Warship Wednesday, April 3, 2024: The Bathtub of Sampson, Schley, and Sims

Here at LSOZI, we take off every Wednesday for a look at the old steam/diesel navies of the 1833-1954 period and will profile a different ship each week. These ships have a life, a tale all their own, which sometimes takes them to the strangest places.- Christopher Eger

Warship Wednesday, April 3, 2024: The Bathtub of Sampson, Schley, and Sims

Above we see the “Propeller-class” brigantine-rigged cruising cutter Manning of the newly-formed U.S. Coast Guard as she steams in European service with the U.S. Navy during the Great War, circa 1917-18. Note her dazzle camouflage, rows of depth charges over her stern, and four 4″/50 cal open mounts, fore and aft, made all the more out of place due to her antiquated plow bow and downright stubby 205-foot overall length.

You wouldn’t know it to look at her, but Manning was in her second war and still had a lot of life left.

Turn of the Century Cutters

The Propeller class was emblematic of the Revenue Cutter Service– the forerunner of the USCG– at the cusp of the 20th Century. The USRCS decided in the 1890s to build five near-sisterships that would be classified in peacetime as cutters but would be capable modern naval auxiliary gunboats.

These vessels, to the same overall concept but each slightly different in design, were built to carry a bow-mounted torpedo tube for 15-inch Bliss-Whitehead type torpedoes (although they appeared to have not been fitted with the weapons) and as many as four modern quick-firing 3-inch guns (though they typically used just two 6-pounder, 57mm popguns in peacetime). They would be the first modern cutters equipped with electric generators, triple-expansion steam engines (with auxiliary sail rigs), steel (well, mostly steel) hulls with a navy-style plow bow, and able to cut the very fast (for the time) speed of 18-ish knots.

All were built 1896-98 at three different yards to speed up delivery.

These ships included:

–McCulloch, a barquentine-rigged, composite-hulled, 219-foot, 1,280-ton steamer ordered from William Cramp and Sons of Philadelphia for $196,000. She was the longest of the type as she was intended for Pacific service and so was designed with larger coal bunkers.

–Gresham, a brigantine-rigged 206-foot, 1,090-ton steel-hulled steamer built by the Globe Iron Works Company of Cleveland, OH for $147,800.

–Manning, a brigantine-rigged 205-foot, 1,150-ton steamer ordered from the Atlantic Works Company of East Boston, MA, for a cost of $159,951.

–Algonquin, brigantine-rigged 205.5-foot, 1,180-ton steel-hulled steamer ordered from the Globe Iron Works Company of Cleveland, OH for $193,000.

–Onondaga, brigantine-rigged 206-foot, 1,190-ton steel-hulled steamer ordered from the Globe Iron Works Company of Cleveland, OH for $193,800.

Meet Manning

As the USRSC (and the USCG until 1967) was part of the Treasury Department, our vessel was the only one named in honor of Grover Cleveland’s Treasury secretary, Daniel Manning, although she only carried the last name and not the full name while in service. Accepted by the Service, Manning was commissioned on 8 January 1898, and she would soon “see the elephant.”

War with Spain!

Unlike the coming World Wars where the entire Service would be placed under the control of the Navy, only those vessels deemed modern enough to hold their own in a fight were seconded to the larger sea-going branch for the conflict with the Empire of Spain.

On 24 March 1898, President McKinley instructed his T-Sec to place nine cutters– ours included– “under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, and cooperate with the Navy, until further orders. This was five weeks after the mysterious and controversial sinking of the USS Maine in Havanna harbor and a full month before Congress declared war on Spain, a fateful vote tallied on 25 April.

In all, the RCS would place 13 revenue cutters– carrying 61 guns and crewed by 98 officers and 562 enlisted— under Navy control during the conflict. This would include four (Grant, Corwin, Perry, and Rush) used to patrol the Pacific coastline and one (Manning’s sister McCulloch) to Commodore Dewey’s Asiatic Squadron for the push on Manila.

