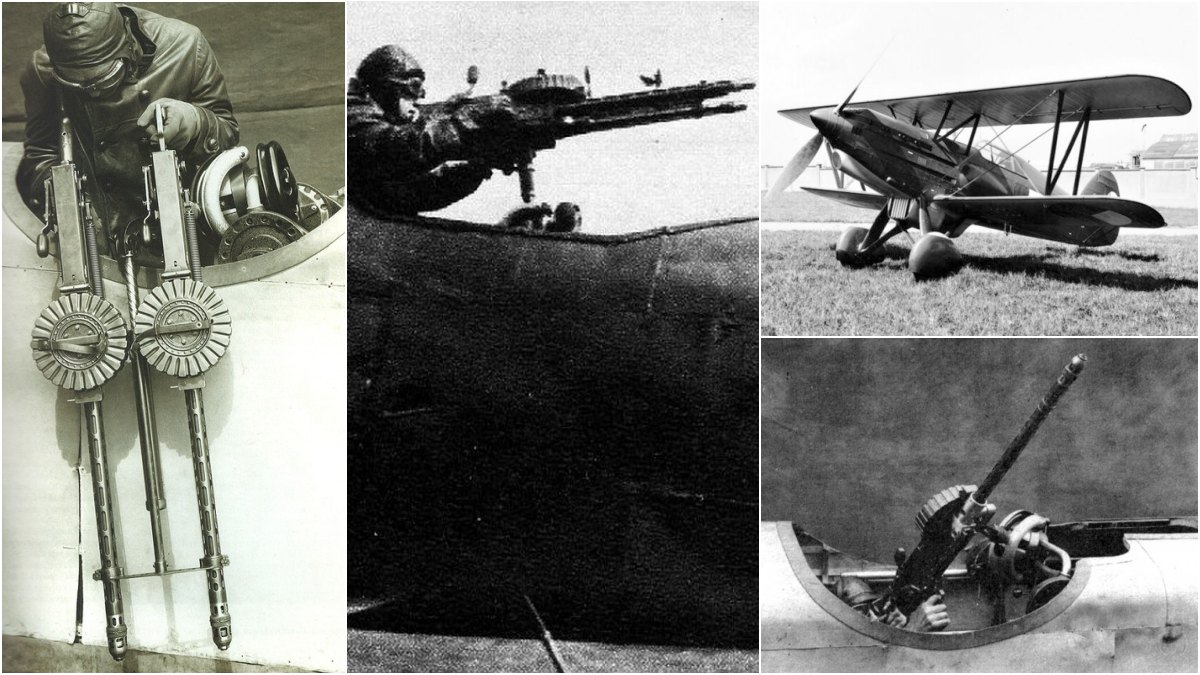

SMS Pillau on patrol in Helgoland Bay, 1918 note AAA gun forward

Incrociatore Bari

Retained at Wilhelmshaven as part of the rump Provisional Realm Navy (Vorläufige Reichsmarine) under the aged VADM Adolf von Trotha while 74 ships of the High Seas Fleet surrendered to the British in November 1918 to comply with the Armistice, Pillau was saved from the later grand scuttling of that interned force seven months later at Scapa Flow.

The victorious allies, robbed of the choicest cuts of the German fleet, in turn, demanded Pillau be turned over for reparations along with a further nine surviving battleships, 15 cruisers, 59 destroyers, and 50 torpedo boats. Pillau was therefore steamed to Cherbourg and decommissioned by the Germans in June 1920.

It was decided that Pillau was to go to the Italians as a war prize, with the Regia Marina renaming her after the Adriatic port city of Bari in Italy’s Puglia region. The Italians also were to receive the surrendered German light cruisers SMS Graudenz and SMS Stassburg, the destroyer flotilla leader V.116, and the destroyers B.97 and S.63. Italy would further inherit a host of former Austrian vessels including the battleships Tegtthof, Zrinyi, and Radetzky; the cruisers Helgoland and Saida; and 15 destroyers.

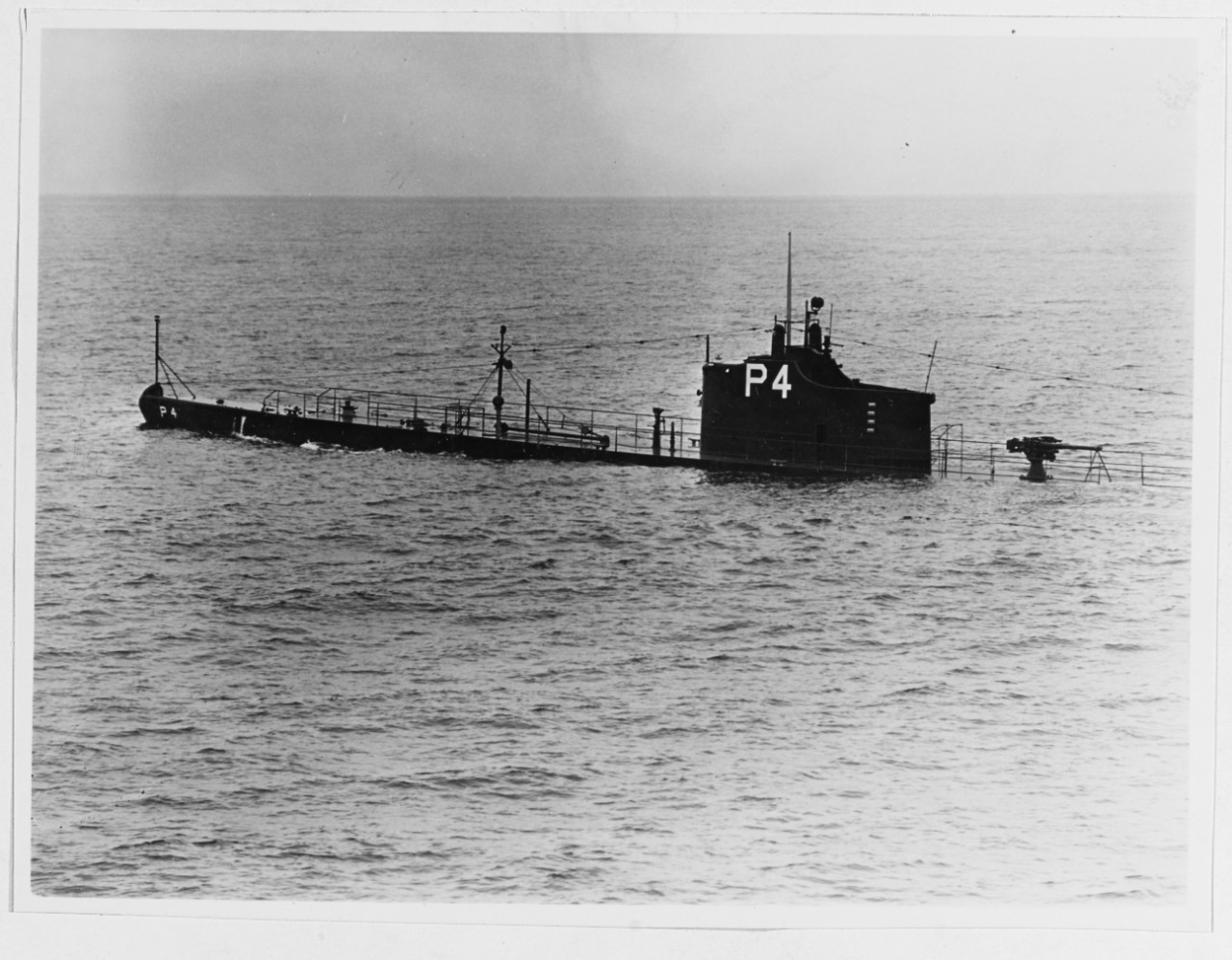

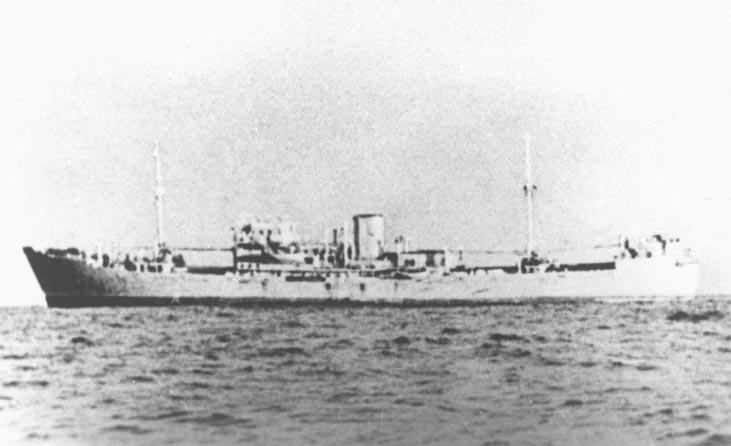

The future light cruiser Bari seen in rough shape, with the provisional denomination “U” painted on her bow, right after being ceded to Italy, Taranto, 5 May 1921.

