Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places. – Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, May 25, 2022: I’m Not as Good as I Once Was, But…

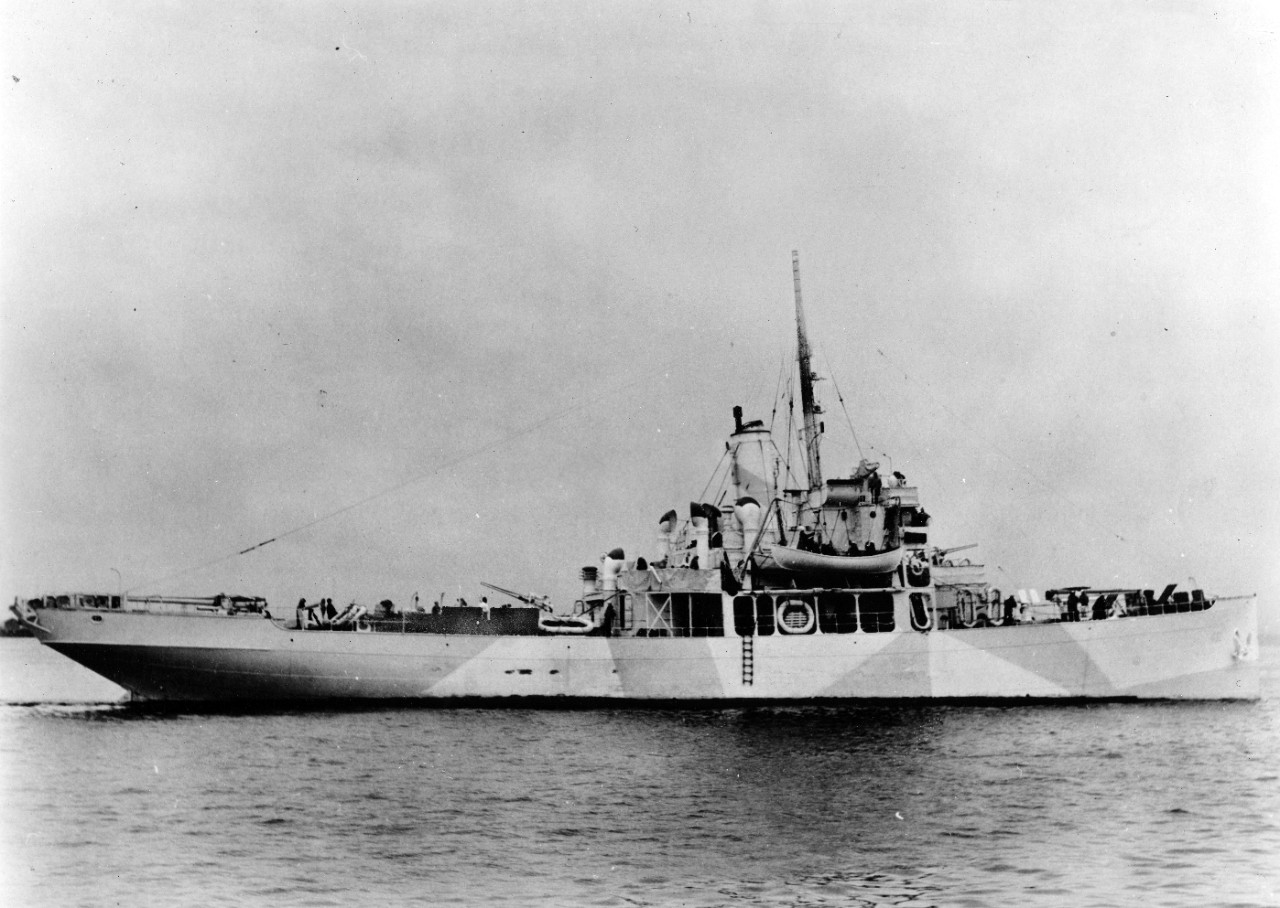

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. NH 43761-A

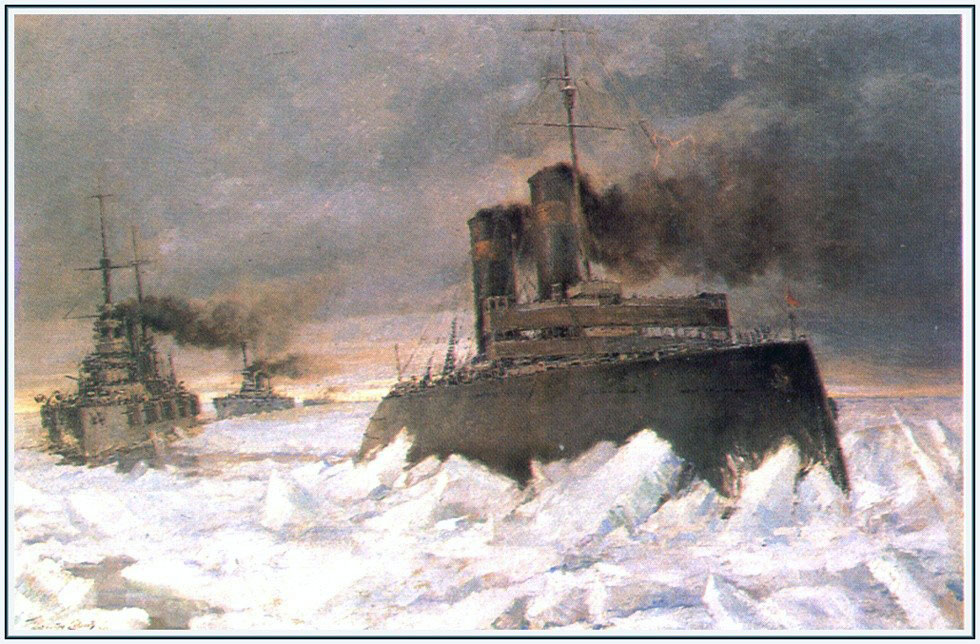

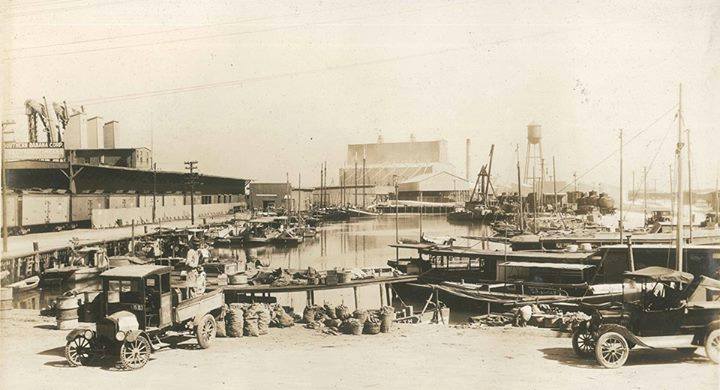

Above we see USS Worden (Torpedo Boat Destroyer # 16) of the Truxtun class of such green-painted stiletto-hulled vessels, in the Hampton Roads area in 1907. An unidentified white-hulled four-stack armored cruiser is visible in the left distance. Seen as a modern warship on the forefront of technology at the time, Worden was part of the force welcoming the Great White Fleet home from overseas and would later be shown off to eager crowds at the Hudson-Fulton Celebration two years later. Well past her prime in 1942, Worden would still be ready to serve.

The three Truxtuns were among the original 16 TBDs authorized by Congress, during the SpanAm War, on 4 May 1898, and were the most advanced of the designs. Just 259 feet long overall, they could float in a single fathom of water due to their 600-ton (full load) displacement. Powered by four Thornycroft boilers powering twin VTE engines, they had 8,300 hp on tap and could make 29.9 knots. Equipped with two 3″/50s 12-pounders and a full half-dozen 57mm 6-pounders, the Truxtuns were seen as capable of making short work of lighter torpedo boats while their two single 18-inch Whitehead torpedo tubes– on turnstiles aft to stern– allowed them to substitute for the latter while keeping up with a blue water fleet.

Truxtun class via Oct 1902 Marine Engineering Magazine

Our subject was the first warship named for RADM John Lorimer Worden, USN. Appointed a midshipman at age 18 in 1834, he gained fame as the first skipper of the USS Monitor and commanded that famed “cheesebox on a raft” in the first clash of armored warships, fighting the Confederate ram Virginia (ex-USS Merrimack) to a standstill in 1862. Worden later attained the rank of Rear Admiral while serving as the Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy in the early 1870s and was the first president of the United States Naval Institute.

Retired in 1886 after 52 years of service, RADM Worden was granted sea pay for life by a grateful Congress, passing in 1897.

All three of the Truxtun class– Truxtun (DD-14), Whipple (DD-15), and Worten (DD-16) were ordered from the Maryland Steel Company at Sparrows Point in one block. Laid down side-by-side in November 1899 and launched on the same day in 1901, they were accepted and commissioned by the Navy in a staggered program in the last quarter of 1902, with Worten joining the fleet on New Year’s Eve. Like Worten, all were named for noted naval figures, a practice gratefully still followed for most American tin cans for the past 120 years.