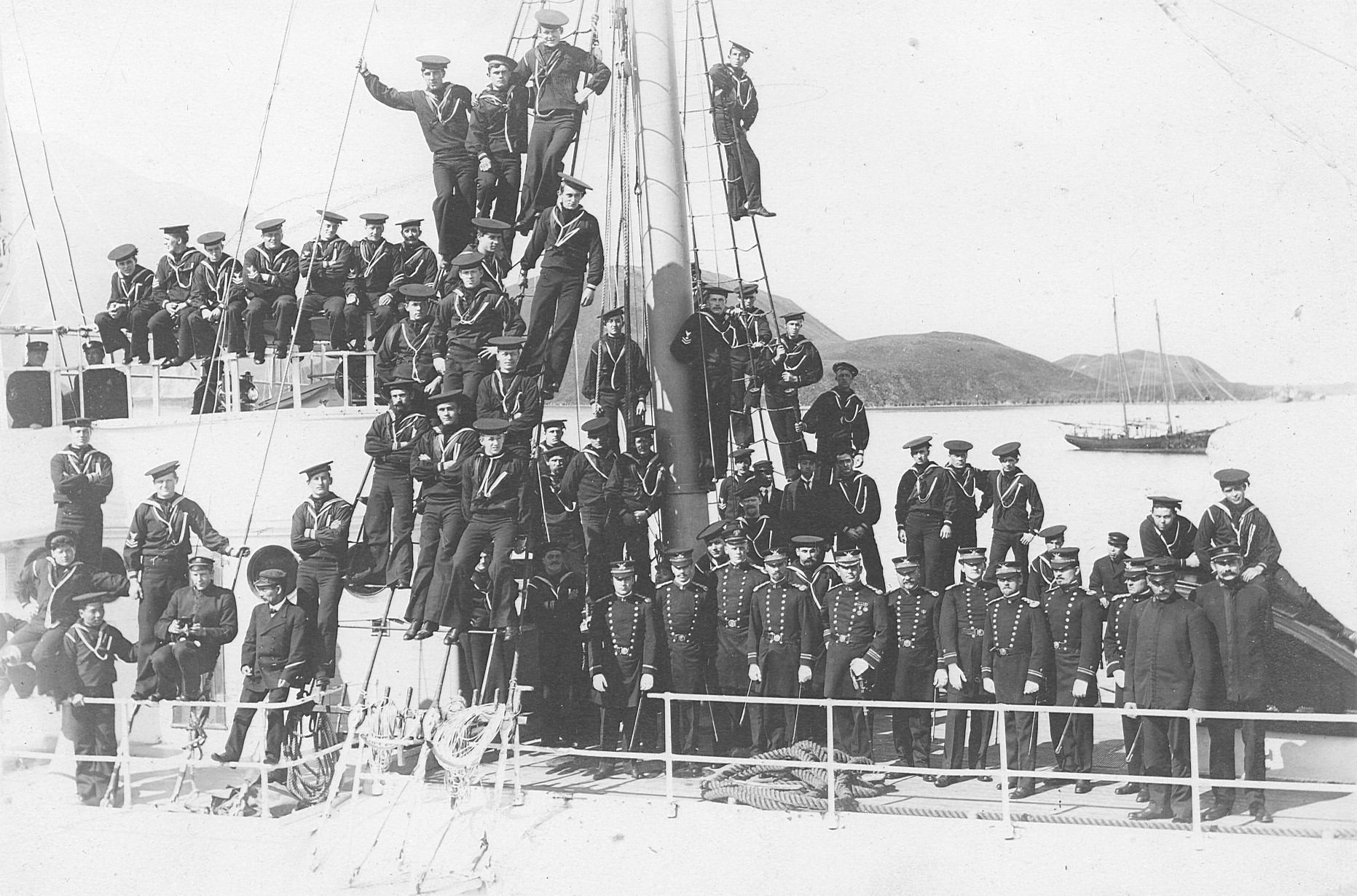

This left the Manning, under the command of Captain Fred M. Munger, Morrill, Hamilton, Windom, Woodbury, Hudson, Calumet, and McLane, to join the North Atlantic Squadron under RADM William Thomas Sampson (USNA 1861).

Meanwhile, another seven smaller cutters (Dallas, Dexter, Winona, Smith, Galveston, Guthrie, and Penrose), with a total of 10 guns between them and crewed by 33 officers and 163 men, were placed under Army orders patrolling coastwise minefields off protected harbors from Boston to New Orleans.

Manning was up-armed with three 4-inch guns (2 forward, one aft) with a mix of 250 AP and Common shells. She was also given steel gun shields for her 6-pounders for which she took on 1,500 AP shells, and was fitted with a Maxim-Nordenfeldt 1-pounder 37mm “pom pom” with another 2,200 rounds for that eclectic gun.

A Maxim-Nordenfelt 37mm 1-pounder autocannon fitted on the yacht USS Vixen in 1898. Manning was fitted with one of these for her SpanAm War service. Basically a super-sized Maxim machine gun, it had a very respectable 300 rpm rate of fire, as long as the shells held out. LC-DIG-det-4a14810

Manning would head south to Key West, and eventually be folded into Commodore Winfield Scott Schley’s 2nd Squadron.