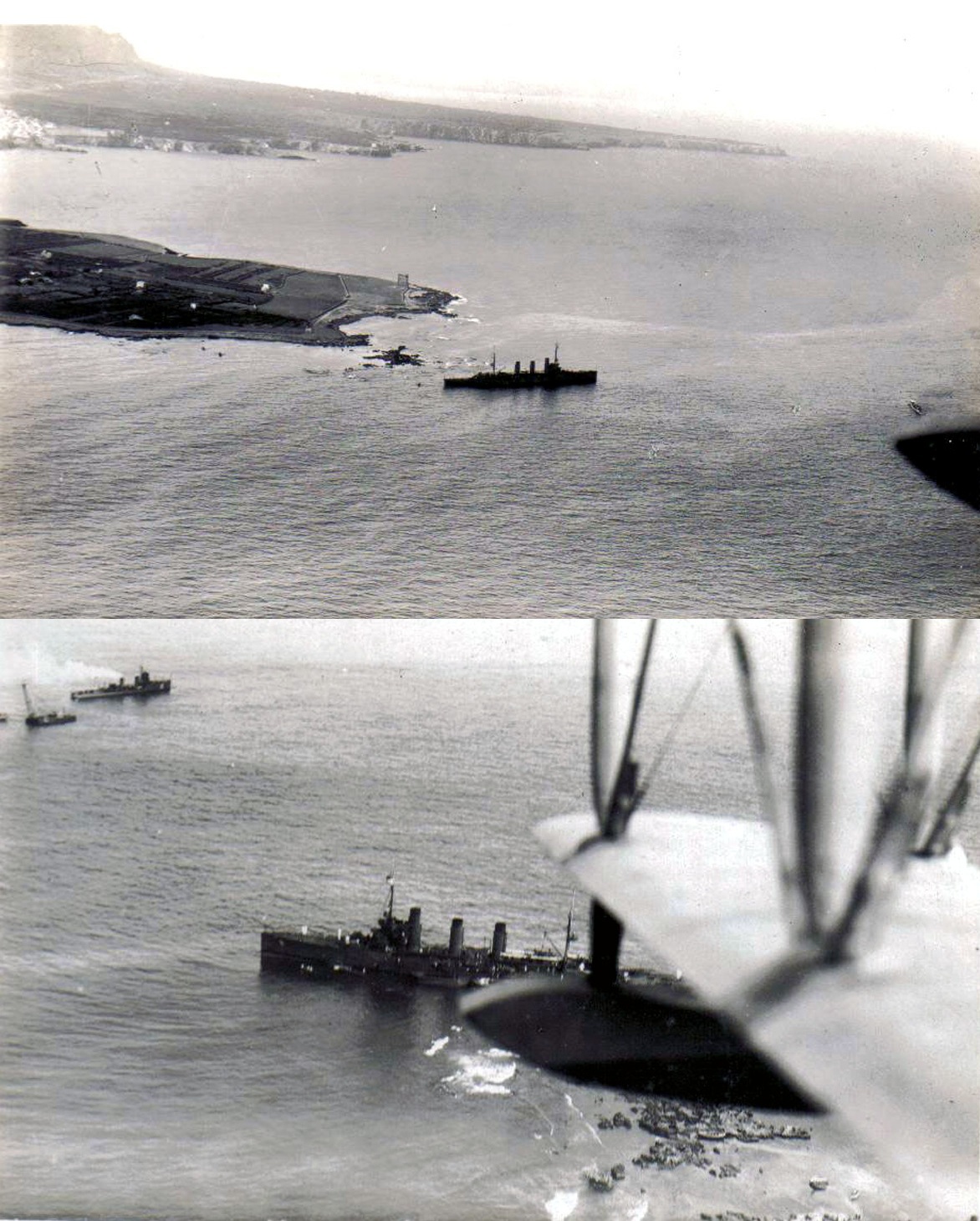

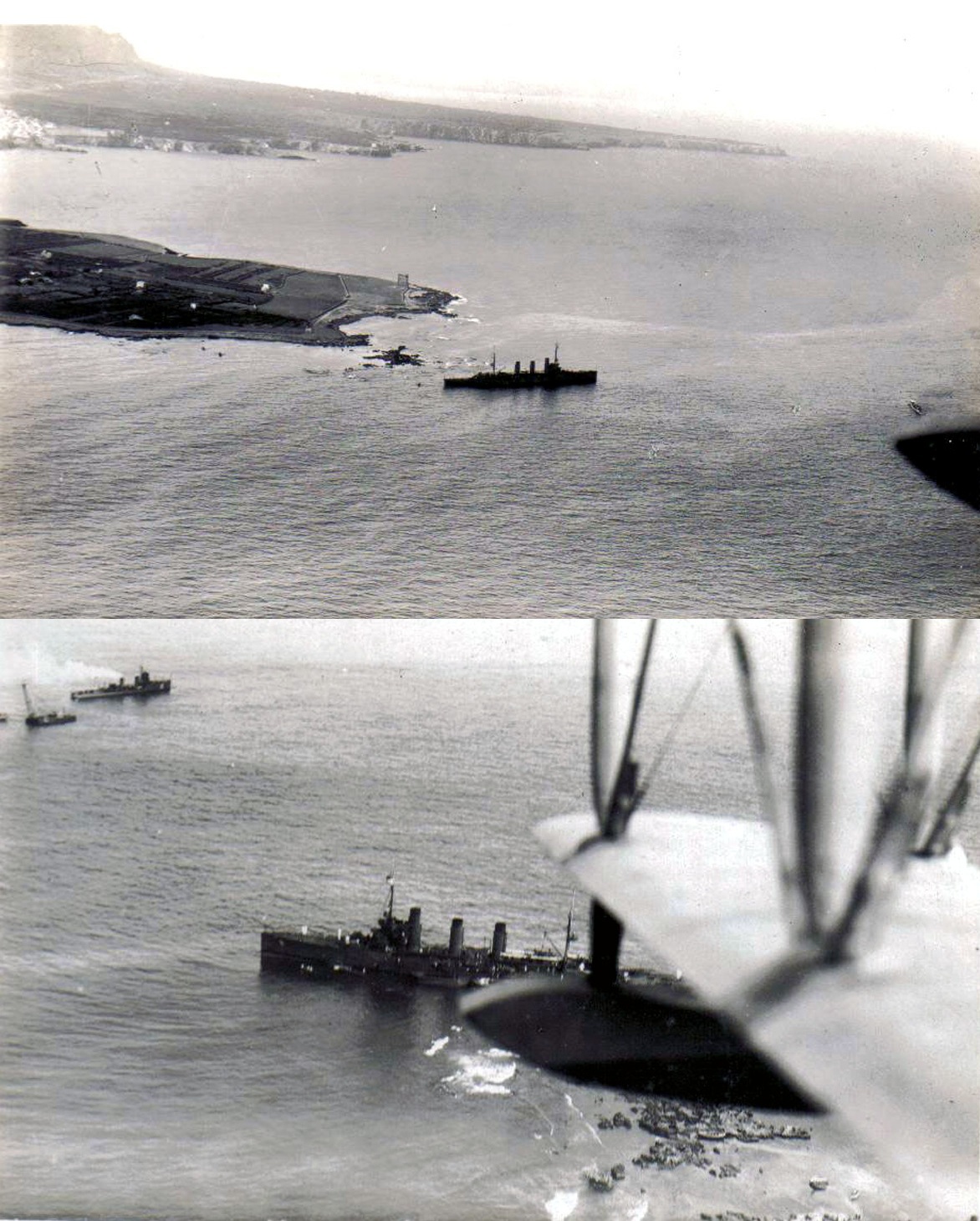

Embarrassingly, just after she entered service with the Italians, Bari ran aground at Terrasini and was stuck there for a week before being refloated.