Worden passed her final acceptance test on 18 July 1903 and began duty with the 2nd Torpedo Flotilla, based at Norfolk.

On her builder’s trials in September 1902 off Barren Island, Worden did better than her 29-knot sisters, hitting 30.50 knots. She remained one of the speediest ships in the fleet. In June 1907, she walked away from her competitors on a 250-mile speed and service test from New York’s Scotland Light to Hampton Roads, besting five other destroyers.

USS Worden Description: (Torpedo Boat Destroyer # 16) Underway during the North Atlantic Fleet review, 1905. Photographed by the Burr McIntosh Studio. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation, Rodgers Collection. NH 91222

A great period image of officers and crew of USS Worden (DD-16), 1906. Judging from the single torpedo tube and the elevated 3″/50, this is over the destroyer’s stern. As she only carried a 50-60 man crew, this is likely the whole complement. Note there are just two officers up front– an ensign and a lieutenant– and a bow-tie-wearing boatswain in the background. Also note the African-American sailor by the gun ring and the mix of uniforms including both blues and whites, flat caps and Donald Ducks, topside gear, and stokers’ utilities. Navy Museum Northwest Collection. Catalog #: 2014.36

However, the fleet was low on men and high on hulls, having gone through a massive expansion in the early 20th Century under Teddy Roosevelt. With that, the still-young destroyer was placed in reserve at the Norfolk Navy Yard in November 1907, a role she would maintain for the next seven years except for a brief reactivation to take part in the Hudson-Fulton Celebration in the summer of 1909, and a stint as a pier-side trainer for the Pennsylvania Naval Militia at Philadelphia in 1912.

Hudson-Fulton Celebration September-October 1909 Crowd observes warships anchored in the Hudson River, off New York City, during the festivities. The four-funneled destroyer in the left foreground is USS Worden (Destroyer # 16), with several torpedo boats anchored astern. The British armored cruisers beyond are HMS Argyll (at left) and HMS Duke of Edinburgh (right center). Collection of Chief Quartermaster John Harold, USN. NH 101529

In 1914, she was detailed as a tender to the Atlantic Fleet Submarine Force with a job moonlighting as a recruiting prop, continuing in such as role until the U.S. entered the Great War in April 1917. In the meantime, on 24 February 1916, the Navy Department ordered that destroyers No. 1 through 16 were “no longer serviceable for duty with the fleet” and reclassified them as “coast torpedo vessels.”