His little gunboat was listed by the Navy as having engaged in combat on 12 and 13 May at Cabanas and Mariel, Cuba, and 18 July at Naguerro. Munger noted some 71 rounds of 4-inch and 148 rounds of 6 pdr. ammunition expended in the earlier of the three.

May 12, 1898, USS Manning in engaged off Cabanas, Cuba By Lieut. G. L. Carden, R.C.S. This is the only known photo of a Revenue Cutter in action during the Spanish-American War.

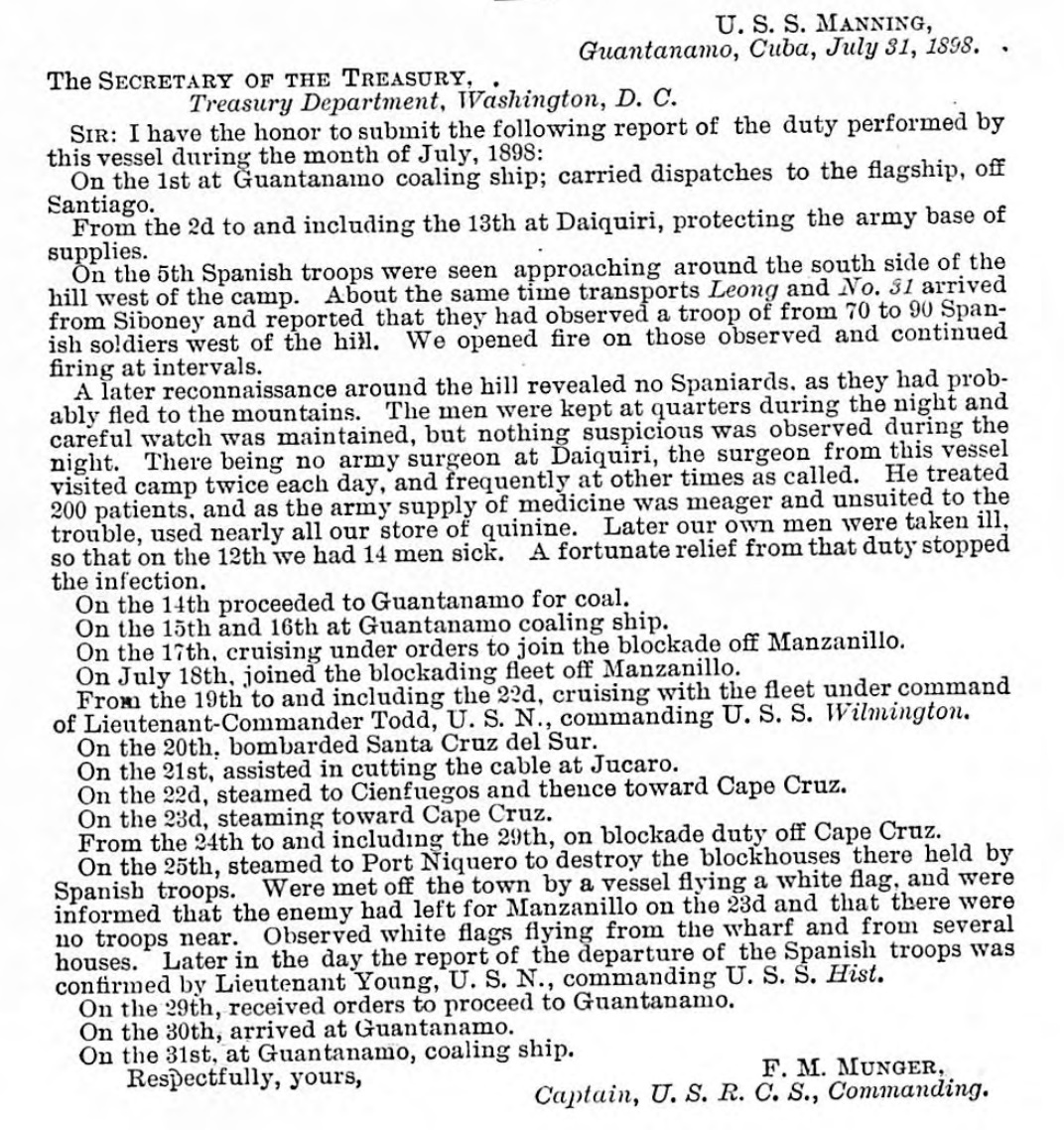

Munger filed three detailed reports with the T-Sec’s office, detailing the cutter’s actions in the war, including a total of some 600 rounds fired across several more engagements than what the Navy detailed.

Returned from Navy service to the RCS on 17 August 1898, Manning put into Norfolk to remove the bulk of her wartime armament and settled into her “salad days.”

