Warship Wednesday, March 27, 2024: That Time a Jeep Carrier Airshipped an Indian Army Brigade

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, March 27, 2024: That Time a Jeep Carrier Airshipped an Indian Army Brigade

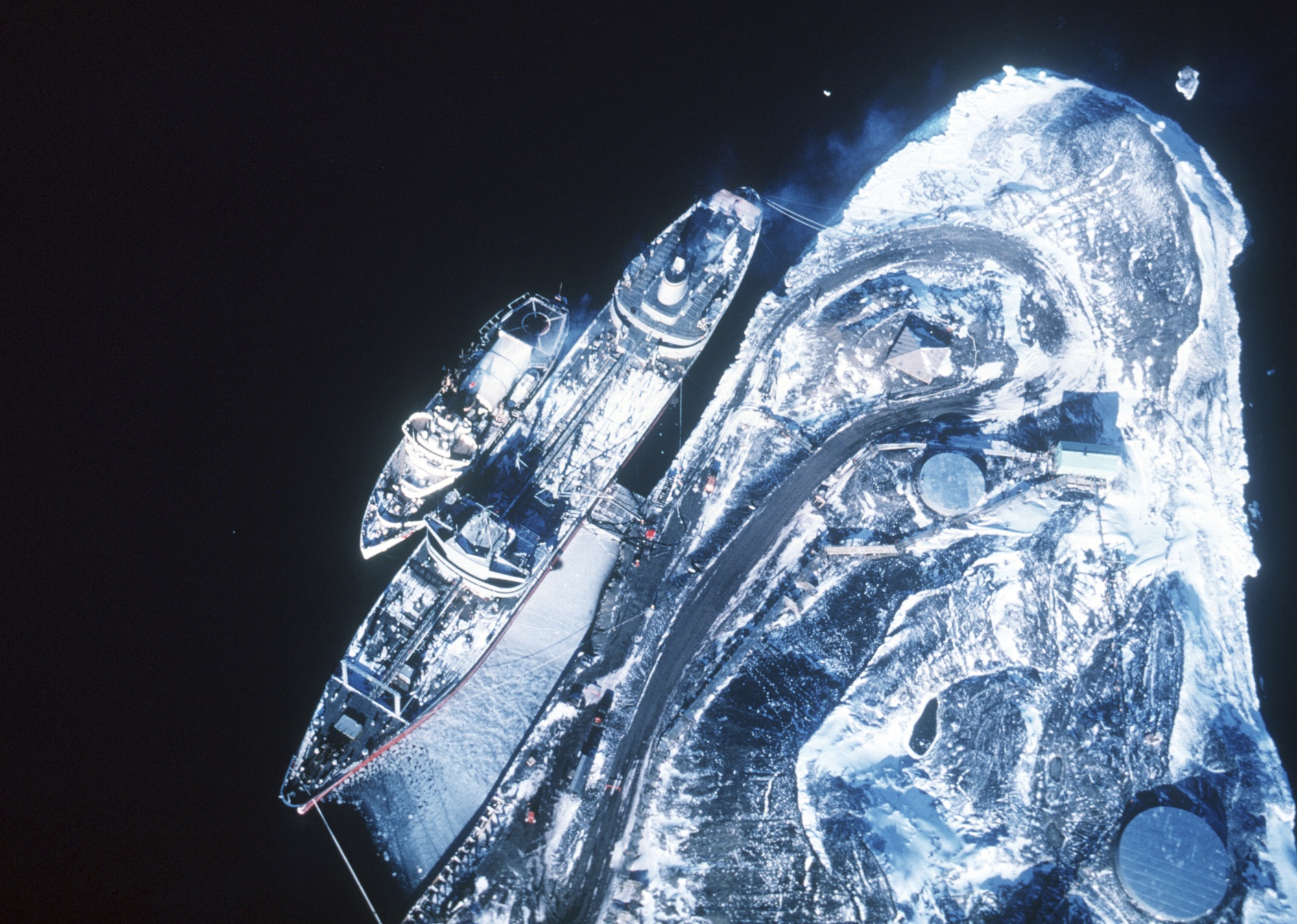

U.S. Defense Imagery VIRIN: 111-C-9093 by Van Scoyk (US Army), via the U.S. National Archives 111-C-9093