War!

Shaking off her submarine tender duties, the reactivated Worden joined Division B, Destroyer Force, and spent the rest of 1917 in New York.

Meanwhile, the British Admiralty decided it was finally time to try the convoy system to help curb the onslaught of the German U-boat scourge. If only they could get hundreds of new escorts to help with that at all levels…

In early 1918, the “obsolete” Worden, refitted for “distant service,” got underway for Europe in company with a whole crew drawn from the original 16 destroyers that had been downgraded to CTVs. This included Hopkins (Coast Torpedo Vessel No. 6), Macdonough (Coast Torpedo Vessel No. 9), Paul Jones (Coast Torpedo Vessel No. 10), and Stewart (Coast Torpedo Vessel No. 13). The little five-pack steamed, via Bermuda, to Ponta Delgada in the Azores, arriving at the end of January.

Reaching Brest on the 9 February, Worden then started clocking in with her associates in the business of escorting coastal convoys and hunting for the Hun. As summed up by DANFS, “During the remaining nine months of World War I, Worden maintained a grueling schedule escorting convoys between ports on the French coast.”

Her sisters Truxtun and Whipple, which had arrived in Brest in late 1917, had much the same war experience, coming to the rescue of the exploding munition ship Florence H. off Quiberon Bay and together saving half her crew, as well as tangling with German submarines directly.

All three sisters survived the conflict and headed back home from “Over There” in early 1919, given orders to assemble at Philadelphia along with the rest of the older tin cans left on the Navy List.

“They did their bit” Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pennsylvania. Old destroyers in the Reserve Basin, 13 June 1919, while awaiting decommissioning. Note the truck and life rafts on the pier. These ships are (from left to right): USS Worden (Destroyer # 16); USS Barry (Destroyer # 2); USS Hull (Destroyer # 7); USS Hopkins (Destroyer # 6) probably; USS Bainbridge (Destroyer # 1); USS Stewart (Destroyer # 13); USS Paul Jones (Destroyer # 10); and USS Decatur (Destroyer # 5). Ships further to the right cannot be identified. Courtesy of Frank Jankowski, 1981. NH 92301

Worden was placed out of commission at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 13 July 1919– joining her two sisters who were likewise decommissioned earlier the same month– and all three stricken from the Naval Register on 15 September 1919.

Come, Mr. Tally Man…

3 January 1920, after just six months on red lead row, ex-USS Worden and her two sisters were sold cheap– pennies on the pound– to one Joseph G. Hitner, head of Philadelphia’s Henry A. Hitner’s Sons Ironworks. Now, Hitner was in the scrap business and had bought and recycled several ships from mothballs including 11 small Bainbridge-class destroyers, the old battleship Wisconsin (BB-9), the cruiser Raliegh (C-8), and the monitors Miantonomoh and Tonopah, but he hit on something different for the Truxtuns.