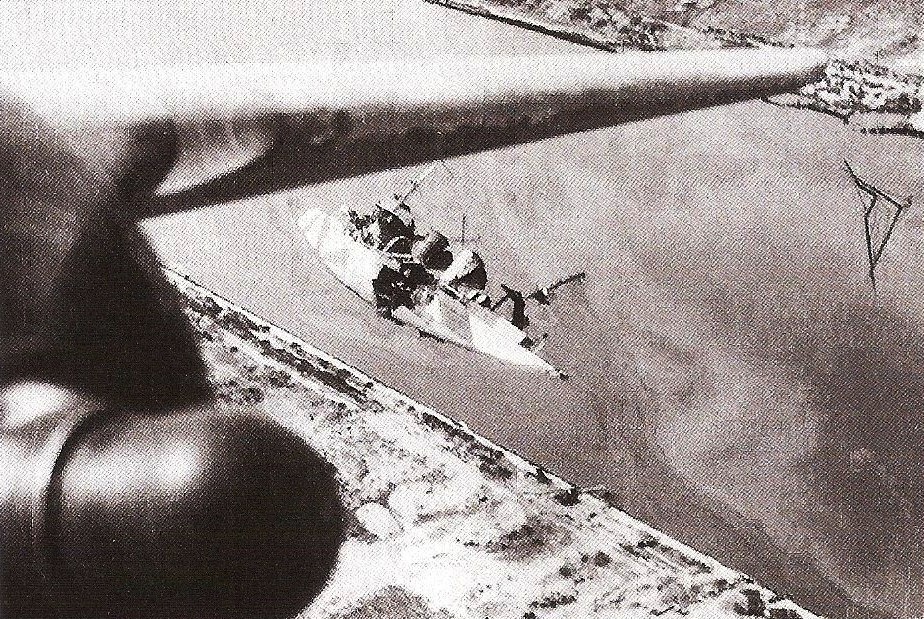

Aerial photos of Bari stranded at Terrasini, 28 August 1925.

Still, she went on to have a useful and somewhat happy peacetime service with the Italian fleet.