Interbellum

USRC Manning. Photograph by Hart, taken off New York City circa 1898-99. Note that she still has at least one 4-inch gun forward and her steel shields over her 6-pounders. NH 46627

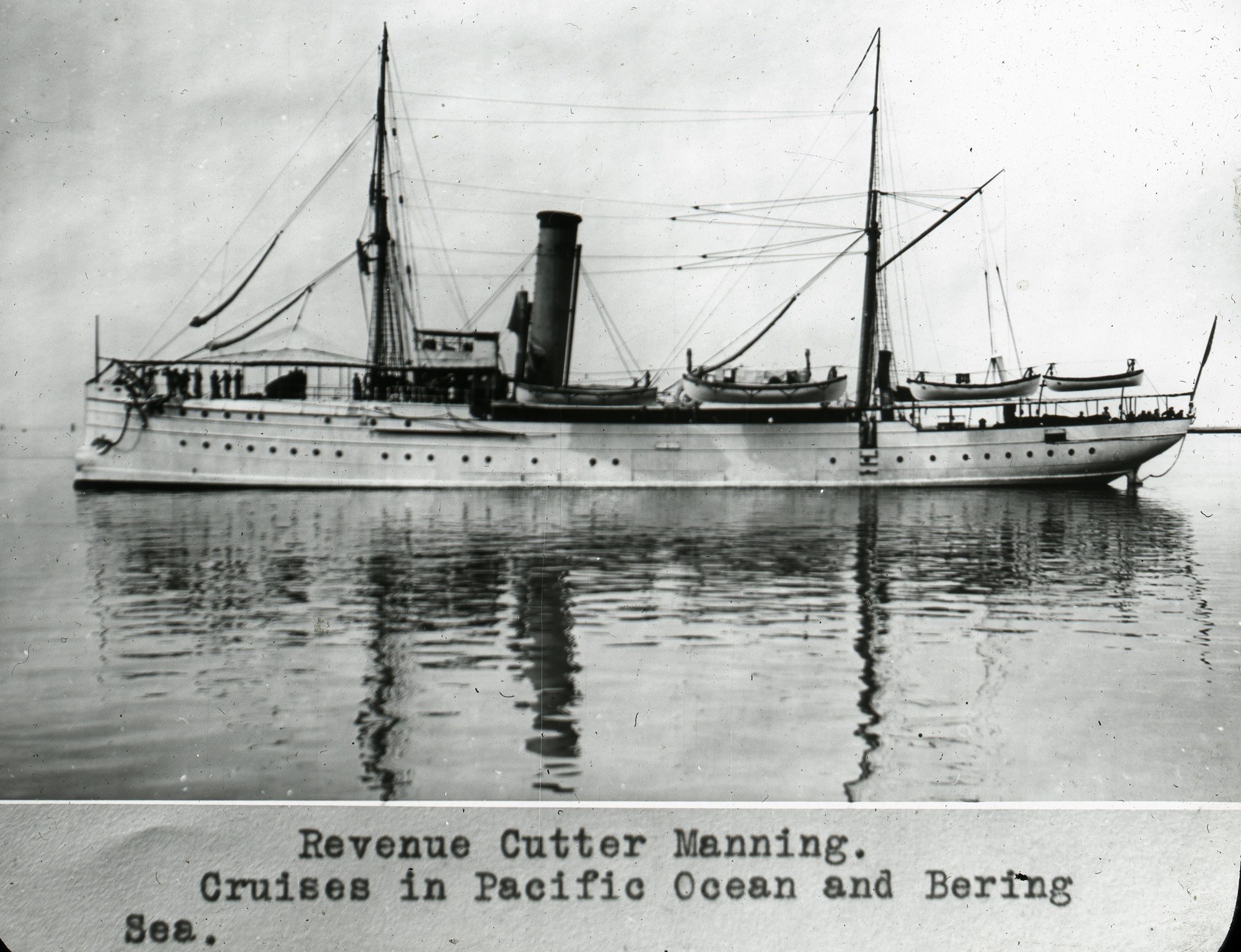

On 2 January 1900, Manning was ordered to report to San Francisco via the Straits of Magellan for duties with the Bering Sea Patrol, where she would perform the hard work in the remote region for 13 of the next 16 summers, with occasional pivots to warmer climes in Hawaii.

As with other cutters sent to Alaska, this ranged from policing fishing and sealing grounds, responding to natural disasters, conducting hydrographic surveys, responding to wrecks and distress, and generally serving as the sole federal institution for hundreds of miles in many cases– a job that spanned from carrying supplies and medicine to isolated coastal villages to serving as constabulary force ashore, and even holding court with an embarked judge from time to time. Her Public Health Service physician was often the only medical professional to call at many of these areas with any regularity.