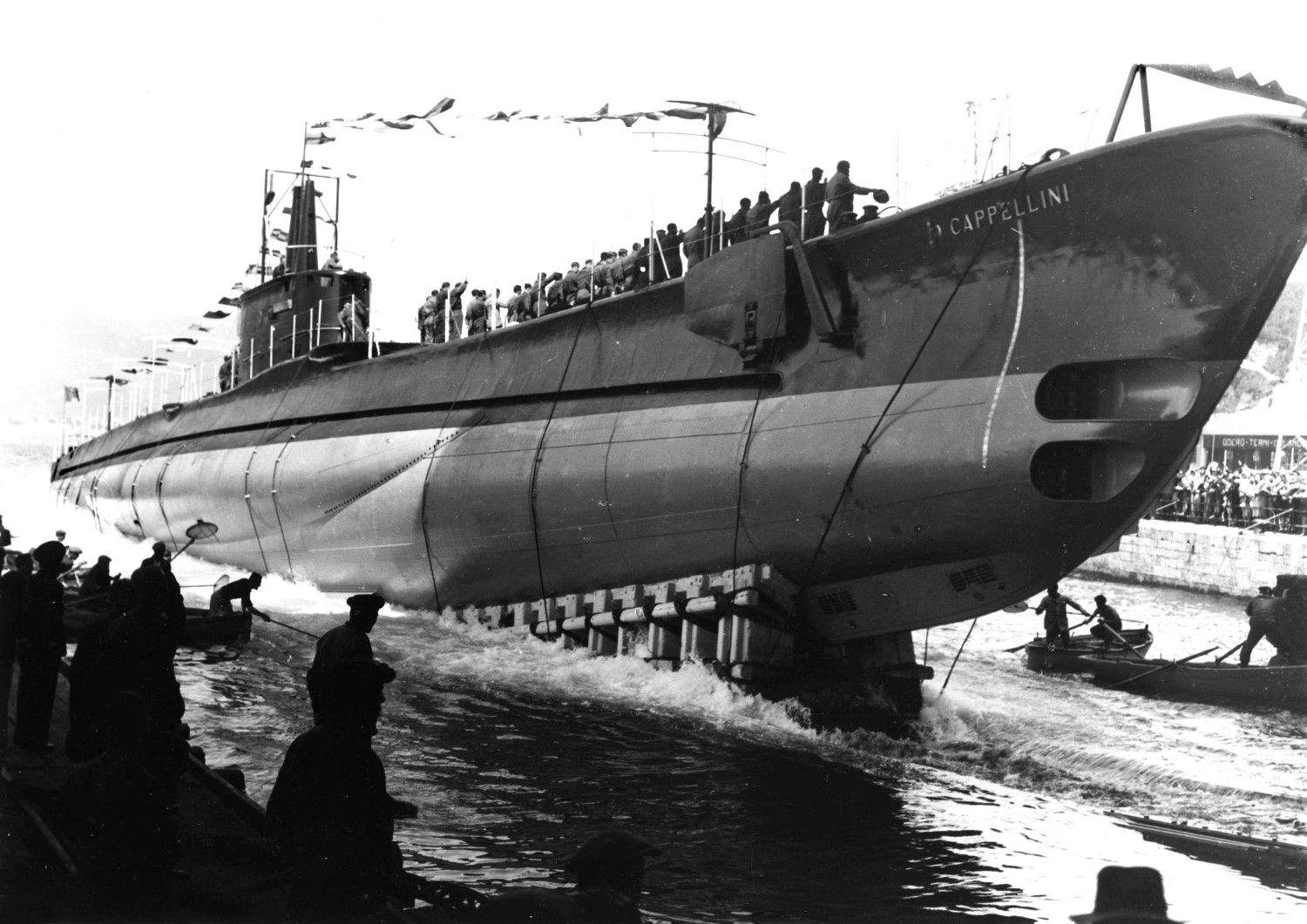

He decided to sell them for conversion to motor fruit carriers.

It made sense as the vessels were shallow enough to maneuver through the narrow fruit company waterways such as the Snyder Canal in Panama, and, with their engineering suite reduced and armament removed, were still fast and economical enough to get the job done. With their old magazines and one of their boiler rooms turned into banana holds, they could hold as many as 15,000 stems of fruit.

The ships were rebuilt, scrapping their old VTE suites and boilers for a pair of economical 12-cylinder Atlas Imperial Diesels– a company known for outfitting tugs and trawlers– generating 211 NHP and allowing a sustained speed of 15 knots. This removed all four of their coal funnels, replacing them with a number of tall cowl vents and a single diesel stack aft. So reconstructed, their weight was listed as 433 GRT with a 264-foot length and 14-foot depth of hold. The crew was reduced to an officer and 17 hands. Painted buff above the waterline to help reflect heat, they still had their greyhound lines.