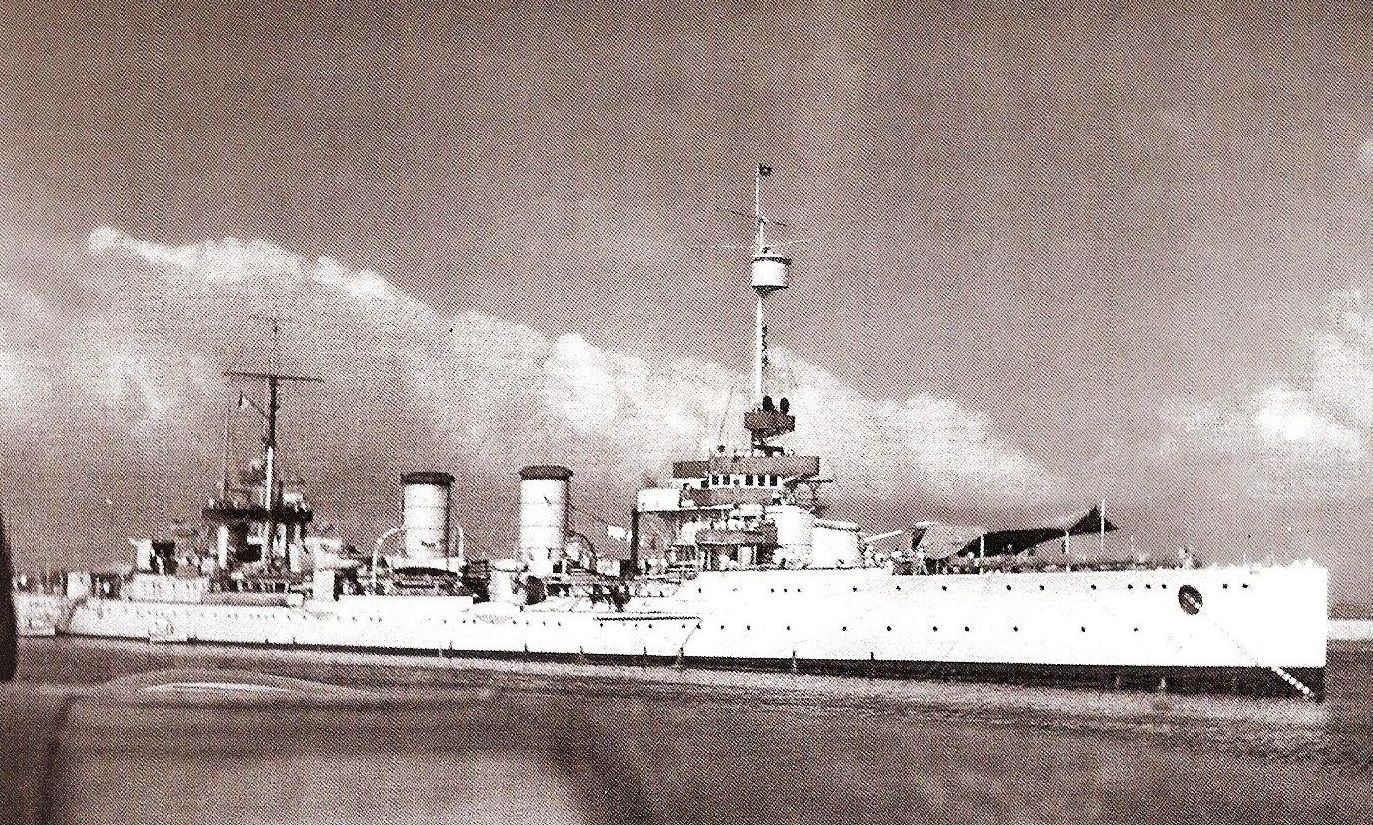

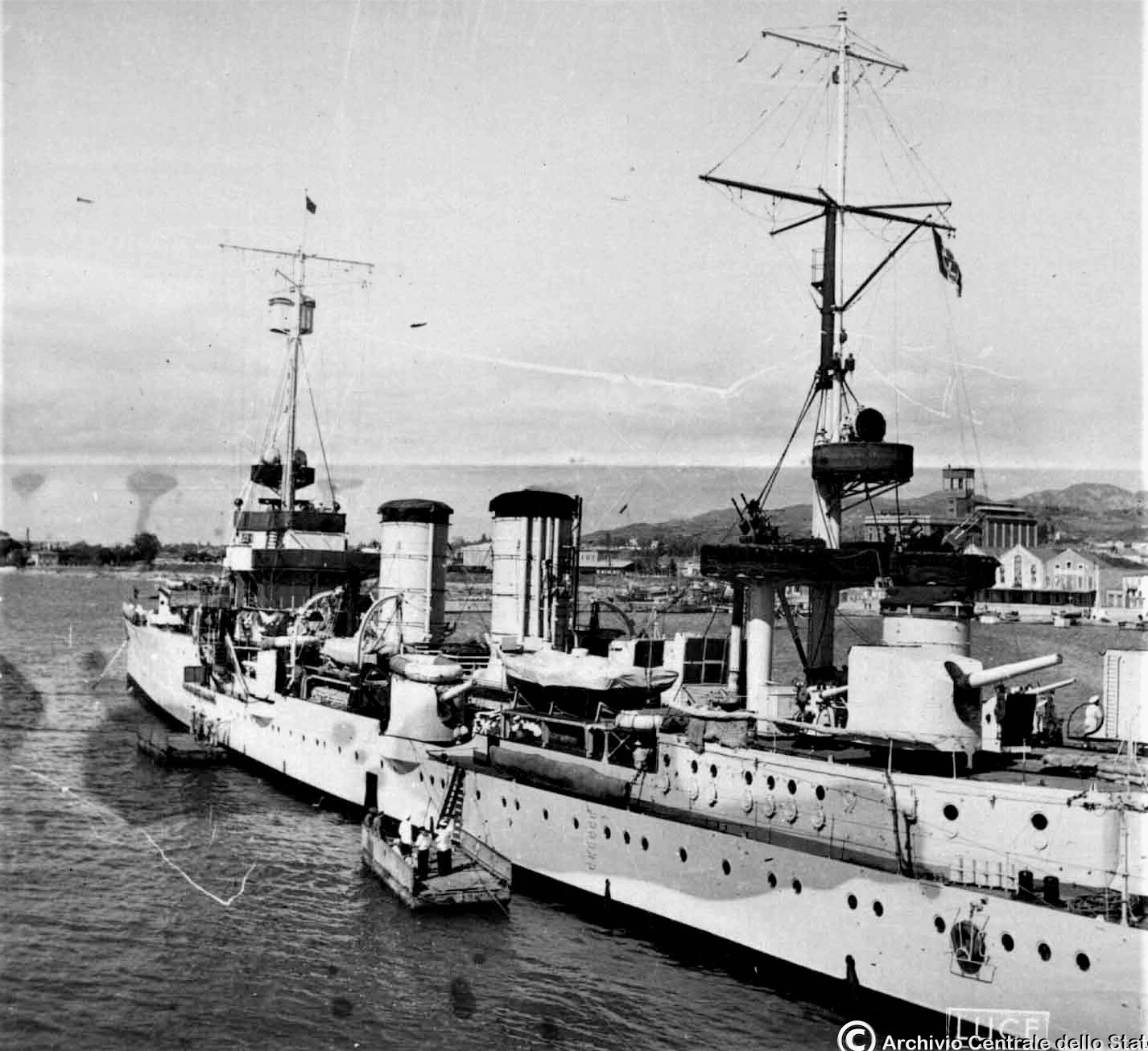

L’incrociatore leggero Bari late 1920s a

L’incrociatore leggero Bari late 1920s

L’incrociatore leggero Bari late 1920s, seen from the port side.

Bari, fotografiado en Venecia en el año 1931

Italian cruiser Bari, in Venice in the early 1930s. Colorized by Postales Navales

Cruiser Bari (ex SMS Pillau ) in floating dock, 1930s

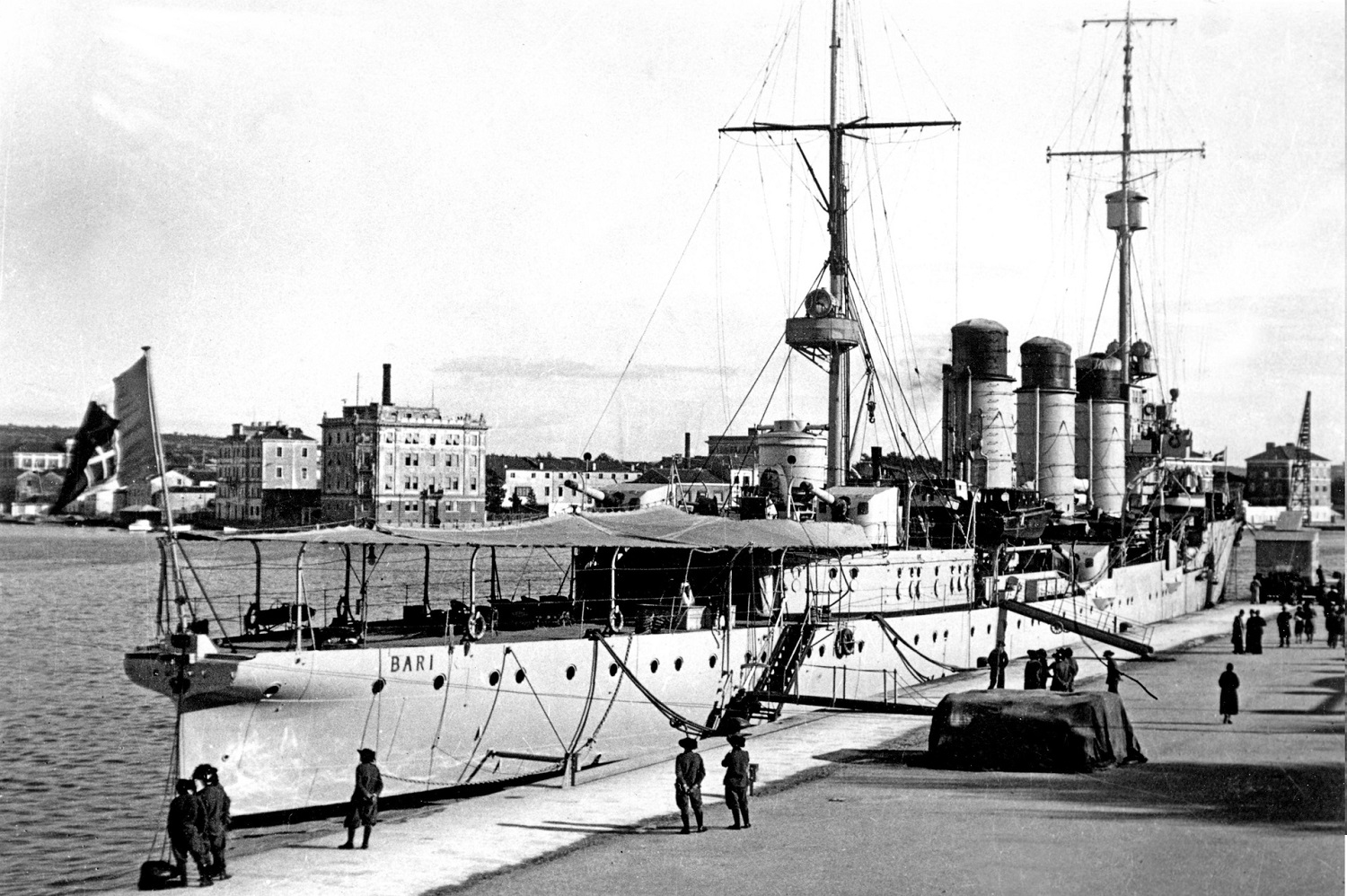

Italian light cruiser Bari (formerly the German SMS Pillau) moored at the pier in 1933