Above we see, on the center-line forward elevator of the Commencement Bay-class escort carrier USS Point Cruz (CVE-119), a great original Kodachrome showing a 25-man stick of Enfield-armed Indian Army troops ready to be airlifted ashore by five waiting H-19s to Panmunjom, Korea during Operation Platform on 7 September 1953. It was a remarkable achievement: vertically inserting 6,061 combat-ready Indian troops some 30 miles inshore in 1,261 helicopter sorties without losing a single man or bird.

You’ve never heard of Operation Platform? Well, stand by for the rundown.

The Commencement Bays

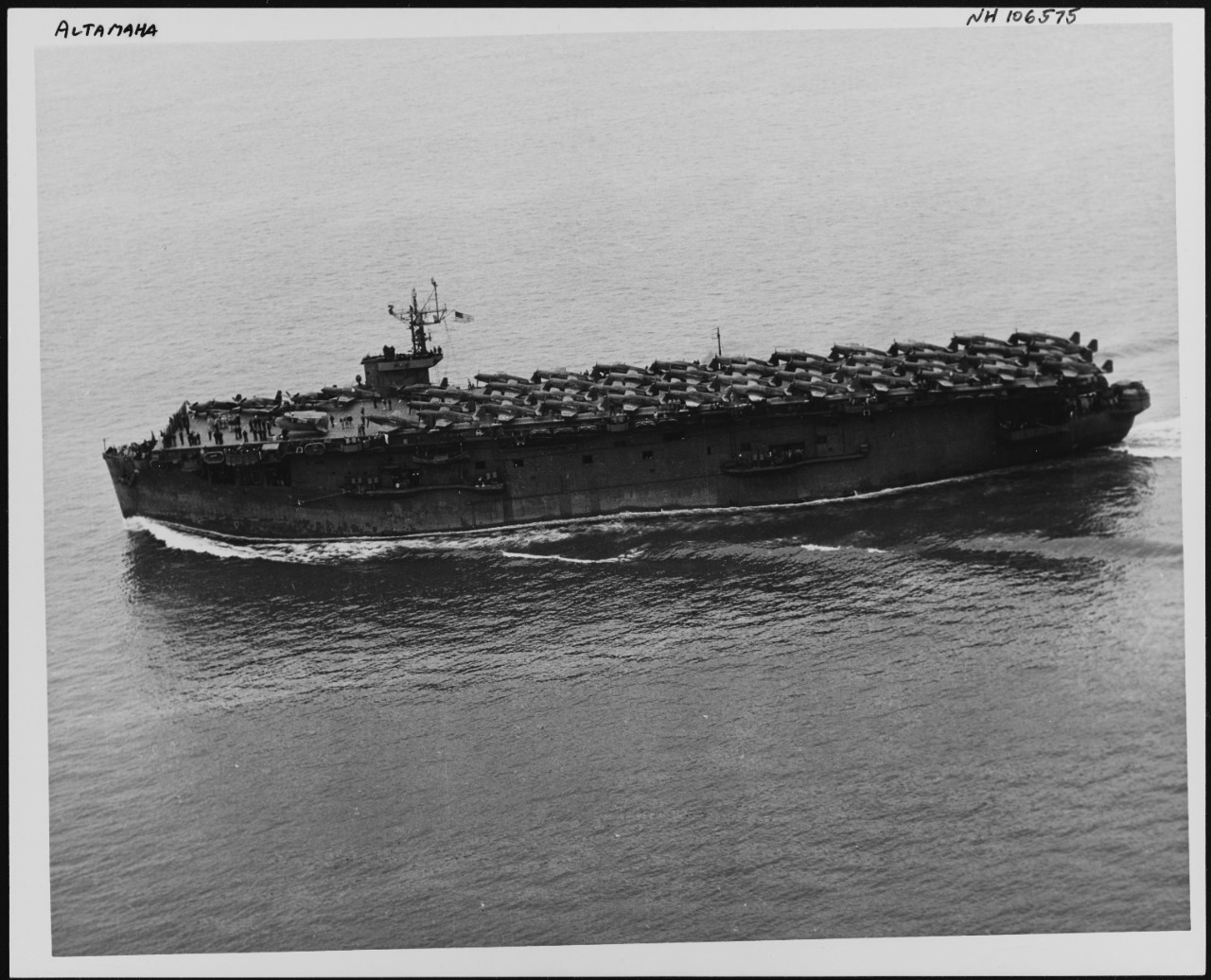

Of the 130 U.S./RN escort carriers– merchant ships hulls given a hangar, magazine, and flight deck– built during WWII, the late-war Commencement Bay class was by far the Cadillac of the design slope. Using lessons learned from the earlier Long Island, Avenger, Sangamon, Bogue, and Casablanca-class ships. Like the hard-hitting Sangamon class, they were based on Maritime Commission T3 class tanker hulls (which they shared with the roomy replenishment oilers of the Chiwawa, Cimarron, and Ashtabula-classes), from the keel-up, these were made into flattops.

Pushing some 25,000 tons at full load, they could make 19 knots which was faster than a lot of submarines looking to plug them. A decent suite of about 60 AAA guns spread across 5-inch, 40mm, and 20mm fittings could put as much flying lead in the air as a light cruiser of the day when enemy aircraft came calling. Finally, they could carry a 30-40 aircraft airwing of single-engine fighter bombers and torpedo planes ready for a fight or about twice that many planes if being used as a delivery ship.

Sounds good, right? Of course, had the war run into 1946-47, the 33 planned vessels of the Commencement Bay class would have no doubt fought kamikazes, midget subs, and suicide boats tooth and nail just off the coast of the Japanese Home Islands.

However, the war ended in Sept. 1945 with only nine of the class barely in commission– most of those still on shake-down cruises. Just two, Block Island and Gilbert Islands, saw significant combat, at Okinawa and Balikpapan, winning two and three battle stars, respectively. Kula Gulf and Cape Gloucester picked up a single battle star.