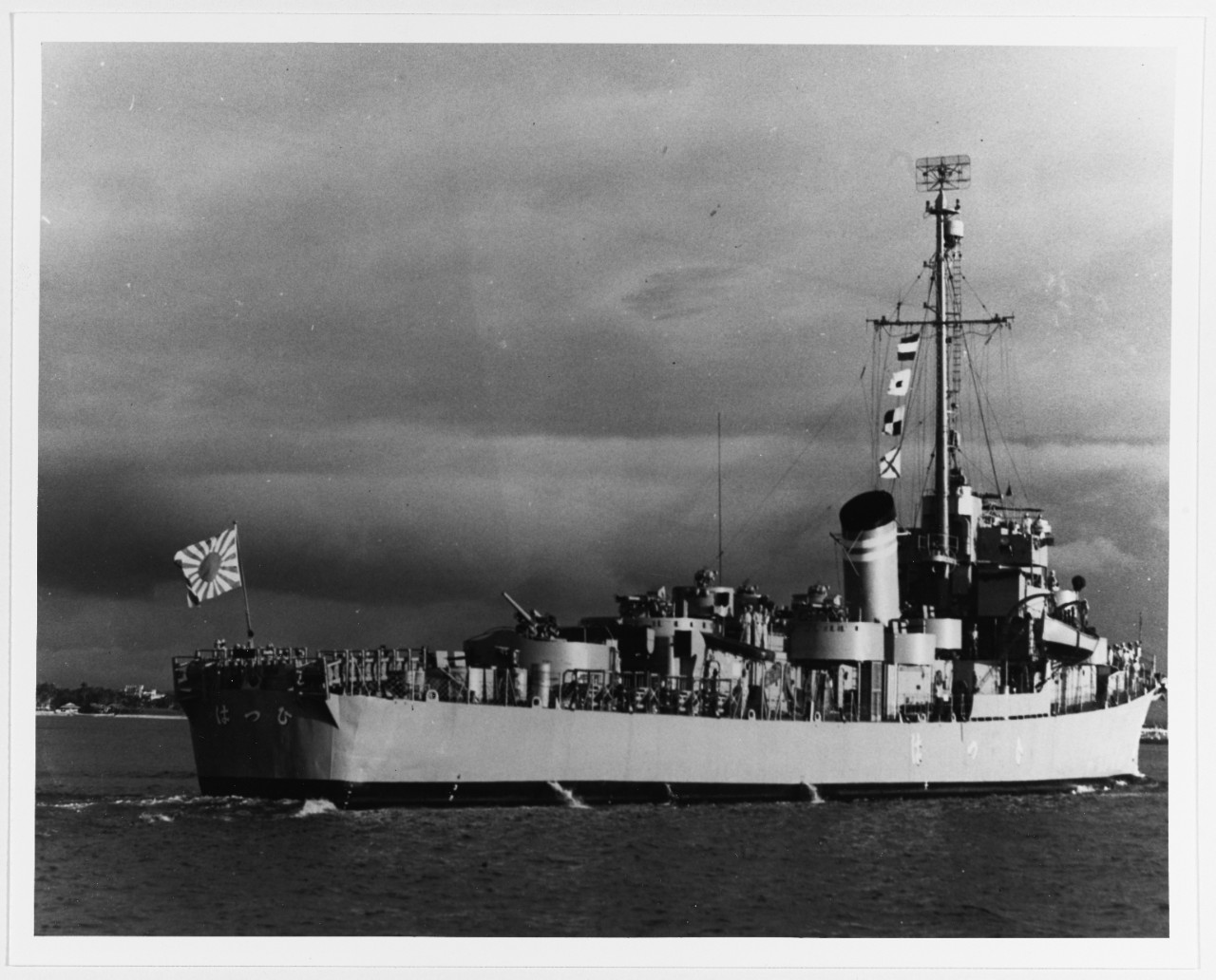

SS Truxton – the former USS Truxton (DD-14) after conversion to a banana boat

A Truxtun-class TBD/CTV recycled as a banana boat

The 1920s were part of the “Banana Boom,” an era that saw the importation of the Gros Michel AKA “Big Mike” variety of the fruit– now all but extinct– skyrocket. In 1872, just a half-century prior, only 300,000 bunches had reached American shores. By 1920, this jumped to 39 million. In 1928 alone, some 64 million bunches of bananas were exported to the U.S. from Caribbean countries, with Honduras and Jamaica supplying half of that total.

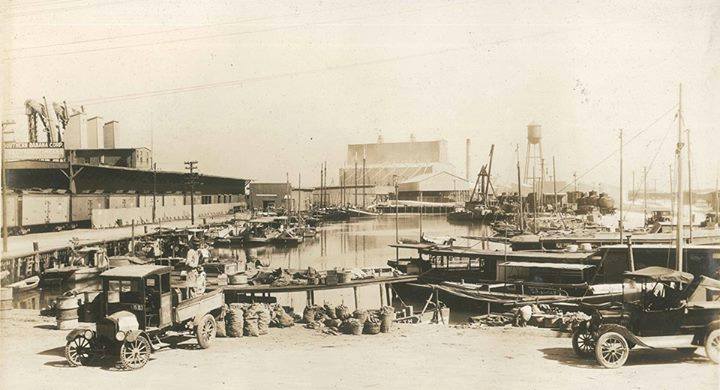

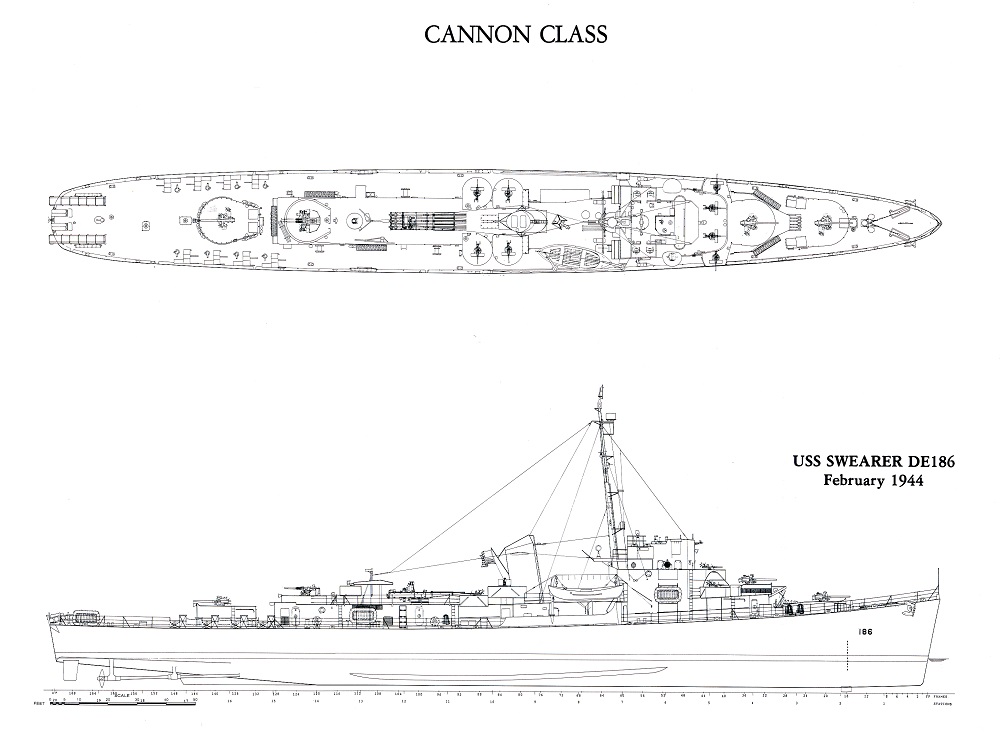

Southern Banana Company at Pier 19, Galveston 1920 via Galveston Historical Foundation

During the boom, over 20 companies were in the business of bringing the curved yellow fruit to the U.S., and Worden and her sisters would work for several of them.