Italian Light Cruiser RM Bari pictured at Taranto c1929

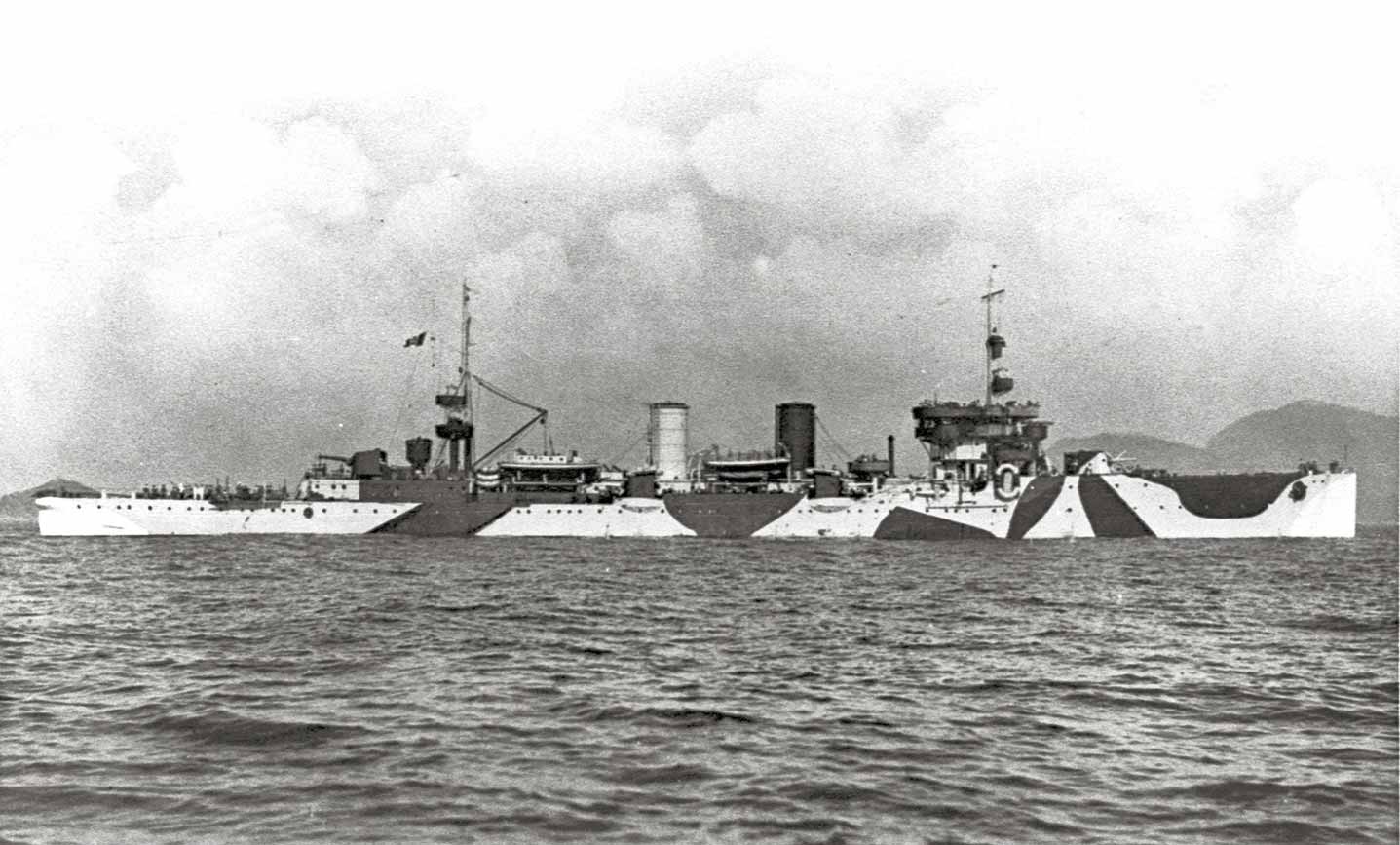

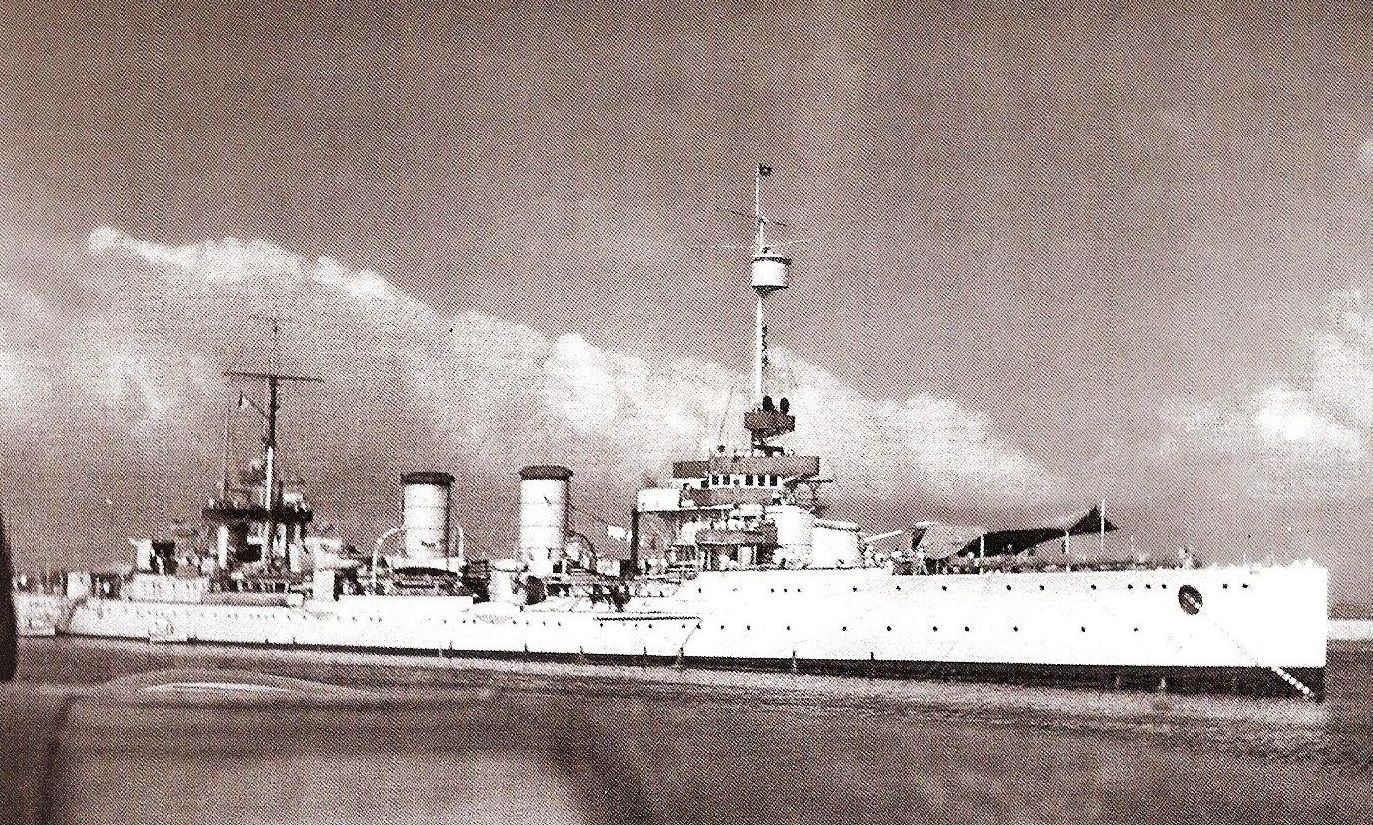

Bari would be extensively rebuilt in the early 1930s, including a new all-oil-fired engineering suite that almost doubled her range but dropped her top speed to 24 knots. This reconstruction included several topside changes to appearance as well as the addition of a few 13.2mm machine guns for AAA work.