With the war over, some of the class, such as USS Rabaul and USS Tinian, though complete were never commissioned and simply laid up in mothballs, never being brought to life. Four other ships were canceled before launching just after the bomb on Nagasaki was dropped. In all, just 19 of the planned 33 were commissioned.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Meet Point Cruz

Our boat was initially named Trocadero Bay— for a strait in the eastern part of Bucareli Bay in the Prince of Wales archipelago of Alaska– in line with the “Bay” naming convention at the time for escort carriers. Laid down at Todd Pacific Shipyards in Tacoma on 4 December 1944, she was subsequently renamed Point Cruz to honor the decisive three-day battle in November 1942 on Guadalcanal.

Launched a week after VE Day, her construction ended just after VJ Day and she was commissioned on 16 October 1945, a war baby completed too late for her war.

Following trials and shakedowns off the West Coast, Point Cruz spent about a year shuttling aircraft to forward bases around the Western Pacific before reporting to Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in March 1947 for inactivation. Decommissioned three months later, she was laid up in the Pacific Reserve Fleet at Bremerton without firing a shot in WWII.

Bremerton, Washington, aerial view of the reserve fleet berthing area at Puget Sound. 25 October 1951. Ships present include USS Indiana (BB-58); USS Alabama (BB-60); USS Maryland (BB-46); USS Colorado (BB-47); and USS West Virginia (BB-48). Four Essex (CV-9) class CVs one Commencement Bay (CVE-105) class CVE in the foreground– possibly Point Cruz– one Independence (CVL-22) class CVL, as well as numerous CA, CL, DD, DE, and auxiliary-type ships are also visible. 80-G-435494

Headed to Korea

With the sleepy early Cold War peace shattered when the Norks crossed the 38th Parallel in 1950, the Navy was soon reactivating gently used ships from mothballs to sustain the high tempo carrier, fire support, and amphibious warfare operations off the Korean coast. Point Cruz was dusted off and recommissioned on paper on 26 July 1951 but would spend the next 18 months in an extensive overhaul modifying her for use as an ASW Hunter-Killer Group carrier.