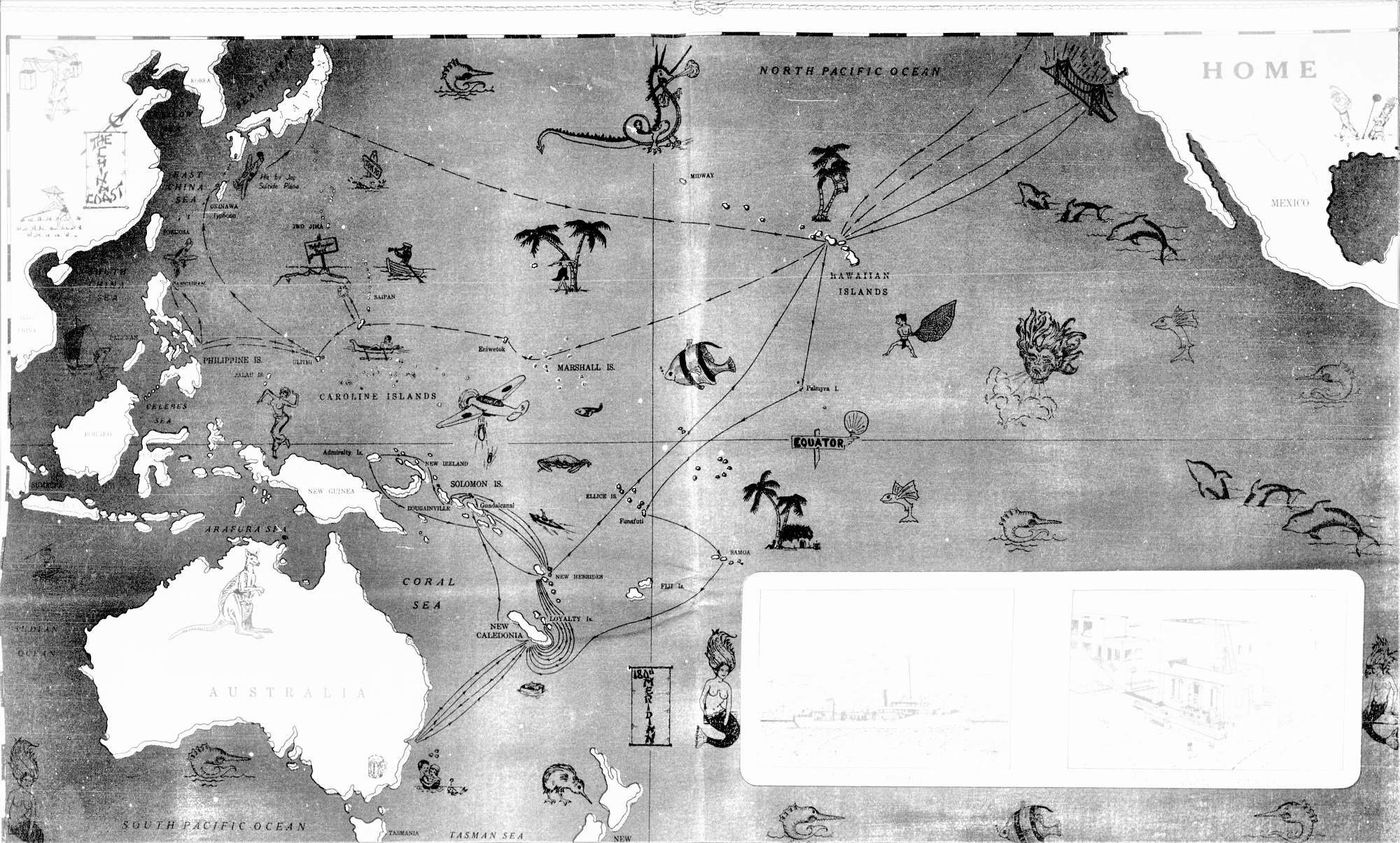

Worden along with her sisters Truxtun and Whipple was registered in 1921 by Robert Shepherd in Nicaragua and soon used on the banana runs to Galveston and New Orleans, flying the flag of the Snyder Banana Company of Bluefields.

In 1922, the boats had been impounded by R.A. Harvin, the United States Marshal in Texas, after a libel proceeding, and sold at public auction to one Harry Nevelson, who in turn quickly resold them to the Mexican-American Fruit Company, and sometime shortly after they were sailing for the Southern Banana Co.

By 1925, the trio was all part of the Vaccaro brothers’ upstart New Orleans-based Standard Fruit & S S Co (now part of Dole).

By 1933, Lloyds listed her as owned by the American Fruit & S S Corp — later adjusted to “Seaboard S S Corp (Standard Fruit, Mgrs)” in subsequent listings– out of Bluefields, Nicaragua with a tonnage of 546 GRT.

1933 Llyods

By 1939, the owners’ column had been lined out and she was listed as owned by the Bahamas Shipping Company and with tonnage adjusted to 433 GRT.

1940 Lloyd’s

Then came another war.

While Worden’s early war record is not available, her owners took great pain to try to make her as neutral as possible. This included a gleaming white livery with her Nicaraguan colors and name highlighted. She was under charter to the Winn-Lovett Grocery Company (now Winn-Dixie) to run bananas and assorted other fruits from Central America to Florida.

It was in this trade that Worden came across a fearsome sight some 80 years ago this month.