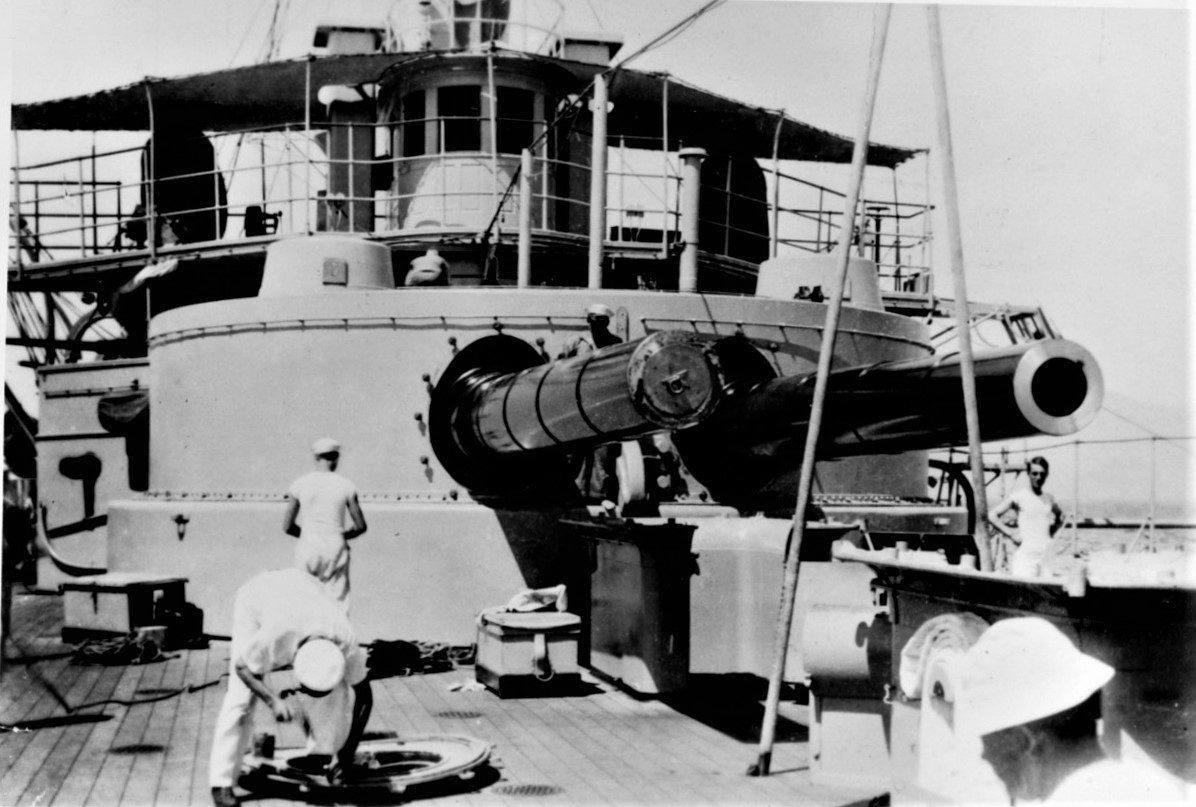

U.S. Revenue Cutter Manning, Unalaska, Aug. 1908. A great view of her torpedo tube. LOC LC-USZ62-130291

Equipped sometime during this period with a 2-KW DeForest spark transmitter/receiver, Mannng could also serve as a floating wireless station while her original coal-fired suite was replaced with oil-fired boilers during a refit at Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

At Sea – “USRC Manning’s race boat crew (1902-1904) which used the Corwin’s Gig. Left to right: Seaman ‘Frenchie’ Martinesen, Master-at-Arms Stranberg (Coxswain), Seaman Andreas Rynberg, Magnus Jensen, and Franze Rynberg.”

Japanese schooners caught poaching near the Pribilof Islands, Bering Sea, Alaska, 1907. “On verso of image: Schr. Nitto Maru is in the foreground. Schr. Kaiwo Tokiyo in the center. Both poachers on Pribloff Islands, Behring Sea, now under the guard of Rev. Cutter McCulloch at Unalaska. Manning is on the right. 63 Japanese in both crews.” John N. Cobb Photograph Collection, University of Washington UW14289. At the time, Capt. Fred Munger, Manning’s old SpanAm War skipper, was head of the Bearing Sea Fleet.

Manning, 1912. Note this is before her refit that changed her to oil and reduced her masts, ditching her auxiliary sail rig. Note her torpedo tube, still with a hatch.