Our girl only got underway for Sasebo in January 1953. There, on 11 April, she would embark the scratch air group consisting of F4U-4B Corsairs of VMF-332 and TBM-3W/3E Avengers of VS-23, along with a HO3S-1 helicopter det from HU-1 for C-SAR, and would go on to patrol the Korean coast for the last four months of the conflict.

Vought F4U-4 Corsair fighters assigned to U.S. Marine Corps attack squadron VMA-332 Polka-dots aboard the escort carrier USS Point Cruz (CVE-119) on 27 July 1953 during a deployment to Korea. “Replacing the VMF-312 Checkerboards, which had a red and white checkerboard painted around the engine cowlings, VMA-332, somewhat mockingly, adopted the red polka dots on white background. The design was reminiscent of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker’s ‘Hat in the Ring’ Squadron of World War I. The addition of the hat and cane was derived from the squadron tail letters (MR), being the abbreviation of ‘mister’, and feeling they were gentlemen in every regard, the hat and cane were adopted as accouterments every gentleman has. It was then that the squadron picked up the nickname VMA-332 Polkadots.” Photo by Cpl. G.R. Corseri, USMC

USS Point Cruz (CVE 119) at sea, east of Japan, 23 July 1953. She has anti-submarine aircraft on her flight deck including seven TBM-3S and TBM-3W Avengers and one HO4S helicopter. 80-G-630786

Op Platform

When the Korean War Armistice came about, our little flattop was tasked with her role in Operation Platform (Operation Byway by the U.S. Army and Operation Patang/Kite by the Indian Army), airlifting Indian troops to the Panmunjom neutral buffer zone– without touching South Korea– to supervise the neutral repatriation of some 22,959 North Korean and Chinese POWs, many of which didn’t want to return to their home countries. It would take nine months for these men to either be sent back to their homeland or a neutral country under the agreement that halted the war.

The “hop, skip, and a jump” logistics of Platform/Byway/Patang began with the “hop” of six Allied transports (two Indian, two American, and two British) carrying 6,061 men of the hand-picked five-battalion 190th Indian Brigade from Japan under Brigadier Rajinder Singh Paintal, a formation that would become the post-war Custodian Force India (CFI).

Consisting of some of the most storied units of the Indian Army, many of these men had seen combat in WWII and were professional soldiers. The force was under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Shankarrao Pandurang Patil Thorat, KC, DSO, a long-serving Sandhust-educated gentleman officer who had picked up his well-deserved DSO as c/o of 2/2 Punjab in the hell of Kangaw on the Arakan coast of Burma, against the Japanese in 1945, and subsequently earned his brigadier’s straps while under British service. Singh, the brigade commander, had likewise been through Sandhurst and, as a captain with the 4/19 Hyderabad Regiment, was captured at Singapore in 1942 and endured four years as a POW in Japanese camps.

Most had to be brought to Korea via a USAF airbridge from India to Japan via Calcutta and Saigon.

315th Air Division, Far East–One hundred paratroopers of the Indian Paratroop Battalion board a U.S. Air Force 374th Troop Carrier Wing C-124 “Globemaster” at Dum Dum Airport, Calcutta, en route to Korea to serve with other Indian Custodial Forces in the demilitarized zone. Five hundred and seventy-five Indian troops were airlifted from Calcutta to southern Japan in the three-decked planes in 20 flying hours, with only two stops for refueling. It was the first Globemaster landing at either Calcutta or Saigon, Indo-China, where a refueling stop was made. The Indian paratroopers were brought to southern Japan, where they were scheduled to transfer to a surface vessel. NARA – 542320

The “skip” would see the troops transferred from their troopships to an anchored Point Cruz without landing in South Korea proper– as Rhee thought they were basically co-opted by the Communists– via U.S. Navy LCUs from Inchon.