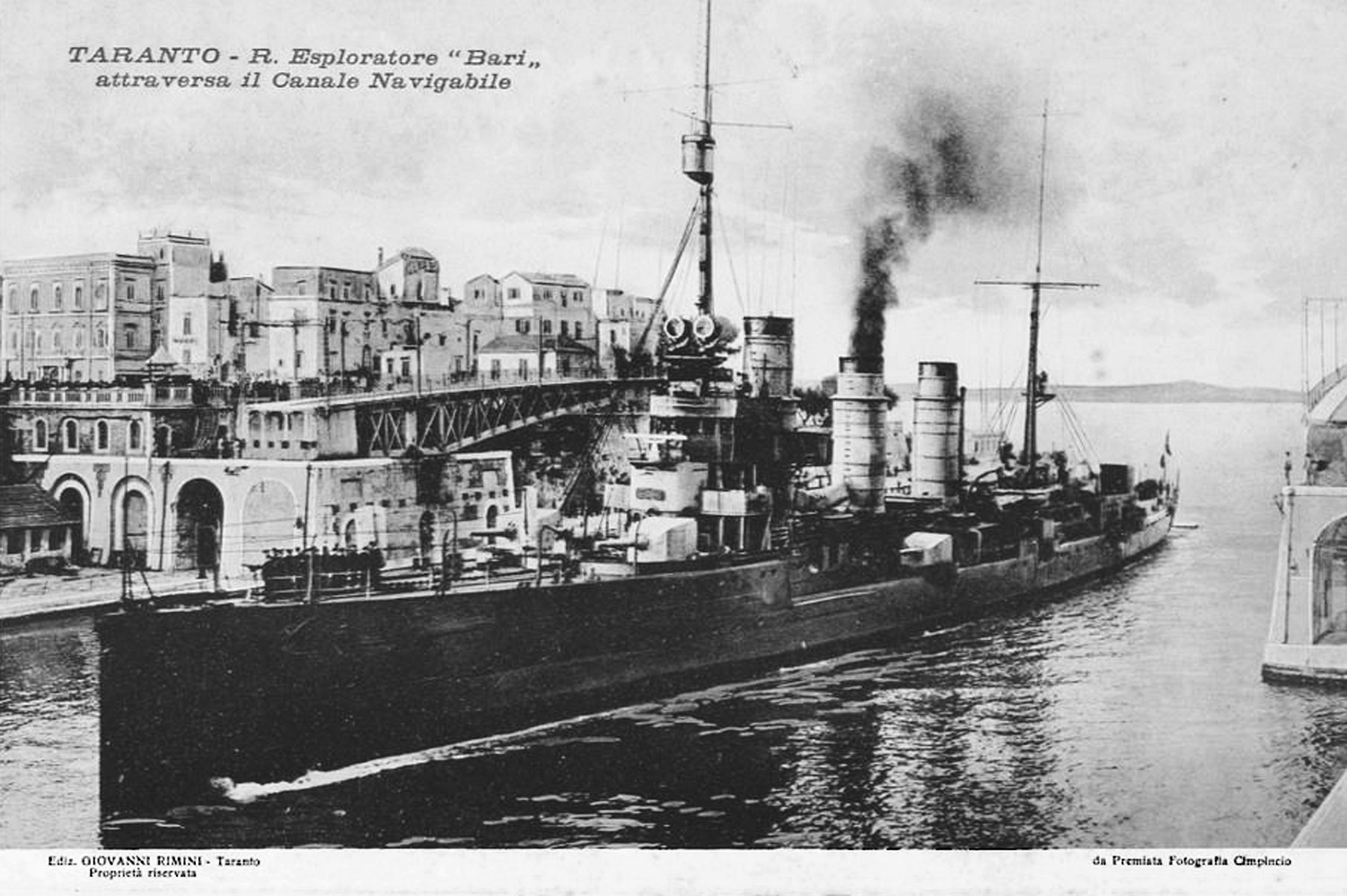

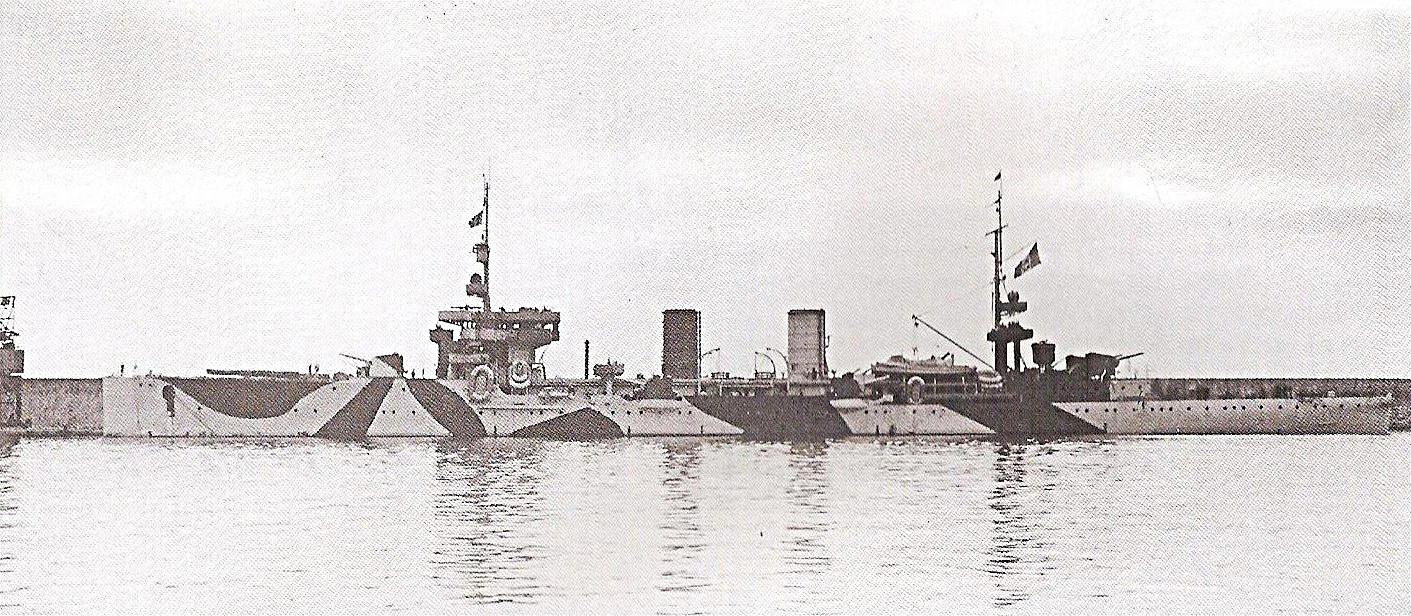

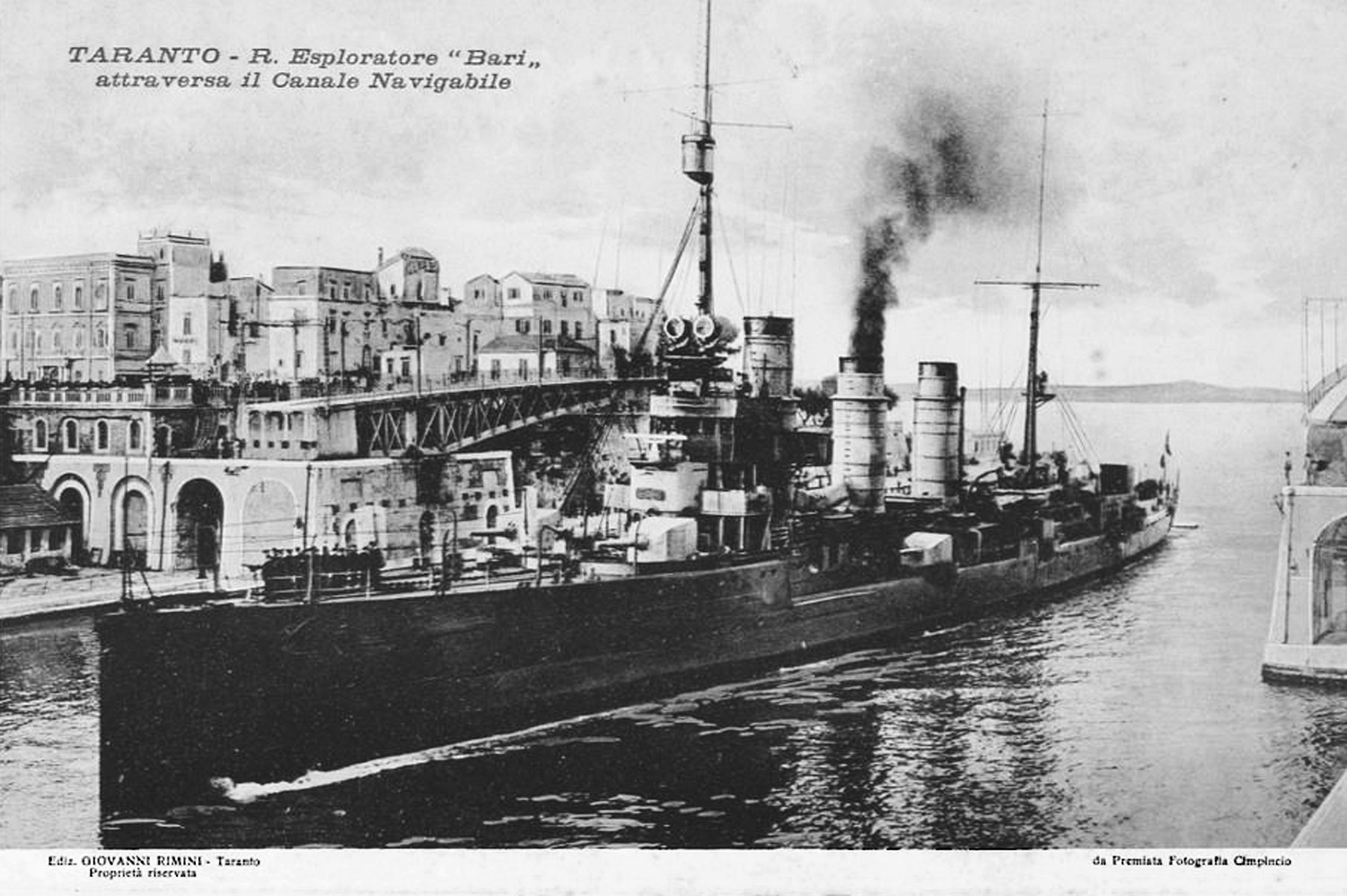

Bari crosses the navigable canal of Taranto after the second round of modification works, circa 1933-40. Compare this to the postcard image shown above taken at the same angle and place that shows her mid-1920s appearance

Bari in the 1931 Janes Fighting Ships

She took part in the Ethiopian war in 1935 and would remain in the Red Sea as part of the Italian East African Naval Command well into May 1938. She then returned home for further modernization at Taranto in which her torpedo tubes were removed and a trio of Breda 20mm/65cal Mod. 1935 twin machine guns were installed and two twin 13.2/76 mm Breda Mod. 31s.