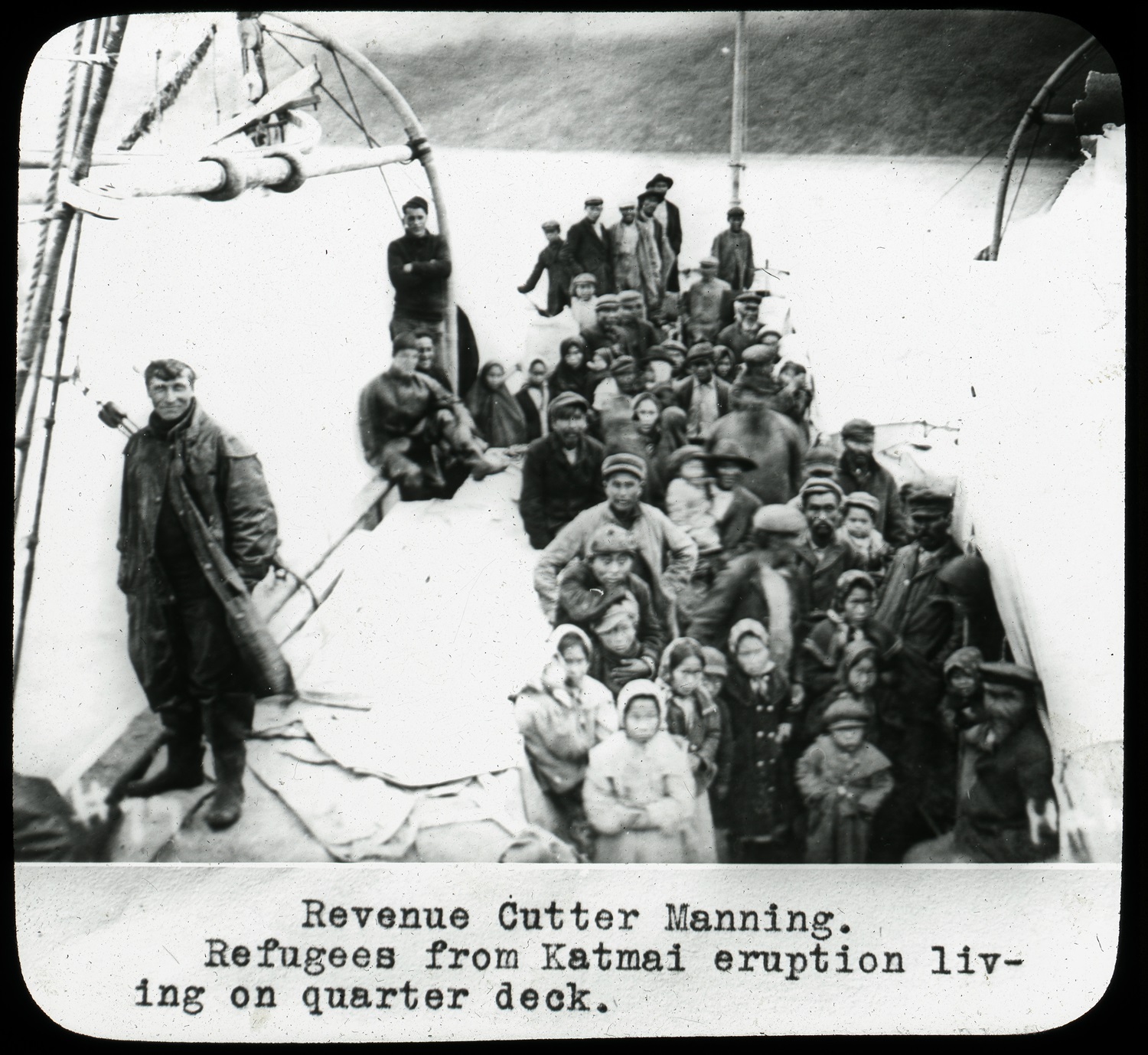

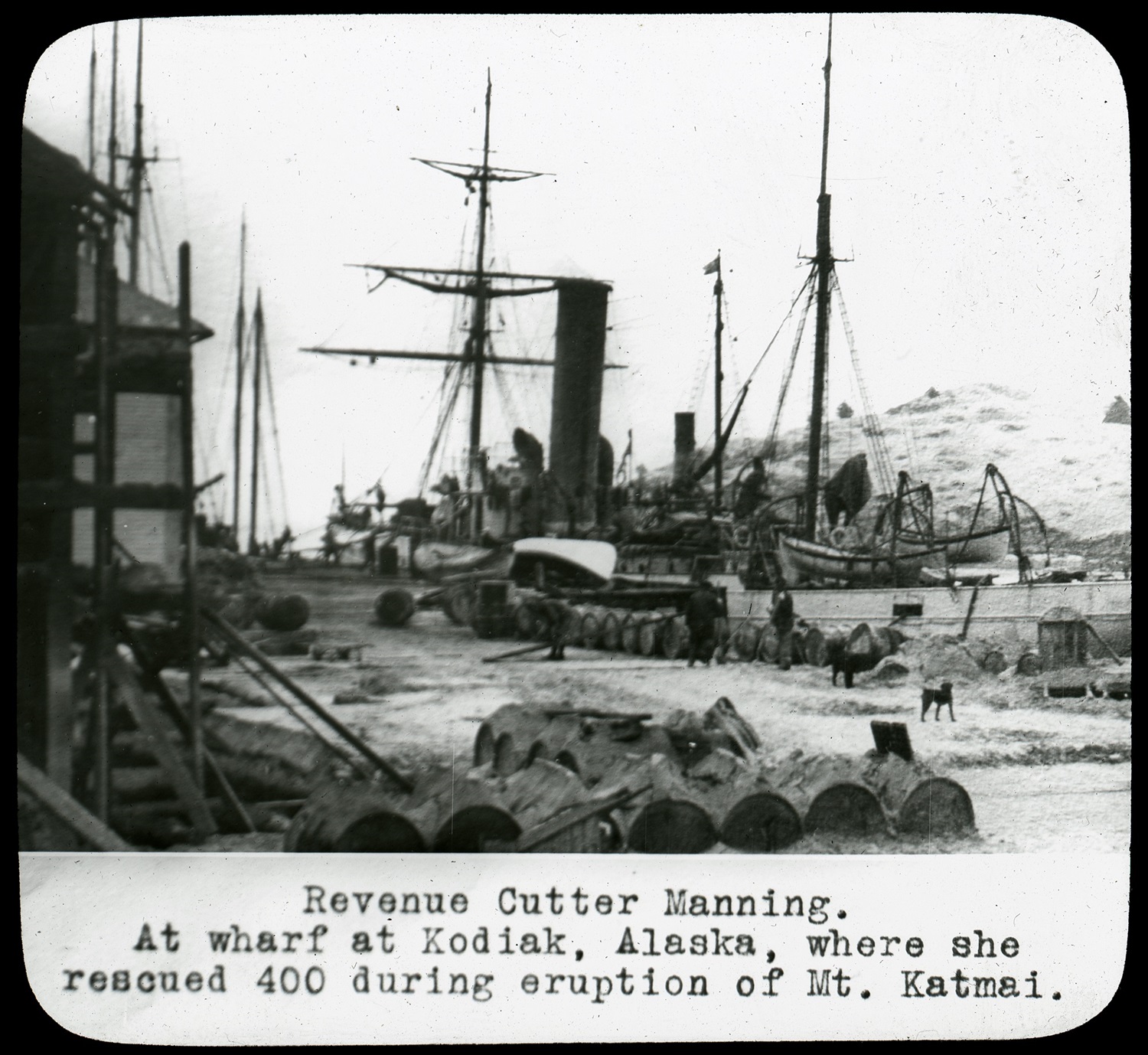

In June 1912, while docked at Kodiak Island, Manning’s crew noted the rumbling and ash in the distance that was the historic eruption of Novarupta/Katmai— the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th century. She would spend the next several days harboring refugees from the surrounding communities– as many as 414 onboard the small gunboat at any one time– and, as every well was full of ash, run her then rare desalination plant to make fresh water.

Crew and deck of the US Revenue Cutter Manning covered in ash from June 6, 1912. Via Anchorage Museum

U.S. Revenue Service cutter Manning, crowded with Kodiak residents seeking safety during the 1912 eruption of Novarupta, which resulted in about a foot of ashfall on Kodiak over nearly three days. The photograph was published in Griggs, 1922, and was taken by J.F. Hahn, U.S.R.S.

While many of her crew became sick from the ash of Navarupta, and she had fought both malaria and the Spanish off Cuba for nearly four months during the war, Manning had been a lucky ship when it came to deaths. This streak ended on 10 October 1914 when she lost four crewmen and a Public Health Service physician after one of her small boats swamped in heavy surf off Sarichef, Unimak.

Then came trouble in Europe.

Great War

While in Astoria, Oregon on 26 January 1917, Manning received orders to report, via the Panama Canal, to the Coast Guard Depot at Curtis Bay, Maryland to prepare for possible Naval service.