Then came the final “jump” which was the movement ashore to Panmunjom from Point Cruz’s flight deck via Sikorsky S-55 Chickasaw H-19/HRS-2 helicopters, five aircraft at a time, each carrying five man sticks (each stick limited to 2,000 pounds including men and gear). The choppers came from the Army’s 1st Transportation Army Aviation Battalion (Provisional), which consisted of the 6th and the 13th Helicopter Companies; and the “Greyhawks” of Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron 161 (HMR-161), with an Army colonel as the overall “air boss.”

August 27 saw Point Cruz arrive at Inchon and fly off her fixed-wing aircraft that afternoon. The 28th and 29th saw the Army and Marine helicopter pilots come aboard for orientation.

It was decided that the five-helicopter blocks would form up, land, and take off as a unit for safety, then deliver their charges ashore. Lifejackets would be issued to the troops from a pool just before loading, then collected at the landing zone ashore for reissue to the next group.

The airlift started on 1 September with the first Indian troops shipped over to Point Cruz from the British troopship HMT Empire Pride. Some 437 men were airlifted that afternoon in 89 sorties. The next day 907 men in 186 flights– including deputy brigade commander Brig Gen. Gurbuksh Lingh and the entire 6th Bn Jat Regiment– followed by 73 sorties on 3 September carrying 360 men for a composite total of 1,704 troops carried ashore in 348 flights.

The British steamer HMT Dilwara arrived off Inchon on 6 September from Japan and started transferring men via LCU to Point Cruz, with the airlift starting up again on the 7th with 979 Indian troops, primarily of the 3rd Bn Dogra Regiment, carried inshore in 196 flights.

When the Indian ship Jaladurga steamed into Inchon a few days later, followed by the American MSTS troopship USNS General Edgar T. Collins (T-AP-147), 1,555 Indian troops were transferred aboard Point Cruz and then carried into the DMZ in 328 flights. These were primarily from the 5th Bn Rajputana Rifles and of the brigade’s HHC.

The final phase saw the Indian ship Jalagopal and the transport USS Menifee (APA-202) transfer 1,823 Indian troops to Point Cruz via boat, which were then carried into the DMZ in 389 sorties between the 28th and the 30th. These troops included the whole of the 3rd Bn Garhwal Rifles and the 2nd Bn Parachute Regiment (Maratha), along with support personnel.

Platform was a tremendous success in terms of moving the 190th ashore, especially considering the military use of the helicopter was in its infancy and the first U.S. military rotary wing shipboard trials had only been conducted a decade prior.

Twilight

Wrapping up her involvement in moving the Indians to the Panmunjom buffer zone, Point Cruz reembarked her Corsairs and Avengers and resumed patrols in the tense waters around Korea. Headed back to San Diego, she landed her aircraft on 18 December 1953 and began an overhaul there that would last until April 1954.

A West Pac cruise from 27 April to 23 November saw her embark the short-lived 11-ton Grumman AF-2W/2S Guardians of VS-21– the first purpose-built ASW aircraft system to enter service in the U.S. Navy aircraft, along with a HO4S-3 helicopter det of HS-2.

A follow-on West Pac cruise (24 August 1955- February 1956), as the flagship of Carrier Division 15, would see Point Cruz with another new ASW platform, the twin-engined 12-ton S2F-1 Tracker, the largest Navy aircraft to operate from CVEs. This cruise would also see one of the final carrier deployments of Corsairs, with a det of radar-equipped F4U-5N night fighters of Composite Squadron 3 (VC-3) “Blue Nemesis” embarked to give the flattop some limited air-to-air capability.