Bari, as covered by the U.S. Navy’s ONI 202, June 1943.

When Italy joined WWII, Bari was soon sent to join the invasion of Greece where she conducted minelaying and coastal bombing missions in the Adriatic and the Aegean. She served as the flagship of ADM Vittorio Tur’s Special Naval Force (Forza Navale Speciale, FNS), an amphibious group that was used to occupy the Ionian Islands including Corfu, Kefalonia, Santa Maura, Ithaca, and Zakynthos. She would also participate in naval gunfire bombardment operations on the coast of Montenegro and Greece against partisans and guerrillas.

Bari in Patras in occupied Greece, as the flagship of the Forza Navale Speciale, May 1941

Another shot from the same above.

Bari moored in Patras, around 18 June 1941, with the ensign of Ammiraglio Comandante Alberto Marenco di Moriondo aboard.

ADM Tur and the FNS, with Bari still as his flag, would go on to occupy the French island of Corsica in November 1942 during the implementation of Case Anton, the German-Italian occupation of Vichy France after the Allied Torch landings in North Africa.

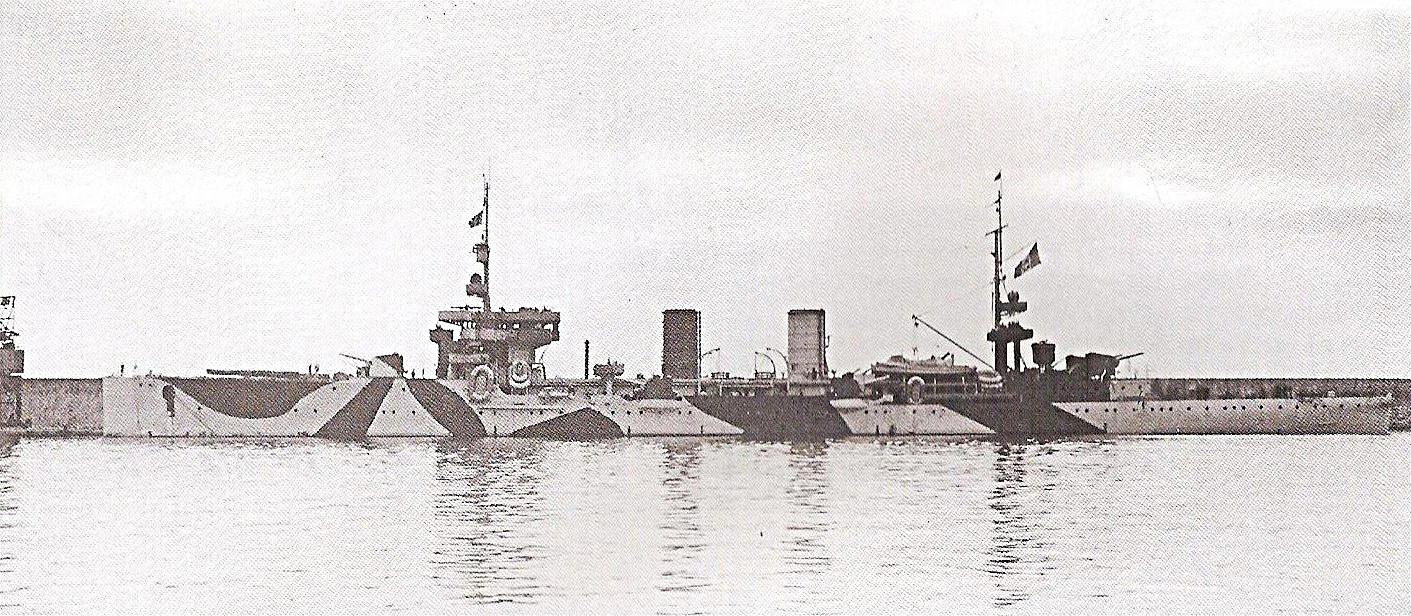

Bari anchored at the breakwater of the harbor of Bastia, Corsica, on 11 November 1942, as the flagship of the Forza Navale Speciale that was then occupying the island after Operation Torch.

The cruiser in Bastia on November 11, 1942, during the Italian landings. Note the steel-helmeted blackshirt troops in the foreground

In January 1943, with the FNS disbanded and ADM Tur assigned to desk jobs, Bari retired to Livorno where she was to be fitted as a sort of floating anti-aircraft battery, her armament updated to include a mix of two dozen assorted 90mm, 37mm, and 20mm AAA guns.

This conversion was never completed.

On 28 June 1943, she was pummeled by B-17s of the 12th Air Force and sank in the industrial canal at Livorno, deemed a total loss.

From 10 June 1940 to the sinking, the Bari had conducted 47 war missions and steamed 6,800 nautical miles.

After the Italian armistice, the Germans attempted to salvage the cruiser for further use but in the end wound up scuttling it once more in 1944. Post-war, she was stricken from the Italian naval list in 1947 and raised for scrapping the following year.

Epilogue

Very few remnants of these cruisers endure.

A painting by German maritime artist Otto Poetzsch was turned into a series of widely circulated Deutsches Reich postcards, used to depict both Pillau and Elbing.

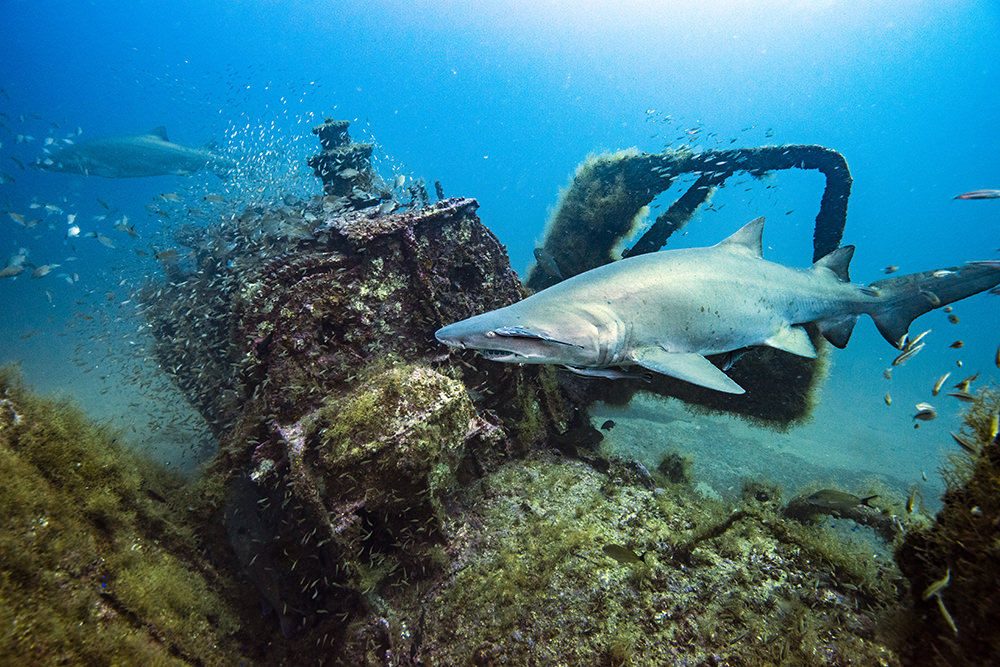

Elbing‘s wreck has been extensively surveyed and studied over the years and is generally considered to be in good shape after spending a century on the bottom of the Baltic. Besides her guns, she has china and glassware scattered around the hull.