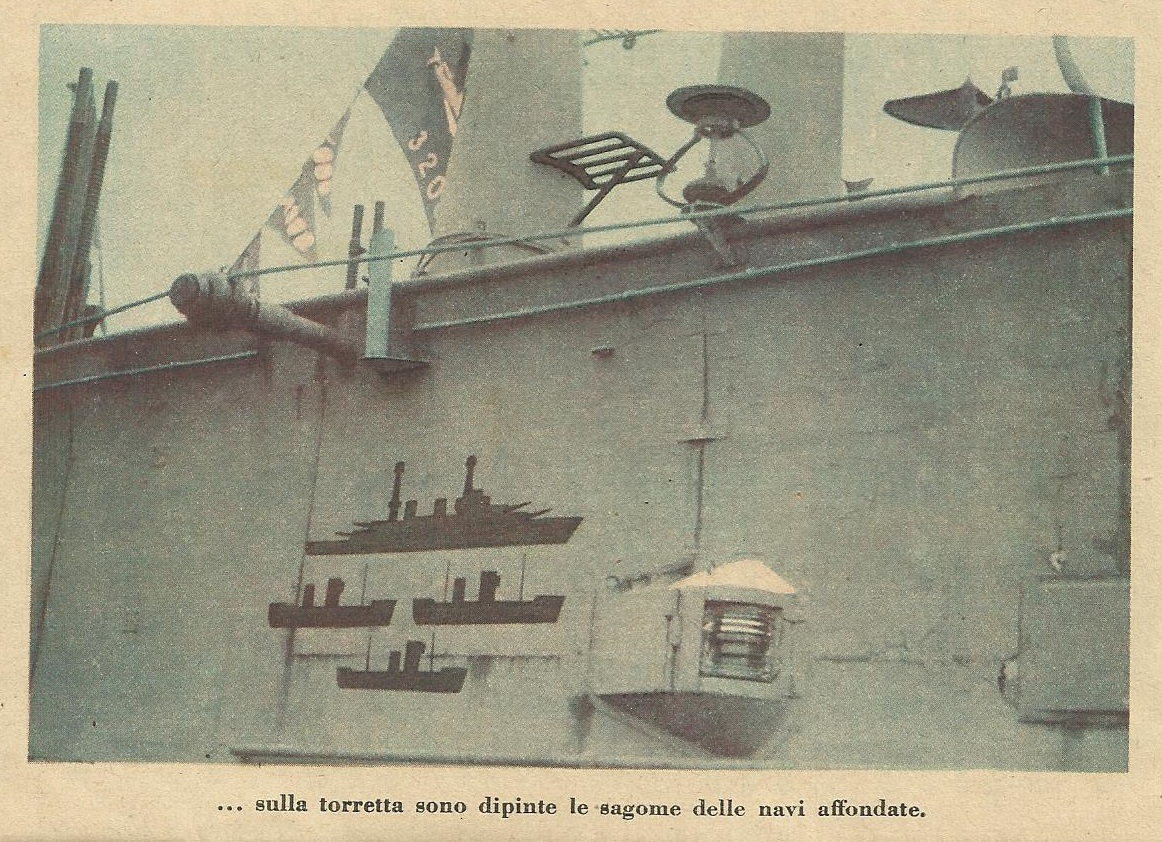

While about 10 miles southeast of Cape Canaveral, the 6,548-ton British-flagged freighter La Paz, carrying a mixed cargo of fertilizer, china, and several hundred cases of scotch from Liverpool to Valparaiso via Halifax and Hampton Roads, came across U-109, an experienced Type IXB U-boat, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Heinrich “Ajax” Bleichrodt. Sailing from Lorient under 2. Flottille on her 5th War Patrol, the German submarine had already chalked up a half-dozen Allied steamers in the previous year.

Firing two torpedoes, one of which hit the British steamship, La Paz‘s crew made for the lifeboats. Bleichrodt’s crew intercepted a radio message from the nearby Worden referencing the torpedoing as the U-boat was submerging and he apparently logged the latter down as his victim.

The torpedoed freighter, probably M.S. La Paz, off the east coast of Florida (80 10’W; 28 10′), 1 May 1942. Note the oil slick. Three lifeboats astern indicate that the ship is being abandoned. The Nicaraguan banana freighter Worden is standing by in the background. Official U.S. Navy Photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. Catalog #: 80-G-177164

The banana boat (ex-USN destroyer) Worden with her name, homeport (Bluefields, Nicaragua), and nationality (the Nicaraguan colors can be seen painted just behind her name) prominently displayed, takes the torpedoed British freighter, La Paz, in tow on 1 May 1942 off the Florida coast. U.S. Navy Photograph # 80-CF-1055.8B, Still Pictures Branch, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Md, caption via Navsource.

La Paz was beached seven miles off Cocoa, Florida, her flooded stern hard aground, and Worden went on her way. The wounded freighter was later towed to Jacksonville, repaired, and returned to service five months later under U.S. Maritime Commission control. In the meantime, Brevard County residents aided in the salvaging of the La Paz, hauling ashore some Johnny Walker for their efforts.

Via State Archives of Florida

As detailed by Bill Watts:

The decision to remove the La Paz’s cargo provided the young men of Cocoa the opportunity for one of their greatest wartime adventures—one that is still fondly recalled at almost every Mosquito Beaters’ meeting. The draft and war industries had depleted the supply of labor for the area, so the insurance representatives decided to hire boys from Cocoa High School to unload the cargo. It was hard work, but the boys went at it with a will. Soon, the china and most of the fertilizer were unloaded; then it was time to unload the scotch whiskey.

As Speedy Harrell tells the story, the boys were overawed by the large stacks of cases of whiskey, but they went to work. Sometime during the process of unloading some of the boys decided that nobody would miss a bottle or two, so they “liberated” a few bottles and buried them under the beach sand to be retrieved later. Eventually, according to Speedy, the bottles hidden under the sand became so numerous that it was impossible for anyone to walk on that area of the beach without causing a gentle clinking noise as the bottles banged into each other.

According to Röwer’s Axis Submarine Successes of World War II, U-109 sank Worden just after hitting La Paz. However, this is subject to much debate. Nautical historian Eric Wiberg says this came as a “result of confusion over radio transmissions. Worden was simply responding ‘in the clear’ via short wave radio to distress calls from La Paz.” Further, the photos circulating of Worden assisting La Paz belay the likelihood of her sinking at the same time and date. Notably, Uboat.net does not list Worden on U-109’s tally sheet.

Likewise, DANFS states plainly: “Although Bleichrodt claimed both ships as sunk, Worden with a torpedo meant for La Paz, both ships survived, La Paz salvaged and resuming service, the fruit carrier continuing in that trade into the post-war period.”

With that, though, while there seems to be no proof that Bleichrodt sent our plucky banana boat to the bottom, her final end is unknown.

In fact, she continued to show up in Lloyds throughout the 1940s and 1950s, eventually ending up under a Panamanian flag as part of the Consolidated Shipping Company in 1955. Not a bad run for a little torpedo boat destroyer.