USS Point Cruz (CVE-119) underway with a Sikorsky HO4S-3S of Helicopter Antisubmarine Squadron HS-4 and Grumman S2F-1 Trackers of Antisubmarine Squadron VS-25 on board, 1955. U.S. Navy photo USN 688159

USS Point Cruz (CVE-119) is underway with a Sikorsky HO4S-3S of HS-4 and four S2F-1 Trackers of VS-25 aboard, 1955. Note she still has her 40mm twin Bofors installed including at least one that is radar-guided. U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation photo No. 1996.488.035.048

Point Cruz departed Yokosuka on 31 January 1956 and arrived in Long Beach in early February for inactivation at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Decommissioned on 31 August 1956, CVE-119 was placed in the Bremerton Group of the Pacific Reserve Fleet.

Vietnam

While in a reserve status, Point Cruz was redesignated as an Aircraft Ferry (AKV-19), on 17 May 1957.

With the massive build-up of forces in Southeast Asia, Point Cruz was taken out of mothballs, reactivated, on 23 August 1965, and placed under the operational control of the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS) as T-AKV 19 in September of that year. By the end of that year, MSTS had over 300 freighters and tankers supplying Vietnam, with an average of 75 ships and over 3,000 merchant mariners in Vietnamese ports at any time.

Crewed by civilian mariners, USNS Point Cruz spent the next four years in regular aircraft ferry service from the West Coast to the Republic of Vietnam and other points Far East, typically loaded with Army helicopters– something she was quite familiar with. In this tasking, she joined at least five fellow CVEs taken out of mothballs– USNS Kula Gulf, Core, Card, Croatan, and Breton.