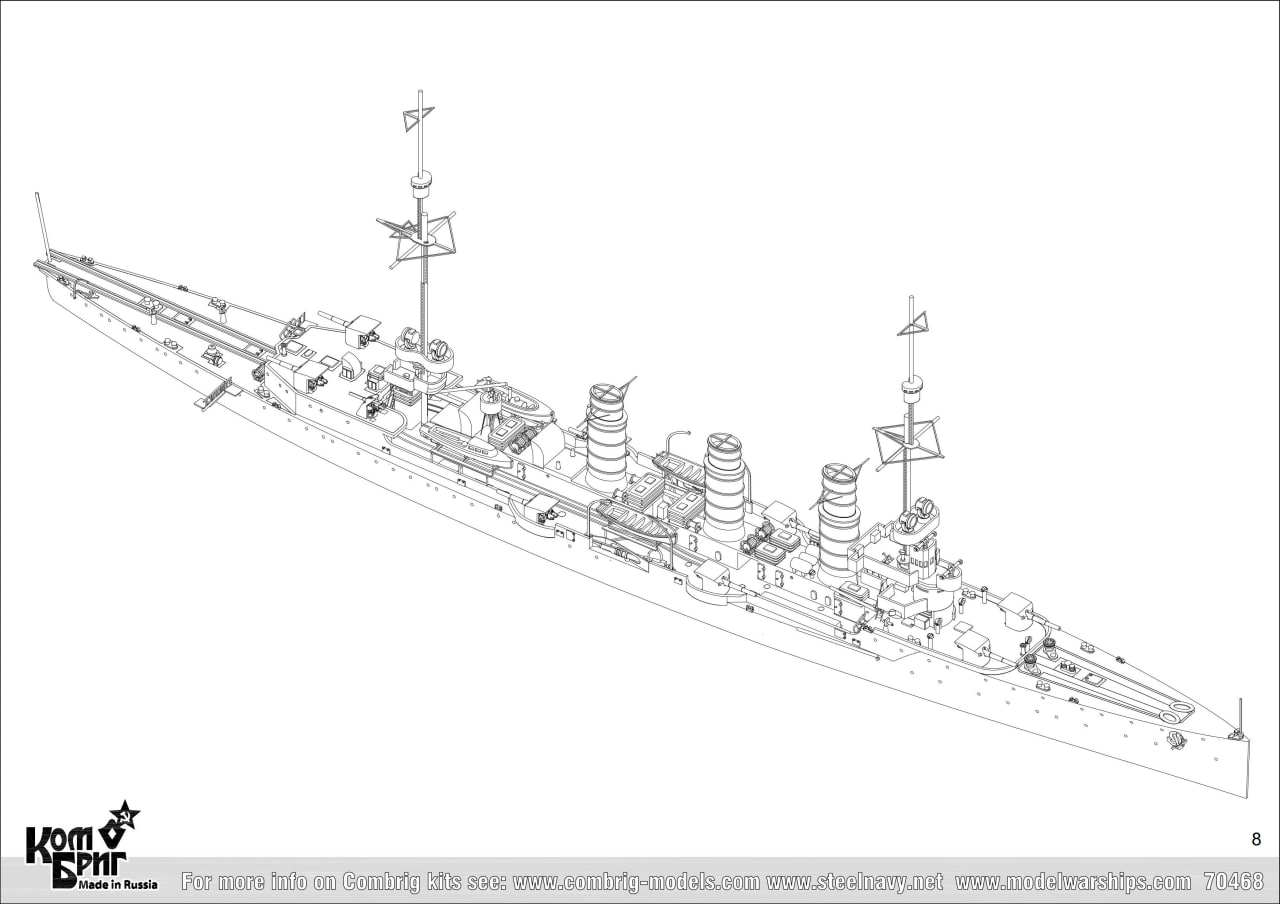

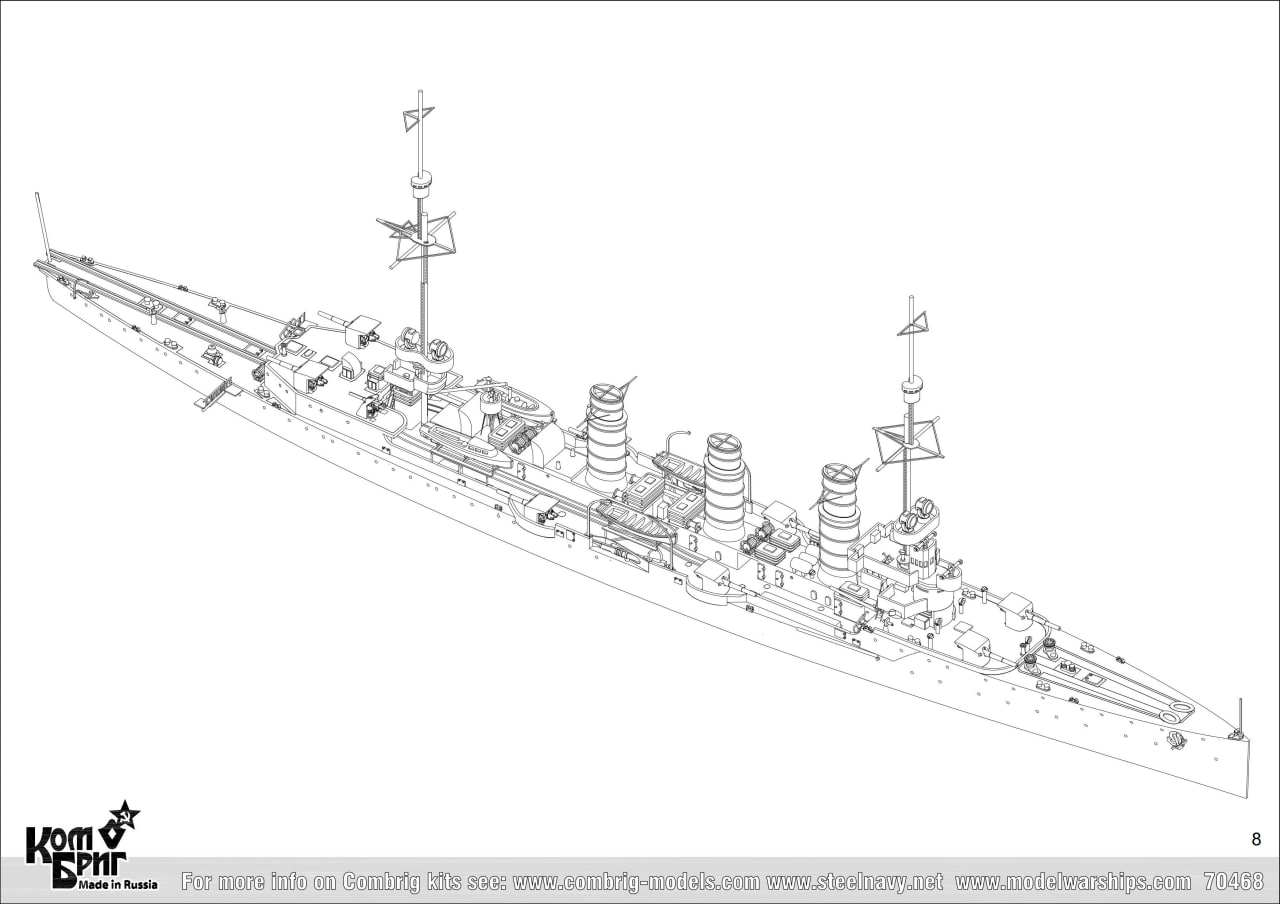

The Russian scale model firm Combrig makes a 1/700 scale kit of Pillau.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!