Soon after she arrived there, on 6 April 1917, the day Congress declared war on Imperial Germany, U.S. Navy’s radio centers transmitted “Plan One, Acknowledge” to all Coast Guard cutters, units, and bases, the code words initiating the service’s transfer from the Treasury Department to the Navy and placing it on an immediate wartime footing. Manning became part of the Navy once again.

It was decided to use the little gunboat as part of the scrappy Squadron 2, Division 6 of the Atlantic Fleet Patrol Forces, and sent overseas to report to VADM(T) William Sowden Sims. Based at Gibraltar, this force consisted of six Coast Guard cutters (Tampa, Algonquin, Seneca, Manning, Ossipee, and Yamacraw). On a list compiled for the British Admiralty, the USCG cutters were described as “good sea boats, good crews, much better than old gunboats.”

With Royal Navy communications personnel aboard, they would escort convoys between Gibraltar and the British Isles and conduct antisubmarine patrols in the Mediterranean against very active German U-boats there.

For her role, Manning and her sister cutters headed to Gibraltar were given a dazzle camouflage scheme. She and sister Algonquin would be armed with four 4-inch guns with 1,500 shells stored in two magazines fore and aft, two racks capable of carrying 16 300-pound depth charges, and four 30.06 Colt “potato digger” machine guns. A small arms locker would be filled with a pair of .30-06 Lewis guns, 18 .45 caliber Colt pistols, and 15 Springfield rifles.

Although Manning’s Gibraltar service is not well documented, the risk was no joke as fellow Squadron 2 cutter Tampa, after completing a convoy run from Gibraltar to England, was torpedoed by UB-91, killing all 131 (111 USCG, 16 RN and 4 USN) personnel aboard.

Returning to USCG service

Reverting back to the Treasury Department on 28 August 1919, Manning would remain on the East Coast, spending the next 11 years operating out of Norfolk with her traditional white hull. During this period, she would participate in the reestablished International Ice Patrol, and take part in the “Rum War” against bootleggers, and other traditional USCG taskings.

U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Manning At Norfolk, Virginia, 30 December 1920. Note her armament has been landed but her torpedo tube remains although the hatch has been removed and the tube plated over. Panoramic photograph, taken by Crosby, Boston, Massachusetts. Donation of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum, 1970. NH 105313

Manning would be involved in the landmark human smuggling case of the schooner Sunbeam in December 1919 and race to the scene of the sinking British liner SS Vestris off the Virginia Capes in November 1928.

Manning, Norfolk, 1920s. Note the lattice masts of the battleship to the right and the tall gantry works of what looks to be a Proteus class collier to the right

Manning late in her career. Note her RF DF equipment. Also, her torpedo tube has been removed altogether.

Past her prime and slated to be replaced by a new and much more modern 250-foot Lake class cutter, Manning was decommissioned at Norfolk on 22 May 1930. The following December, she was sold to one Charles L. Jording of Baltimore for just $2,200.02.

As for her classmates: Cleveland-built sisters Algonquin and Onondaga had been sold in 1930 and 1924 respectively and disposed of. Gresham, sold by the Coast Guard in 1935 for scrap was required by the service in WWII for coastal patrol, then became part of the Israeli Navy before disappearing again in the 1950s and was last semi-reliably seen in the Chesapeake Bay area as late as 1980. McCulloch was lost in 1917 northwest of Point Conception, California when she collided with the Pacific Steamship Company’s steamer Governor (5,474 tons) in dense fog and endures as a reef.

Epilogue

Some of her logs are digitized and online. Few other relics of the old girl exist, which is a shame.

While the Coast Guard has not commissioned a second USCGC Manning, it did, in 2020, commission a painting by Michael Daley, MBE, GAvA, of the old girl steaming out of Gibraltar at the head of a convoy during the Great War with another cutter on the horizon.

Artist Michael Daley, MBE, GAvA. CGC MANNING escorting a convoy out of Gibraltar during World War I. 210610-G-G0000-101

Ships are more than steel

and wood

And heart of burning coal,

For those who sail upon

them know

That some ships have a

soul.

If you liked this column, please consider joining the International Naval Research Organization (INRO), Publishers of Warship International

They are possibly one of the best sources of naval study, images, and fellowship you can find. http://www.warship.org/membership.htm

The International Naval Research Organization is a non-profit corporation dedicated to the encouragement of the study of naval vessels and their histories, principally in the era of iron and steel warships (about 1860 to date). Its purpose is to provide information and a means of contact for those interested in warships.

With more than 50 years of scholarship, Warship International, the written tome of the INRO has published hundreds of articles, most of which are unique in their sweep and subject.

PRINT still has its place. If you LOVE warships you should belong.

I’m a member, so should you be!