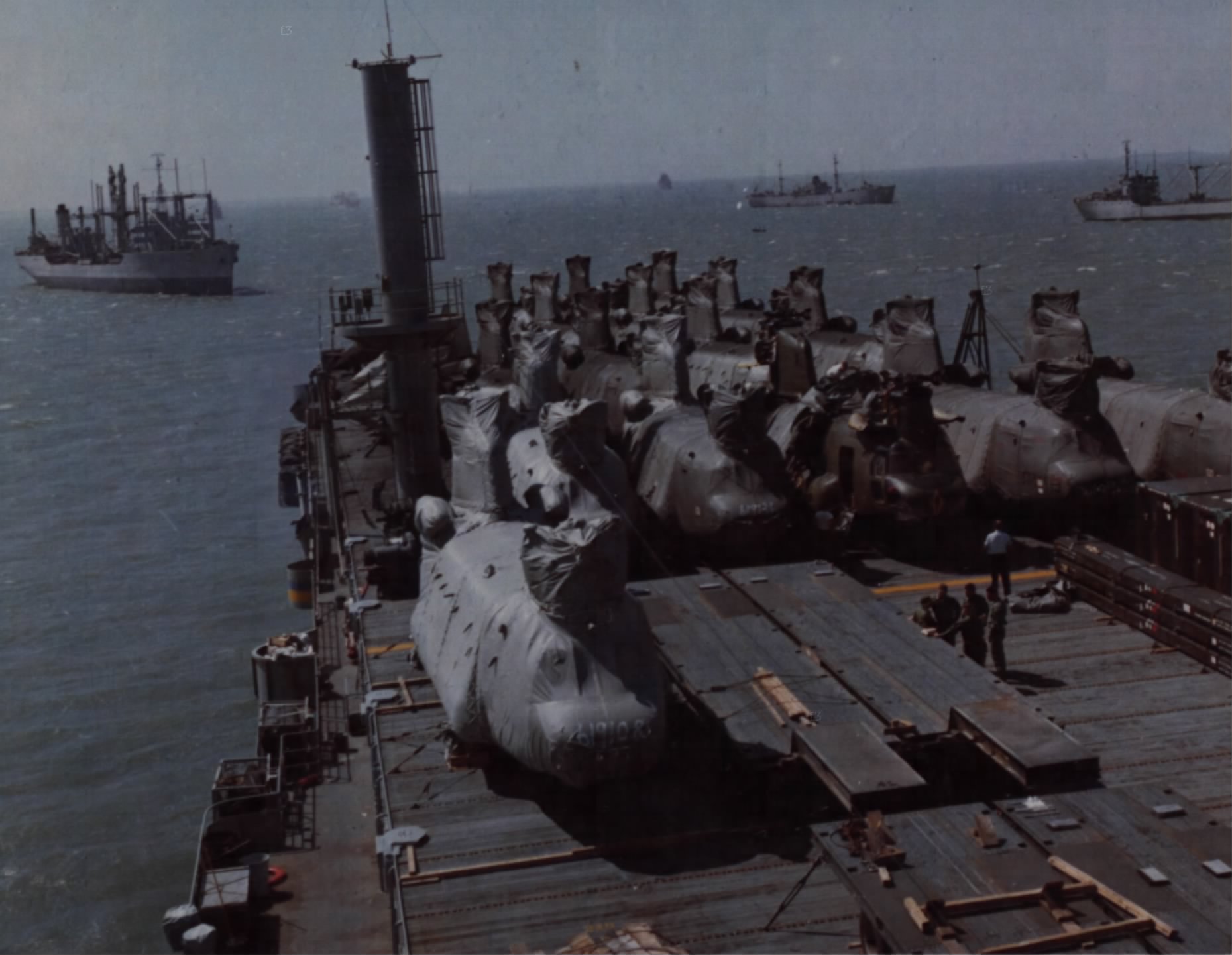

Men of the 271st Aviation Company, 13th Battalion, 164th Group, 1st Aviation Brigade, remove the protective cocoon from the first of the 16 CH 47B Chinook helicopters sitting on the deck of the USS Point Cruz 23 February 1968 NARA photo 111-CCV-105-CC47174 by SP4 Richard Durrance

A CH-47B of the 271st, Point Cruz, same date and place as above. NARA photo 111-CCV-638-CC47180 by SP4 Richard Durrance.

She also carried a number of jets that she could never have operated.

USNS Point Cruz delivered aircraft to Yokosuka, Japan in the mid-1960s. Types onboard appear to be A-1 Skyraiders, a T-33 Tweet, an F-104 Starfighter, and F-4 Phantom IIs. The F-104 and F-4s were possibly bound for the JASDF, the other aircraft for use in Vietnam.

Tug Smohalla (YTM-371) alongside the Aircraft Transport USNS Point Cruz (T-AKV 19) at Yokosuka, Japan, 11 June 1966. Via Navsource

Placed out of service on 6 October 1969, the ex-Point Cruz was advertised in a scrap auction in February 1971 that was secured by the Southern Scrap Material Co. New Orleans for a high bid of $108,888.88.

Removed from Naval custody on 18 June 1971, her scrapping was completed sometime in 1972.

Epilogue

The plans and some images for Point Cruz are in the National Archives.

Of the rest of the Commencement Bay class, most saw a mixed bag of post-WWII service as Helicopter Carriers (CVHE) or Cargo Ships and Aircraft Ferries (AKV). Most were sold for scrap by the early 1970s with the last of the class, Gilbert Islands, converted to a communication relay ship, AGMR-1, enduring on active service until 1969 and going to the breakers in 1979. Their more than 30 “sisters below the waist” the other T3 tankers were used by the Navy through the Cold War with the last of the breed, USS Mispillion (AO-105), headed to the breakers in 2011.

As for Operation Platform, one of the Army H-19C Hogs involved (51-14272/MSN 55225), one of the four known surviving aircraft of the type in the world, is preserved at the U.S. Army Aviation Museum in Alabama. Likewise, a Marine HRS-2, marked as 127834, is in the main atrium of the National Museum of the Marine Corps, portrayed disembarking a machine gun unit onto a Korean War position.

The CFI, on completion of their mission in May 1954, returned to India by sea and all five battalions of the 190th Brigade are still in existence in today’s Indian Army. As a testament to their success in safeguarding the controversial Chinese and North Korean POWs, some 86 of the latter as well as two South Koreans elected to immigrate to India with their protectors when the latter sailed for home.

The Marine unit that took them ashore, HMR-161, still exists as VMM-161.

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!