Worden’s 1956 Lloyds Steamer listing

While listed by one source as broken up in 1956, I’d like to think her old hulk may be in some back river port in Central America somewhere, rusting quietly away on a sandbar as her deck offers shelter to shorebirds, reports of her demise greatly exaggerated.

Epilogue

Of Worden’s sisters, Truxtun was still in the banana trade in 1938 when she suffered an engine room fire off Haiti that left her a hulk there. Considered a total loss because of a lack of insurance to cover the cost of towing and repair, she was sold to Joseph Nadal and Company of Haiti and presumed scrapped.

Whipple, meanwhile, remained in the stables of the Nassau-based Bahama Shipping Co. alongside Worden into 1953, then dropped from the list shortly after, likely when BSC dissolved.

1949 Lloyd’s shipping biz listing for the Bahama SC, showing Whipple and Worden as their only vessels

Worden’s engineering drawings and plans are in the National Archives. Meanwhile, Tulane has several documents from her banana boat era.

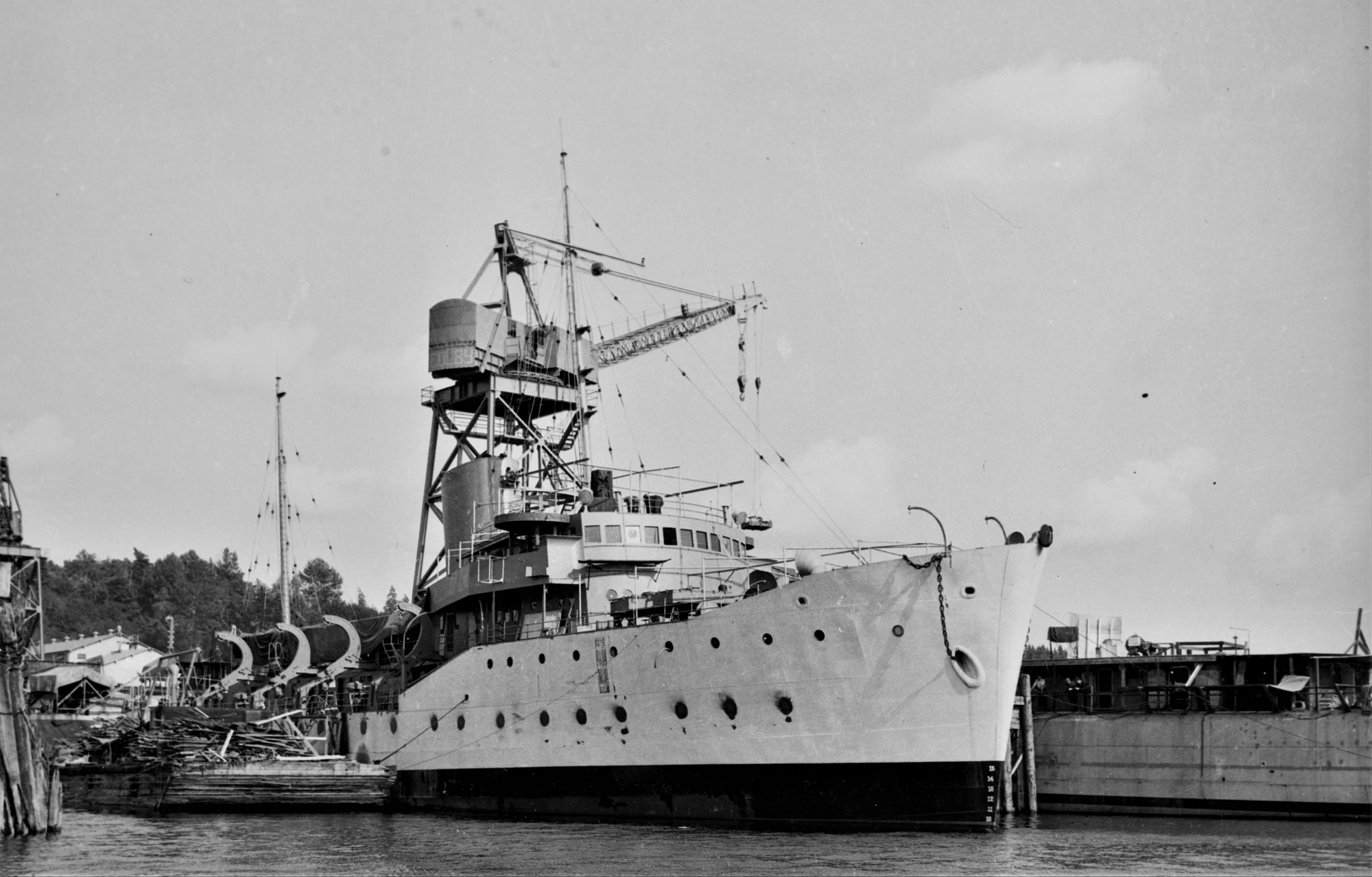

Besides our torpedo boat destroyer, the Navy has named three ships in honor of RADM Worden: the Clemson-class destroyer USS Worden (Destroyer # 288, later DD-288) which served from 1920-1931 (then ironically was also converted into the Standard Fruit Co. banana boat MV Tabasco and lost on a reef in the Gulf of Mexico in 1933); the Farragut-class destroyer USS Worden (DD-352) of 1935-1944; and the Leahy-class destroyer leader USS Worden (DLG-18, later CG-18) of 1963-2000.

A starboard bow view of the guided-missile cruiser USS WORDEN (CG 18) underway, 8/1/1987. DN-SC-89-08861. Via NARA.

It is time for a fifth Worden.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships, you should belong.

I am a member, so should you be!